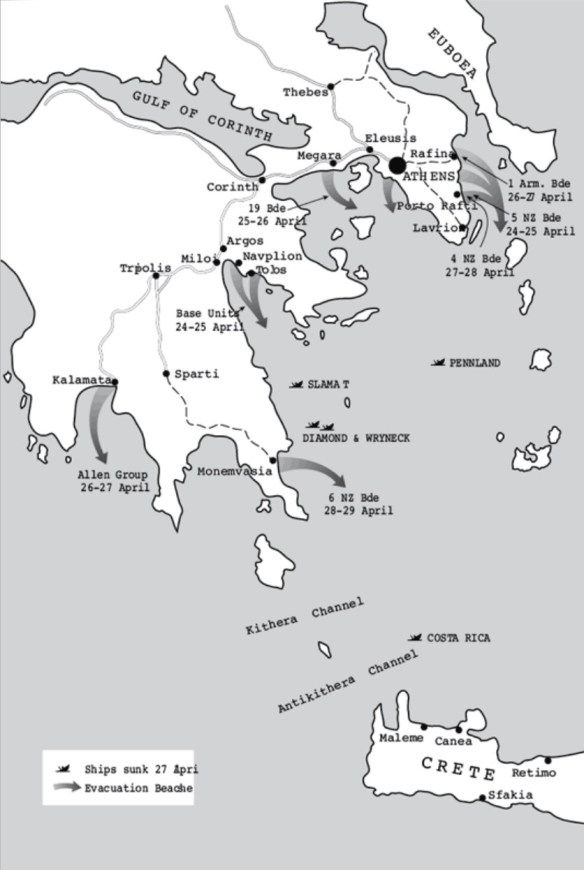

An Anzac Dunkirk: the evacuation beaches, and major force movements, April 1941

In different circumstances, Bob Slocombe, one of the survivors from 2/8th Battalion’s engagement with the SS at Vevi, managed to keep his tin hat, although the reasons for wanting to would later escape him. Slocombe was one of the Australians who ended up in the sea when Costa Rica finally foundered. He’d had the good sense to take off his boots in preparation for the swim but, inexplicably, he left his helmet on. A passing carley float (life raft) provided temporary respite, before he was picked up by another destroyer; still crowned with his helmet, Slocombe dried out on the engine-room gratings on the passage to Crete. Jim Mooney, one of Slocombe’s comrades in the 2/8th Battalion, recalled the miscalculations of other men, such as those who took off their boots and patiently tied a knot in the laces so they could hang them around their necks. Inevitably, when the boots filled with water and weighed them down, these men found their fastidious preparations no aid to their breast-stroke.

The sinking of the Costa Rica inflicted an unwanted diversion on the survivors. Instead of going back to Egypt, the survivors who had crammed aboard the three destroyers were offloaded at Suda Bay, Crete. In this chance way, these men were set on another path of tragedy and suffering.

While the Costa Rica drama played out, the Greeks awaited their fate on the mainland. Early on 27 April, the Germans finally entered Athens. On a ‘mellow spring morning, with an early nightingale singing in the pines and the hills glowing with wild roses’, mechanised columns entered the ancient birthplace of democracy.49 To complete the Nazi triumph, two German officers immediately hoisted the swastika on the Acropolis and just as quickly sent a telegram to their Führer, laying claim to the feat. This act of self-congratulation set off yet another spat in the ranks of the Wehrmacht, this time over who was entitled to claim the title of conqueror of Athens — the flag bearers or their commander. One Greek soldier, lying wounded in hospital, marked the occasion with a very different act of symbolism: he asked his nurse ‘to help him tie something up in his handkerchief’, which proved to be a handful of earth, since ‘he wished to save a little of Greek soil while it was still free’.

Some Anzacs were there to greet the Germans. Left behind at their hospital at Kephissia was Major Brooke Moore, a 42-year-old general practitioner from Bathurst, New South Wales, now commanding the six other officers and 150 non-commissioned ranks of the 2/5th AGH. With 112 patients too ill to move, the medical staff remained behind to care for them. Vince Egan was one of the hospital orderlies who, having spent the night on duty, awoke to be informed that he was now a prisoner of war. The Germans arrived at Kephissia on the morning of 27 April and placed a guard on the hospital, but otherwise allowed the staff to continue their work.

