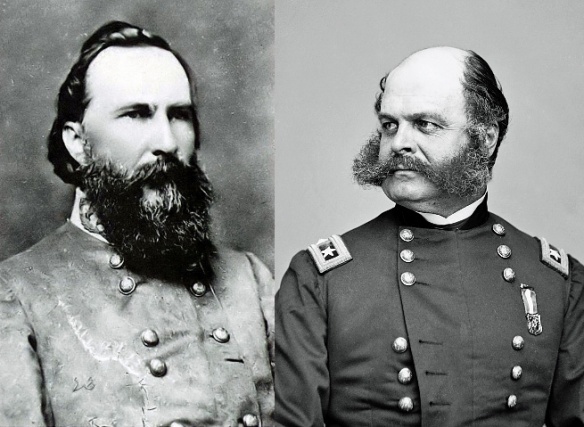

James Longstreet and Ambrose Burnside, principal commanders of the Knoxville Campaign.

Knoxville was the major city of eastern Tennessee, the mountainous region for which Lincoln felt such concern as it was the centre of Union sentiment inside the Confederacy. From the beginning of the war, he was anxious to bring it under Federal control, and throughout 1862-63 he urged a succession of Union commanders to move against it. In March 1863 General Ambrose Burnside, who had been so heavily defeated at Fredericksburg the previous December, was transferred to the West. He was ordered to move against Knoxville as quickly as possible, while General William Rosecrans was ordered to operate against Braxton Bragg in what became the Tullahoma campaign. Burnside commanded the Army of the Ohio, Rosecrans the Army of the Cumberland.

Burnside intended to advance from Cincinnati with two corps, the Ninth and the Twenty-third, but lost the Ninth when it was given to Grant for the campaign against Vicksburg. While awaiting the return of the Ninth Corps, Burnside sent a brigade and some cavalry to advance on Knoxville. During June, this force, led by General William Sanders, destroyed railroads around the city, where General Simon Buckner was in command.

In August Burnside began his advance on Knoxville. His direct route ran through the Cumberland Gap, heavily defended by the Confederates. To avoid them Burnside made a flank movement to the south, by forced marches through the broken country. As the Chickamauga campaign began, Buckner was ordered to take most of his troops to join Bragg at Chattanooga and was left with only two brigades, one in the Cumberland Gap, on the northeastern border of the state, and another east of Knoxville. In these circumstances Burnside pressed forward and was able to send a cavalry brigade into Knoxville on September 2. It was unopposed and found the city empty of rebel troops. He was enthusiastically welcomed by the loyal population. Burnside arrived with his army the next day.

He then set about dealing with the Confederates at the Cumberland Gap in order to open up a more direct route to Kentucky. He had two forces in position to confront the new Confederate commander, General John Frazer; though outnumbered, Frazer refused to surrender. Burnside then led a brigade from Knoxville to the gap, making a march of sixty miles in fifty-two hours. On his arrival, Frazer, accepting that he was hopelessly outnumbered, surrendered on September 9. Burnside recruited new units of Tennessee volunteers and set about clearing the roads and gaps leading northward towards Virginia. Meanwhile, Grant, who had now captured Chattanooga, was preparing to fight at Chickamauga, to which Lincoln and Halleck ordered Burnside to detach troops in order to support Rosecrans, who was in difficulty. But, unwilling to surrender Knoxville, Burnside procrastinated; he was having difficulty supplying his troops in the desolate country to the east of Knoxville. During September and early October he was forced to fight two small battles, at Blountsville and Blue Springs, both minor victories, which led to the reestablishment of Union authority in eastern Tennessee.

Braxton Bragg, fearing that Burnside might reinforce the Union troops at Chattanooga, asked Jefferson Davis to order Longstreet to concentrate against him. Longstreet objected, knowing he would be severely outnumbered, since large Union reinforcements were approaching Chattanooga to add to the imbalance. He also objected to the division of force involved, which, he said, would expose both Confederate commanders to defeat. He therefore resumed his preparations to move against Knoxville. The move was to be made by rail, but the journey proved difficult. The trains did not arrive on time, so that the advance had to begin on foot. When the trains did arrive, the locomotives proved underpowered, forcing the troops to dismount on the steeper gradients. They also had to collect wood for the engines. Food ran short. Longstreet’s advance nevertheless cheered Lincoln, who, having previously told Burnside to leave Knoxville, now ordered him to stay and defend the city. Grant prepared to send reinforcements from Chattanooga, but Burnside now convinced him that he could detach sufficient troops to hold Longstreet at a distance. Grant willingly concurred. Next the Confederates attempted to encircle Knoxville with cavalry, but Union resistance thwarted their plan and the cavalry joined Longstreet in the north. Burnside manoeuvred outside the city and successfully reached a vital crossroads. Burnside won a brisk minor victory at this point, Campbell’s Station, which allowed him to withdraw his strength inside Knoxville. On November 17 Longstreet laid siege. His assault on the defences was delayed, and Longstreet took advantage of the opportunity to strengthen his earthworks. Longstreet eventually attacked a week after the siege had begun, at a point he judged weak, Fort Sanders, but which was deceptively strong. The Union had surrounded the earthworks with a network of telegraph wire strung between trees. The Confederate attack launched on November 29, 1863, was effectively checked by the defences and Union covering fire. There were 813 Confederate losses, only 13 Union.

