Brought to France under the cover of canvas sheets, the first British tanks entered battle against the Germans in September 1916. In his book, Tanks In Battle, Colonel H.C.B. Rogers describes the supplies that were carried into action in the British tanks: “Rations for the first tank battle consisted of sixteen loaves of bread and about thirty tins of foodstuffs. The various types of stores included four spare Vickers machine-gun barrels, one spare Vickers machine-gun, one spare Hotchkiss machine-gun, two boxes of revolver ammunition, thirty-three thousand rounds of ammunition for the machine-guns, a telephone instrument and a hundred yards of cable on a drum, a signalling lamp, three signalling flags, two wire cutters, one spare drum of engine oil, two small drums of grease and three water cans. Added to this miscellaneous collection was all the equipment which was stripped off the eight inhabitants of the tank, so that there was not very much room to move about.”

The training of the crews that went to war in these early tanks had been sub-standard and there had been no instruction in cooperation between the tanks and the infantry. The only point of agreement between the two arms was that the tanks ought to reach their first objective five minutes ahead of the infantry forces and that the primary task of the tanks was to destroy the enemy strongpoints which were preventing the advance of the infantry.

In their initial combat action, it was intended to deploy forty-nine British tanks, but only thirty-two were able to take part. Nine of these suffered breakdowns, five experienced “ditching” (becoming stuck in a trench or soft ground) and nine more couldn’t keep up the pace, lagging well behind the infantry. But the remaining nine met their objective and inflicted severe losses on the German forces. While accomplishing less than had been hoped for, this first effort of the British tank force produced an important and unanticipated side effect. Those tanks that reached the enemy line made a powerful impression on the German troops facing them, causing many to bolt in fear even before the tanks had come into firing range.

Shrieking its message the flying death Cursed the resisting air,

Then buried its nose by a tattered church,

A skeleton gaunt and bare.

The brains of science, the money of fools,

Had fashioned an iron slave

Destined to kill, yet the futile end

Was a child’s uprooted grave.

—The Shell by Private H. Smalley Sarson

When the war is over and the Kaiser’s out of print, I’m going to buy some tortoises and watch the beggars sprint; When the war is over and the sword at last we sheathe, I’m going to keep a jelly-fish and listen to it breathe.

—from A Full Heart by A.A. Milne

For it’s clang, bang, rattle,

W’en the tanks go into battle,

And they plough their way across the tangled wire,

They are sighted to a fraction,

When the guns get into action,

An’ the order of the day is rapid fire; W’en the hour is zero Ev’ry man’s a bloomin’ ’ero,

W’atsoever ’is religion or ’is nime,

You can bet yer bottom dollar W’ether death or glory foller,

That the tanks will do their duty ev’ry time.

—from A Song of the Tanks by J. Dean Atkinson

The following passage from the book Iron Fist by Bryan Perrett describes operational conditions for the crew of the early British tanks in France around the midpoint of the First World War: “Such intense heat was generated by the engine that the men wore as little as possible. The noise level, a compound of roaring engine, unsilenced exhaust on the early Marks, the thunder of tracks crossing the hull, weapons firing and the enemy’s return fire striking the armor, made speech impossible and permanently damaged the hearing of some. The hard ride provided by the unsprung suspension faithfully mirrored every pitch and roll of the ground so that the gunners, unaware of what lay ahead, would suddenly find themselves thrown off their feet and, reaching out for support, sustain painful burns as they grabbed at machinery that verged on the red hot. Worst of all was the foul atmosphere, polluted by the fumes of leaking exhausts, hot oil, petrol and expended cordite. Brains starved of oxygen refused to function or produced symptoms of madness. One officer is known to have fired into a malfunctioning engine with his revolver, and some crews were reduced to the level of zombies, repeatedly mumbling the orders they had been given but physically unable to carry them out. Small wonder then, that after even a short spell in action, the men would collapse on the ground beside their vehicles, gulping in air, incapable of movement for long periods.

“In addition, of course, there were the effects of the enemy’s fire. Wherever this struck, small glowing flakes of metal would be flung off the inside of the armor, while bullet splash penetrated visors and joints in the plating; both could blind, although the majority of such wounds were minor though painful. Glass vision blocks became starred and were replaced by open slits, thereby increasing the risk, especially to the commander and the driver. In an attempt to minimise this, leather crash helmets, slotted metal goggles and chain mail visors were issued, but these were quickly discarded in the suffocating heat of the vehicle’s interior. The tanks of the day were not proof against field artillery so that any penetration was likely to result in a fierce petrol or ammunition fire followed by an explosion that would tear the vehicle apart. In such a situation the chances of being able to evacuate a casualty through the awkward hatches were horribly remote.

