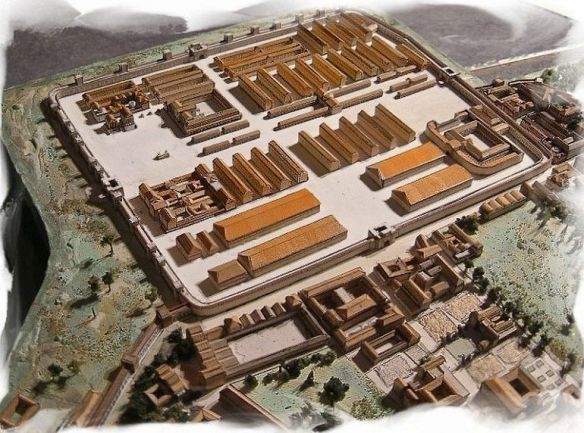

More like a fortress than a camp, the Castra Praetoria (or Praetorian Camp) was constructed in 23 AD by Lucius Aelius Sejanus. Erected just outside the perimeters of Rome, the fort boasted solid masonry walls made of concrete with red-brick facing. It encompassed an area of over 17 hectares (1,440 ft × 1,250 ft). And while based on just the area the fort could house around 4,000 troops, archaeologists have revealed the remnants of two-floored barrack structures and extra rooms arrayed around the inside of the walls. These combined spatial elements could have actually accounted for double or triple that number.

Otho was struggling with leading an army. He was disorientated by the way his troops criticized his senatorial generals, Annius Gallus, Suetonius Paulinus and Marius Celsus, with those responsible for Galba’s murder being the most disruptive. Otho handed over command to his brother Salvius Titianus. However, more positive news lay ahead. Caecina, infuriated by his humiliation at Placentia, was bent on recovering his reputation. At a place called the Castores, a shrine site 12 miles (19 km) from Bedriacum, he set up an ambush and laid plans to entice the Othonian forces into it. Unfortunately, someone in Caecina’s army passed the information on to the Othonians. Paulinus and Celsus prepared for the battle by using a combination of legionaries, auxiliaries, praetorians and praetorian cavalry. Three praetorian cohorts were to hold the road, and a force of a thousand cavalry drawn from praetorians and auxiliaries was organized to mop up at the end of the battle.

To begin with the battle did not go too well for the Othonians. Part of the praetorian cavalry was wiped out when the Vitellians counter-attacked from the safety of a wood. This setback was rapidly overcome when the main Othonian infantry force charged and routed the Vitellians. In the aftermath, though, the Vitellian armies’ prospects improved when Fabius Valens and his force joined up with Caecina. There was now a risk that the combined Vitellians would attack quickly. Otho sought advice from his generals. Paulinus, supported by Celsus and Gallus, counselled waiting because the Vitellians were likely to be undone by supply problems as they made their way into Italy. The Vitellian forces could not count on the rest of Britain’s huge garrison crossing over to join them since the province was proving so troublesome to keep under control. Conversely, the Othonian army had plenty of resources and still held Rome.

Otho was more inclined to listen to his brother Titianus and the praetorian prefect Proculus. They recommended going for an attack on the basis that luck and the gods were on Otho’s side. Otho, preferring superstition to reason, decided to attack but also accepted a decision that it was too dangerous for him to stay. He was to withdraw to Brixellum (Bresello). It was a fateful decision. Otho set out with ‘cohorts of praetorians and speculatores, and some cavalry’, but his departure demoralized the troops who were left behind. None of this escaped the notice of Valens and Caecina. Tacitus raised the possibility that the two forces toyed with the idea of negotiating a peace rather than fighting it out for two men, each of whom was so obviously unsuitable for power. But Tacitus also rejected that theory as implausible on the basis that as the Roman world had grown stronger so the thirst for power won by violence had superseded anything else.

