5 June 1619 and the ‘Kaiserliche Armee’

The ‘Kaiserliche Armee’ (Emperor’s army) was a name that stuck to the Habsburg forces until their dissolution in 1918. It was a title fashioned in the extraordinary crisis of June 1619. Before that moment no one had thought of the Habsburgs’ troops as the personal property of the sovereign. A few dramatic moments changed all that and thenceforth a bond was formed between soldier and monarch which endured for three centuries. The strength of this new relationship was quickly tested in the Thirty Years War. When that conflict threw up in the shape of Wallenstein the greatest warlord of his time, the issue of loyalty became critical. The dynasty was eventually able to rely on its soldiers to eliminate the threat. By the end of this period the Kaiserliche Armee was an undisputed reality.

The first week of June takes Vienna in a haze of heat and dust. Throats become parched as the warm wind raises small clouds of dirt along roads and tracks. The Viennese, irritable at the best of times, fractiously push each other and the stranger aside, addictively and automatically seeking shade and shelter. While the clouds become darker the stifling humidity immobilises even the pigeons, which gather dozily on the surfaces of the dusty courtyards of the Hofburg, the Imperial palace whose apartments were, are and always shall be synonomous with the House of Habsburg.

In June 1619, Vienna had not yet reached its unchallenged position as capital of a great European empire. True, the Habsburgs had come a long way since 1218, when a modest count by the name of Rudolf had brought the family out of the narrow Swiss valleys of his birth and, through a series of battles and later dazzling dynastic marriages, had propelled a family of obscure inbred Alpine nonentities into the cockpit of Europe whence they would become the greatest Imperial dynasty in history. Other countries might have many families over the years to supply their monarchs – the case of England leaps to mind – but the story of Austria and the heart of Europe is really the story of one, and only one, family: the Habsburgs.

By the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Habsburgs as a world power were already past their zenith. The Empire ‘on which the sun never set’, with its domains across Spain, Latin America and Germany, had split into two on the retirement of Charles V in 1556. The Spanish domains had gone to Charles’s son Philip II while the Austrian domains enmeshed with the fabric of the Holy Roman Empire had passed to Charles’s nephew Ferdinand. Even England in 1554 when Philip married Queen Mary at Winchester Cathedral had seemed destined to be incorporated permanently into this family’s system.

But while the Spanish domains were a more cohesive entity, the Austrian branch, assuming its ‘historic’ right to the crown of Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire, was a rich tapestry of principalities, Lilliput kingdoms and minor dukedoms in which different races owed their allegiance to the Holy Roman Emperor. The title was not hereditary, however much the Habsburgs may have thought it their own. The Emperor was elected by a council of seven princes who gathered at Frankfurt am Main. The Habsburg claim to this title, which from 6 January 1453 they perceived as almost a family right, arose from the possession of their crown lands in Central Europe and above all their title to the Kingdom of Bohemia. Although the Austrian Habsburgs could never really aspire to the global status their family had achieved under Charles V a generation earlier, they were to assume a powerful position in European history.

A half-century after the great division of Charles’s Habsburg spoils, Vienna still had rivals. Graz to the south and east and Prague to the west and north were both cities of importance to the Habsburgs. In the latter Rudolf II, philosopher, astrologer and occultist, had set up his capital in 1583, tolerating the ‘new’ Reformation theologies. In the former, the Archduke Ferdinand after his childhood in Spain and a Jesuit education in Bavaria had ruled the Styrian lands of ‘Inner Austria’ in a different manner. Between these two very different poles of authority Vienna still had not yet come of age. But in the hot days of June 1619, Vienna was to establish now an unrivalled ascendancy, becoming for a few moments the fulcrum of a pivotal conflict.

On 5 June, as the soporific wind carried the dust across the Hofburg palace towards the great Renaissance black and red ‘Swiss Gate’, a heated exchange could be heard through the open shutters of the dark masonry above. A sullen and armed mob numbering about a hundred had gathered below to await the outcome of this exchange, intimidating the guards and cursing the name of Habsburg.