The defeated Longstreet considered his options. He had been ordered to join Bragg, who had just been defeated at Missionary Ridge on November 25. He felt that move impracticable and told Bragg that he would withdraw with the Army of Tennessee to Virginia, but would keep up the siege of Knoxville as long as possible, to prevent Grant and Burnside concentrating against him. Longstreet’s stubbornness had the effect of causing Grant to send Sherman with 25,000 men to raise the siege of Knoxville. Longstreet accordingly abandoned the siege on December 4 and retired northwards to Rogersville, Tennessee, where he prepared to go into winter quarters. Sherman left part of his force at Knoxville and took the rest back to Chattanooga. General John Parke, Burnside’s chief of staff, pursued the retreating Confederates with 8,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry, though he did not press the pace. Longstreet’s route took him through Rutledge and Rogersville, followed by General John Shackelford with 4,000 cavalry and infantry. On December 9, he was near Bean’s Station when Longstreet decided to turn and attack. The Confederates got Shackelford in a pincer movement but the Union troops defended so stoutly that they repelled all Confederate attacks until reinforcements joined in. Shackelford was then forced to withdraw to Blain’s Crossroads. Longstreet followed but declined to attack their entrenchments. Both sides withdrew and left the area to go into winter quarters. Longstreet, who blamed subordinates for his failures in the campaign, asked to be relieved of command but was refused. His troops suffered in a severe winter, and he was unable to return to Virginia until the spring. His reputation and self-confidence were damaged by the campaign, while Burnside’s reputation was restored. The campaign of Knoxville, together with Grant’s victory at Chattanooga, returned eastern Tennessee to Union control for the rest of the war.

The battles of Chattanooga, Knoxville, Lookout Mountain, and Missionary Ridge had now altered the balance of advantage in Tennessee very much in the Union’s favour. With Rosecrans in strength at Chattanooga, Burnside operating in upper eastern Tennessee, and Grant free to strike in several directions from Tennessee eastward or southward, Lincoln’s long-cherished ambition, to liberate Unionist Tennessee from the Confederacy, could be safely regarded as achieved. Grant, as overall commander in the western theatre, was now at liberty to propose, if he so chose, a broad strategy for the Union’s conduct of the war in the western theatre. In the spring of 1864 he did so choose. Grant did not affect to be a high-level strategic thinker. Nothing in his manner or appearance suggested that he was anything but a commonsense, down-to-earth fighting soldier. Common sense and down-to-earthness are among the most valuable qualities, however, that a strategist can possess and he possessed them in abundance. What is valuable to those who interest themselves in his career is that in his Personal Memoirs he describes with engaging frankness how he formed his way of thinking. Grant also preferred to attack, if possible. He was not a “wait and see,” but a “go and see” general, as his conduct after Chattanooga showed. He then decided to lay plans before Lincoln for the next stage of the campaign in the West. He may have done so because he had at his headquarters a “special commissioner” from Washington, Charles Dana, formerly of the New York Tribune. Dana had been sent partly because a trickle of unflattering reports about Grant continued to reach Washington about his bad habits and Lincoln, who already wanted to promote Grant, sought his own source of information. Grant used Dana as a messenger to take his ideas for the West to Washington. He proposed leaving a reduced Army of the Tennessee to watch Bragg and to take the largest part down the Mississippi to New Orleans and then via the Gulf of Mexico to Mobile, Alabama, whence he would strike at important points in Alabama and Georgia. He had proposed such a scheme before and continued to believe in it. Those in power in Washington, however, did not. Lincoln, Halleck, and Stanton feared that if Grant’s force was moved so far away, the rebels would reawaken the war in eastern Tennessee. Communication with Washington had the result, however, of involving Grant in highlevel strategic discussion. Halleck explained to Grant that the president’s anxieties in the West remained fixed on Tennessee and its Unionists, and that before any move was made elsewhere he wanted the surviving Confederate forces in Tennessee chased down and defeated; he also wanted the Confederate army in southern Georgia pushed far enough away from the Tennessee border to ensure that it could not intervene in the state; only when those things had been achieved would he consider approving wider operations in the West.

