True Heroes of Balaklava

A4, 20pp., illustrated, published by the Crimean War Research Society, 1996.

A review of the role of the Turkish forces at the Battle of Balaklava. Treated as cowards at the time, and blamed for many of the reverses of the battle, this work re-evaluates the contribution of the Turkish troops and concludes that their stubborn defence of the redoubts along the Causeway Heights, no less than their often-ignored contribution to the Thin Red Line, makes the Turks the true heroes of Balaklava.

“a reasoned attempt to revise and sharpen our perceptions of the Turks and their conduct at the battle [of Balaklava]… well-illustrated with diagrams and maps… a valuable reassessment.” – Andrew Sewell in the War Correspondent.

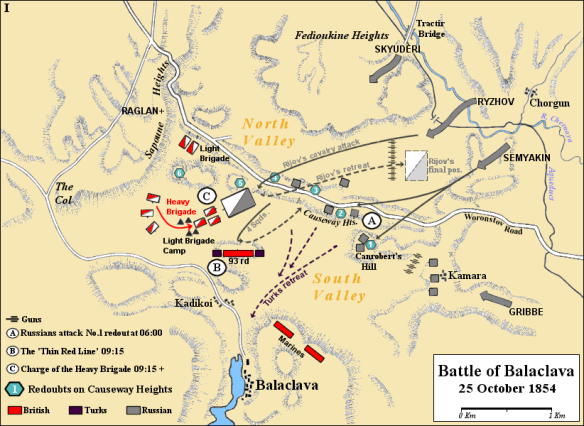

Battle of Balaclava. Ryzhov‘s cavalry attacks over the Causeway Heights at approximately 09:15. Both branches of the attack happened almost simultaneously.

The Ottoman guns from No.1 redoubt on Canrobert’s hill fired on the Russians at around 06:00 – the Battle of Balaclava had begun. Lucan despatched Captain Charteris to inform Raglan that the redoubts were under attack. Charteris arrived at around 07:00, but those at the British headquarters had already heard the sound of the guns. Lucan himself rode quickly back towards Kadikoi to confer with Colin Campbell, commander of the Balaclava defences. The two men agreed that this was not another Russian feint, but an attack in force with the intention of taking the British base. Campbell prepared his 93rd Highlanders to meet the enemy, whilst Lucan returned to the cavalry. Leaving the Light Brigade where it stood, Lucan led the Heavy Brigade towards the redoubts, hoping his presence might discourage any further Russian advance on Balaclava. Realizing his show of strength had little impact, however, Lucan led the Heavies back to their original position alongside the Light Brigade. The Ottoman forces were left to face the full force of the Russian assault almost alone.

Whilst Gribbe’s artillery continued to shell No.1 redoubt, the Russian columns under Levutsky, Semyakin, and Skyuderi began to move into the North Valley. Although the Heavy Brigade had pulled back, the British did send forward their available artillery to assist the Ottoman forces on the Causeway Heights. Captain George Maude’s troop of horse artillery, I Troop, unlimbered its four 6-pounder and two 12-pounder guns between redoubts 2 and 3, whilst Captain Barker’s battery, W Battery, of the Royal Artillery, moved out of Balaclava and took its position on Maude’s left. However, the artillery duel was a very one sided affair. The heavier Russian guns (some 18-pounders), particularly No.4 battery under Lieutenant Postikov, together with the riflemen of the Ukraine regiment, took their toll on both men and ordinance. Running short of ammunition and taking hits, Maude’s troop was forced to retire, their place taken by two guns from Barker’s battery (Maude himself was severely wounded). As the British artillery fire slackened, Semyakin prepared to storm No. 1 redoubt, personally leading the assault together with three battalions of the Azovsky Regiment under Colonel Krudener. “I waved my hat on both sides.” Recalled Semyakin, “Everybody rushed after me and I was protected by the stern Azovs.” The Ottoman forces on Canrobert’s Hill resisted stubbornly. Although the attack had begun at 06:00, it was not until 07:30 when No.1 redoubt fell. During that time the 600 Ottoman defenders had suffered from the heavy artillery bombardment; in the ensuing fight in the redoubt and subsequent pursuit by the Cossacks, an estimated 170 Ottomans were killed. In his first report of the action for The Times, William Russell wrote that the Turks ‘received a few shots and then bolted’, but afterwards admitted that he had not been a witness to the start of the battle, confessing, ‘Our treatment of the Turks was unfair … ignorant as we were that the Turkish in No.1 redoubt lost more than a fourth of their number ere they abandoned it to the enemy’. Later Lucan and Campbell too acknowledged the firmness with which the assault on No 1 redoubt, which was not visible from their vantage point, had been resisted; it was not until this had been overwhelmed did the defenders abandon redoubts 2, 3 and 4. Of the estimated 2,500 Russians who took part in the assault the Azovsky Regiment lost two officers and 149 men killed.

The remaining redoubts were now in danger of falling into the hands of the oncoming Russians. The battalions of the Ukraine Regiment under Colonel Dudnitsky-Lishin, attacked redoubts Nos.2 and 3, whilst the Odessa Regiment under Skyuderi, advanced on redoubt No.4. The Ottoman forces in these positions, having already watched their compatriots flee the first redoubt and realizing that the British were not coming to their aid, retreated back towards Balaclava, pursued by the Cossacks who had little trouble dispatching any stray or isolated men; the few British NCOs could do nothing but spike the guns, rendering them unusable. The Ottoman forces had gained some time for the Allies. Nevertheless, by 08:00 the Russians were occupying redoubts 1, 2 and 3, and, considering it too close to the enemy, had razed redoubt No.4.

#

The role of the Ottoman division during the initial stage of the siege is not clear. Most probably it also took part in the costly French attack. Additionally, thanks to the miscalculation and neglect of allied quartermasters, it suffered further casualties because of poor diet and lack of provisions. But, its role in the Balaclava (Balýklýova) battle is well known, albeit not with glory. The Russian main army group attacked the relatively weakly defended allied security perimeter around Voronzov Ridge. At least four Ottoman battalions reinforced with artillery gunners, some 2,000 men (more or less) manned five poorly fortified redoubts that established the forward defensive line. What happened at these redoubts during the early morning of October 25 is still shrouded in mystery. According to the commonly accepted version, the Ottoman soldiers cowardly fled when the first Russian shells began to land, leaving their cannons behind. The day was saved thanks to the British Heavy Cavalry Brigade and the famous ‘‘thin red line’’ of the 93rd Highlander Regiment. The alleged cowardly behavior then became so established in the minds of the allied commanders that Lord Raglan refused to assign Ottoman troops to reinforce his weak defensive forces at Inkerman Ridge just before the battle of the same name.

Recent research, however, including battlefield archeology, provides a completely different story and corresponds to the version of events contained in the modern official Turkish military history. According to these recent findings, the Ottoman battalions in the redoubts, especially the ones in Redoubt One, defended their positions and stopped the massive Russian assault for more than two hours with only their rifles; the British 12 pounder iron cannons located there could not be used without help. Their efforts gained valuable time for the British to react effectively. The battalion in Redoubt One was literally annihilated and the others, after suffering heavy casualties, were forced to retreat. They did not flee, because we know that some of them regrouped with the 93rd Highland Regiment and manned the famous ‘‘thin red line.’’ It is evident that Ottoman soldiers were also heroes at Balaclava. However, because of factors including racial xenophobia, language barriers, and lack of representation at the war council in Crimea, their valor was tarnished, and they were chosen as scapegoats and blamed for many of the blunders that occurred during the battle.