Either way, the war continued. The Othonians were now commanded by Titianus and controlled by the praetorian prefect Proculus. The tribunes leading two of the Othonian praetorian cohorts left on campaign made their way over to enemy territory and tried to speak to Caecina. Before they could explain what they wanted, whether to sue for peace, to go over to Caecina or initiate some ruse to trick him, he was warned by his own lookouts that the Othonians were approaching. Caecina returned to the main force where Fabius Valens was preparing for battle. The fight that followed near the city of Bedriacum (Cividale) on 14 April 69 was bloody and chaotic, but the Vitellians prevailed. It is known to history as the First Battle of Bedriacum, or the First Battle of Cremona. The Othonian praetorians vented their fury by blaming the defeat on treachery, almost certainly a reference to what Tacitus described as hand-to-hand fighting between troops who had known each other. This must have been the praetorians, and I legion Italica, both of which were based in Italy. The news filtered through to Otho at Brixellum; it had been a comprehensive disaster. Otho’s supporters tried to bolster his resolve. The praetorian prefect Plotius Firmus begged him to stand fast in the face of adversity, and was backed up by other soldiers who insisted that reinforcements were on their way. Otho, however, recognized that the game was up and the price of carrying on too much. He settled his affairs and arranged for his inner circle of friends and attendants to be transported away. Despite his calm and collected approach, Otho still had to settle down his troops who were threatening to kill his staff as they left.

At dawn on 16 April 69 Otho committed suicide. It was an honourable death that went some way to ameliorating his tarnished reputation. Praetorians carried the body to the funeral pyre, some remarkably even choosing to take their own lives too, so impressed had they been by his dignified end. At least the praetorians showed an appropriate level of loyalty, having brought Otho into power and continuing to hold him in high esteem. In the event his reign had lasted only into its ninety-fifth day, or just over three months. Once more, the Praetorian Guard was without an emperor. Soon there would be no Othonian Praetorian Guard at all.

Vitellius, at this juncture, had no idea that he was effectively emperor of the whole Roman world. He expended most of his efforts on preparing for more fighting with Otho’s forces, completely unaware that this was unnecessary. The impact of the previous fighting had been bad enough on civilian communities in Italy but now his troops in Italy simply capitalized on the opportunity to run riot, sacking rich villa estates. When Vitellius learned of what had happened to Otho his reaction was a mixture of magnanimity and revenge. He met his supporters and former enemies at Lyon. He executed Otho’s principal centurions, which immediately alienated some of the army, but acquitted Suetonius Paulinus and observed proper legality when it came to the wills of Otho’s deceased supporters. Tacitus indulged himself with a depiction of Vitellius as an otiose and repellent glutton who was far more concerned with rich food and luxuries than with disciplining and organizing his forces The regime appears to have become more brutal in fairly short order, with summary and arbitrary executions.

One of Vitellius’ problems was how to deal with Otho’s legions, now thoroughly resentful at the humiliation of defeat. The soldiers of the XIIII legion Gemina Martia Victrix, a unit with a significant military reputation after its defeat of Boudica in Britain in 60–1, were very embittered and even insisted that most of them had not been at Bedriacum. So, therefore, technically the legion had not been defeated. Vitellius ordered them to return to Britain but until the transfer went ahead they were stationed in the Augusta Taurinorum (Turin) area with some auxiliary Batavian cohorts. This was an exceptionally bad decision since the Batavians and the legionaries loathed each other. A fight broke out when a legionary backed a local civilian whom a Batavian said he had been cheated by. The violence was set to get a great deal worse except that two praetorian cohorts, presumably also billeted nearby, joined in on the side of the legionaries and forced the Batavians to back off.

This incident demonstrates that Othonian praetorians were still operating alongside the rest of the defeated army, and also capable of dangerous partisanship. Vitellius’ solution was two-fold. Firstly, the men were ‘separated’, which could either mean that they were now to be kept apart from the rest of the army or that the individual praetorian cohorts were now dispersed so that they could not act together. Secondly, Vitellius offered them an honourable discharge, which in practice amounted to presenting them with the opportunity to end their service early on the same terms as if they had completed their full sixteen years. Suetonius suggests that the process was more punitive, saying that Vitellius disbanded the Othonian praetorians by edict on the grounds that they had treacherously abandoned Galba for Otho. In addition, he ordered that one hundred and twenty praetorians who had requested a reward from Otho for helping to murder Galba be hunted down and punished. This was not wholly unreasonable and, indeed, Suetonius considered it a responsible act since it was quite plain the Othonian praetorians had acted without honour in abandoning and killing one emperor in favour of another. Either way, the demobilization of the Othonian praetorians started out well from Vitellius’ perspective, since the praetorians had clearly not transferred their loyalty to him, though his failure to secure their loyalty would play a crucial part in his downfall. The demobilization process started with praetorians handing over their equipment to the tribunes and preparing for retirement, but this simply provided Vespasian with an opportunity. Unfortunately for Vitellius, news started to reach the dismissed praetorians that Vespasian in the east was commencing his own bid for power.