While the citizens of Athens contemplated occupation, the last military evacuations were still underway. By 27 April, Freyberg described conditions at the remaining embarkation beaches as ‘chaotic’. His 4 Brigade spent the morning moving into a defensive position near the village of Markopoulon, in order to block the road from Athens to Porto Rafti. This movement was detected by the ever-present Luftwaffe, which mounted a sharp raid before noon by 23 aircraft. These managed to start a fire in an ammunition wagon of the 2/3rd Field Regiment, with disastrous results: ammunition set off by the fire set in train a series of explosions, and ‘soon shells were bursting everywhere, vehicles burning, and the ripe crops in the fields and the trees in the pine woods blazing fiercely’. When the Australian gunners and the nearby New Zealand infantry of the 20 Battalion emerged from the mayhem, they left behind six artillerymen who had been killed, and 30 more Kiwis who had been killed or wounded. The loss in equipment was also severe — nine guns from the 2/3rd Field and an attached anti-tank battery were smashed and burnt. Warrant Officer C. V. Shirley, a 24-year-old clerk from Invercargill, was among the New Zealanders:

I was only about one hundred yards down the road when a number of aeroplanes swooped very low over the ridge. The men were still in their trucks, awaiting dispersal orders but immediately the attack began they scattered and took what cover they could on both sides of the road. The attack continued for some considerable time, the planes swooping very low up and down the road and strafing the road itself, the trucks and men. All the vehicles except the OC’s 8-cwt truck were ‘brewed up’ by incendiary bullets, which also set fire to [the] crop in which some of the men were sheltering.

Observing this devastation were the villagers of Markopoulon. With the Germans on their doorstep, and the sky black with smoke as their crops burnt, the Greeks stood outside their houses to cheer on the Kiwi infantry, and give what support they could — ‘Women and girls ran forward with cups of water and old men gave the thumbs-up sign.’ For good reason, many of the Anzacs interviewed for this book still had tears in their eyes 60 years later when they were asked to comment on the support they got from the Greek people.

Despite the air attacks, the 4 NZ Brigade got into position, and they watched mid-afternoon as a German column moved into Markopoulon. The Anzacs declined to fire into the village, and instead opened a barrage from field guns and mortars only when the German vehicles appeared from it. A determined attack did not eventuate, and this allowed Puttick to get his brigade and its attached artillery back that evening to Porto Rafti, where the cruiser Ajax, and the destroyers Kingston and Kimberley, carried away 3840 troops. At Rafina, the destroyer Havock took on another 800 men — the final elements of the 1st Armoured Brigade, with Charrington still in command.

One of the New Zealand infantrymen who embarked that night at Porto Rafti was Eric Davies with the 19 Battalion. He got out to the Kingston, and climbed the netting strung down the side to bring the troops aboard, initially in fine military order. Davies had both a rifle and a tommy gun, with ample ammunition for both, but made no allowances for the man above him, who panicked as they went up the side. When his comrade lashed out in fright, Davies was kicked off the netting. Weighed down by the hardware, Davies recalled, ‘I reckon I went down 25 feet, but by the grace of God, the net went that far, and I grabbed onto it. I got back up, ammunition and all.’

At Kalamata on 27 April, the only organised force was the NZ Reinforcement Battalion and the elements of the 2/1st Field Regiment and transport personnel under Lieutenant Colonel Haylock, marooned after the big embarkation the night before. The rest of the men at Kalamata were disorganised base troops under Brigadier Parrington. They spent the day beneath the olive trees, under regular air attack — the worst of them at dusk, when 25 bombers crisscrossed the town at only 500 feet, unloading sticks of bombs as they went. There would be no respite that night for the men at Kalamata. No naval force was sent there on 27 April, and so they had to wait another day to see if rescue was still a prospect the following night.

One of those waiting under the trees at Kalamata was John Crooks. He had set off from Athens with seven or eight of his own signallers, and along the way inherited about 120 other men. He recalled: ‘As the gathering collection of miscellaneous soldiers appeared to have no leader and I was the only officer in sight, I felt that I would have to show some sort of leadership and take the whole party with men.’

On 28 April, all was set for one final effort to shift the men from Kalamata. The only organised fighting force still ashore — Barrowclough’s 6 NZ Brigade — had reached Monemvasia after its rearguard work, and was also standing by to embark. Doug Morrison, at the head of his company in the 24 Battalion, spent his last days in Greece at Tripolis in the central Peloponnese, holding the road junction there which led to Monemvasia. Moving back to the port itself, Morrison’s men occupied a hill overlooking the bay, holding the very last perimeter of the campaign. By then his men were exhausted, and he recalled that ‘chaps were sleeping on their feet’.

For some, the Greek campaign ended on 28 April, and with it, their fighting careers. The Australian Reinforcement Battalion managed to move down the coast to Tolos from Navplion after it was left behind on the 26 April, but even this exertion proved to be in vain. While waiting at Tolos for embarkation, this isolated group was overrun by the Germans, and the greater part of it was forced to surrender. Some scattered parties took to the hills, and some others took their chances in small boats; but, for most, long years of captivity began that day.

