After four campaigns of ceaseless activity and intense stress, during which he had had to witness tens of thousands of dead and dying, all victims of his ambition, Frederick was beginning to feel the strain. Rarely healthy at the best of times, he was now increasingly prone to disabling bouts of illness, with gout and hemorrhoids to the fore. So fierce had been the attack of gout and attendant fever the previous autumn that his journey to Silesia at a crucial time had to be delayed. He had told Prince Henry: “I shall fly to you on the wings of patriotism and duty, but when I arrive you will find only a skeleton,” although he added that his feeble body would still be activated by his indomitable spirit. By January 1760 the spirit had wilted too. He wrote to d’Argens to thank him for the trouble he was taking to publish his “twaddle,” but asked how he could be expected to write good verse when his mind was “too disturbed, too agitated, too depressed.” There was no prospect of securing peace, he cried, and one more defeat would deliver the coup de grâce. Weighed down by care, surrounded by implacable enemies, life had become an insupportable burden…and so he went on in the same vein lamenting his fate.

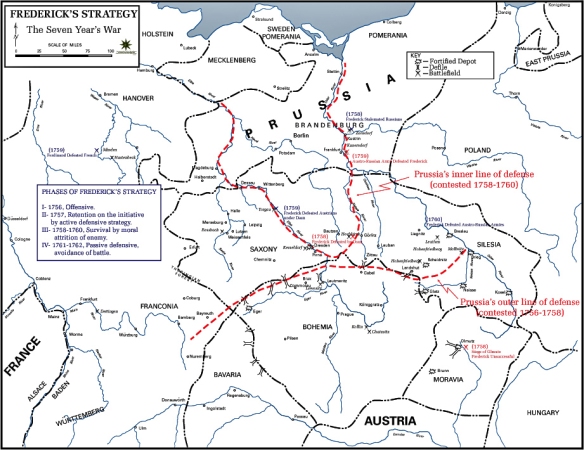

It was not quite yet a case of “darkest before dawn,” because Frederick had one even more tenebrous moment to survive. His overall strategy remained the same—to keep control of Saxony and Silesia—and so did his prime objective—the recapture of Dresden. How many troops he had at his disposal is a matter of dispute. The best guess is that he never had more than 110,000 on active duty, so his numerical inferiority was of the order of at least two to one. That disparity increased on 23 June when General de la Motte-Fouqué was overwhelmed at Landeshut by a greatly superior Austrian force under Laudon, losing 2,000 on the field of battle and another 8,000 in prisoners of war. Fewer than 1,500 managed to escape. Once again, a Prussian general had obeyed his royal master well but not wisely. Frederick had had second thoughts about his original order to hold Landeshut come what may, but his change of heart came too late to save Fouqué’s corps.

Back in Saxony, Frederick had been very active but without achieving anything. All his attempts to bring either Lacy or Daun to battle failed. So did his siege of Dresden, which began on 19 July only to be abandoned four days later. Three days after that, the Austrians showed him how a siege should be conducted when Laudon’s army took the great Silesian fortress of Glatz by storm. Admittedly, Dresden had been garrisoned by 14,000 veterans commanded by the determined Major General Macguire (sic), whereas the luckless Glatz commandant, Lieutenant Colonel Bartolomei d’O (also sic), had only 3,000 ill-motivated Saxons and Austrian deserters at his disposal. That did not save him from court-martial and execution when he eventually returned from Austrian captivity. The difference between the two defenses showed that the greater demographic resources of the Austrians were beginning to make themselves felt.

Frederick’s situation was now perilous in the extreme. He was losing control of both Saxony and Silesia and was running out of men, thanks to his own numerous mistakes. To make matters worse, a Russian corps under General Chernyshev had crossed the Oder and was advancing through Silesia to join up with Daun. Nothing, it seemed, lay between the allies and total victory but a few weakly defended Silesian fortresses. As soon as he had taken Glatz, Laudon moved off to Breslau, the greatest prize of all, confident that he could repeat his triumph. Now at last chinks of light began to shine through the gloom for Frederick: his commander at Breslau, General Bogislav Friedrich von Tauentzien, proved to be made of sterner stuff than his colleague d’O at Glatz; in a lightning march which took his army corps of around 35,000 over a hundred kilometers in three days, Prince Henry marched to Breslau’s relief; and the Russians failed to link up with Laudon. Meanwhile, Frederick had embarked on an epic march from Saxony to Silesia, which took up the first week of August, not so much pursued as accompanied by the main Austrian army commanded by Daun and a subsidiary corps under Lacy. So close were the three armies that they appeared to be one force. Urged on by Maria Theresa and Kaunitz, who demanded a battle to finish Frederick off, it was Daun’s intention to force an engagement on the Katzbach, a tributary of the Oder, north of Breslau.

