Japanese 6th Fleet Headquarters at Kwajalein had come up with a further innovative use for submarines that had already been employed in the attack on Pearl Harbor. The seven submarines of 1st Submarine Squadron were given a new task, and were to bring the war in the Pacific to America’s doorstep. Joined by the I-10 and I-26 from the original Pearl Harbor Reconnaissance Unit, Vice-Admiral Shimizu ordered the nine submarines to pursue the enemy eastwards and to patrol off the American west coast. The American public and military were already jittery following the audacious Japanese aerial and submarine attack on Hawaii, and rumours abounded of the likely next move by the Japanese towards the mainland of the United States. Perhaps an enemy landing on the lightly defended Pacific coasts of California or Oregon was a distinct possibility? The Japanese knew of American invasion fears and the redeployment of Japanese submarines close to these very coasts would hopefully have an adverse effect on civilian morale far outweighing any strategic or military impact they would have been able to make with the limited resources placed at their disposal.

Each of the eventual eight Japanese submarines that moved into position was ordered to interdict American coastal shipping by lying off the major shipping lanes, such as those located off Los Angeles and San Francisco. Rear-Admiral Sato, commander of 1st Submarine Squadron, was aboard his flagship, the I-9, directing operations at sea. It was expected that each skipper would make each of his seventeen torpedoes tell, and 6th Fleet had ordered them to only expend one torpedo per enemy ship. The submarine captains had also been ordered to expend all of the ammunition for their submarine’s 140mm deck-gun before returning to base. This would be achieved by supplementing the limited supply of torpedoes carried onboard by blasting merchant ships to pieces with the submarine’s artillery piece, and then turning the gun on vulnerable American coastal installations. It was a plan intended to spread fear and panic along the huge Pacific Ocean coast of the United States, a plan to set the inshore waters and shoreline ablaze.

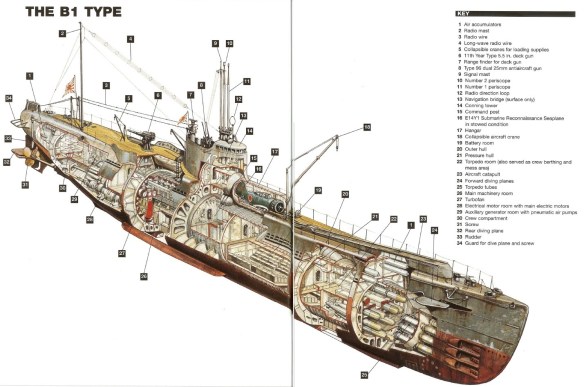

The I-17 was a Type-B1 Japanese fleet submarine skippered by Lieutenant-Commander Kozo Nishino, an example of the most common and numerous class of submarine employed by Japan during the Second World War. Between 1940 and 1943 twenty were constructed, earlier examples such as the I-17 being equipped with the ingenious Yokosuka E14Y1 floatplane used for reconnaissance. A watertight hanger was fitted aft of the conning tower, the aircraft being launched by means of a catapult and ramp built into the submarine’s deck. Each B1 submarine was 356.5 feet long with a top speed on the surface of 23.5 knots, or 8 knots submerged and running on electric motors. Prior to the introduction of nuclear-powered submarines in the 1950s the vessels that fought in the Second World War were essentially submersibles rather than true submarines. Japanese, German, British and American submarines, and the submarines of every nation able to maintain undersea fleets, were all limited by their central power sources. Submarines at this stage were powered by diesel engines while they were at the surface, making them relatively fast and ideal platforms to launch anti-commerce and anti-warship attacks from, especially when cloaked by the cover of darkness. The power of large Japanese diesels fitted to many types of their submarines produced enough speed to allow the vessels to keep pace with the surface battle fleet – which remained a primary consideration of Japanese submarine designers throughout the Second World War. If forced below the surface of the water, or if attempting a submerged attack, the submarine was powered by electric motors running off cumbersome and space consuming batteries. The submarine immediately lost its speed and agility beneath the sea, and could only remain submerged while the air aboard remained breathable for the crew. The Japanese would not be able to match the Germans in advanced submarine design during the Second World War to overcome the twin problems of increasing underwater speed and staying semi-permanently submerged during patrols, and their submarine force would pay a heavy price as Allied anti-submarine technology developed exponentially as the war progressed. The Germans went some way to overcoming the problems of extended periods spent below the surface and running on electric motors by the incorporation of a Dutch design known as the snorkel. Basically, a submarine was fitted with a large mast that could be raised until the head was above the surface of the water, the submarine remaining submerged. Air would be sucked into the snorkel head, allowing the diesel engines to be run while the submarine was submerged, and the boat aired, theoretically enabling a German U-boat to conduct its patrol entirely submerged and therefore rendering it less vulnerable to Allied attacks. Fitted to most late-war German U-boats the snorkel often malfunctioned due to poor construction or components, and if waves splashed over the snorkel head the diesel engines would suck air from inside the U-boat, causing the crew great discomfort, especially to their ears and occasionally causing unconsciousness. Allied warships could also locate the snorkel head in the same way as a periscope mast, and the submarine would be attacked. Japanese submarines were not fitted with this technology, even though the Germans gave the Japanese detailed plans of the apparatus as part of ongoing German-Japanese trade and military technology exchanges between 1942 and 1945.

