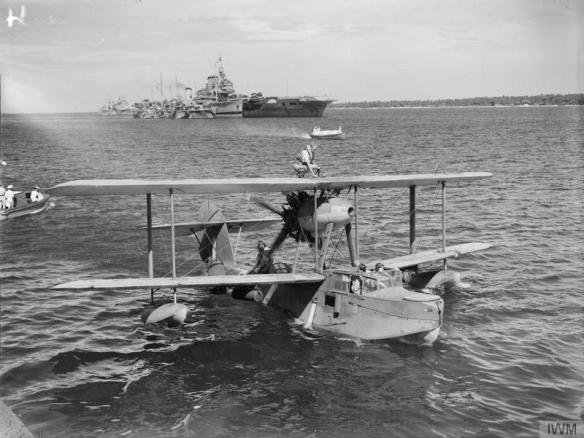

HMS WARSPITE recovers her Walrus as oilers and tenders cluster about FORMIDABLE and other ships of the Eastern Fleet.

The strategic consequences of the IJN attack on Ceylon, and the resulting exposure of the Eastern Fleet, were addressed in two joint planning staff papers dated 18 and 21 April. These drew on an updated Joint Intelligence Committee assessment, which anticipated further IJN raids and the continuing risk of a full-scale invasion of Ceylon as well as simultaneous pressure on northeast India. The key lesson the planning staff drew was that Royal Navy ship-borne air strength was greatly inferior to that of the IJN. The IJN could, therefore, exercise air superiority to command sea communications where it wished, and the Eastern Fleet was powerless to intervene. The planners judged that the first Japanese priority was to consolidate their hold on Southeast Asia and Burma, but a rapid move to drive Britain out of the war by disrupting supplies to the Middle East and India, and of Persian oil, must be tempting. SIGINT seemed to support this judgement. On 13 April, the Japanese foreign minister told the German ambassador in Tokyo that Japan was thrusting towards Ceylon and the area north of it. This thrust would extend ‘step by step’ into the western Indian Ocean. To achieve this goal, the planning staff argued, the Japanese must take Ceylon and destroy the Eastern Fleet. Safeguarding the fleet was paramount, and took precedence over holding Ceylon. The Eastern Fleet must, therefore, retreat to East Africa until it could be reinforced sufficiently to contest the central Indian Ocean on acceptable terms. The ideal target strength was five modern capital ships and seven fleet carriers, of which five and four were planned by August. In the meantime, defence of Ceylon must rely on air power.

Churchill, meanwhile, highlighted the grave risks in the Indian Ocean in letters to President Roosevelt dated 7 and 15 April. His second letter emphasised that Britain for some months could not match the naval forces the Japanese had demonstrated they were willing to deploy in the Indian Ocean. The loss of Ceylon and invasion of northeast India were real possibilities, but this would only be the beginning. There was little to stop the Japanese dominating the western Indian Ocean and undermining Britain’s whole position in the Middle East. He stressed here the consequences of losing Persian oil and the supply line to Russia. Overall, the situation was ‘more than we can bear’. He sought United States support through diversionary action in the Pacific, further reinforcement in the Atlantic to release Royal Navy units, or direct naval support in the Indian Ocean itself. This letter reflected discussion at the Defence Committee the previous day, at which General Marshall and Harry Hopkins were present.

The outcome of this Defence Committee meeting has proved controversial. The British endorsed Marshall’s proposals for an early invasion of western Europe. However, the prime minister and Brooke insisted that it was still essential to hold the Middle East, India and Australasia. A second front in Europe must not compromise these interests. The justification for their caveat has since been questioned. Brooke is accused of exaggerating the consequences that would follow Japanese control of the Indian Ocean, and demanding an open-ended commitment from the United States to prevent collapse in the Indian Ocean and Middle East. The implication is that the British leadership was engaged in deliberate deception. They had no real intention of committing to a second front at this time, but sought to keep the United States focused on ‘Germany first’, while they pursued their own interests.

