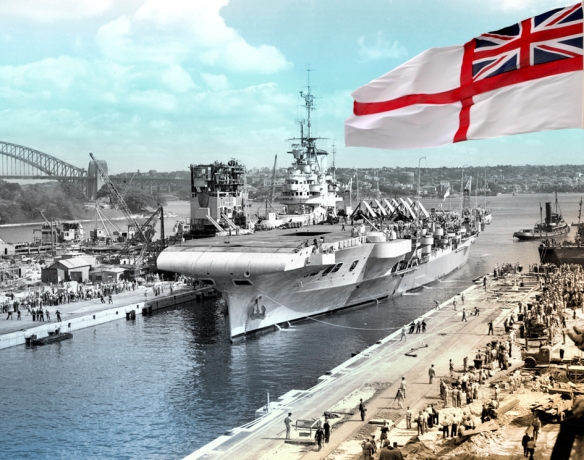

HMS Illustrious entering the Captain Cook Graving Dock, Sydney 11 February 1945.

The replenishment carrier HMS Fencer.

With Japanese air power in the Philippines finally defeated, Halsey took the Third Fleet into the South China Sea, attacking harbours and shipping over an area of sea stretching from Saigon in French Indo-China, now Vietnam, and Formosa over the period 10–21 January 1945. The carriers’ aircraft met little resistance and 200,000 tons of enemy shipping was sunk. The Kamikaze re-emerged, however, and both Ticonderoga and Langley were hit. Nevertheless, by the spring most of the southern Philippines were controlled by American forces.

The Japanese were left in no doubt now that the net was tightening around them. On 16 and 17 February, with the fleet redesignated the Fifth Fleet once more and under the command of Admiral Raymond Spruance, Mitscher took the sixteen carriers of what was now Task Force 58 with nine battleships, fourteen cruisers and seventy-seven destroyers, to launch the first large-scale attack by the United States Navy on the Japanese home islands. The primary targets were Japanese airfields, against which the Navy’s fighters and fighter-bombers could be more effective than the USAAF’s heavy bombers which were concentrating on the cities. In the operation more than 500 Japanese aircraft were destroyed against eighty-eight of the strike force and its fighter cover. The cruel reality of Japan’s predicament was by this time clear for all of the population to see, as there could be no disguising the impact of the bomber campaign, which used incendiary bombs that proved highly effective against the largely wood and paper construction of Japanese homes.

The attacks by the long-range bombers on Japan from their bases in the Marianas were thought to be vulnerable to Japanese fighters, although this problem was to ease considerably with the introduction of the high-flying Boeing B-29 Superfortress. Meanwhile, to provide fighter cover for the bombing raids, bases were needed for the fighters much closer to Japan itself, and the island of Iwo Jima was seen as ideal. On 19 February the first American forces landed on Iwo Jima, covered by the Fifth Fleet with TF58’s carriers. The actual landing saw Vice-Admiral Turner’s TF51 with 500 ships put Lieutenant General Smith’s V Amphibious Corps ashore, with direct support provided by seven battleships, eleven escort carriers and five cruisers. Ashore, there were 20,000 Japanese troops in well-defended positions. The Kamikaze attacks on 21 February against the Bismarck Sea and Saratoga. It took a month and 23,000 American dead and wounded for Japanese resistance to be broken.

Having established a strategy of attacking Japanese airfields within reach of the next landing objective, it was necessary for TF58 to attack Japan once again before the landings on Okinawa, a measure of the island’s proximity to the home islands and the air bases which could have sent aircraft to attack the invasion fleet. On 18 and 19 March carrier aircraft once again struck at airfields and naval bases in Japan itself, using 1,200 aircraft from the carriers Hornet, Bennington, Enterprise, Franklin, Essex, Bunker Hill, Hancock, Yorktown, Intrepid and Wasp, as well as the light carriers Belleau Wood, Bataan, San Jacinto, Langley, Independence and Cabot. The carriers were supported by the battleships Massachusetts, Indiana, North Carolina, Washington, South Dakota, Wisconsin, New Jersey and Missouri, as well as the battlecruisers Alaska and Guam, plus sixteen cruisers and sixty-four destroyers.

Ashore in Japan, Vice-Admiral Ugaki organised a counter-attack, including his own Kamikaze force, with hits on the aircraft carriers Franklin, Enterprise, Intrepid, Yorktown and Wasp. Of these, Franklin suffered most, with 1,000 casualties among her ship’s company after just two 550lb bombs had penetrated her flight deck, smashing their way into the hangar and exploding among armed and fully-fuelled Avengers, Helldivers, Hellcats and Corsairs waiting to be taken up to the flight deck for a further strike. The carrier was put completely out of action by the chain of explosions and the holocaust that followed, and was the only Essex-class carrier to come near to being lost. Nevertheless, in an outstanding feat of damage control, the ship was saved and was taken to Pearl Harbor for major repairs. The fact that she never returned to service after rebuilding and recommissioning but was eventually scrapped was largely due to the normal peacetime reduction in naval strength post-war.