Better luck attended Barrowclough and his men. On the evening of 28 April, with its discipline intact, the 4 NZ Brigade formed up on the causeway between Monemvasia and the mainland. Heading their way was first the destroyer Isis, followed shortly thereafter by the hardworking cruiser Ajax and the destroyers Hotspur and Havock. On the voyage north, Havock swooped in the darkness on what she thought was a submarine — but the small object in the sea proved to be a rubber dinghy carrying the crew of a spotter plane that had been catapulted off Perth earlier in the day. This machine was a ‘Walrus’ biplane amphibian, a wonderful contraption of pusher engine, high-mounted wings, and bracing wires, which ironically emanated from the same stable as the sleek Spitfire of Battle of Britain fame. The Walrus, unfortunately, had come across a prowling Junkers 88, which had quickly dispatched the Australian spotter plane. Closing in to depth-charge what she thought to be a submarine, Havock recognised her error at the last minute, and the hapless aviators became the first rescued souls for the evening.

At Monemvasia, the New Zealand troops formed up in good order at five points along the causeway, and were carried to the warships on board landing craft left behind by Glenearn. Baillie-Groham, waiting for embarkation along with General Freyberg, thought their organisation and discipline ‘magnificent’. Peter Preston’s platoon of the 26 Battalion was even ordered to shave and clean up before embarkation, to ensure that the brigade went away with the correct bearing. Setting this standard was Freyberg himself. Preston remembers the general striding the quay, demanding in his ‘funny, high-pitched voice, “Who’s in charge of that boat?”’, when something went even slightly awry. Freyberg’s equanimity was largely a show for the troops, as the general was actually a bundle of nerves:

I feel sure those last hours of waiting on the beach were the most anxious that we had had. The ships did not arrive to time. At 11.30 there were no ships in sight and we were in a state of desperation for, given the most favourable circumstances, I considered that anything up to 1500 troops would be left behind. Another difficult situation faced us. Suppose they did not turn up at all? Spread out all over the area were over 100 vehicles, we had our stretcher cases out on the pier and there were also walking wounded … the anxiety of those last hours was indescribable.

‘When, lo, out of the darkness, there was light

There in the sea were England and her ships.’

Without major mishap, the troops were embarked; so, by 3.00 a.m., after a last sweep of the beach by Freyberg and Baillie-Groham to see that no stragglers had been left behind, the New Zealand general and the British admiral were at last aboard the Ajax.

Further south at Kithera, a smaller evacuation mounted by Auckland, Salvia, and Hyacinth was also a success that night. Unfortunately, the good luck ended at Kalamata. There, 7000 troops remained, together with 1500 Yugoslav refugees, whose likely fate in German hands was too hideous to contemplate. Coming to their aid was a powerful convoy of warships, led by Lieutenant Commander Bowyer-Smyth aboard Perth, together with another cruiser, Phoebe, and the destroyers Decoy and Hasty. Sailing north, these ships were joined by four more destroyers, Nubian, Hero, Hereward, and Defender, the whole group aiming to arrive at Kalamata at 10.00 p.m. To undertake a reconnaissance, Bowyer-Smyth sent ahead Hero, commanded by Captain Biggs, at 7.30 p.m. Good practice though this reconnaissance might have been, it unfortunately did more harm than good. Nearing the port at 8.45 p.m., Biggs saw evidence of fighting in the town as tracer fire lit the night, and someone on the breakwater then signalled the destroyer, ‘Bosch in town’.

Indeed they were. An assault party of two companies of the 5th Panzer Division, with two field guns, had attempted a daring coup by storming the town. One of the units awaiting embarkation was the New Zealand reinforcement camp: it held men from 31 different units of the 2nd NZEF, awaiting orders to go forward as replacements. With the help of a number of officers, Major MacDuff organised the men into a battalion headquarters and three rifle companies, and these preparations were warranted. At around 5.00 p.m., the German column suddenly entered the town and got as far as the quay, where they captured the naval sea-transport officer in charge of the embarkation, Captain Clark-Hall.

Small groups of New Zealand and Australian infantry quickly counterattacked, many not even needing orders before pitching in. Sergeant Jack Hinton of the 20 NZ Battalion was one of the men from the reinforcement camp who took matters into his own hands. Fighting his way through the town, Hinton was finally faced at a distance of 200 metres by a post of two machine-guns and a mortar, placed to cover one of the German field pieces. One of his 20 Battalion comrades, Private Jones, recalled:

Hinton started off again and in a very short time cleaned out the two LMGs and the mortar with grenades. Simultaneously a 3-tonner driven by an Aussie and carrying a load of Kiwis rushed the heavy gun from the south. I cannot say whether Hinton or the chaps on the truck cleaned up the big gun. A few minutes after this episode, which was really the turning point of the whole show, Jack was severely wounded in the stomach.

