Londinium was equipped with massive defenses: several forts were built along with the immense London Wall, remains of which are still recognizable in the city.

Londinium Bridge. This model shows how the Romans built the first bridge across the River Thames, where London Bridge now stands.

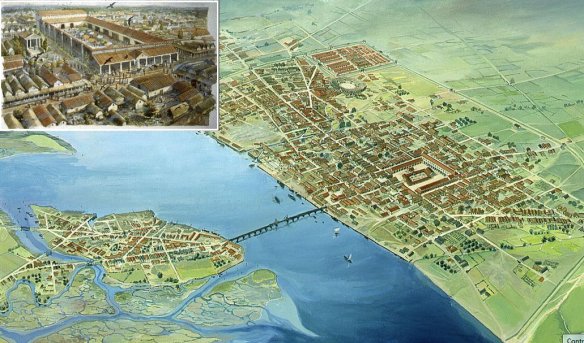

It was the geographical features of the area that brought about the foundation of Roman London. There is no strong evidence of any occupation on the site before the conquest in AD 43. London stands at the lowest convenient bridging point of the THAMES. There was a way through the marshes from the south and on the north side two gravel hills (now ST PAUL’S and CORNHILL) stood above the flood plain and gave a firm foothold. The combination of these elements of topography and geology gave the site a military importance in the eyes of Roman army surveyors. There can be no doubt that military necessity provided the impetus for the bridging of the Thames and the establishment of a settlement on the north bank. Both the Roman government and private traders then took advantage of the convenience of the site.

The Thames was much wider and shallower than it is now. Recent excavation evidence, however, plus alignments of roads coming from the south through SOUTHWARK, suggests that the original alignment of the ROMAN ROAD Watling Street centred on the WESTMINSTER area and a possible ford. In about AD 50 new roads in Southwark were built converging on a point across the river from the site of the new settlement. Pottery and coin evidence indicates that the city was not begun until this date. The fledgling city was destroyed soon after in AD 60 during the revolt of Queen Boudicca and her tribe, the Iceni. Tacitus in his accounts notes that at this time London was not yet classified as a full Roman settlement but was an important centre for businessmen. The Governor of Britain, Suetonius Paulinus, raced to reach London but his assembled forces were not large enough to save the town and he evacuated those inhabitants able to leave. Boudicca destroyed the town by fire and massacred those left behind. Colchester and St Albans suffered the same fate. Evidence of the disaster can be found in the layers of burnt debris and pottery.

The archaeological evidence of recent years shows that there was a basic plan from the beginning for the growth of Londinium, ultimately to extend over the 330 acres it was to occupy when walled in the late 2nd century. Fine wares, glass, jewellery and other objects from the Mediterranean testify to the city’s importance as a commercial entrepôt. In the rebuilding after the disaster priority seems to have been given to business premises, no doubt fostered by the benevolent eye of the newly appointed procurator (tax collector), Julius Classicianus. He realized that repression after the revolt would not regain lost taxes and is recorded as having set the province on its feet again. The fragments of his grand tomb, erected by his sorrowing wife Julia Pacata, were found on TOWER HILL in 1852 and 1935 and are now restored in the BRITISH MUSEUM. (A copy of the inscription is in the MUSEUM OF LONDON and on site at Tower Hill.)

The nucleus of the new settlement was on Cornhill and around the walbrook stream, the town’s main source of water. By the AD 70s the settlement had expanded and the main public buildings, the basilica and FORUM, were in place on high ground to the east of the Walbrook. By the end of the 1st century other public buildings, the GOVERNOR’S PALACE, the Amphitheatre and the ROMAN BATHS in Cheapside and Upper Thames Street, had been added.

The commercial vitality and growth of Londinium depended on the port facilities. The waterfront lay about 100 metres north of its present position, just north of UPPER and LOWER THAMES STREET. Excavations near PUDDING LANE revealed a mid-1st-century wooden landing stage which was superseded by a major timber-faced quay some twenty years later. The quay was backed by warehouses which continued in use until the end of the 4th century. New waterfronts were built in the 2nd century and again in the early 3rd century, as shown in excavations at CUSTOM HOUSE, ST MAGNUS and Seal House. This last waterfront extended for at least 550 metres.

Londinium reached its zenith in the early 2nd century. It saw the visit of the Emperor Hadrian in AD 122 and the building of the fort and rebuilding of most public buildings prior to that date indicate some preparation for an imperial visit. Fire again destroyed an area of the city in AD 125–130. Excavations west of the Walbrook provided evidence of the area’s recovery after the fire. It was extensively replanned and rebuilt as shops and houses. However, by the end of the 2nd century the area was abandoned with little trace of later-Roman occupation.