Titus Flavius Vespasianus had been sent out to the east in 66 by Nero to settle the Jewish Revolt with his son Titus. A tough and experienced general, Vespasian had played a major role in the invasion of Britain in 43, commanding the II Augusta. He took over the campaign against the Jews from the governor of Syria, Gaius Licinius Mucianus, but the two remained important allies, though Mucianus was even keener on Titus. Mucianus played a crucial role in persuading Vespasian to challenge Vitellius. On 1 July 69 in Alexandria, Vespasian was declared emperor with the assistance of the prefect of Egypt, Tiberius Julius Alexander, who obligingly organized his garrison to take the oath of allegiance. When the news reached Syria, Mucianus had his troops take the oath too. By 15 July 69 the whole of the wealthy province of Syria was behind Vespasian, with Asia, Greece and other important provinces onside. However, apart from Syria, not all these places had garrisons so it was crucial for Vespasian to bring over as much of the Roman armed forces as possible. Vespasian prepared extremely carefully. He started by striking his own bullion coinage at Antioch so that he could pay his forces and offer rank and position to men who came over to him. He also secured the Empire’s eastern borders so that his campaign could proceed without placing the eastern provinces in danger from Armenia and Parthia. Titus would finish the war against the Jews. Vespasian would settle affairs in the east, securing Egypt so that he could starve out Vitellius, and Mucianus would march against Vitellius. Vespasian made a particular point of targeting the praetorians whom he knew were hostile to Vitellius. He wrote to all the various Roman armies he could, requesting that they encourage the praetorians to come over to him, dangling the carrot of readmission to the Praetorian Guard.

In the meantime Vitellius marched towards Rome with an army of sixty thousand men, Vitellian senators and equestrians, hangers-on and entertainers. Like a plague of locusts this motley crew made its way through Italy, taking whatever it needed from the hapless communities unfortunate enough to lie in the way. Eventually, the Vitellian entourage reached Rome but his advisers had the wit to discourage Vitellius from marching in as if he were a conquering general. He donned a toga for his big moment, but was still followed in by his forces. Tacitus conceded that it was a very impressive moment, or, rather, would have been, had it not involved Vitellius.

Now safely ensconced in Rome, Vitellius adopted the trappings of an emperor. He accepted the title Augustus, became pontifex maximus (chief priest), and attended the senate, though it appears that the two men really running the show were Valens and Caecina. Vitellius also chose two prefects to command the Praetorian Guard, though at that point there were no Vitellian praetorians to command. Vitellius selected two associates of Valens and Caecina respectively, a centurion called Julius Priscus and a prefect of an auxiliary cohort called Publilius Sabinus. Valens and Caecina were increasingly preoccupied with their own rivalry, so the praetorian prefectures are best seen as an extension of that tension. Rome was already in a dangerous state. Since Vitellius had brought sixty thousand troops with him it was patently clear that the Castra Praetoria could not possibly accommodate them, so they ranged dangerously through the city without any semblance of discipline or organization.

In the event, sixteen milliary praetorian cohorts were formed by Valens on Vitellius’ behalf, along with four urban cohorts, using soldiers taken from Vitellius’ legions. It is quite possible, as was discussed earlier, that this was already the size of the praetorian cohorts. If so, then the principal point of interest is the increase from twelve to sixteen praetorian cohorts, taking the Guard at least from twelve to sixteen thousand men. If the praetorian cohorts had only been quingenary up to this date then the increase was even more dramatic. Quantity was more important to Vitellius than quality. He allowed soldiers to choose the unit in which they wished to serve, regardless of their personal attributes or motivation. The result was that the new Vitellian praetorians included disreputable individuals and damaged the Guard’s prestige.

