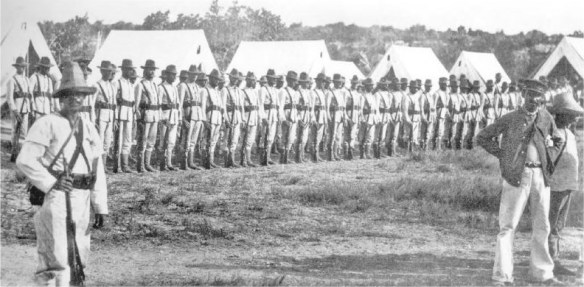

U.S. Marines form up in their camp in Cuba in 1898.

When Admiral Cervera’s Squadron had been trapped in the harbor of Santiago, the American fleet settled down to a grim and unwearied blockade, thereby beginning a new naval phase of the Spanish-American War, with new problems to be met and new plans to meet any exigency.

One problem confronting Admiral Sampson was the establishment of a base not too far away where his ships could be coaled and minor repairs effected. An ideal location for such a base was Guantanamo Bay, only about 60 miles to the eastward of Santiago.

On June 7, 1898, the small, unprotected cruiser Marblehead, Commander Bowman McCalla, U.S. Navy, reconnoitered the bay in company with the auxiliary cruisers Yankee and St. Louis, and drove the little Spanish gunboat Sandoval into the shoal waters of the inner harbor, quite out of range of the deep draft ships.

While the St. Louis was cutting the cable, a detachment of marines comprising the cruiser New York’s marine guard, 40 from the battleship Oregon and 20 from the Marblehead, landed from the cruiser under the command of Captain M. C. Goodrell, U.S. Marine Corps, of the New York. The landing party burned the few huts at Playa del Este, destroyed the cable station at the mouth of the bay, and hunted vainly for Spanish soldiers who had scattered under the preliminary shelling by the ships.

The marines re-embarked and the Yankee departed with the New York and Oregon contingents, leaving the Marblehead to watch the bay alone for the next three days. Then on June 10 the naval transport Panther arrived with the dispatch boat Dolphin in company.

The Panther had on board 23 officers of the Marine Corps, a naval surgeon, and 623 marine enlisted men, all under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Robert W. Huntington, U.S. Marine Corps, who had instructions to land and establish a base for the fleet.

Thus, while Admiral Sampson lay off Santiago holding Cervera a prisoner and awaiting the arrival of the Army, the first actual invasion of Cuba by United States forces began at Guantanamo Bay. The marines filled whaleboats and cutters and were towed to the beach by steam launches. They landed with precision, and in less than an hour the entire battalion was ashore with its tents and supplies.

Climbing a hill that rose sharply from the beach, the battalion reached the summit without opposition, finding itself on a plateau several acres in size and dotted with woods and chaparral. Soon, tents appeared in trim rows, while parties were sent out to clear the brush about the camp, a job that proved almost hopeless with the appliances at hand.

The battalion settled down for the night without seeing a single Spaniard. But darkness brought the enemy and guerrillas began popping at the outposts, killing two privates, James McColgan and William Dumphy, and preventing the weary marines from obtaining sleep. The Marblehead and Dolphin shelled the surrounding countryside but were unable to dislodge the Spaniards from cover. Assistant Surgeon John Blair Gibbs, U.S. Navy, was killed in front of his tent, and Sergeant C. H. Smith was shot dead in the front lines before daylight came. The night’s toll also included several men wounded.

The Spaniards continued to harass the marines, laboring to deepen their shallow rifle pits, and on the morning of the 12th Sergeant Major Henry Good was killed. That day a force of 60 Cubans, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas, joined the marines. Colonel Huntington said of these: “They, being acquainted with the country and excellent woodsmen and fearless, were of the greatest assistance.”

The marines were under steady rifle fire from the brush and the morning of the 14th brought the sixth death to the command, when Private Goode Taurman fell off a cliff and was killed. The wounded had reached a total of 22.