The economic effects of Clodius Albinus’s revolt in AD 192 must have been felt, but were soon overcome when Septimius Severus defeated Albinus and came to Britain himself, to die at York in AD 211. It was about this time that the province was divided into two, with York as the capital of Britannia Inferior, and London the capital of Britannia Superior. It left London less a military and commercial area in the 3rd century and more an administrative city. The encircling city wall was also built around AD 200, evidence for the transportation of its construction materials being found in the Blackfriars barge.

Public monuments of some size were erected in the early 3rd century, including a monumental arch (pieces of which have recently been found as part of the later 4th-century river wall). The TEMPLE OF MITHRAS was built about AD 240 on the east bank of the Walbrook and continued in use until early in the 4th century. An altar inscription, found reused in the river wall, indicates a TEMPLE OF ISIS was rebuilt some time between AD 251 and 259. During the 3rd century, however, the city’s population appears to have changed from that of all classes and occupations to a much smaller population drawn from the wealthier levels of society. A number of large polychrome mosaics from private houses testify to the wealth of certain members of the population, doubtless rich merchants or government officials. With the contraction of the population, many buildings were demolished and not rebuilt and the industrial workshops around the Walbrook were replaced by private houses.

At the end of the 3rd century came the revolt of Carausius (AD 287–93), followed by that of Allectus (AD 293–6). Constantius Chlorus rescued London from being ransacked by Allectus’ army in AD. A mint was established in London by the usurper Carausius in AD 288 and continued in use, after his defeat, until AD 326. It opened again for a short time in AD 383, using London’s 4th-century name Augusta.

At the start of the 4th century, Britain was divided into four smaller provinces and Londinium became the capital of Maxima Caesariensis. This was in accordance with the Emperor Diocletian’s policy of devolution to improve administrative efficiency. The city’s defences were strengthened in the same century. A huge section of wall still in a remarkable state of preservation was found within the TOWER OF LONDON in 1977. This can almost certainly be ascribed to the known restoration work carried out in 396 at the orders of Stilicho, a great general under the Emperor Honorius. Stilicho had kept the Visigoths at bay in Italy, and when he was executed as the result of a palace intrigue in 408 it left a weak emperor helpless at Ravenna. The way was open for the barbarians to attack, which itself led to the recall of the legions from Britain by Honorius in 410. Some 50 years later the walls of London were still high and strong enough to afford protection against the Saxons, but it is not known for how long after the mid-5th century the city remained inhabited.

It was probably not for long. There is little archaeological evidence but the Anglo-Saxons, it is known, especially from several poems, stood in awe and dread and shunned ‘the work of giants’ as they called the Roman buildings, now standing derelict.

London, according to the twelfth-century chronicler Geoffrey of Monmouth, was founded in 1108 BC by Brute, a god or demi-god descended from Venus and Jupiter. About a thousand years later King Lud, said to be a close relative of Cassivelaunus, the British chieftain contemporary with Julius Caesar, improved the place and named it Ludstown in honour of himself. John Stow, the Elizabethan historian, derided this explanation of the name, though he failed to offer any convincing alternatives. In more recent times the name was said to be derived from a personal name based on londo, fierce or bold, or from a tribal name. This is now discredited by most modern scholars. All that is certain is that the Romans frequently made use of Latin names and anglicized them and that within a few years of the conquest in AD 43 the place was known as Londinium. There is a late-1st-century ad jug in the Museum of London whose inscription includes the word Londini.

ROMAN FORT • London Wall, EC1.

Still preserves the line of the Via Praetoria (main street). The Via Principalis of the fort ran at right angles to it. The fort was built to the north-west of the city in the early 2nd century according to the coin and pottery evidence. Since it would have had little defensive effect it probably served as a barracks for the garrison attached to the Governor’s Palace. Substantial portions of the barracks are buried under WOOD STREET police station. The area of the fort was about 12 acres with the usual playing-card shape associated with such forts – about 270 metres north to south by 220 metres east to west. Although the stone walls were quite substantial they were not felt to be strong enough when the fort was incorporated into the LONDON WALL at the end of the 2nd century. The north and west sides were thickened on their inside face by additional layers of masonry with rubble infill that brought these walls up to the required width. The two parts side by side can be seen in the remains in the public garden in NOBLE STREET. In a room at the west end of the underground car park (entrance from London Wall) are the remains of the west gate of the fort and part of a guardroom excavated in 1956.

