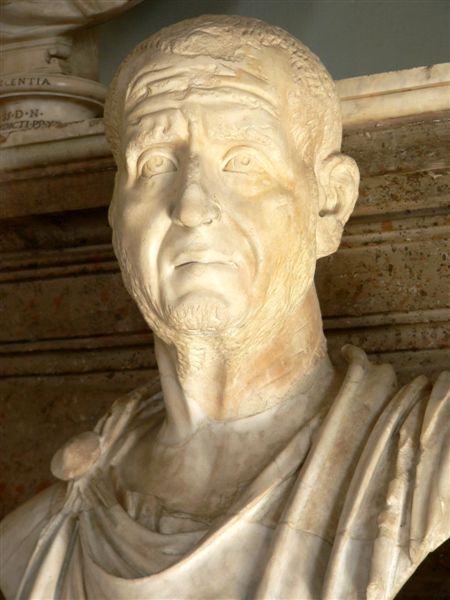

Bust of Trajan Decius

In the end, Decius did not reign long. Yet he is one of the most famous emperors of the third century, not on account of his extraordinary coinage but for another measure altogether: an order for universal sacrifice to the gods, for the good of the Roman state. Like the new coin types, it was meant to signal a new beginning, the return of prosperity to the empire, but for it to work, everyone would need to sacrifice. The plan for carrying out the new emperor’s order was modelled on the collection of taxes and registration for the census, and the evidence for it survives to a remarkable degree in the papyri of Egypt. These papyri are libelli that record a citizen’s act of sacrifice to the ‘ancestral gods’ before public officials, who are named in the documents as having presided over the act of sacrifice and the consumption of sacrificial food. As with census registration for tax purposes, the inhabitants of each province were assigned a day on which they were required to appear before their municipal magistrates to perform sacrifice by burning incense to the gods, and were then issued with a chit proving that they had done so – with failure to comply carrying serious consequences. This devolution of imperial directives on to local authorities is entirely characteristic of the way regional administration worked in the early empire, but we know much more about Decius’s edict than most others, for two reasons: one being the survival of the Egyptian libelli; the other being the impact it had on Christians.

Although the edict’s wording was vague, and did not specify which or whose ancestral gods were being referred to, Christians seem to have interpreted the order as requiring them to sacrifice to the gods of the Roman state. Christian monotheism rejected any distinction between belief and cultic acts. Christians were prohibited from worshipping any gods but their own one god, and they regarded the many other gods they saw all around them as demons. Most Christians, that is to say, believed full well in the gods of the Roman state, knew them to be quite real, but regarded their reality as demonic rather than divine. An order to sacrifice along the lines of the Decian edict could not help but challenge them. Choosing to comply meant not just sinning, but exposing their souls to eternal damnation. Failure to comply, by contrast, meant exposing each one individually to the more immediate bodily vengeance of the Roman state. Thus, whether or not Decius had intended it as such, it was impossible for Christians to interpret his edict as anything other than a deliberate attack on them and their beliefs. Decius is duly remembered by Christians as the second of the great Roman persecutors after Nero, the scale of whose persecution is much exaggerated.

Decius’s intentions have long provoked debate. Some elements of his plan are uncontroversial. He clearly believed that a single, unifying ritual act was necessary to please the gods and ensure the state’s safety. Perhaps he was mainly concerned with shoring up his own rather weak claims to the purple. Perhaps he was responding to millenarianism provoked by Philip’s celebration of Rome’s thousandth anniversary. He may also have been influenced by the outbreak of a new and frightening disease that was taking hold in the eastern parts of the empire: beginning in 249 in Alexandria, a severely contagious illness that caused high fever and conjunctival bleeding had begun to spread across the empire. Fading away in high summer, it returned in autumn, reaching Rome and Carthage by 251 at the latest and recurring periodically for at least a decade thereafter. The precise virus responsible cannot be determined, but scholars have recently begun to recognise just how serious it was, affecting town and country, rich and poor, and killing off as much as two-thirds of the population in some cities, if our better sources are to be believed. Haemorrhagic fever similar to the Ebola virus has been hypothesised: the combination of seasonality with high morbidity and mortality makes a filovirus of that sort a likely candidate. As the recent Ebola outbreak shows, the sudden impact of a new epidemic can prompt hysteria and the demand that our leaders take drastic measures to save us. We should not be surprised if ancient people, lacking modern epidemiological knowledge, thought it necessary to propitiate angered divinities, and worried that those who habitually refused to honour the gods were responsible for their anger.