That was what Daun got, on 15 August, but not in the manner he had expected. As his combined forces of 90,000 enjoyed a three-to-one superiority, he was confident he could encircle and eliminate Frederick’s army, which was camped a couple of kilometers northeast of Liegnitz. On this occasion, Frederick was not caught napping. On the contrary, during the night of 14–15 August he moved his army to the north, leaving his campfires burning to confuse the enemy. So when it began to get light shortly after 3 A.M., it was General Laudon who was taken by surprise. Expecting to be supported by Lacy and Daun, who were supposed to be advancing from the west and south, respectively, and unaware that he was facing the main Prussian army, Laudon attacked. Decimated by artillery, then taken in the flank, the Austrians were forced back to the Katzbach. By 6 A.M. the battle was all over. It had been short but sharp. It cost Laudon around 10,000, including 4,000 prisoners of war, among them two generals and eighty officers, and eighty-three pieces of artillery. The Prussians lost 775 dead and 2,500 wounded, most of them to two late cavalry charges which covered the Austrian withdrawal.

As the battles of the Seven Years’ War went, Liegnitz was not a particularly grand affair. Most of the Austrians never fired a shot in anger. Yet its importance was colossal. This was a battle Frederick had to win, or rather it was a battle he could not afford to lose. If Daun and Lacy’s hammer had smashed down on Laudon’s anvil, as had been intended, the Prussians in between would have been pulverized, to an even greater extent than at Kunersdorf. Any remnants would have been mopped up by a Russian force under Chernyshev which Saltykov had promised to send across the Oder on the 15th. In the event, the Russians now prudently went east rather than west, while Daun and the Austrians moved off to besiege the fortress of Schweidnitz to the west of Breslau. With the advantage of hindsight, we can see that Liegnitz was a pivotal moment in the Seven Years’ War. It brought to an end a sequence of military defeats stretching back to Hochkirch nearly two years previously (although some of Frederick’s subordinate generals, notably Prince Henry, had won minor engagements in the interim). Napoleon was not the first to realize the importance for an army’s morale of the belief that luck (also known variously as Providence, Fortune and God) was on its commander’s side. As Jomini observed, Liegnitz restored “toute sa force morale.” It also restored his reputation among the powers. The British secretary of state, Lord Holderness, wrote: “The superior genius of that great prince never appeared in a higher light than during this last expedition into Silesia. The whole maneuver is looked upon here as the masterpiece of military skill.” This was the best chance the Austro-Russians had had since Kunersdorf of bringing the war to an abrupt end and they knew it. Thereafter their offensive never regained momentum.

In the short term, this brief but violent flurry of activity was followed by several weeks of stalemate, as Daun and Frederick maneuverd around each other in the hills of western Silesia. At the end of September, Frederick complained to Prince Henry that he was getting nowhere. Daun was in one camp, Frederick in another, and both were invulnerable. The impasse was broken further north by an unusually vigorous if brief initiative on the part of the Russians, spurred on by the French military attaché in their camp. In the first week of October, a force led by Chernyshev occupied Berlin, where they were joined by 18,000 Austrians and Saxons detached from Daun’s army. Although this was an expensive and disagreeable experience for the inhabitants, and a good deal of vandalism was perpetrated at the palaces of Charlottenburg and Schönhausen, the three-day occupation had no military consequences. The main casualties were the fifteen Russian soldiers killed during an incompetent attempt to blow up the powder mill. As Showalter has commented, “It was a raid as opposed to an operational maneuver.”