THE BATTLE FOR OKINAWA

At the end of March 1945 the US 77th Infantry Division was landed on the Kerama Islands, finding them lightly defended, and a forward naval base was quickly built ready to support the forces that would be tackling the toughest objective encountered so far, Okinawa. Battling through heavy seas and high winds on their way to the beachheads, US forces landed on Okinawa on 1 April 1945 to find Lieutenent General Ushijima and almost 80,000 troops, as well as a further 10,000 naval personnel based on the island who were also pressed into service. The defenders had well-prepared positions, especially on the south of the island. The landings were once again covered by the US Fifth Fleet under Admiral Spruance, and within this force was both Mitscher’s TF58 with its ten large and six light carriers, and TF57, the British Pacific Fleet under Vice-Admiral Sir Bernard Rawlings with its force of 220 aircraft aboard four carriers under Rear-Admiral Sir Philip Vian. The British also had the battleships King George V and Howe, five cruisers and escorting destroyers. While TF58 was to suppress Japanese air power on Okinawa, TF57, as already mentioned, was to protect the left flank of the US Fifth Fleet and stop the Japanese moving aircraft across the islands of the Sakishima Gunto. There was also TF51 under Vice-Admiral Turner with 430 transports and large landing ships, with close cover provided by the battleships New Mexico, Maryland, New York, Arkansas, Colorado, Tennessee, Nevada, Idaho, West Virginia and Texas, eighteen escort carriers with 540 aircraft, and thirteen cruisers. These ships were only the spearhead of the assault, as the Fifth Fleet also included tankers, aircraft transports (escort carriers with replacement aircraft), vessels that were floating workshops and ocean-going tugs.

The initial landings were by the US Tenth Army, under Lieutenant General Buckner, on the west coast of the island and at first resistance was very light. In fact, once again the Japanese response initially seems to have been slow in coming, and it was not until 6 April that a battle group consisting of the giant battleship Yamato, sister of the ill-fated Musashi, put to sea heading for Okinawa escorted by a cruiser and eight destroyers, while at the same time, a fresh Kamikaze offensive began. The following day, Mitscher sent 280 USN aircraft to find and attack Yamato, sinking the battleship and the cruiser as well as four of the destroyers, leaving just four to escape. Nevertheless, the Kamikaze attacks proved to be the most concentrated of the war with 2,000 pilots sacrificed by the Japanese, with the campaign lasting for six weeks, and no less than twenty-six Allied ships were sunk although none of them larger than a destroyer, while another 164 ships were damaged. Those ships damaged included the aircraft carriers Intrepid, Enterprise, Franklin and Bunker Hill as well as the British Formidable, Indefatigable and Victorious and the battleships Maryland, Tennessee and New Mexico.

Enterprise was hit by a suicide aircraft on 11 April, and was forced to suspend flying operations for forty-eight hours:

‘When a Kamikaze hits a US carrier, it’s six months repair at Pearl,’ commented an American liaison officer surveying the after-effects of a Kamikaze attack aboard a British carrier. ‘In a Limey carrier, it’s a case of ‘‘Sweepers, man your brooms!’’’

This might have been an over-generous appraisal of the situation, but it was certainly true that the Royal Navy’s six fast armoured carriers proved the value of their armoured flight decks and hangar sides and decks during the Kamikaze campaign.

Command of the Japanese air counter-attack was in the hands of Admiral Soemi Toyoda, and his air offensive was timed to coincide with the start of the sustained Kamikaze attacks on 6 April. Out of the 900 aircraft that attacked the US Fifth Fleet on that day, 355 were Kamikaze. TF58 claimed to have shot down 249 aircraft and of the 182 estimated to have struggled through the fighter cordon, 108 were shot down. The terms ‘claimed’ and ‘estimated’ have to be used, since sometimes more than one fighter pilot or AA gunner would claim to have shot down an aircraft, and despite rigorous checking by intelligence officers afterwards, completely accurate figures can be difficult to find. It is conceivable, for example, that a fighter pilot having seen an aircraft heading downwards in flames would claim it as one of his score, while if the aircraft continued towards a ship and was then caught in its AA fire, that would also claim it as part of its score.

This was by now a war of attrition. Between 6 April and 29 May, 1,465 aircraft from one of the Japanese home islands, Kyushu, were used in ten massed Kamikaze attacks. Of these aircraft, 860 came from the Japanese Navy Air Force’s Fifth Air Fleet and the remainder were from the Japanese Army Air Force’s Sixth Air Army. Another 250 aircraft appeared from Formosa, now Taiwan, with around 80 per cent of these being from the JNAF. In addition, the JNAF mounted a further 3,700 conventional sorties and the JAAF a further 1,100.

The operations of the Fifth Fleet demonstrated considerable flexibility. On 9 April, with the need for additional sorties over Okinawa, TF57 was called upon to attack airfields in the north of the island, while its role of keeping the airfields on the Sakishima Gunto under constant attack was taken over by the escort carriers of TF51. The Admiralty Naval Staff History of the campaign referred to TF51 as having to do all of the odd jobs, describing this as:

… the backbone of the attacks against the defence installations, and provided the close support for the assault of the western islands … It was apparent that this force realised what was required of it far better than did the fast carrier force, and its pilots were far more assiduous in engaging concealed defences.