Whatever the admixture of foresight and reaction, or of reason and hysteria, that lay behind the Decian measure, we also need to understand it as an early fruit of the equestrianisation of the empire – the increasing dominance of men of equestrian rank with bureaucratic careers, and the type of ‘governmentality’ that went with that. Decius undoubtedly remembered Caracalla’s citizenship edict, with its universalising rhetoric and still-more universalising impact in extending Roman law to the whole imperial population. Almost forty years after the Antonine constitution, a whole generation whose parents had been born as non-citizen peregrini was having to negotiate an adherence to Roman laws that were entirely outside the customary behaviours of their locales. Experienced administrators like Decius were aware of this before and after, and will have seen an ideological value in this universal conformity. We should thus think in terms of two governmental impulses, each functioning in parallel to the other: Caracalla’s grandiose edict had made it possible to imagine the whole of the empire as a single world in which all could and should do things the same way; at the same time, equestrianisation and the relentless expansion of governmental routine made the aspiration to enforcing such uniformity seem both possible and achievable.

The ad hoc nature of early Roman government had stemmed from a recognition that ruling the empire could be done most cheaply, peacefully and efficiently if local customs and local ways of keeping the peace and extracting tribute were maintained – and also from the incapacity of a polity that had developed out of the familia and clientela of Augustus to administer an empire of such scale according to uniform rules. Two centuries of expanding government and structural stability had altered that picture, so that what was once both inconceivable and unnecessary could now seem both possible and worth having. Whatever else we see in Decius’s edict to sacrifice – and it is clear that later emperors who ordered the deliberate persecution of Christians did see his edict as a model – we should also see it as an important stage in the development of a specifically late imperial approach to government, one that reached its fullest expression in the fourth century, and was thereafter sustained for a century or more in the west, and for a full three centuries in the east.

Decius’s assertiveness extended to more than matters of religious practice or the power of the state. He seems also to have been intent upon asserting himself as a more effective military leader than Philip had been. We have already seen how changes north of the Black Sea and east of the Carpathians had seriously altered the balance of power there, with the imposition on a settled agricultural society of a new military elite whose culture combined elements of central European dress and language with fighting styles and decorative schemata from the steppe. By 249, Roman military planners were conscious enough of these changes that Decius sent soldiers to the Bosporus to report on developments, the rump of the Hellenistic Bosporan kingdom still hanging on as the world changed around it. Along the lower Danube, meanwhile, Philip had exacerbated an already bad situation by stopping traditional subsidies to the Carpi and campaigning against them, alleging that they had broken the peace with Rome. But the withdrawal of imperial subsidy was rarely a successful technique of frontier management: Decius had personally to lead an army to Moesia Inferior against barbarians who are variously called Carpi, Borani, Ourogundoi and Goths by sources with some limited claims to authenticity, and are generically known as Scythians by the contemporary classicising authors. The confusion of names attested in the sources is a fact of prime historical importance: contemporaries on both sides of the frontier had little real idea of what was going on. Only with hindsight can we understand these events as the by-product of a developing Gothic hegemony in the whole region, in consequence of which the barbarian polities along the fourth-century Danube bore little traceable relationship to those of the third.

We need to resist the temptation to paste our disconnected pieces of evidence into a single, neat narrative, but the one thing we can say with certainty is that Decius faced a truly disastrous situation when he led his army into Moesia Inferior, where an invading army of Scythians had placed Marcianopolis under siege. Newly discovered fragments of the Athenian historian Dexippus have confirmed details known from much later sources whose authenticity has been doubted, and it is now clear that several groups of Scythians were led by commanders named Ostrogotha and Cniva, and that they inflicted heavy losses on the emperor himself at Beroea. News of this debacle probably triggered a short-lived coup in Rome by the senator Iulius Valens Licinianus, but that appears to have been suppressed almost instantly, perhaps by the praetorians, for no coins were struck in Valens’s name. Then, back in the Balkans at either the end of 250 or early in 251, Philippopolis did fall to Cniva’s invaders, after a short-lived usurpation by the governor of Thrace, T. Julius Priscus, had taken place there. Finally, in the first half of June, Decius confronted the invaders at Abrittus, north-west of Marcianopolis, in a pitched battle that went disastrously wrong. His opponents had dug themselves in across treacherous, marshy terrain ill suited to the mass infantry engagements at which Roman armies generally excelled. In a monumentally foolish move, Decius personally led his forces into battle across the marsh, where they became entangled and were massacred. The emperor himself died, as did his son Herennius Etruscus, and his body was never recovered. Later Christian authors could gleefully imagine this as the condign fate that awaited persecutors: ‘as an enemy of God deserved, he lay stripped and naked, food for the beasts and the carrion birds’.