Liegnitz did nothing to repair Frederick’s personal morale. He lamented to Prince Henry that his resources were too narrow and shallow to resist the overwhelming numerical superiority of his various enemies, adding, “And if we perish, you can date our eclipse to that pernicious affair at Maxen.” He now had to realize that the ever-cautious Daun had got the better of him in Silesia and that he must march back to Saxony if the campaign was not to end in total failure. It was in a grim mood that he set out, telling Prince Henry on 7 October that “given my present situation, my only motto can be: conquer or die.” Daun was also under pressure from Vienna, from which an increasingly impatient Maria Theresa sent an express order to maintain control of Saxony against Frederick and to seek the necessary battle no matter what the circumstances. In the event, Frederick took the battle to him, on 3 November at Torgau to the northeast of Leipzig, where the Austrians had taken up a strong defensive position. If they could not be dislodged, Saxony and its resources would be lost. To attack head-on invited a disaster along the lines of Kunersdorf, so Frederick embarked on an imaginative outflanking movement designed to take the bulk of his army—24,000 infantry, 6,500 cavalry and fifty twelve-pound guns—to attack the Austrians in the rear. Their attention would be diverted to their front by a smaller force of 11,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry commanded by General von Zieten. The drawback turned out to be the long march needed to get the main army into position. Too much could and did go wrong, so that it all took too long and allowed Daun to take effective counteraction.

The battle that ensued was even more ferocious than previous encounters between the two sides. Frederick himself was stunned when hit by a spent bullet and had to be carried from the field for a time. What turned out to be the bloodiest victory of his career was won by a combination of individual initiatives by junior officers at crucial moments and the timely advance of Zieten’s corps. Until almost literally one minute to midnight, the result was in the balance. Indeed, Daun had already sent off a courier announcing a victory when the tide turned, a mistake which caused intense despondency in Vienna when the initial rejoicing turned to ashes. The losses on both sides were horrific. In a letter to Prince Henry written the following day, Frederick claimed that in this “rough and stubborn” battle he had inflicted 20,000 to 25,000 casualties. He did not even mention his own. When his adjutant, Georg Heinrich von Berenhorst, produced the final score some days after the battle, Frederick told him: “It will cost you your head, if this figure ever gets out!” It cannot be known just how high it really was, the estimates ranging from 16,670 to 24,700, but even the lowest exceeded the Austrian total (which Frederick greatly exaggerated).

Although he talked up his victory, Frederick was not in a victorious mood. The losses had been so heavy that in the future such offensive tactics simply could not be afforded. As he wrote to d’Argens on 5 November, he had secured a period of peace for the winter but that was all. Five days later he added that the Austrians had been sent back to Dresden but from there they could not be dislodged for the time being. He went on:

In truth, this is a wretched prospect and a poor reward for all the exhaustion and colossal effort which this campaign has cost us. My only support in the midst of all these aggravations is my philosophy; this is the staff on which I lean and my only source of consolation at this time of trouble when everything is falling apart. As you will see, my dear marquis, I am not inflating my success. I am just telling it like it is; perhaps the rest of the world will be dazzled by the glamour a victory bestows, but “From afar we are envied, on the spot we tremble.”

This was just the sort of gloomy mood in which he had begun the year. He was perhaps being too hard on himself; 1760 had been a decidedly better year than 1759. The Austrians and Russians had failed to combine effectively, he had won two major engagements and the only net loss was the fortress of Glatz. A more judicious assessment would be given by Clausewitz. While disagreeing with those who saw the campaign as a work of art and a masterpiece, he did find admirable

the King’s wisdom: pursuing a major objective with limited resources, he did not try to undertake anything beyond his strength, but always just enough to get him what he wanted…His whole conduct…shows an element of restrained strength, which was always in balance, never lacking in vigor, rising to remarkable heights in moments of crisis, but immediately afterwards reverting to a state of calm oscillation, always ready to adjust to the smallest shift in the political situation. Neither vanity, nor ambition, nor vindictiveness could move him from this course, and it was this course alone that brought him success.

Much less satisfactory was the situation on the western front. French losses overseas in 1759 forced them to seek victory in Germany as a bargaining counter for the eventual peace negotiations. A large army of around 150,000 was unleashed in June 1760. Prince Ferdinand was forced back from Hessen and much of Westphalia, despite winning a number of engagements. Victory at Warburg on 31 July could not stop the French taking Göttingen a week later, although that proved to be the limit of their advance into Hanoverian territory. More ominous in the long term for Frederick was the diminishing enthusiasm on the part of his British allies for the continental war. They had achieved virtually all their war aims in North America, the Caribbean and India and were now looking for an early end to what had become a ruinously expensive war. Moreover, the death of George II on 25 October brought to the throne a king who the previous year had referred to Hanover as “that horrid Electorate which has always liv’d upon the very vitals of this poor Country.” It could be only a matter of time before the invaluable British subsidies to Frederick were halted. In December the Prussian representative in London, Knyphausen, warned Frederick of the growing opposition in Parliament to the continental war and corresponding enthusiasm for a separate peace with France.