“Despite these sobering facts, the crews willingly accepted both the conditions and the risks in the belief that they had a war-winning weapon.”

A British Army corporal said they looked like giant toads. The specter of nearly 400 enemy tanks emerging from the early morning ground fog and mists of Cambrai in north-eastern France on 20 November 1917 must have impressed all who saw it. After years of stalemate and staggering attrition, this first use of massed tanks in warfare was the turning point. British armored commanders had awakened to the possibilities of the tank when imaginatively and skillfully utilized.

For most of 1917 the Allies on the Western Front had been bogged down in their trenches, unable to breach the German defenses. Now in November, the tank commanders saw an opportunity to break the cycle of despair and hopelessness that hung over the Allied armies. They proposed a massive tank raid to be launched against German positions near the town of Cambrai. They liked the prospects. The terrain of the attack was gently rolling, well-drained land. As their plan called for surprising the Germans with a fast and relatively quiet approach, there was to be no conventional softening-up artillery bombardment in advance of the raid. The commanders had intended that the great tank force would arrive quickly, inflict maximum damage and get out fast, having completed their task in three hours or less. They had presented their plan to Sir Douglas Haig, the British Commander-in-Chief on the Western Front, in August when he was incurring catastrophic losses fifty miles to the north of Cambrai in the swamps of Passchendale. At the time, the optimistic Haig was still looking for a victory and shelved the Cambrai idea. But by the autumn his Passchendale ambitions had sunk in the mud there and he was forced to accept the proposal of his tank men.

The plan called for the great mass of tanks to force a breakthrough between the two canals at Cambrai, capture the town itself as well as the higher ground surrounding the village of Flesquieres and the Bourdon Wood. They were then to roll on towards Valenciennes, twenty-five miles to the northeast. The tanks were carrying great bundles of brushwood which would be used to fill in the trenches that they would encounter when crossing the German defenses of the Siegfried Line. It was intended that the tanks would advance line abreast while the accompanying infantry troops would follow in columns close behind to defend against close-quarters attacks.

Deception and diversion were employed by the British in the days leading up to the attack. Dummy tanks, smoke and gas were all used to fool the Germans, and the men and equipment that would be involved in the attack were moved up entirely by night and kept in hiding by day. All 381 tanks allocated for the attack advanced toward Cambrai along a six-mile front.

British planning and attention to detail had been thorough and fastidious, but they had failed to factor in the possibility of one of their own commanders, a General Harper of the 51st Highland Division, deviating from the plan. It seems that Harper had doubts about the ability of the new-fangled tanks to breach the Siegfried Line as quickly as the planners required. On the day of the attack Harper delayed sending his tanks and infantry troops forward until an hour after the rest of the force had left. The delay allowed German field artillery to be positioned with disastrous results for some tank crews. Five burned-out tank hulls were found after the action. Elsewhere along the tank line, however, the armor and infantry had moved swiftly through the German lines, advancing five miles to Bourdon Wood by noon. It had been a brilliant achievement for the British tank crews.

The push continued the next day with the British taking Flesquieres and advancing a further 17 miles. In the next nine days, they won and lost the village of Fontaine-Notre Dame and the surrounding area several times. Then, on 30 November, the Germans counterattacked. Like the British, they struck without the usual initial artillery bombardment, hiding behind heavy gas and smoke screens. The British troops, exhausted by their recent effort, were forced to retreat from the rapidly advancing German forces and in just a few days had to relinquish all of their gains. In the action, the Germans took 6,000 prisoners. Blame for the defeat fell on everyone except those actually responsible—the commanders. There was concern in Whitehall that pointing the finger at their Army commanders would crush the faith of the British people in their military leadership. Still, the British had learned the valuable lesson of how effective tanks and artillery could be when properly employed in concert.