After Okinawa fell, the Allies were able to examine the Okha flying bombs for the first time, including the later version, the Okha III, powered by three rockets and with a 4,500lb explosive charge which had it hit a carrier, even an armoured British carrier, would have almost certainly inflicted fatal damage.

ABOARD TF57

TF57 was back on duty off the Sakishima Gunto later in April, and after being rotated out of the battle area for replenishment, by 4 May was off Miyako, one of the islands in the group. The carriers were especially vulnerable on this day as the battleships, capable of mounting such an intense AA barrage around them, were away shelling coastal targets on Okinawa following a request from the forces ashore. It was not long before a Kamikaze attacked HMS Formidable. It was witnessed by Geoffrey Brooke, the ship’s fire and crash officer, and his reactions were recorded in John Winton’s book, The Forgotten Fleet:

It was a grim sight. I thought at first that the Kamikaze had hit the island and those on the bridge must be killed. Fires were blazing around several piles of wreckage on deck and a lift aft of the island and clouds of dense black smoke billowed far above the ship. Much of the smoke came from fires on deck, but as much seemed to be issuing from the funnel, which gave the impression of damage deep below decks.

The carrier had been hit at 11.31 by a Kamikaze that managed to put a 2-feet dent in the flight deck, although without bursting through into the hangar. The flight deck had been crowded at the time as aircraft were being ranged ready for launching, so eight men were killed and forty-seven wounded, many of them with severe burns. It could have been even worse. The ship’s medical officer had decided to move the flight deck sick bay from the Air Intelligence Office at the base of the island where the Kamikaze had struck. As it was, two officers were killed in the AIO and the others with them all horribly burned.

Five days later, on 9 May Formidable was hit yet again, and this time the Kamikaze hit the after end of the flight deck and ploughed into aircraft ranged there. This was made even worse than it might have been, as a rivet was blown out of the deck and burning aviation fuel poured into the hangar where the fire could only be extinguished by spraying, causing damage even to those aircraft not on fire. Seven aircraft were lost on deck and another twelve in the hangar, leaving the ship with just four bombers and eleven fighters.

Worse was to come, with the nautical equivalent of an ‘own goal’ on 18 May. After having refuelled and taken on board replacement aircraft, in the hangar an armourer working on a Corsair failed to notice that the aircraft’s guns were still armed. He accidentally fired the guns into a parked Avenger, which blew up and set off another fierce fire, this time destroying thirty aircraft. Yet, the ship was operational again by that evening.

American misgivings about the Royal Navy’s state of preparedness for intensive operations in the Pacific have been mentioned earlier. The concerns were not without foundation.

Before leaving Sydney for Okinawa to replace Illustrious, many of Formidable’s ship’s company had seen a film, Fighting Lady, about an American aircraft carrier in the Pacific:

‘I came to the unpalatable conclusion that our fire-fighting equipment was totally inadequate and was shocked to discover that there was no more left in the dockyard store,’ recalls Geoffrey Brooke. ‘In some trepidation I went and bearded Captain Rocke-Keene, who, hardly looking up from his papers, said ‘‘Are you sure? Then buy some!’’ Knowing better than to ask how, I took myself off to the largest store in Sydney and asked for the fire-fighting department. To my surprise there was an excellent one, full of the latest American gear, I ordered a variety on approval, and had a field day testing them on the flight deck and invited the skipper to a demonstration of the choicest items. On completion, he said, ‘‘Come ashore with me in half-an-hour,’’ and I found myself the rather embarrassed third party to a verbal meal, with much table thumping, of the Captain of the Dockyard. By the end of it he was only too glad to get rid of us by underwriting the expenditure of many thousands of pounds.’

The pressures of the Pacific War did have a beneficial impact on operations. At one stage HMS Implacable was able to land aircraft on with an average interval between aircraft of 31.8 seconds, which required great confidence in the deck landing officer, the ‘batsman’, excellent airmanship, and well-trained and energetic deck parties, including someone who was a dab hand at raising and lowering the barrier so that aircraft that had hooked on could taxi forward to the deck park and leave the after end of the flight deck free for the next aircraft.

At the end of the Okinawa campaign, ‘Operation Iceberg’, the British Pacific Fleet, aka TF57, had been at sea for sixty-two days apart from eight days’ replenishing at Leyte. Strikes had been flown from the carriers on twenty-three days, giving a total of 4,691 sorties, dropping 927 tons of bombs and firing 950 rocket projectiles. The number of Japanese aircraft destroyed has been estimated at between seventy-five and 100, while airfields and shore installations also received attention. While twenty-six aircraft had been shot down by the enemy, another seventy-two were lost in accidents, including no less than sixty-one while landing on. Another thirty-two aircraft had been accounted for during the Kamikaze attacks, as well as the thirty lost in the wholly unnecessary fire.