For his bravery in this action, Hinton was awarded the Victoria Cross. Pockets of Germans armed with machine pistols fought it out from the balconies of houses along the quayside, before being persuaded to surrender. The defenders had killed 41 Germans, wounded more than 60, and taken between 80 and 90 prisoner.

Still waiting in the olive groves, John Crooks was a witness to this battle. With his sergeant, he made to enter the town looking for instructions:

[W]e set off on our own to walk along the road in the direction of the town and the pier. I estimated it was about two kilometres ahead of us. At this time sounds of a fierce battle developing could be heard. Almost immediately a shell burst some 15 yards to our left and a little ahead of us. This shell killed one of two British soldiers who were also attempting to find out what they ought best be doing. I … judged it would not be prudent to proceed further. What with the gathering darkness and with no troop dispositions or password known, the possibilities were ripe for either side to have a shot at us, so we walked back to our olive grove hiding place.

While the battle raged along the harbour front, out at sea on board Hero, Captain Biggs acted to clarify the position ashore, landing his first lieutenant in search of Parrington. Biggs’ signal to Bowyer-Smyth to indicate the presence of the Germans reached Perth at 9.10 p.m. Without waiting for a further assessment, or even asking for one, Bowyer-Smyth turned the rest of his force around at 9.29 p.m., abandoning the Kalamata troops to their fate. Bowyer-Smyth subsequently justified his decision on the grounds that his warships were too valuable to risk, and that fire from fighting ashore would silhouette his force and leave it vulnerable to attack by enemy surface vessels. There were no signs of such enemy intervention and, in an any event, Pridham-Wippell had already accepted the risk of loss when Bowyer-Smyth’s force was sent north. By the time Biggs established that evacuation was still possible, Bowyer-Smyth was long gone. Joined by three other destroyers — Kandahar, Kingston, and Kimberley — Biggs took on board Hero as many troops as he could, but this amounted to only 332 men. One of the lucky few was Kevin Price of the 2/1st Anti-Tank Regiment, who had been in the first action of the campaign at Vevi and was now one of the last off. Carrying a heavy Boys rifle, Price walked out into neck-deep water to scramble aboard a boat taking troops out to the Kingston. Safely on the destroyer, Price took a mug of hot cocoa. He remembered thinking, ‘[This is] the best drink I’ve ever had.’ Then he lay down on the deck and did not move until the Kingston reached Crete the next day.

Admiral Cunningham wrote later that Bowyer-Smyth had come to an ‘unfortunate decision’, but his reaction at the time suggested an even stronger sense of disapproval. Under his direct orders, the destroyers Isis, Hero, and Kimberley were sent back to the Kalamata area the following night, 29 April, to see what could be done. By then, as predicted by Parrington, the Germans had arrived at Kalamata in force and had compelled most of the remaining troops to surrender. John Crooks was one of them. According to him, at about 8.00 a.m. on 29 April, ‘a solitary German soldier, not much more than five feet tall, nonchalantly walked along the road with rifle slung casually over his shoulder and shepherded [the remaining troops] in a slow march into and through the town of Kalamata’.

The following night, Isis did pick up a boatload of New Zealanders who had managed to get 16 kilometres out to sea; with them, a sweep of the shore netted a total of 202 troops When some of these claimed to be Australians, their identity in the darkness was established by the destroyer crews asking the question, ‘What was Matilda doing?’ Cunningham sent ships north for the last time on 30 April. With another handful of stragglers rescued that night, the naval effort had managed to get away from Greece the grand total of 50,662 men, not counting the various parties making their way through the Aegean islands.

In this way, the Anzac campaign on mainland Greece ended. Whatever its motives, whether it was the mirage of a Balkan Front, a desire to impress American public opinion, the need to uphold British honour by helping the valiant Greeks, or some combination of all these, the cost of the campaign was high. Of the Australian contingent, 320 lay dead in Greek graves, another 494 were wounded, and 2030 began four long years as prisoners of the Germans. The Kiwis fared little better: 291 New Zealanders were dead, 599 wounded, and 1614 made prisoner. Militarily, the cost would be measured not only in casualty lists, but in foregone strategic opportunities, and the fragmentation and dispersal of first-class units like the 6th Division AIF and the New Zealand Division.

The Greek campaign was not just a failure in its own right, but it meant that the chance to finish the war in North Africa in 1941 was lost, forcing Britain and her empire to spend time, money, and lives that might have been better expended securing Malaya, Singapore, and Australia against the Japanese threat. Churchill, however, was well pleased, telling Wavell on 28 April that the whole campaign was a ‘glorious episode in the history of Britain’ which had greatly impressed the Americans.