Grant’s plan for an operation against Mobile was—surprisingly, given how clearly Grant thought—not a sound one. The Union lacked the troops in the West to mount two large operations at the same time. It could not move on Mobile and yet continue to menace the Confederates in Georgia. To attempt to find the necessary troops would inevitably result in weakening the position around Chattanooga and so encourage Johnston to strike into Tennessee. Chattanooga was that rare thing in strategy, a genuinely critical point. Held by the Union, it allowed the retention of Tennessee and the menacing of Georgia. Should it pass back into Confederate possession, Tennessee would be lost and so would the future dominance of Georgia. Halleck wrote to Grant vetoing the plan, on the grounds that the president would not approve it, a perfectly legitimate thing for Halleck to say, so perfectly did he understand Lincoln’s mind.

Later in January 1864, Grant wrote again to Halleck outlining a plan for the next stage of operations in the East. He proposed abandoning the direct advance upon Richmond for an indirect approach. The navy should embark 60,000 troops of the Army of the Potomac and land them on the coast of North Carolina, whence they could march to sever the Confederate capital’s rail connection with the Lower South and so force Lee to abandon Richmond. Halleck answered Grant as he had done earlier in January: Lincoln would not approve, since the scheme would encourage Lee to move in force against any Union army in the Carolinas; moreover, it would weaken the defences of Washington. He pointed out to Grant that his scheme contained no plan to fight Lee’s army, which should be the proper object of an eastern strategy, and was the president’s favoured aim. The best way to defeat Lee, he insisted, was to fight him in the open field near Washington. He concluded his second letter to Grant, however, by hinting that he would soon have a hand in drafting strategy for the eastern theatre, a closer hint that Grant was about to be appointed to the supreme command.

There had been strong rumours circulating to that effect, of which Grant cannot have been unaware. In February Congress passed an act reviving the rank of lieutenant general. The Confederacy appointed generals in the rank of brigadier, major general, lieutenant general, and by 1864 (full) general. In the Union army, however, major general was the highest rank granted and most Union generals held the rank in the United States volunteers, as Grant had done until his victory at Vicksburg. Then he was made a major general in the regular army. The new rank of lieutenant general was open to regular major generals, so Grant qualified for the promotion. The law allowed the lieutenant general to be appointed general in chief. In early March, Grant, still in Tennessee, received orders to go to Washington, where he arrived on March 8. He stayed first at Willard’s Hotel, where he received an invitation to attend a reception at the White House that evening. On his arrival there was a rise in the noise level. Grant knew almost no one in the capital, but since Vicksburg he was widely known there. The president recognised the signal and approached Grant with the words, “This is General Grant, is it?” After a few words, Grant was drawn away by the crowd, but later that evening Lincoln and Stanton took him into the Blue Room, where he was told that Lincoln would present him with his commission in the morning. The president also said that he would show him beforehand the draft of the short speech he would make. Lincoln may also have already known that Grant was tongue-tied and a hopelessly inept public speaker. He did, however, suggest that Grant should say something to forestall jealousy among other commanders and something to please the Army of the Potomac. It was entirely characteristic of Grant that when the time came he did neither. When nominated for the presidency, in 1868, his speech of acceptance ran to five words. On this occasion, when appointed by Lincoln in the White House room where the cabinet met, the president made a short but elaborate speech. “With this high honour devolves upon you also a corresponding responsibility. As the country herein trusts you, so, under God, it will sustain you. I scarcely need add that with what I here speak for the nation goes my own hearty personal concurrence.”2 Grant had an answer written on a half sheet of paper but read it so haltingly that his words were not recorded.

The day after his appointment the U.S. War Department announced the termination of Halleck’s position as general in chief but his reappointment in the new office of chief of staff. Thus was inaugurated in the United States what would become the normal arrangement of a modern command system, with Lincoln as supreme commander, Grant as operational commander, and Halleck as principal military administrator. Over the course of the next century the high command structure of all large armies would be adjusted to conform, beginning with the Prussian, where, in 1870-71, Bismarck acted as supreme commander and Moltke the elder as chief of operations. The rationalisation of the Federal or, as Grant called them, the national armed forces was essential, for under him, on his assumption of the generalship in chief, there were seventeen different Union commanders overseeing 533,000 men. The most important was the Army of the Potomac, which still lingered in northern Virginia opposite Lee’s army but was not at that time undertaking active operations. Elsewhere the military situation was determined by the Confederate deployments, which principally included that of Johnston’s Army of Tennessee at Dalton, Georgia, on the Western and Atlantic Railroad, which ran from Chattanooga to Atlanta. The other large Confederate force in the West was the cavalry corps under Nathan Bedford Forrest, located in eastern Tennessee. Forrest was a potential threat since he might raid as far as Cincinnati but as long as he was detached from either of the big Confederate armies, Lee’s and Johnston’s, he did not really multiply Confederate power.