If a Type-B1 submarine was run at full speed on the surface the skipper would have rapidly used up his available diesel fuel, severely curtailing the boats operational potential, so a top speed was simply the boats potential power. Rather, a sensible skipper would be able to take his B1 on a round-trip patrol of approximately 14,000 nautical miles at a conservative 16 knots without requiring a single refuelling pit stop. This would make the B1 submarine the ideal platform with which to sail across the Northern Pacific to the west coast of the United States, and bring the war to America’s doorstep. Added to the potency of the B1’s great range was a 140mm deck-gun designed to assist a skipper in sinking ships. The deck-gun fired armour piercing anti-ship ammunition, designed to penetrate the steel hulls of ships and explode within. Pump a sufficient quantity of these cheap shells into a merchant ship and the result was a foregone conclusion, and just as effective as a torpedo. It was a more economical option than expending one of the seventeen torpedoes carried aboard the B1 through one of the boat’s six torpedo tubes. Ninety-four officers and men crewed the B1, including two pilots and two observers to man the Yokosuka floatplane (one pilot and observer acting as a reserve crew).

Although the B1 was not the biggest submarine type employed by the Imperial Navy, the Japanese nonetheless cornered the market in producing large submarines during the Second World War. The B1 was bigger, better armed, quicker and with a greater range than the closest comparable German U-boat type. For example, the Type IXC U-boat had given the Germans the ability to take the war to the east coasts of the United States, Canada and all around South Africa by 1942 and could motor an impressive 11,000 nautical miles at 12 knots before requiring refuelling. However, the Type IXC, at 252 feet long, was nearly 100 feet shorter than the Japanese B1, and was armed with fourteen torpedoes and a 105mm deck-gun and anti-aircraft weapons. Importantly, although German U-boats were smaller, had a shorter range and carried less munitions than their Japanese counterparts, they were quicker to submerge and were progressively equipped with superior technology such as radar detectors and snorkels that increased their survivability. The fundamental difference between a Japanese submarine and a German U-boat was not so much the technical specifications and technologies utilized in creating them, but the method in which they were employed. The Japanese viewed submarines as essentially fleet reconnaissance vessels to replace cruisers in that role, whereas the Germans saw submarines as the tool with which to sink millions of tons of enemy merchant shipping in order to reduce the industrial/military output of their opponents, and create hardship on the enemy home front.

Nishino aboard the I-17 was proceeding on the surface in the pre-dawn darkness fifteen miles off Cape Mendocino, California on 18 December 1941, lookouts armed with powerful binoculars patiently scanning the barely discernable horizon on all points of the compass, and studying the sky in case of air attack. They were quiet, speaking only briefly in hushed tones, using their ears as well as their eyes to search out engine noises above the rhythmic reverberations of the I-17’s twin diesels as they lazily pushed them through the dark Pacific waters. The eerie red glow of low night lighting crept up the conning tower ladder from the control room below, etching the faces of the Japanese submariners into fixed masks of concentration and anticipation. Suddenly, as the first glow of dawn began to rise on the eastern horizon a lookout let out a guttural exclamation. His arm shot out in the direction of the approaching ship, a compass bearing relayed to the helmsman below, as Nishino ordered his vessel closed up and made ready for action. In normal circumstances a submarine captain would attack his intended target with a spread of torpedoes, a staggered shot that would fan out to intercept the intended target(s) after calculations of the speed and direction of the prey had been computed into the attack plot. Nishino was under strict orders to only expend a single torpedo per enemy ship, which did not give him much latitude for attack, and meant that the Japanese submarine would have to move up very close to the target ship to be sure of not wasting the valuable mechanical fish. Nishino decided that the best method of attack as the merchant ship hove into view was the employment of the deck-gun for the time being. If he could inflict sufficient damage to the freighter with his gun, enough to stop her, he could then decide whether to finish her off with more armour-piercing shells or close in for a single torpedo strike against a static target. The I-17, however, was rolling heavily in the swell as crewmen busily prepared the deck-gun for immediate action, manhandling shells from the gun’s ready locker, ramming home a round with a solid thump as the breech was closed and the gun commander awaited the signal from the bridge to open fire.