It is important to look dispassionately at the threat to the Indian Ocean as it appeared at the time. Charging Brooke with exaggeration reflects hindsight, rather than a fair appraisal of the risks as Brooke must have seen them. In the wake of Nagumo’s raid, a return operation by Japan to seize Ceylon looked entirely credible. So did a concerted IJN effort across the rest of 1942, by raiders, submarines and select use of carrier task forces, to cut effective communication in the western Indian Ocean. If the Japanese pursued this option all-out, there was little the US Navy could do in the Pacific during 1942 to prevent them. From the British perspective, an IJN offensive might, at a minimum, eliminate the prospect of a British Empire material advantage in the North African campaign by the autumn. It could also drastically reduce oil supplies across the eastern theatre, with major consequences for the empire war effort, and for any United States operations mounted from India and Australia. Finally, it would severely disrupt aid on what was becoming the primary military lend-lease route to Russia, with unknowable consequences for Russia’s survival. Japan might achieve even more. Countering these risks had to be a top priority.

Nor was Britain seeking an ‘open-ended commitment’. Britain wanted American support for a limited period of two and a half months, while sufficient reinforcements were gathered to make the Eastern Fleet reasonably competitive with the maximum force the Japanese were likely to deploy. In effect, Britain’s war planners must bridge a period while key Royal Navy units were under repair, or working up, and before new construction became available. Valiant was under repair in Durban following her damage at Alexandria in December and expected to complete in June. Nelson and Rodney were working up after repair and refit. The carriers Eagle and Furious were in refit. The new battleships Anson and Howe were expected to be operational in August and October respectively. By the time the Defence Committee met again just a week later on 22 April, a target date of 30 June had been set for assembling the enhanced Eastern Fleet and the relevant forces earmarked. This fleet would have been significantly stronger than the forces available to the US Navy to hold Hawaii.

The British leadership may well have been privately doubtful that Marshall’s vision for an early second front reflected realistic understanding of the logistics and the quality of enemy opposition. Hindsight suggests they were right. They inevitably prioritised the protection of the wider empire, because it defined Britain’s status as a world power but, more important, because it provided essential war resources. Many in the United States leadership also supported Churchill’s emphasis on the Middle East, India and Australasia, for their own reasons.

In response to British pleas, the United States judged it could not help in the Indian Ocean, but it did offer limited support in the Atlantic and, most important, diversionary action was underway in the Pacific. This was the bombing raid on Tokyo led by Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle. This raid by a small force of B-25 bombers launched from the US Navy carriers Enterprise and Hornet took place on 18 April. The military impact was negligible, but the psychological effect on the Japanese military leadership was profound. It did not initiate the Midway operation, which had already been approved two weeks previously. However, it underlined Yamamoto’s conviction that the US Navy carrier force must be eliminated before other options, including further offensive action in the Indian Ocean, were contemplated. Crucially, it also caused the Japanese to add a second Midway objective – the occupation of the island. The resulting conflict of priorities would have fatal consequences. Pound, meanwhile, underlined British anxieties during a visit to Washington in late April, and received sufficient assurances from Admiral King, the new Chief of Naval Operations, to confirm the feasibility of giving significant reinforcements to Somerville.

The chiefs of staff copied the latest joint planning staff assessment to Somerville on 23 April. Its conclusion encapsulated how London saw the position in the East at this time:

If the Japanese press boldly westwards, without pause for consolidation and are not deterred by offensive activities or threats by the Eastern Fleet or American Fleet, nor by the rapid reinforcement of our air forces in North-East India, then the Indian Empire is in grave danger. The security of the Middle East and its essential supply lines will be threatened. The Middle East and India are inter-dependent.

Somerville, shocked by the ferocity of the IJN strike on the Dorsetshire force, and now aware how close he had come to disaster, agreed with the London view. He reinforced the disparity in air power in a sharp exchange with the Admiralty at the beginning of May. For daytime air strike, the Royal Navy was ‘completely outclassed’ by the Japanese, though Somerville judged that in low cloud or at night it had an advantage. He hoped by now it was appreciated that the Fleet Air Arm, ‘suffering from arrested development for many years’, could not compete successfully with an IJN carrier arm, ‘which had devoted itself to producing aircraft fit for sailors to fly in’. Pending the arrival of better aircraft, he proposed a substantial increase in fighter complement, employing deck parking and outriggers where necessary. The prime minister took a personal interest in Somerville’s proposals, which were broadly agreed, though it was recognised that achieving an adequate supply of Martlets would require high-level political lobbying in the United States.