News of the disaster reached Rome in mid June, as did word that the troops had raised C. Vibius Trebonianus Gallus, governor of Moesia Inferior, to the purple. He negotiated the withdrawal of the Scythians back across the Danube, though it appears that they took a large part of Decius’ imperial treasury with them: what had been a silver-based economy north of the imperial frontiers was rapidly transformed into one based on gold, with aurei of Decius seized at Abrittus its primary model. As soon as the Scythians departed, Gallus returned to Rome with great haste, arriving there in late summer. Gallus was an Italian of high rank – that we even know the name of his father, whose career was underway during the reign of Septimius Severus, is rare enough in this period to mark the family’s distinction. Despite ongoing trouble on the eastern front, Gallus’s hasty journey to Rome was a wise idea: the symbolic conciliation of senate and plebs remained a necessary duty if an imperial acclamation was to win any long-lasting acceptance, and Gallus issued adventus coins to commemorate his arrival. The senate swiftly consecrated the dead emperor as divus Decius, and Gallus at first accepted the latter’s younger son Hostilianus as a caesar alongside his own son Volusianus. It is unclear whether or for how long this situation lasted: there is some evidence that Decius suffered damnatio memoriae along with his sons, but it is not widespread enough for us to be sure and may instead reflect later Christian defacement of the hated persecutor’s name. Certainly, the surviving son Hostilianus was either put to death or died of natural causes before the year was out. At any rate, before the middle of 251, only two emperors were recognised by the senate, C. Vibius Trebonianus Gallus and his son, C. Vibius Volusianus, the caesar and princeps iuventutis. Senatorial approval or acquiescence having been vouchsafed, however, more pressing matters needed attention.

The revolt of Iotapianus had been suppressed either at the end of Philip’s reign or at the beginning of Decius’s, in circumstances that remain unknown to us, but a new revolt had broken out led by an Antiochene notable with the Syrian name of Mariades. By the time imperial troops loyal to the Italian regime got properly involved, Mariades determined to flee to Persia and seek refuge with Shapur. Shapur, in his victory inscription, claims that Rome had violated the peace that Philip made in 244 by sheltering the Arsacid heir Tiridates of Armenia, who had sought refuge with the Romans after his father Khusrau II had been assassinated, probably at Shapur’s instigation. In response, Shapur annexed Armenia, eliminating its Arsacid rulers and placing it under the rule of his son Ohrmazd.

Much more elaborate versions of these events survive in the Armenian tradition, with added folkloric elements of subversion, betrayal and massacre. One detail they preserve that may have some value is the extent to which the elder Tiridates and Khusrau had been irritants to Ardashir and then Shapur, promoting rebellions as far away as the Kushanshahr – which would help to explain the amount of time Shapur had to spend fighting in the east. Now, with the strategic mountain kingdom of Armenia in his possession and his eastern frontiers secure, Shapur again turned against the Romans, assisted by the rebel Mariades. In 252 or 253, the shahanshah attacked the Syrian provinces, not by the usual approach via Singara, Resaina and Carrhae, but by an unexpected route that caught by surprise the whole Roman garrison of Syria, which was being brought together in anticipation of a Persian campaign.

Shapur claimed that in this victory, at Barbalissos on the Euphrates, he defeated a full 60,000 Romans – a number that, even if wildly exaggerated, speaks to a major Persian victory. Antioch itself, along with other important Syrian cities like Hierapolis, were taken in this campaign or campaigns, Persian armies advanced as far as Cappadocia, and the Italian government of Trebonianus Gallus was powerless to do anything about it. Shapur deported a great many captives to Khuzistan, where he founded a new city that he called Veh Antiok Shapur (‘Better than Antioch Has Shapur Founded This’), a name that was later corrupted into Gundeshapur, an important town in the zone between the Zagros and the Tigris. Shapur’s motives went beyond military glory: Khuzistan was to become the economic engine of the Sasanian state, peppered with industrial centres, many populated by deported captives, specialising in production that enhanced the royal revenue and paid for further conquest. By suppressing older towns – perhaps most importantly Susa – with traditions of independent government and favouring instead royal centres governed directly by the imperial administration, Shapur inaugurated a long-standing policy that made the Sasanian dynasty the richest and most powerful of the ancient Near Eastern empires