In the dark vaulted rooms above the Schweizer Tor the object of all this hostility sat at his desk, facing the mob’s leaders, his frame defiant; his expression inscrutable. Diminutive in stature and stiff in countenance Archduke Ferdinand of Graz seemed unequal to the men who, unannounced, had burst into his rooms. These men were tall and rough; their hands large, bony and unmanicured. Their faces were twisted into angry and threatening expressions and the virtue of patience, if they had ever experienced it, was not uppermost in their minds.

They were a gang of Protestant noblemen who had defenestrated two of Ferdinand’s representatives, Slawata and Martinic, from the great window of the Hradčany castle in Prague barely a year before, initiating the violent challenge to Habsburg authority which became the Thirty Years War. Their leader, Mathias Thurn, was a giant of a man who had used the pommel of his sword to smash the knuckles of his victims as they held on for dear life to the ledge of the window. That both men had cried for divine intervention and – mirabile dictu – had fallen safely on to dung heaps had not in any way been due to Thurn’s going easy on them. Moderation was not his strongest suit. And now on this stifling day in Vienna, Thurn was again in no mood for negotiation. His large-boned fists crashed down on the desk in front of him. He may have been Bohemia’s premier aristocrat but he was passionate, hot-headed and violent.

Martin Luther’s ‘Reformation’ a hundred years earlier with its challenging practicalities, rejection of Papal corruption, increasing anti-Semitism and radical challenge to the authority of Rome had spread its tentacles across Germany into Bohemia and the new faith had fired the truculence and latent Hussite sympathies of the Bohemian nobility. Two hundred years earlier Jan Hus, the renegade Czech priest, had roused the Bohemians to revolt and he had been burned at the stake in Prague for heresy against the Catholic Church. Now, under Thurn, Hus’s legacy of a Bohemian challenge to Catholic Habsburg authority had been reinvigorated with all the pent-up energy of the ‘Reformation’. These sparks were literally about to set Europe ablaze.

Ferdinand of Graz

Ferdinand was a pupil of the Jesuits, one of the new orders established in 1540 by the Vatican to combat heresy and invigorate the Church. In 1595, at the age of 18, he had arrived in ‘Reformation’ Graz on Easter Sunday. When he celebrated Mass in the old faith that day, inviting the population to join him, he was dismayed to find that not a single burgher of Graz appeared. Styria at the end of the sixteenth century was overwhelmingly Protestant. Ferdinand with all the dignity of his upbringing showed no outward sign of disappointment but he immediately set about radically changing this state of affairs.

His Spanish upbringing and his devotion to the Jesuits could only produce one practical result. There were to be no half-measures. Ferdinand publicly proclaimed that he would rather live for the rest of his life in a hair shirt and see his lands burned to a cinder than tolerate heresy for a single day. Within eighteen months, Protestantism ceased to exist in Styria; every Protestant (and there were tens of thousands of them) was either converted or expelled, among the latter the great astronomer Kepler, who travelled to Prague. Every Protestant text and heretical tract was burned, every Protestant place of worship closed. Two weeks was allowed to the population to choose exile or conversion. As an exercise in largely bloodless coercion Ferdinand’s measures have no equal. The Styrian nobility capitulated. When during the following Easters, Ferdinand celebrated Mass, the entire population of the city turned out to join him. To this day, as Seton-Watson, the historian of the Czechs and the Slovaks, observed, there is ‘no more dramatic transformation in the history of Europe than the recovery of Austria for the Catholic Faith’.

But in 1619 Vienna was not Graz and the Bohemian nobility with their Upper Austrian supporters were not to prove as pliant as their Styrian counterparts. On 5 June 1619, Ferdinand, now 41 years of age, might have been forgiven for believing his Lord had deserted him. Inside the palace, Ferdinand’s supporters appeared demoralised and despondent. Ferdinand and his Jesuit confessor alone remained calm. For several hours, as they had awaited Thurn, the Archduke had prostrated himself before the cross. It seemed a futile gesture. The rest of Europe had already written Ferdinand off. France, the leading Catholic power, had withdrawn any offer of help. In Brussels, in the Habsburg Lowlands, members of Ferdinand’s family spoke of replacing the ‘Jesuitical soul’ with the Archduke Albert, a man altogether less in thrall to the vigour of the gathering forces of the Counter-Reformation. Even Hungary, of which, like Bohemia, Ferdinand was theoretically King, appeared to be on the brink of open rebellion.