The ship in the gunners’ sights was the American freighter Samoa under the command of Captain Nels Sinnes, who was about to be abruptly awoken by the report of a submarine close by. The Samoa had already sustained damage, but not from enemy action. She had been caught by a heavy storm which had washed away one of the ship’s lifeboats. The Samoa also had a noticeable list to port, as the engineers had been shifting water in the ballast tanks following the battering from the ocean. The pronounced list, and the remnants of the wooden lifeboat hanging from its launching davits, would be providential in saving the ship from the attentions of the I-17 in the minutes that followed.

Captain Sinnes quickly dressed and, grasping a life jacket, ordered his crew to muster at their lifeboat stations. The sailors frantically stripped the covers from the open boats and began swinging them out on their davits ready to launch when the Japanese opened fire. Five times the I-17’s deck-gun barked, its flat high velocity report sounding out across the empty sea, the armour-piercing shells tearing towards the defenceless Samoa. Four missed to fountain in the choppy ocean, the Japanese gunners pitching hot, steaming shell cases overboard as others fetched fresh shells from the ready locker. The fifth shell exploded above the Samoa with an ear-splitting crack, white-hot shrapnel pummelling the deck. The Japanese submarine was rolling erratically on the disturbed sea, making it difficult for the gunners to accurately target the American ship, and they were reduced to flinging shells in the general direction of the enemy vessel and hoping for a lucky strike. Commander Nishino quickly tired of this pointless shooting and ordered a surfaced torpedo attack, the fish leaving the I-17’s bow with a hiss of compressed air and a trail of bubbles, quickly crossing the barely seventy yards that separated hunter and prey. In the early dawn light it appeared to the crews of both vessels to be a foregone conclusion.

Incredibly, as the crew of the Samoa braced for impact and a thunderous explosion, nothing happened. The torpedo passed clean underneath the merchant ship. The blind torpedo cruised on a short distance and then erupted in a massive tumult of water, smoke, fire and flying shrapnel. Fragments of the torpedo thumped harmlessly onto the Samoa’s deck, the I-17 a low black shape that drifted ominously closer to the American ship. Officers aboard the submarine attempted to assess the damage the torpedo, which they erroneously assumed had struck the Samoa, had caused. Now perhaps no more than forty feet from the side of the merchant ship, the early morning gloom frustrated their efforts. Still the I-17 closed with the Samoa, coming to within fifteen feet of the hull. Someone aboard the I-17, according to the Americans, yelled out in English ‘Hi ya!’ Captain Sinnes yelling back ‘What do you want of us?’ when he already knew the answer. From his position alongside the Samoa Nishino observed the vessel’s heavy port list and assumed she was doomed. The I-17 slowly pulled away and disappeared. Nishino instructed his radio operator to report a successful kill to the I-15, coordinating submarine operations from her position off San Francisco.

The Samoa arrived safely in San Diego on 20 December after her close encounter, saved by storm damage and the poor early dawn light. On the same day Nishino redirected his submarine to its original position off Cape Mendocino, some twenty miles from the American coast. The crew of the I-17 awaited another target of opportunity, buoyed up by their apparent first successful sinking of an enemy vessel of the mission. The day wore on with no sightings of American merchant ships, until, bathed by early afternoon winter sunshine, the lookouts were once more laboriously scanning the horizon and biding their time. Nishino made no attempt to disguise his presence so close to the coast, believing he had little to fear from American naval or air forces still reeling from the devastating attack on Pearl Harbor fourteen days previously. Just after 1.30 p.m. the sight of the oil tanker Emidio heading towards San Francisco rewarded Nishino’s patience. The Emidio was only carrying ballast, returning empty from Seattle’s Socony-Vacuum Oil Company facility.

