Over the next few days, the deception troops would work closely with the genuine 4th Division in a series of moves to make any enemy agent think the 4th was being pulled back to Camp Elsenborn. The 4th Division made sure that during the upcoming move every bumper marking, helmet insignia, and shoulder patch was hidden. To assist in the shift north, the 4th Division was to use the code name RED WING. Combat elements were to move only at night, while the support units were to move during the day in a strictly controlled fashion. Some groups would travel in a standard column while others would move individually with roughly two-minute intervals between them.

Men assigned as road guides, to be left at key junctions along the route to direct traffic, were ordered to put a four-inch cross of one-inch white tape on their helmets for increased visibility. At night, traffic was directed by using a flashlight with half of the lens covered by a blue filter and half by a red filter.

Signs directing the way were to bear no relation to what was normally used by the 4th Division. A new system of signage was created, based on a cross with a symbol in one of the four quadrants. A mark in the upper right quadrant indicated the route for the 8th Regiment, the lower left quadrant for the 22nd Regiment, and all other troops used a specific letter in the upper left quadrant. (M was for the division command post, J for the 70th Tank Battalion, B for the 4th Medical Battalion, and so on.)

While preparing for the mission, the 23rd troops discovered that trying to hide their bumper markings with mud was not practical. This tended to smear the fresh paint. The solution was to use canvas bumper covers to hide the markings. The men, however, then discovered that wet roads caused the tape used to hold the covers in place to loosen and fall off. Finally the men learned to use wire or string to tie the covers in place until the time came to remove them.

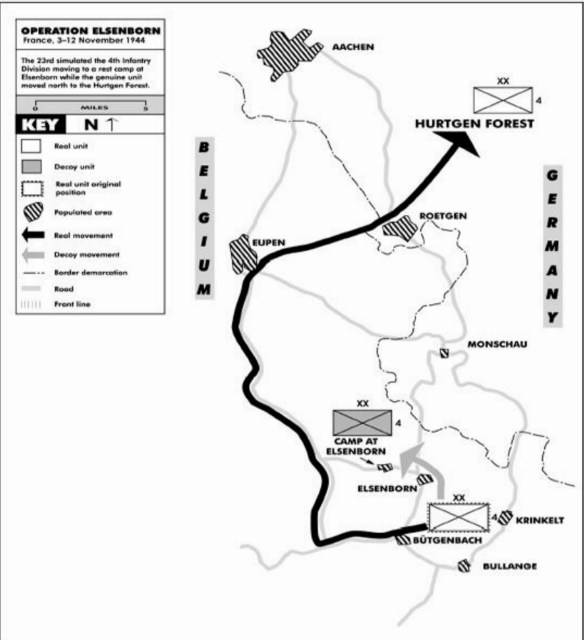

On 6 November, a detachment of deception troops in fifteen vehicles infiltrated into the 4th Division Command Post area. There they assumed the guise of the 4th Division headquarters. While a great show was made of the newly formed 4th Division convoy heading to Elsenborn, the genuine vehicles of the divisional headquarters made their way via a circuitous route north to an assembly area behind the Hurtgen Forest.

The following day, another group of fifteen vehicles quietly entered the 8th Infantry Regiment area and took on the appearance of a convoy from that unit. They headed back to Camp Elsenborn while the genuine 8th, with their identity concealed, headed north. On 8 November, twenty-three vehicles assumed the guise of a convoy containing troops from the 22nd Regiment, 44th Field Artillery Battalion, plus the 4th Engineers, and made the journey to their assigned area in Camp Elsenborn. They shared the road with another convoy of eight vehicles playing the role of the 4th Quartermaster Company. The move was marred only by a road accident that demolished one of the message center vehicles. No one was hurt, but an appropriate show was made to make sure anyone watching could see that the wrecked vehicle was from the 4th Division.

One of the 4th Division men making the secretive journey north was Lieutenant George Wilson from the 22nd Infantry Regiment. As he recalled, “Long after darkness on about November 10, 1944, the 4th Division leapfrogged some thirty miles further north along the German–Belgian border. This was to be a highly secret maneuver, so elaborate that pains were taken to erase all signs of our identity. Divisional and regimental numbers were blocked out on all vehicles, and the green, four-leafed ivy shoulder patches, of which we were so proud, were removed from our uniforms… . Our blacked-out trucks took long confusing detours to the rear to mislead enemy agents.”

Once the notional convoys arrived at Camp Elsenborn, they were directed to the area of the camp where they were to set up a display of the unit at rest. On the night of 9 November it began snowing, which added an extra element of difficulty to the operation. Just driving vehicles around the area became increasingly difficult as the military tires were designed for off-road use and provided little traction on a slippery road. Chains had to be put on to increase traction, and the men hoped that the noise made by the chains added a new element of reality to their show.

Once the notional convoys had arrived in the camp they were directed to set up operations in their assigned buildings. Signs and sentries were posted in a manner similar to what the 9th Division had used during their stay there. Roving patrols of MPs moved about the camp and surrounding area. Signs bearing the name CACTUS (the code name of the 4th Division) were prominently displayed around the same building where the 9th had based its headquarters.