Fleet Air Arm aircraft deficiencies were not easily solved. Despite constant British lobbying at the highest level, the flow of Martlet fighters from the United States remained barely adequate through most of 1942. It was well into 1943 before the first new strike aircraft arrived. In the meantime, Somerville’s belief that the IJN had deployed fighter-bombers led the Admiralty briefly to contemplate employing unsuitable Hurricane IIs in a similar role. Some in the Royal Navy leadership, including Pound, still struggled to understand the revolutionary nature of carrier warfare as practised by the IJN, and shortly by the US Navy. This was partly poor intelligence assessment, which continued to underestimate the number and quality of IJN aircraft deployed in their carriers and, therefore, their lead over an equivalent Royal Navy force. It also reflected their persistent belief that the IJN would deploy capital ship raiders against trade on the German Atlantic model. This led to over-emphasis on comparative capital ship strength when measuring the effectiveness of the Eastern Fleet.210 Churchill also still defaulted to the battleship as the ultimate arbiter of strength.

Nevertheless, it is wrong to imply that the Royal Navy downplayed the role of the carrier in its future force planning, and its importance in bringing the eastern war to a successful conclusion. Its commitment to the carrier as a fleet unit is evident in the extraordinary total of sixteen new light carriers of the Colossus and Majestic classes ordered in the single year 1942, when British war resources, not least shipbuilding capacity, were stretched to the limit. These highly successful ships provided two-thirds of the aircraft capacity at two-thirds of the cost of the latest Illustrious units. More important, by adopting commercial standards of construction and using commercial shipyards, they were completed much more quickly, with the first units commissioned in an average of twenty-seven months. Before the end of the year, the newly appointed Deputy First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Charles Kennedy-Purvis, was powerfully arguing that carriers represented ‘the core of the future fleet’, although Pound, still attached to the battleship, preferred the formula, ‘the carrier is indispensable’.

The few accounts of the Indian Ocean theatre in 1942 describe the Eastern Fleet, which collected at Kilindini in Kenya during April after the Ceylon raid, as an ineffective force incapable of contesting further serious IJN incursions. Its survival depended on keeping its distance until the US Navy victories at the Coral Sea and Midway rendered its existence largely irrelevant. Its status is seen, therefore, as confirmation of chronic British over-stretch, and Royal Navy inability to meet the demands of modern air warfare at sea. This picture is misleading. Kilindini did, indeed, become the primary base for the Eastern Fleet for the rest of 1942. However, Somerville continued to deploy a fast carrier force, broadly equivalent to the Force A of early April, to the central Indian Ocean on a regular basis over the next six months. He operated from, or around, Ceylon for almost 50 per cent of this period.

Furthermore, during April and May, in line with the joint planning staff recommendations on 18 April and the subsequent Defence Committee discussions, and the promises of indirect support from Washington, the Admiralty redoubled its efforts to send significant reinforcements to the Indian Ocean. By September at the latest, it intended to return an enhanced Eastern Fleet to Ceylon, with six modern or modernised capital ships and four fleet carriers. This was broadly the force planned in Moore’s December 1941 paper, but with additions. Three-quarters of the Royal Navy’s major units would be in the Indian Ocean. The Home Fleet would be reduced to a minimum, while defence of the Mediterranean would rest on air power and light forces. The Ceylon bases were to be upgraded in the interim, with a Ceylon air group of nine Royal Air Force squadrons, including a Beaufort torpedo force.

These were, by any standard, serious forces, which demonstrated the continuing naval priority accorded to the eastern theatre. Both the initial fast carrier force and the Ceylon air group available in May took time to achieve what Somerville felt was an acceptable operational standard, but the enhanced fleet planned for the autumn could have contested the central Indian Ocean with every prospect of success. The Admiralty also recognised that this enhanced Eastern Fleet would be a sustained commitment with first call on aircraft carriers for the foreseeable future. At the end of 1943, it planned four fleet carriers and six escort carriers deployed in the Indian Ocean, with one fleet carrier and sixteen escort carriers allocated to the Home Fleet, and no carriers at all in the Mediterranean.