There were now effectively two groups of praetorians: Vitellius’ sixteen thousand new praetorians recruited from his legions, and Otho’s old (and now discharged) praetorians. In the context of the chaos at Rome, Vitellius’ profligacy and the attractive prospect of Vespasian, the Vitellian supporters started to drift away. It began with the III legion, which went over to Vespasian. Vitellius dismissed the reports in a speech to his forces, blaming the discharged Othonian praetorians for spreading rumours of civil war. Other commanders waited to see which way the tide would turn. By September 69 the game was nearly up for Vitellius. The first wave of Flavian forces, under Antonius Primus, reached northern Italy, ready to secure the Alps and open the way in to the peninsula for Mucianus, then following up from the rear. Vitellius ordered Valens and Caecina to march north to meet them, which they did, setting out for Bedriacum. Caecina decided to betray Vitellius. His associate was the disaffected Lucilius Bassus, commander of the Vitellian fleets at Ravenna and Misenum. Despite this prestigious command, Bassus was embittered that he had not been made praetorian prefect. Bassus then turned the fleet over to Vespasian, and would have been followed by Caecina had the latter not been imprisoned by his own soldiers.

The Second Battle of Bedriacum (Cremona) followed shortly afterwards on 24 October 69. The old praetorians fought alongside the III legion for the Flavians where they would help play a crucial role. The battle did not start well for the Flavian forces and Antonius Primus was forced to call them up to help hold his line. Even so, Vitellian artillery proved extremely dangerous to the Flavian forces. A Vitellian ballista belonging to the XV legion proved particularly lethal. Two soldiers, possibly praetorians, dashed forward, disguising themselves by picking up shields from dead legionaries of the XV, and wrecked the machine by cutting its ropes. Obviously that gave the two men away and they were killed immediately by the Vitellians. Their heroic effort seems to have gone down in Roman military lore even though their names remained unknown. If they were praetorians then the episode suggests that in battle they were otherwise indistinguishable from legionaries. Primus spoke to all his forces, selecting the praetorians for special treatment when he said that if they did not win that day then there was no one else who would have them. When the III legion hailed the sunrise this kicked off a rumour that Mucianus had arrived to reinforce the Flavians. This was not true but the Flavians were galvanized and rallied. The Vitellians collapsed and the Flavians had the day. A horrific sack of Cremona followed, lasting four days, in revenge for the city’s support for Vitellius.

In Rome, Vitellius was understandably disorientated by events. He sent Valens off to fight at the front and turned on one of his praetorian prefects, Publilius Sabinus, because he had been Caecina’s nominee. In his place Alfenus Varus, an ally of Valens, was appointed. The Vitellian praetorians might now have played an important role in helping bolster Valens in the war; indeed, this was mooted, but he rejected the plan. Perhaps he knew they were not up to the job. Valens went to the province of Alpes Maritimae (Maritime Alps) where the procurator, Marius Maturus, warned him not to head into neighbouring Gallia Narbonensis. At this point Valerius Paulinus, procurator of Gallia Narbonensis and a supporter of Vespasian, weighed in. He had called up the old praetorians whom Vitellius had discharged, cashing in on his popularity with them since he had once been a tribune of the Guard, and stationing them in Forum Julii (Fréjus). Valens had to leave, taking with him just four speculatores from the Maritime Alps but, thanks to a storm, was washed up on some islands near Toulon and captured by a force sent after him by Valerius Paulinus. He was subsequently executed on or around 10 December 69.

In another passage Tacitus mused on the extent to which chance, rather than fate and circumstance, dictated events. Valens’ end could not have been a better example. The chance storm that washed Valens up on the ÎlIes d’Hyères meant that, for him, the war was over. With Valens removed, the whole Vitellian edifice started to collapse. The process was not instant, nor was it straightforward, but it was relentless. The legions gradually began to tranfer their allegiance to Vespasian. Nevertheless, Vitellius had not yet given up, though he seems to have been a man inclined to change his mind; one of his habits was to dismiss the praetorians and then promptly call them back again. Antonius Primus made his way into Italy, slightly concerned to hear a rumour that Vitellian praetorians had been sent north from Rome to meet them. In fact Vitellius had sent almost twenty thousand troops in the form of fourteen of his praetorian cohorts and a legion’s worth of naval troops under the command of Julius Priscus and Alfenus Varus. The remaining two praetorian cohorts and, presumably, the urban cohorts were left behind to protect Rome under the command of Vitellius’ brother, Lucius. Vitellius then headed off to his army in the field at Mevania (Bevagna in Umbria), in spite of his lack of experience as a military commander.