Military police posts were stationed in neighboring towns and manned night and day. Two jeeps marked as 4th Division MP vehicles were used to bring food to the posts and patrol the area. Water points continued to operate in the manner used by the 9th Division, but with 4th Division–marked personnel. Anyone observing their actions would see water being drawn for a full division, less the one combat team.

Vehicles were sent out in a pattern based on that previously observed. On the recommendation of the 4th Division, these movements were made by trucks marked according to individual regiments and battalions, since the quartermaster trucks of the genuine 4th Division were badly in need of maintenance. Messenger vehicles, wire patrols, and mail trucks made their rounds so as to conform to the normal practices of the 4th Division. Other trucks made runs to the garbage disposal point, shower point, and ration depot.

This did not always entail a large number of vehicles. On 10 November, the special effects section noted that the following vehicles were sent outside the camp: at 1000 one 2½-ton truck to the water point, 1000 one jeep sent to Malmedy, 1100 one truck sent to the ration depot, 1350 two trucks sent to nearby towns, and at 1500 one truck sent to the garbage disposal point. From 1300 to 1600 vehicles drove about the camp area to lay new tracks in the snow. This was done in the late afternoon so they would be ready for any German aircraft making a twilight reconnaissance run.

The snow posed an additional problem because an enemy agent could see from the tracks that only a few vehicles had actually passed by. Trucks were sent out specifically to increase the number of tracks in the snow. This would not only deceive an agent watching the roads, but also any German observation aircraft looking for activity in the area. A regimental headquarters was set up in the town of Elsenborn, properly marked as a 4th Division unit.

Most of the local population had been evacuated from the area before the operation, and the snow and cold weather kept the remaining few indoors most of the time. However, a number of American soldiers looking to visit friends in the 4th Division turned up at the notional divisional HQ, and a handful of men from the genuine 4th trying to find their unit ended up at the camp, totally confused by the familiar signs but the unfamiliar faces.

The display of a division at rest was slowly built up over three days as the new notional convoys arrived. Left out of the display were all the elements that had gone with the 12th Regiment to the Hurtgen. It would not do to try and simulate a unit that was already fighting in the front lines.

There was some confusion on 10 November when an advance party of the 9th Infantry Division arrived at the camp to prepare for their division’s move back. The camp could not house two divisions at once, so the return of the 9th would indicate that it had all been a deception. Calm heads prevailed, and it was eventually decided that the 23rd would shift their activities and signs to another area of the camp while the 9th prepared to move in.

Finally, at 1800 on 11 November, the word was received that the operation would end the following day and the 9th Division would once again take over the camp. All visual aspects of the 4th Division were slowly dismantled that night. Starting at 1000 the following morning, the now unmarked vehicles of the 23rd began infiltrating out of the camp, at three-minute intervals, heading back to Luxembourg City.

The radio aspect of the deception had gone off without any problems. It had been carefully planned out, so everyone knew exactly what he was supposed to do. To keep the radio aspects of the deception from standing out, the next unit to arrive at the camp, the 99th Infantry Division, was also requested to transmit radio proficiency test messages. This would also allow the Americans to use the same ruse of a radio test in a rest camp for any future operations without drawing attention to it.

Overall, the staff at the V Corps and 12th Army Group were happy with the operation. It was claimed in the 23rd’s records that a German intelligence document was captured shortly afterward indicating that the 4th was still in Camp Elsenborn. George Wilson, of the 22nd Infantry Regiment, however, recalled that the 4th Division had been welcomed to the Hurtgen Forest by Axis Sally, the German radio propaganda broadcaster, when they entered the area. This could indicate the operation was a failure, but also could have been only hearsay information obtained from other troops, or, more likely, a reference to the 12th Infantry Regiment that had previously been fighting in the forest. Thus a well-performed deception might have been ruined by the necessity to send part of the division on ahead. There is little use in trying to hide the movement of a unit if part of it has already been sent on ahead.

One of the lessons learned was that the 23rd could pull off appearing as a division in an enclosed rest area, but the officers realized that they could not have pulled off the same deception if the division had been bivouacked in a less controlled or more open area, due to the lack of men and vehicles. Nevertheless, everyone was very happy with the cooperation they had gotten at every level. The 4th Division’s quartermasters had happily handed over a supply of divisional patches when asked, and the 23rd’s signalmen had no trouble obtaining any information they requested.

This time, the problem of men looking for their friends had been anticipated. Anyone who came to the notional 4th Division area looking for someone was told that, while most of the division was in the camp, that specific unit was located elsewhere. This worked, with the exception of one time when a soldier came looking for his brother in the 4th MP Platoon. Since he was asking men dressed as 4th Division MPs, they could not claim the unit was elsewhere. At first they replied, “Never heard of him.” “Why, he’s your cook, you must know him,” argued the brother. The quick thinking MP replied, “Oh, you must mean ‘stinky.’ I didn’t recognize the name. Sure I know him. He just moved out with a bunch that went north.” On another occasion, a 23rd man replied that the reason he did not know many others in his unit was that he had been wounded in the infantry and had just arrived as a replacement.