In the third-century moment, however, the failure of the Roman emperors to act meant local easterners were compelled to take matters into their own hands. It may be at this time that Odaenathus, a nobleman from the flourishing caravan city of Palmyra, and an intermittently important figure in eastern affairs until his assassination in 267, came on the scene, but the chronology of events in this period is almost hopelessly tangled: some would attribute to this Odaenathus the defeat of a part of the Persian army that others attribute to one Uranius Antoninus of Emesa. That obscure figure’s full titulature – Iulius Aurelius Sulpicius Severus Uranius Antoninus – clearly proclaimed his kinship with the Severan house. He may have been a devotee and priest of Elagabal, the god of Emesa, and if so he was perhaps a relative of the family of Julia Domna. Given that he minted coins, which are the best evidence we have for his existence and his sphere of activity, it seems clear that Uranius was actively challenging Gallus’s claim to the imperial throne. In the later romanticised version of John Malalas, a sixth-century author who related a great deal of local Antiochene lore of varying reliability, Shapur himself is said to have been killed in this Emesene encounter, although the usurper Uranius has been blotted out and replaced by a noble priest named Sampsigeramus. While the story is clearly fiction, Emesa is conspicuously missing from the list of cities Shapur claims to have conquered in his inscription at Naqsh-e Rustam, and it seems very likely that he suffered a substantial defeat there. The fact that it took place at the hands of a local ruler, rather than an army even putatively loyal to the legitimate emperor, reminds us of the ongoing difficulty western emperors faced in retaining control of the east, in part because of their inability to protect the eastern provinces from Persian threats: it was not that they did not want to act, but that other threats constrained them. Thus Trebonianus Gallus could not, in 253, have acted upon the devastating news from the east even if he had wanted to, because he was facing the threat of another rebellion, closer to home and thus more immediately dangerous.

This new challenge was triggered by events that should now be numbingly familiar to the reader: a general on the frontier wins a battle against some barbarians, takes the purple, marches against the reigning emperor, and both would rather allow the provincials to suffer than let their rival gather momentum. As so often, the state of the sources leaves us guessing about details, but it is pretty clear that although Gallus had neutralised the group of Scythians that had taken Philippopolis and killed Decius, these were just one small part of a larger problem: because there were as yet no organised polities beyond the Danube with whom to treat, no single ethnic or tribal group responsible for the problems the empire was facing, the suppression of one challenge meant nothing for the status of many others. Thus the Scythians with whom Gallus had dealt might very well have respected their treaty with him, but that left dozens of opportunistic raiders happy to take advantage of imperial distraction and weakness. So it was that in 252 there were major seaborne raids into the Aegean from the Black Sea, presumably by barbarians who had joined with, or conquered and seized the resources of, the remaining Bosporan Greeks. The raiders were successful and elusive and, although it is hard to gauge the actual level of damage, some of what they did was quite shocking to contemporary sensibilities, for instance, the burning of the temple of Artemis at Ephesus in Asia Minor, one of the most famous shrines of antiquity.

Then, in 253, Moesia Inferior was invaded by a different group of Scythians, who this time met with effective resistance from a general named Aemilius Aemilianus, about whom precious little is known. He was probably born in the first decade of the century, starting a career under Severus Alexander and rising through the ranks, but that is about all we can say. Now he demonstrated a fact that was becoming obvious to everyone – the loyalty of provincial armies to a distant emperor was impossible to guarantee. Aemilian’s victorious troops declared him emperor and, though there was no way the Balkan frontier could yet be considered secure, he turned immediately to the march on Italy, necessary if he was to secure his hold on the purple. Crossing into Italy, he met and defeated Gallus at Interamna in Umbria. Gallus and the caesar Volusian were killed by their own troops and Aemilian won the recognition of the senate, who also acclaimed his wife Cornelia Supera the augusta. But Aemilian’s reign was to prove a short one. As soon as Gallus received news of the uprising, he sent word to Gaul to summon support from Publius Licinius Valerianus, more generally known as Valerian. The latter heard of Gallus’s death while still en route to Italy, and in Raetia he was proclaimed emperor in turn. In September 253, during the same campaigning season in which he had first been proclaimed, Aemilian was killed in battle with Valerian’s army at Spoletium in central Italy. The rapid turnover of emperors had become bewildering. The reign of Valerian would last somewhat longer, but would be no less traumatic for the high politics of empire.