Ferdinand had abandoned his ill and dying son to hurry to Vienna from Graz towards the end of April in 1619 to meet the emergency in Bohemia head-on and rally the Lower Austrian nobility. But in the seven dry and hot weeks of the spring of 1619 his journey had been less of a pageant and more of a via dolorosa. Everywhere he had encountered refugees from Bohemia and Moravia where, following the defenestration, the rebels had seized church property. Many were monks and nuns from plundered churches and convents. The Catholics, hunted out of Upper Austria, fell to their knees as their Emperor passed but few imagined this slight man could save them from the perils of their time. When Ferdinand reached Vienna at the end of May 1619, the hot weather had contributed to another pestilence to add to heresy: the plague.

As the Bohemian rebels, Starhemberg, Thurn and Thonradel smashed their way into the Hofburg they could be confident that all the strong cards were in their hands. How could this little Archduke hope to resist their demands? They would intimidate him and force him to sign documents that would restore their freedom to worship in the new faith, confirm their privileges and above all compel the hated Jesuits to leave the Habsburg crown lands of Styria and Bohemia. If he resisted, well the windows were large and high enough in the Hofburg and, as Thurn must have noticed with satisfaction as he raced up the stairs of the Schweizer Tor, there was no dung heap here to cushion a fall.

For what seemed might be the last time the Habsburg withdrew to his private oratory, and once again prostrate in front of the cross Ferdinand quietly prayed that he was ‘now ready if necessary to die for the only true cause’. But, Ferdinand added, ‘if it were God’s will that he should live then let God grant him one mercy: troops’, and, he added as the noise rose without, ‘as soon as possible’.

As the Bohemian ringleaders burst into Ferdinand’s rooms, one of their number, Thonradel, seized the collar of Ferdinand’s doublet. According to one account, Thonradel forced the Archduke to sit down at his desk. Taking a list of their demands out of his own doublet, the rebel placed them on the desk in front of the Archduke and screamed in Latin: ‘Scribet Fernandus!’

What would have happened next had these men remained undisturbed and allowed to continue this rather one-sided dialogue will never be known for at precisely this moment the sound of horses’ hooves and the cracked notes of a distant cavalry trumpeter brought the confrontation to an abrupt halt.

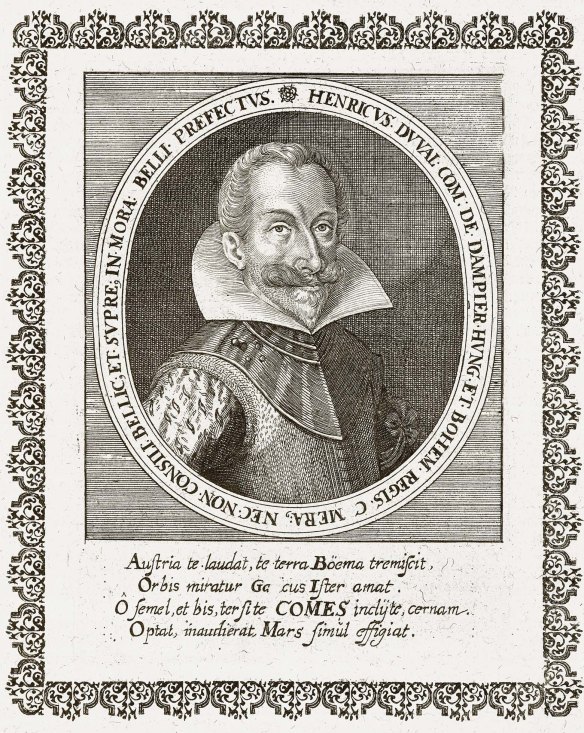

As the clatter of horsemen wheeling below brought both the Archduke and his persecutors to the window, no one was arguably more surprised than Ferdinand. Below, to the consternation of the crowd, were several hundred Imperial cuirassiers under their colonel, Gilbert Sainte-Hilaire. The regiment was named after their first proprietary colonel: Count Heinrich Duval de Dampierre.