News arrived that the Misenum fleet had abandoned Vitellius. The reason was sheer trickery. A Flavian sympathizer, a centurion called Claudius Faventinus, circulated a forged letter which he claimed had been sent by Vespasian. The ‘letter’ offered the fleet a reward in exchange for abandoning Vitellius. In the ensuing confusion the Campanian cities of Puteoli and Capua became involved, the latter being pro-Vitellian but not for long. Capua went over to Vespasian too and the rebel forces ended up taking control of Tarracina. Vitellius divided his forces. He ordered Priscus and Alfenus Varus to stay at Narnia with, presumably, eight praetorian cohorts, and sent his brother Lucius with the remaining six cohorts and five hundred cavalry to deal with the Campanian threat. The onset of winter was a distinct advantage to Vitellius, but the Flavians also had luck on their side. They were joined by the general Petilius Cerealis, who had managed to find his way to them disguised as a peasant.

At Interamna (Terni) a Vitellian force of four hundred cavalry was garrisoning the city. A Flavian force under Arrius Antoninus Varus, Antonius Primus’ cavalry commander, attacked them but most immediately surrendered. A few got away and headed back to the main Vitellian army where they bewailed the size of the Flavian force in order to explain their defeat. The praetorian prefects Julius Priscus and Alfenus Varus immediately left to go to Vitellius. That had the effect of persuading the rest of the Vitellian force that there was no shame in giving up. As the Vitellian cause collapsed, the Flavian forces under Antonius Primus and Antoninus Varus offered Vitellius his life in return for capitulating to Vespasian, though this was really a hopelessly unrealistic prospect. It was an offer Vitellius considered but while he was doing so Rome was about to fall to Vespasian. The prefect of Rome was Titus Flavius Sabinus, elder brother of Vespasian. Senior senators assured Sabinus of their support, and pointed out that with the urban cohorts and the night watch at his disposal, it would be easy to bring Rome over and win credit for helping to end the war.

On 18 December 69, Vitellius abdicated. He said it was in the interests of peace. Sabinus, with whom Vitellius had been negotiating, sent instructions to ‘the tribunes of the cohorts’ to keep the men in their barracks. This may or not be referring at least in part to the tribunes of such praetorians who were still in Rome. Unfortunately for Sabinus and the Flavian supporters amongst the senators and equestrians, the general public in Rome was still distinctly pro-Vitellian and a fight broke out between them and Sabinus’ forces. Sabinus, angry that the agreement with Vitellius had broken down, took the Capitol with his men. Here he was joined by Vespasian’s younger son, Domitian. In the ensuing fight, the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus was burnt down. The Vitellians captured the Capitol. Domitian escaped but Sabinus was captured and brutally murdered. This was an enormous shock to the Flavian army, now at the city of Ocriculum (Otricoli), just 44 miles (71 km) north of Rome. More bad news followed when it turned out that Petilius Cerealis and a cavalry force had been defeated in the city suburbs.

Despite these setbacks, an attempt by the Vitellians to negotiate peace collapsed. On 20 December 69, the Flavian army entered Rome and an orgy of violence followed, climaxing in the battle for control of the Castra Praetoria, which Vitellians were determined to hold as their last stand. Since the Flavian army included former praetorians who were determined to recover the barracks from the usurpers, the fighting was all the more vicious. The Flavians organized themselves into the testudo formation and brought up artillery to assault the Castra Praetoria. When the camp fell, it did so with dead Vitellians hanging over the walls and those left alive charging the attackers in a last and futile gesture of defiance. The fall of the Castra Praetoria was the climax of the fighting and its collapse marked the end of the reign of Vitellius. He planned an escape but was apprehended by a tribune called Julius Placidus, only to be attacked by soldiers from the German garrison who killed him on the Gemonian Stairs. Vitellius’ reign of nine months had ended in a cavalcade of destructive violence that had torn the Roman Empire apart. Throughout those desperate months the praetorians, on whichever side, had played important roles, but it was the way in which the Castra Praetoria, yet again, acted as the stage on which so much of the drama unfolded that epitomized the importance of the imperial bodyguard to Roman history.