The Normans arrived in the Byzantine world not as enemies, but as valued mercenaries esteemed for their martial prowess. The settlement of Scandinavian raiders created the duchy of Normandy, when the region was ceded to their war leader Rollo (d. ca. 931) by the Carolingian king Charles the Simple (898–922). Rollo’s descendants mingled with the local French population to create the Normans, a people thoroughly Christian, doggedly militaristic, and unfailingly expansionistic. Norman soldiers entered Italy around the start of the eleventh century where they served as mercenaries for various Lombard princes. By the 1050s large numbers of “Franks,” as the Byzantines called them, had served as mercenaries in Byzantine armies from Syria to Bulgaria, and Normans served as part of the standing garrison of Asia Minor. In the 1040s the Normans began the conquest of south Italy, establishing several counties in the south and finally invading and conquering Sicily from the petty Muslim dynasts there by 1091. Since the late 1050s the Normans had challenged Roman interests in Italy and Robert Guiscard led a Norman invasion of the Byzantine Balkans in 1081. In the ensuing conflict the Normans defeated Alexios I Komnenos, who expelled them only with great difficulty. Two more major Norman invasions followed over the next century, and the Norman kingdom of Sicily remained a threat to imperial ambitions in the west and to the imperial core until the Hauteville Norman dynasty failed in 1194. By this time all hope for the Byzantine recovery of south Italy and Sicily had vanished, thanks to Norman power.

Organization

The Normans served under captains who rose to prominence due to birth or their fortunes in war. Minor nobility like Tancred of Hauteville, who founded the dynasty that would conquer much of Italy and Sicily, was a minor baron in Normandy and probably the descendant of Scandinavian settlers. The warriors who carved out territory within Byzantine Anatolia seem to have been either petty aristocrats or simply successful soldiers. One such Norman was Hervé Frankopoulos, who in 1057 led 300 Franks east in search of plunder and territory. After initial successes around Lake Van, he was delivered to the emperor and eventually pardoned. Thus, Norman companies were of no fixed numbers, and it seems that each baron recruited men according to his wealth and status. Norman lords in Italy raised the core of their army from men to whom they distributed lands and wealth in exchange for permanent military service. Lords were required to provide fixed numbers of troops, either knights or infantry sergeants. Other Normans served for pay and plunder, including conquered lands to be distributed after successful occupation of enemy territory. The Normans that the Byzantines encountered were a fluid group—some fought for the empire and then against it; their interests were pay and personal advancement rather than any particular ethnic allegiance. In this the Normans who warred against the Byzantines resembled the later free companies of the late medieval period—variable in numbers, generally following a capable, experienced, and charismatic commander, and exceptionally opportunistic. As a warlord’s success grew, so did his resources. Thus Robert Guiscard rose from the leader of a band of Norman robbers to be Count and then Duke of Apulia and Calabria; in 1084, following his defeat of Alexios at Dyrrachium, Guiscard marched on Rome with thousands of infantry and more than 2,000 knights, a far cry from the scores or hundreds with which he began his career.