ROMAN ROADS

London was the hub of the Roman road network in Britain, but to understand how the system developed it is necesary to go back a little farther, to pre-Roman times. The River THAMES was the most important factor. Before the embankments were built in the 19th century, it was wide and shallow. In the Roman period, the land level was higher than at present, and the tide would not have risen much above WESTMINSTER, which became a convenient fording place for traders wishing to cross the river. Travelling inland from the Kentish ports, travellers would have crossed the Westminster ford, and then struck north or west to the important tribal capitals at Wheathampstead (near St Albans) or Silchester, west of Reading. An east–west route would also have developed, aiming for the third of the main tribal centres, at Colchester, following a track which kept to high ground along the line of OXFORD STREET and OLD STREET. It is likely that Roman engineers made use of these routes; the two main alignments of WATLING STREET north and south of the river converge on the early river crossing. When LONDON BRIDGE was built (within 15 years of the Roman invasion of AD 43), short connecting tracks would have been made to the nearest established roads.

The long straight alignments of Roman roads resulted from the method of surveying used by the engineers who built them. The roads were set out by sighting between points on high ground, the actual lines being carefully chosen to avoid, if possible, steep inclines and marshy ground. Roads would deviate from the direct line if there were advantages such as better ground conditions; a good example is the diversion of Stane Street at Ewell, which follows the chalk formation and stays clear of the difficult London clay for several miles. Important Roman roads were usually about 7 metres wide, and were frequently set on an embankment about 1.5 metres high, known as an agger. Excavations of buried roads reveal the original surface layer of fine stone chippings.

For much of their length, the Roman roads in London are still in use as modern thoroughfares.

Watling Street • This approaches from Dover, Canterbury and Richborough along the line of SHOOTERS HILL, before taking a curving route through DEPTFORD and NEW CROSS much like the present road. Northward, the alignment is followed almost exactly by the present road from MARBLE ARCH to EDGWARE. The substantial construction of the original road has been disclosed by excavations for pipe-laying.

Ermine Street • This was the main artery to Lincoln and York, and its course from BISHOPSGATE is closely represented by Kingsland Road, Stoke Newington Road and Stamford Hill.

Colchester Road • It is followed by present roads east of STRATFORD. The River LEA was crossed at OLD FORD, where remains of Roman masonry have been found near Iceland Wharf. From this point, a road must have gone direct to ALDGATE and on, if not to the bridge, at least to the main east–west street through LONDINIUM. Evidence is scant for such a road.

Silchester Road • This was the main artery to the west of England. It is represented by the course of OXFORD STREET, NOTTING HILL (a possible surveying point), HOLLAND PARK and GOLDHAWK ROAD, where remains have been excavated. Eastward, the road must have connected to NEWGATE, with a branch to OLD STREET, OLD FORD and STRATFORD; much of this route is now lost.

Ludgate–Hammersmith • A Romanized form of the early trackway followed the line of the STRAND through KENSINGTON, to join the main western road at CHISWICK.

Stane Street • It connected London with Chichester, the tribal capital of Sussex, and its course is approximately that of the present road from BOROUGH HIGH STREET to TOOTING. Traces have been found under buildings in Borough High Street, and the buried road surface directly under NEWINGTON Causeway. With the passage of time, the modern road has deviated in places; BALHAM HIGH STREET is about 55 metres from the original line, and CLAPHAM COMMON South Side almost a quarter of a mile further west, but Clapham Road and Kennington Park Road are on the Roman line.

London–Brighton • This was an important road for the traffic in corn and iron from Sussex. It probably branched from Stane Street at Kennington Park, on the course of Brixton Road, Brixton Hill and Streatham Hill.

London–Lewes • This road also served the corn-growing and iron-producing areas of Sussex. Its course in London has been traced by careful probing and digging in gardens and allotments. Branching from WATLING STREET at Asylum Road, PECKHAM, it followed the alignment of Blyth Hill, CATFORD, where the buried agger remains intact. It then ran through west WICKHAM to a point on the North Downs. The only section of this road in use today is the three mile straight length through Edenbridge, but the route has survived in the form of parish boundaries and property divisions. Thus, it is represented through Peckham and NUNHEAD by the alignment of back garden fences and walls.

London–Stevenage • This road left the CITY at CRIPPLEGATE, and the course is marked by REDCROSS STREET and GOLDEN LANE, Highbury Grove, HIGHBURY PARK and parts of Blackstock Road. Traces of an agger here have been found in the grounds of ALEXANDRA PALACE, and there are more substantial remains north of Potters Bar.