With his men worn out from lack of sleep and growing steadily more irritable under the annoyance of the guerrilla peppering, Colonel Huntington assumed the offensive on the 14th. He sent Companies C and D, with the 60 Cubans, to destroy a well about 6 miles from camp. This well was said to be the only Spanish water supply within 9 miles, and without it the Spaniards would be compelled to retire to Caimanera, a small garrison town about 10 miles from the bay proper and thus out of reach of the ships.

Another force of Spaniards, more numerous than the marines, was located around Playa del Este, on the eastern arm of the harbor. This force remained discreetly inactive after discovering that Commander McCalla’s ships were quite ready to shell the shore, given the slightest excuse.

The well-taking expedition, 211 men in all, with Captain G. F. Elliott, senior officer of the marines, left camp under the command of the Cuban Lieutenant Colonel Thomas and was soon mixed up in a hot little scrap with some 500 Spaniards that lasted from about 11:00 A.M. until nearly 3:00 P.M.

They fought over the ridges and through brush-choked valleys until the Spaniards finally fled in disorder, leaving 60 dead including two officers. A lieutenant and 17 privates were captured by the Americans. Three marines were wounded, while the Cubans had two killed and two wounded.

Captain Elliott’s report particularly commended First Lieutenant W. C. Neville, who injured a hip and an ankle in a fall after the fight was over; First Lieutenant L. C. Lucas, commanding Company C; Captain William F. Spicer, commanding Company D; Second Lieutenants L. J. Magill, P. M. Bannon and M. J. Shaw; Sergeant John H. Quick, who constantly exposed himself to enemy fire while signaling to the Dolphin, and Privates Faulkner, Boniface, and Carter for unusually deadly marksmanship.

The report cites the effectiveness of shellfire from the Dolphin, Commander H. W. Lyon, and the care that ship gave 12 marines, including Captain Spicer, who were overcome by the heat and sent out to her for treatment.

This fight, in which Captain Elliott also distinguished himself, brought an end to Spanish action against the marine battalion, and no further sniping occurred, although vigilance was maintained to guard against a surprise attack.

Relieved of enemy pressure, the marines strengthened their position while bluejackets landed stores, rebuilt the cable house, and spliced the cut cable, giving the Navy its own communication channel.

With this work in hand, Admiral Sampson sent the battleship Texas and the Suwanee, an armed lighthouse tender, to shell a small fort on the western arm of the harbor, the opposite side to the location of the marine camp. Occasional firing had come from this fort, and it was necessary to drive all the enemy from the area and back to Caimanera if the bay was to be entirely safe for the coaling and repair of ships.

The fort could provide little resistance, but an element of danger entered into the attack through the presence of submarine mines in the western channel. The fort was destroyed by the two ships with the assistance of the Marblehead which picked up a contact mine on her propeller. The Texas also knocked one adrift, but, by good fortune, neither exploded.

With the last enemy work reduced, Sampson’s ships began regular coaling at Guantanamo, and they lay there untroubled to effect repairs when necessary. The water was deep enough for battleships, the climate was reasonably healthy, and no Spaniards appeared to mar the calm. The latter remained at Caimanera, and the little gunboat Sandoval also went up to that town, well out of range.

Steam launches kept the channel swept in case the Spaniards set mines adrift, and maintained a constant patrol against a possible torpedo attack by the Sandoval. But no attack ever came and the launch crews had only occasional opportunities to fire their little one-pounders at the distant gunboat, as their one relief from the monotony of their vigil.

On the 18th, Admiral Sampson, in his flagship New York, made his first visit to his squadron’s new base and found everything in excellent order. The marines were comfortable and healthy on shore—in fact not one death occurred through sickness during the entire marine occupation of Playa del Este. In the bay, the battleship Iowa and auxiliary cruiser Yankee lay peacefully coaling, while riding at anchor were the Marblehead, Dolphin, Panther, the hospital ship Solace, the lighthouse tender Armeria, and three colliers.

Probably nothing in the entire naval campaign against the Spanish forces in Cuba brought more credit to the acumen of Admiral Sampson than the acquisition of Guantanamo Bay, nor can the work done by the small force of marines in a strange country, confronted by enemies fully three times as numerous and well hidden by luxuriant undergrowth, be too highly praised. It was a model campaign and one described by no less an authority than the military expert of the London Standard, as a “master stroke.”