Methods of Warfare

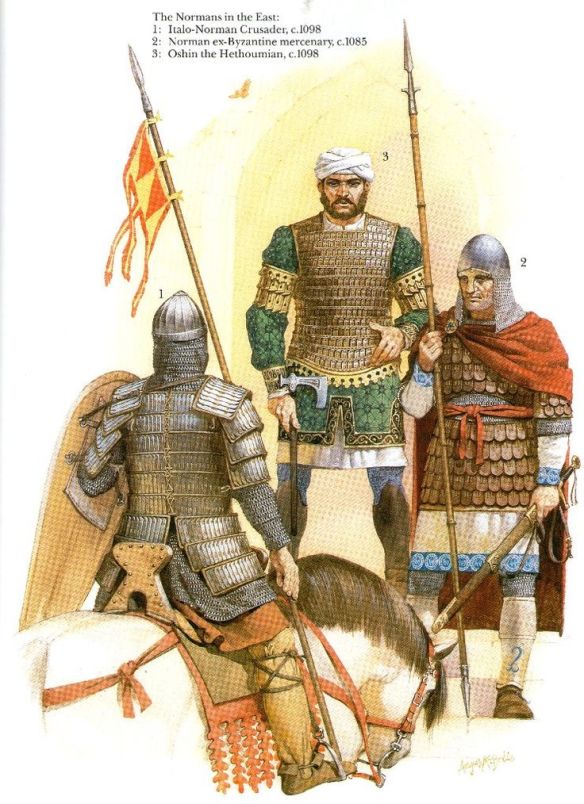

The bulk of the Norman fighting forces were infantry, but they formed a largely defensive force that operated in support of the cavalry. Norman infantry fought generally as spearmen—the Bayeux Tapestry shows many Normans on foot wearing the nasal helm and mail hauberks, but it is unlikely that the majority were so armed. Most were probably unarmored and relied on shields for protection like most of their counterparts throughout Europe. Light infantry archers fought with little or no armor, and missile troops played a role in their Balkan campaigns as well—the Byzantine commander George Palaiologos suffered an arrow wound to his head in battle at Dyrrachium in 1082, but generally the Byzantines relied on superior Turkish archery in order to unhorse the Normans and immobilize the knights. Norman knights wore heavy mail hauberks and mail chausses with in-pointed mail foot guards, which Anna Komnene noted slowed the Norman cavalry down when they were unhorsed. These mounted men carried lances and swords. The weight of their mail made them relatively safe from the archery of the day. Norman knights usually decided the course of battle; it was the shock cavalry charge delivered by the Norman knight that delivered victory in battle after battle. Unlike the Turks and Pechenegs with whom the empire regularly contended and whose weaponry was lighter and who relied on mobility, hit-and-run tactics, and feigned retreat, the Normans preferred close combat. They fought in dense, well-ordered ranks and exhibited exemplary discipline. In an era when infantry were generally of questionable quality, most foot soldiers throughout Europe and the Middle East could not stare down a Norman frontal cavalry charge. Norman horsemen punched holes in opposing formations and spread panic and disorder that their supporting troops exploited. By the end of the eleventh century, Norman prowess on the battlefield yielded them possessions from Syria to Scotland.

Byzantine Adaptation

The Byzantines avidly recruited Normans into their armies. Though critics have unfairly blamed the medieval Romans for not adapting their warfare in light of the new western techniques and technologies to which they were exposed, fully equipped and well-trained kataphraktoi could match the skill and shock power of the Norman knight. What the Byzantines of the Komnenoi era lacked were the disciplined heavy infantry of the Macedonian period and combined arms approach of mounted and dismounted archery that could blunt enemy attack and cover infantry and cavalry tactical operations. Alexios I relied on Turkish and steppe nomad auxiliaries and patchwork field armies assembled from mercenaries drawn from the empire’s neighbors. As with other intractable foes, the Byzantines relied on a combination of defense and offense—the Normans were contained in the Balkans allowing space for an imperial recovery and the time to muster new forces following the heavy defeat late in 1081 of the Roman army at Dyrrachium on the Adriatic. Alexios allied with southern Italian nobles and the German emperor Henry IV (1084–1105) who menaced the Norman flanks. The death of Robert Guiscard in 1085 removed the most serious threat to Byzantine rule since the seventh century, but Guiscard’s son, the redoubtable Bohemund, renewed war against the empire in 1107–8. Alexios had learned from his twenty years of dealing with the Norman adversary and returned to the traditional Byzantine strategies of defense, containment, and attrition. The Byzantines relied on their Venetian allies to provide naval squadrons on the Adriatic that interfered with Norman shipping and resupply, and Alexios’s forces blocked the passes around Dyrrachium; the emperor forbade his commanders to engage in a large-scale confrontation with the Normans. In the skirmishes and running battles against Norman scouting and foraging parties Byzantine archers shot the enemy mounts from beneath their riders and then cut down the beleaguered knights. Hunger, disease, and lack of money undid Bohemund, who was forced to sign a humiliating treaty and return to Italy. Thus the ages-old Byzantine principles of indirect warfare proved triumphant against a stubborn and superior enemy.