Captain Clark Farrow reacted as swiftly as he could to the report of a submarine gaining on his ship. Nishino aboard the I-17 ordered full power, the big diesels churning confidently ahead, the submarine making fully 20 knots, her exhausts trailing blue clouds of fumes into the clear Pacific air. Captain Farrow lightened his ship, dumping ballast that made the Emidio steady in the water but painfully slow, frantically ringing ‘full speed ahead’ on the engine room telegraph. The I-17 cut through the water, closing rapidly on the Emidio’s stern, crew racing to man the deck-gun as Nishino manoeuvred his boat for the attack. It was imperative that the American ship be prevented from radioing for assistance, and therefore reporting Nishino’s position to United States forces. Captain Farrow was already a step ahead of Nishino, however, as he had ordered his radio operator to send the following short Morse message: ‘SOS, SOS: Under attack by enemy sub.’

Nishino ordered the gun crew into action, the first shell exploding close to the Emidio’s radio antenna, blowing the fragile communication mast into useless scrap. In rapid succession the submarine’s gun banged twice more, the shells screaming across the ocean into the defenceless Emidio, a lifeboat exploding into smouldering matchwood. Ashore, the US Army Air Corps were already scrambling a pair of medium bombers following the receipt of the Emidio’s distress signal and position, in the hope of destroying the Japanese submarine. Captain Farrow realized his ship was doomed, as the bombers would take some time to arrive, and he ordered the engines stopped. Meanwhile, the plucky radio operator had managed to restore communications with the shore by erecting a makeshift antenna. A white flag was hastily run up a mast and the tanker gradually slowed. The crew worked feverishly to swing out the remaining lifeboats while under constant shellfire from the I-17, Nishino ignoring the white flag and refusing to give the merchant seamen time to depart in the boats. It was not long before another shell found its mark, blowing three unfortunate crewmen into the water as it ploughed into their lifeboat. Twenty-nine crewmen were crowded aboard the lifeboats and pulled hard on the oars in an attempt to get clear of the Emidio, while four men, including the resourceful radio operator, remained aboard the ship, perhaps from a refusal to give up the vessel, or out of ignorance of the order to abandon ship issued by the captain.

On board the I-17 lookouts had reported two black dots approaching from the mainland, which could only mean aircraft. Nishino ordered the bridge cleared, the submariners hastily clattering down into the pressure hull, securing the hatches as the submarine blew its tanks and slid beneath the waves in a swirl of white water. The Emidio’s remaining crewmen now turned their eyes skyward as the American bombers roared in low over the stricken merchantman. The two aircraft circled the spot where the I-17 had a moment before submerged, eventually releasing a single depth charge. The I-17 lurched violently as the depth charge detonated, but it was not close enough to cause the submarine any damage. Perhaps realizing that the American aircraft lacked the wherewithal and experience to launch a more devastating and coordinated anti-submarine attack Nishino did the opposite of most submarine skippers in his position. Ordering the I-17 to periscope depth Nishino swiftly relocated the fully stopped Emidio. Orders were issued to partially surface the boat, and a torpedo was launched at the stationary American ship 200 yards distant. The torpedo ran true, impacting in the Emidio’s stern and detonating inside the ship with a massive blast of fire, smoke and debris. The Emidio lurched over as the engine room rapidly filled with freezing seawater. The torpedo claimed two of the four crewmen who had not vacated the ship earlier, and a third was injured. The radio operator, topside in his shack, frantically transmitted ‘Torpedoed in the stern’ before throwing himself clear of the ship into the sea. The surviving engineer, though wounded, also managed to struggle clear of the Emidio, and along with the radio operator he was plucked to safety by the small flotilla of lifeboats standing off the tanker.

The I-17 slipped once more beneath the waves as the two American bombers roared in to resume their ineffectual attack. Another depth charge plummeted into the sea and detonated in a giant plume of white water, concentric circles created by the sonic force of the explosion pushing out from the epicentre. The I-17 escaped damage once more and motored quietly away from the scene, sure again of a confirmed kill.

The Emidio, though grievously wounded and abandoned by her crew, drifted off with the current. Lost for several days from human eyes, this Second World War Mary Celeste eventually ground up against jagged rocks opposite Crescent City, California, over eighty miles from her encounter with the I-17. As for her crew, their ordeal was to be sixteen hours in open boats and battling through an unsettling rainstorm before rescue by the US Coast Guard lightship Shawnee located off Humboldt Bay.