Count Heinrich Duval de Dampierre

Sainte-Hilaire had been sent to the Archduke’s aid by the only member of Ferdinand’s family not to have deserted him: his younger brother, Leopold, from Tyrol. The cuirassiers had ridden hard from the western Alps and reached Vienna via Krems. Their timing was impeccable. Ferdinand straightened himself up and noticed that the confidence of even the most brutal of his opponents had evaporated. Thurn was too much of a realist to try to settle accounts with Ferdinand surrounded by loyal cavalry. As Sainte-Hilaire’s men dismounted and with swords drawn raced up the stairs to the Habsburg, the rebels adopted almost instantly a very different mien. No more blood, they insisted, should be spilt. Thurn and his men bowed and withdrew.

Whatever the precise sequence of the encounter – and modern Jesuit historians challenge some of the details – there can be little doubt that had Ferdinand yielded that June day of 1619, the Counter-Reformation in his lands would have stalled and the Habsburgs would have ceased to play any further meaningful part in the history of Central Europe. With Bohemia and Lower Austria lost, the keys to Central Europe would have been surrendered. It is even likely that Catholicism would have become a minority cult practised north of the Alps only by a few scattered and demoralised communities.

For the army and the dynasty, the events of 5 June 1619 were no less critical. They had forged the umbilical cord which would bind them until 1918. Henceforth dynasty and army would mutually support each other. From this day there would be, for three hundred years, a compact between Habsburg and soldier, indivisible and unbreakable through all the great storms of European history. The army first and foremost would exist to serve and defend the dynasty.

For the next three centuries the generals of the Habsburg army would have the events of 5 June 1619 burnt into their subconscious and no commander would risk the destruction of his army, because without an army the dynasty would be put at risk. It was always better to fight and preserve something for another day than to risk all to destroy the enemy. This unspoken compact would snap only in November 1918 on the refusal of the last Habsburg monarch to use the army in a way that would risk their being deployed against his peoples.

The army benefited in many ways from these arrangements. As a symbol of this bond, Ferdinand II granted the Dampierre cuirassiers (and their successor regiments) the right to ride through the Hofburg with trumpets sounding and standards flying. Nearly two hundred years later, in 1810, the Emperor Francis I confirmed the privilege. The regiment could ride through Vienna and set up a recruitment office on the Hofburg square for three days. In addition the colonel of the regiment was to enjoy accommodation in the Hofburg palace whenever he wished and had the unique right of an unannounced audience with the Emperor at any time in ‘full armour’ (‘unangemeldet in voller Ruestung vor Sr. Majestät dem Kaiser zu erscheinen’).

These privileges were a modest recompense. The arrival of the Dampierre cavalry not only saved Ferdinand, it marked the turning of a tide. Five days later, on 10 June 1619 in Sablat near Budweis (Budějovice) in southern Bohemia, the Imperial forces under Buquoy defeated Mansfeld, the most able of the Protestant commanders, in the first Catholic victory of the conflict. This victory resonated throughout Europe and Ferdinand, having been written off barely a month earlier, now found himself receiving pledges of support not only from Louis XIII of France but from the many German princes who had earlier misinterpreted the winds of change blowing against the Habsburgs and had dismissed Ferdinand’s claims to the title of Holy Roman Emperor.

This title to which the Habsburgs had been elected since the fifteenth century carried mostly prestige. The Empire itself was, for all its insistence on its links with Charlemagne and before him the old western Roman Empire, an incoherent tapestry of different entities. In a world where influence was as important as power, the presence of a Habsburg as Holy Roman Emperor gave that family a dominating say in the affairs of the Germans. If Ferdinand could secure the Imperial title, which became vacant on the death in 1619 of his more tolerant cousin Mathias, it would cut the ground from beneath those rebels who had opposed his receiving the crown of Bohemia in 1617 and the crown of Hungary in 1618, men who with reason feared the Catholic orthodoxy which was Ferdinand’s touchstone.

Already, the Kurfürst (Elector) of Trier supported Ferdinand’s claim to the leadership of the Holy Roman Empire. The Catholic League led by Maximilian of Bavaria also declared itself for Ferdinand. At the last moment, the news in the autumn of 1619 came from Prague that the rebels in a desperate step had elected as their king the Protestant Elector Palatine, Frederick, a 25-year-old Calvinist and mystic who believed in a Protestant Union of Europe. But it was too late: Ferdinand had been elected two days earlier unanimously (even with the votes of the Palatinate) as Holy Roman Emperor or Kaiser. The new Kaiser set about impressing his authority on his domains immediately.