Grant, as general in chief, could now consider what large operations he might launch. His first act in high command was to return to the West, to confer with Sherman, who, at his behest, had been appointed to succeed him. Grant had already identified Sherman as the most competent of his subordinates, a true battle-winning soldier of indefatigable temperament. He had also secured the advancement of Sheridan, another western general who had won his good opinion, to come east as commander of the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry, replacing Pleasanton, who was competent but lacked the aggressiveness by which Grant set such store.

On his visit to Sherman, Grant outlined his general philosophy for what he intended to be the closing stages of the war. It coincided with and may have been inspired by what was now Lincoln’s fixed conception of strategy, formed by trial and error in three years of frustration. Lincoln in 1861 had known nothing of war, but harsh experience had now taught him some essentials which he held with the force of unshakable conviction. He had abandoned altogether the conventional thought that the capture of the enemy’s capital would bring victory. Instead he now correctly perceived that it was only the destruction of the South’s main army that would defeat the Confederacy and he had enlarged that perception to believe that it would be achieved by attacking the enemy at several points simultaneously.

This is what the French have called a “rich solution” to the problem of the Civil War, open only to the side with greater numbers and several armies, as opposed to the South’s strategy of a “poor power” with weaker numbers and effectively only one or at most one and a half armies. Halleck, an extremely orthodox military thinker, had replied that the proper response to the rebellion was to concentrate the North’s force at decisive points: “To operate on exterior lines against an enemy occupying a central position will fail, as it has always failed, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred. It is undermined by every military authority I have ever read.” Lincoln had read almost no military textbooks while Grant had profited from the notoriously patchy West Point syllabus by avoiding most of them also. It was a merit of West Point that its teaching, though dusty to a degree, was practical—mathematics and engineering—which were actually useful, particularly during his efforts to alter the geography of the Mississippi Valley in 1863. A doctrine that Grant might have imbibed but did not was that of the climactic battle, which at a single strike resolved a conflict and ended it. The doctrine has been called Napoleonic, and with reason. Napoleon was the master of the great battle and his name was associated with several which had ended conflicts and altered history. Lee aspired to fight such battles and to end the war with the Union by a single overpowering act, as Napoleon had ended the conflict with Prussia in 1806 by winning the battles of Jena-Auerstedt and had almost ended the war with Russia by fighting at Borodino in 1812. Ultimately Napoleon, however, had been the victim of his own method, Waterloo having been the outstandingly decisive battle of the Napoleonic Wars. Since 1815, moreover, there had been few, if any, decisive battles. Indeed the era of decisive battles was drawing to a close. There would be several during Prussia’s wars of unification in 1866-71, notably the victory of Königgrätz-Sadowa against Austria, and Sedan against France in 1870. At the end of the era, states were learning to deny an enemy the chance of decisive battle by enlarging the size of their armies to a point at which it became difficult, if not impossible, to dispose of them in a single passage of fighting, while at the same time resorting to unorthodox tactics which would involve an opponent in guerrilla warfare or the tactics of protracted warfare should the main field army suffer defeat. France would cheat Prussia of a clear-cut decision in 1870-71 by resorting to a war in the provinces with irregular forces after the defeat of Sedan.

In mid-1863, the Union was approaching the point where it would have to decide by what military means the war was to be concluded: by pursuing the object of the final decisive battle or by some less direct method. Likewise, the Confederacy, which was rapidly losing the power to fight and win large-scale battles, would have to consider whether it should turn to protracted guerrilla tactics if it was to stave off defeat. The instructions Grant gave to Sherman on his visit to the western armies following his appointment as general in chief would soon confront the Confederacy with the necessity of fighting a small-scale, low-level war within its own territory, as opposed to a conventional army-to-army war on its frontier. Grant’s written instructions to Sherman were “to move against Johnston’s army, to break it up and to get into the interior of the enemy’s country as far as you can, inflicting all the damage you can against their war resources.” Sherman was perfectly willing to carry out such instructions since he had already formed the conclusion that the quickest way to break the Confederacy was to make its ordinary people suffer.

To Meade, commanding the Army of the Potomac, Grant sent the order, “Lee’s army will be your objective point. Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also.” Grant had already decided, with Lincoln’s approval, to make his headquarters with Meade, while leaving him as much freedom of action as possible. That would require nice judgement, not always achieved. Meade would complain frequently in his letters to his wife that any achievement of the Army of the Potomac was credited by the press to Grant, any failure to himself. Still, Grant’s intentions were fair and honest, and the two men would sustain an equable working relationship throughout the rest of the campaign in the East.

Meanwhile, in the West, Sherman was beginning what would become the culminating campaign of the war.