The I-23, another Type-B1 Japanese submarine with orders to sink unescorted American merchant ships, was active at the same time as the I-17 was attempting to sink the tanker Emidio. Constructed at the Yokosuka Navy Yard, the I-23 had entered service in September 1941. She was just in time to play a crucial part in ‘Operation Z’, the submarine contribution to the Japanese victory at Pearl Harbor. On 13 December the I-23 began her relocation from the waters off Hawaii for the west coast of the United States.

On 20 December the I-23 was approximately twenty miles off Monterey Bay, California, and with a target in sight. The American tanker Agwiworld, a 6,771-tonner belonging to the Richmond Oil Company was the Japanese target. Like a fighter pilot swooping down on a hapless rookie opponent, Lieutenant-Commander Shibata approached the oblivious Agwiworld with the early afternoon sun behind his boat, a classic attack from out of the sun. Coupled with a heavy swell the big Japanese submarine’s approach behind the tanker was unobserved. The first the Agwiworld and her captain, Frederick Goncalves, knew of the presence of the Japanese submarine was the thump of the impact and explosion of a 140mm armour-piercing shell in the ship’s stern. The I-23 moved into a firing position to enable her deck-gunners to blast the tanker to scrap. However, due to the rough conditions, the Japanese sailors experienced difficulties loading and aiming the deck-gun. The I-23’s deck was awash as the boat rolled and pitched in the swell. Captain Goncalves did everything he could to make the Agwiworld as difficult a target as possible to hit, zigzagging through the whistling shells, probably eight or nine of them, before the I-23 was seen to submerge. Commander Shibata had clearly lost interest in his prey. The heavy seas and the fact that in order to achieve a good attacking position he would have had to have driven the I-23 harder would have risked the lives of his gunners, who could have been swept overboard. A further factor which precluded a more determined assault on the tanker originated in the submarine’s own radio room. The operator alerted his captain to the fact that the enemy ship had reported the Japanese submarine’s attack to the US Navy, and assistance in the form of anti-submarine assets were undoubtedly on their way.

Shibata and the crew of the I-23 were frustrated as they departed from the scene of their first attack on an American ship to search out further prey. Some time later Shibata encountered the 2,119-ton American merchant ship Dorothy Phillips. Employing an identical method of attack as that used against the Agwiworld, gunners again pumped high velocity armour piercing rounds into the hapless steamer. Although the I-23 successfully disabled the Dorothy Phillips’s steering by wrecking the ship’s rudder with a shell strike, a torpedo attack was not pressed home, presumably because the sea conditions were still unfavourable. Nevertheless, the Dorothy Phillips eventually ran aground so Shibata had scored a victory of sorts.

Lieutenant-Commander Kanji Matsumura was an experienced submarine skipper, having previously commanded the RO-65, RO-66 and RO-61 before commissioning the I-21 into service on 15 July 1941. As with the other boats assigned to operations along the United States west coast, the I-21 was formerly part of the submarine task group that made up an element of ‘Operation Z’. On 9 December the submarine I-6 had reported a Lexington-class aircraft carrier and two cruisers heading north-east. The Japanese were well aware that although they had scored a notable victory against the US Pacific Fleet’s battleship squadron they had failed to sink or damage a single American aircraft carrier. It was imperative that American carriers be sunk or damaged wherever found for the Japanese themselves had already demonstrated the power of naval aviation in this new conflict, and the days of the big-gun battleship appeared to be numbered. Vice-Admiral Shimizu at 6th Fleet Headquarters at Kwajalein, on receiving the intelligence report from the I-6, immediately ordered all submarines not involved with the launching of the midget submarines during the Pearl Harbor operation, known as the Special Attack Force, to proceed at flank speed and sink the American carrier. The I-21 was included in Shimizu’s force sent to intercept the vessel later identified as the USS Enterprise, but her progress was hampered by problems with the submarine’s diesel engines and electrics. Carrier-based Douglas SBD Dauntless aircraft spotted the I-21 on the surface on a number of occasions, necessitating Matsumura to crash-dive. Matsumura became increasingly fed up with constantly being forced beneath the waves by patrolling American aircraft. He decided upon a bold course of action – to remain surfaced and take on the enemy aircraft with his anti-aircraft armament. Motoring on the surface at 1 p.m. on the afternoon of 13 December a lone Dauntless attacked the submarine from the port side, but the accuracy of the Japanese anti-aircraft barrage caused the pilot to abort his attack run and go around for a second attempt. Diving towards the port side of the submarine again the American aircraft released a single bomb which slammed into the sea close to the I-21, but which failed to detonate.