The Fleet Air Arm aircraft limitations highlighted by Somerville would have persisted in the enhanced Eastern Fleet carrier force. However, the Royal Navy technological lead in radar and VHF radio, and their exploitation, substantially compensated for the continuing disparity in aircraft numbers and quality. The training and experience shortfall so evident to Somerville in April would also have been addressed. If Indomitable, Formidable and Illustrious had all remained in the Indian Ocean through 1942, these three carriers alone would have deployed some eighty fighters and sixty strike aircraft between them in September. The fighters would have included fifty Martlets. This Royal Navy fighter strength would be comparable to that deployed by the three US Navy carriers at Midway in June, but the Royal Navy had better radar detection and direction. It would have posed a formidable defence to any likely IJN air strike. Sixty ASV-equipped Albacores and Swordfish would have been an equally formidable night strike force. Furthermore, the disparity between IJN and Royal Navy numbers was reducing through 1942, owing to the increasing difficulty the IJN had in maintaining its frontline strength. The IJN Midway strike force only had 151 aircraft.

Proof that the Royal Navy could conduct advanced multi-carrier operations against the most sophisticated air opposition by the second half of 1942 is demonstrated by its performance in Operation Pedestal, the convoy run to relieve Malta in August. Pedestal involved four carriers, including Somerville’s Indomitable, transferred from the Indian Ocean. The three carriers charged with air defence deployed seventy-two fighters against an estimated Axis force of 650 aircraft employed against the convoy during a three-day running battle between 11 and 14 August. Although convoy losses, both merchant vessels and naval escort, were high, the majority were caused by submarine and E-boat action, not air attack, where the defence proved effective. The two most intense days of air attack on 11 and 12 August only damaged one of the merchant vessels, their primary target, although they achieved minor damage to Victorious and more serious damage to Indomitable. This reflected excellent fighter defence from the carriers, with sophisticated use of radar and aircraft direction, and intense anti-aircraft fire from a well-constructed screen. Indeed, on the morning of 12 August, 117 Italian aircraft and fifty-eight German achieved just the one ineffective hit on the carrier Victorious. Never before had the Axis air forces used so many aircraft for so little result. Despite the losses, the convoy was a strategic success. Enough supplies got through to enable Malta to survive, with important implications for the eastern theatre. As noted previously, it is doubtful whether either the IJN or US Navy could have carried out a comparable operation, and in such a complex multi-threat environment, against an equivalent level of air attack at this time.

While established history has underestimated the true potential of the Royal Navy in the Indian Ocean during 1942, it has overestimated that of the IJN. Joint planning staff assessments of mid-April, arguing that the IJN could achieve air superiority where it wished, at least in the eastern half of the Indian Ocean but potentially further west too, were only true within narrow limits. It was one thing to conduct raids like Operation C. It was another to mount the sustained aerial effort necessary to capture Ceylon, or to provide the logistic back-up required for deep operations to challenge the Eastern Fleet and disrupt communications along the African coast and into the Persian Gulf. The First Air Fleet was not capable of any immediate follow up to Operation C. After six months of intense operations, it required maintenance and replenishment. More seriously, the IJN was struggling to maintain its frontline air strength. Six months into the war, and immediately before the Midway campaign, IJN aircraft complements, especially in the carrier force, were not just ‘fraying around the edges’, but were ‘downright awful’.

On 7 December 1941 aircraft strength within the overall carrier force was 473, with just twenty-two reserves. By the end of May, naval fighter production had kept pace with losses, with a net gain over this period of 121. However, production of the two main carrier attack aircraft, the Nakajima B5N2 Type 97 torpedo bomber and Aichi D3A1 Type 99 dive-bomber, was woeful, with just 143 aircraft built against losses of 273, a net deficit of 130. Incredibly, no Type 99s were produced during the four months December 1941 to March 1942. The available frontline carrier attack force by the time of Midway had therefore declined a staggering 40 per cent. Neither Nakajima nor Aichi had adequately prepared for wartime output, and both companies were focusing their attention on successor aircraft at the expense of existing types. IJN land bomber strength was better. Production almost kept pace with losses over the first six months of the war, with a net deficit of just seventeen, easily covered by reserves. However, total IJN land bomber strength at the start of the war was just 339 aircraft with 106 reserves. This was a small force to cover the numerous commitments the IJN faced in mid-1942.