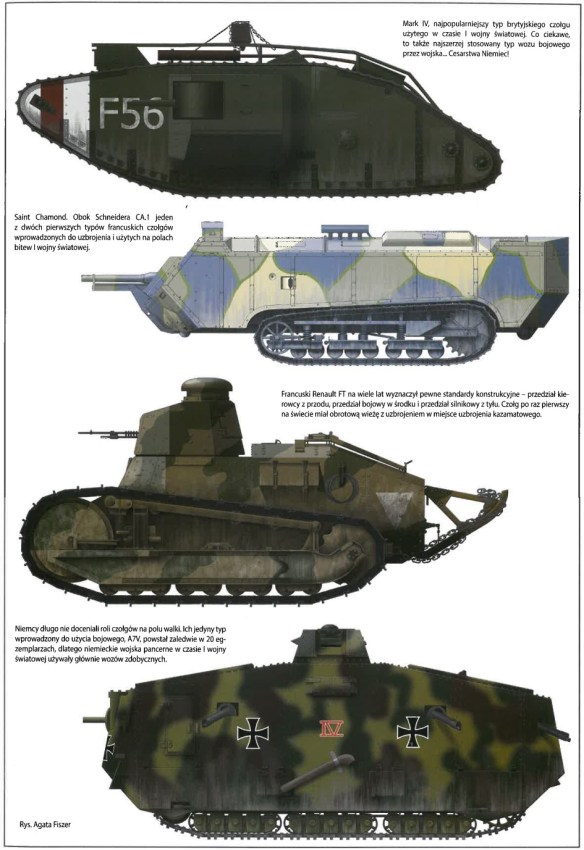

The German offensive of March 1918 began on the 21st and saw the first appearance of their tanks in battle. Designed early in 1917, the A7V was much larger and heavier than the British heavy tank of the day. It weighed thirty-three tons and was operated by a crew of eighteen. The armament consisted of one forward-mounted 57mm gun (roughly equivalent to the British six-pounder) and six machine-guns positioned at the sides and the rear. The maximum armor thickness was 30mm enabling the front of the tank to resist direct hits from field guns at long range, but the overhead armor was too thin to provide much protection. The fitting of the armor plating was such that the hull was very susceptible to bullet splash. The tank’s power came from two 150 hp Daimler sleeve-valve engines. Sprung tracks allowed the vehicle to achieve eight mph on smooth and level ground, a high speed for the time. However, the design and the low ground clearance resulted in relatively poor cross-country performance. The Germans built only fifteen A7Vs. In their initial venture into combat, four of the German tanks were used together with five captured British Mk IVs. One month later, thirteen A7Vs participated in the capture of Villers-Brettoneux and in this action the enemy tanks had the same psychological effect on the British infantry as their tanks had had earlier on their German counterparts. Tanks broke the opposing lines.

Shortly after the German success at Villers-Brettoneux, the world’s first tank-versus-tank action took place in the same neighborhood. In the early morning light, one male and two female Mk IVs were ordered forward to stem the German penetration. Though some of the British tank crew members had suffered from gas shelling, they all advanced and soon sighted one of the A7Vs. The machine-guns of the two females were useless against the armor of the German tank and both were put out of action. But the male was able to maneuver for a flank shot and scored a hit causing the German tank to run up a steep embankment and overturn. Two more A7Vs then arrived and engaged the British tank which saw one off. The crew of the second A7V abandoned their tank and fled.

The Cambrai experience undoubtedly saved many lives, influencing the British attack of 8 August1918, the battle of Amiens, in which 456 tanks finally broke the enemy lines. It was the decisive battle of the war, leading to the German surrender. The battle was launched along a thirteen-mile front. The three objectives were the Green Line, three miles from the start line; the Red Line, six miles from the start and in the center of the front; and the Blue Line, eight miles from the start and in the center. The attack was to begin at 4:20 a.m. with the tanks moving out 1,000 yards to the start line. A thick mist helped the British forces to achieve complete surprise and overrun the German forward defenses.

The main attacks were to be delivered by the Canadian Corps on the right and the Australian Corps on the left, both of them being south of the Somme. The Third Corps was to make a limited advance while covering the left flank. Before the Canadian Fifth Tank Battalion reached and crossed the Green Line objective, it had suffered heavily, losing fifteen tanks. It lost another eleven tanks achieving the Red Line, leaving it only eight machines still operable. The Canadian Fourth Tank Battalion was advancing across firm ground and achieved the Green and Red Lines with ease. Heavy German artillery then took a great toll of the Fourth’s tanks, leaving only eleven for the push on toward the Blue Line.

The Australian Corps, attacking with vehicles of the Fifth Tank Brigade, reached the Green Line by 7 a.m., the Red Line by 10 a.m. and they took the Blue Line an hour later. The tanks had eliminated German opposition up to the Red Line. After that, the Australian infantry poured through the weakened enemy defenses and the tanks were unable to keep pace with them.

After the fighting, most tank crews were suffering the ill effects from having spent upwards of three hours buttoned-up for action. With their guns firing, most of them suffered from headaches, high temperatures and even heart disturbances.

Though it was not immediately apparent, the Allies had won a great victory at Amiens, taking 22,000 German prisoners, and the German High Command realized that it had no more hope of winning the war.

In the Reichstag, the German politicians heard from their military commanders that it was, above all, the tanks that had brought an end to their resistance against the Allies. That evening the downcast Kaiser said to one of his military commanders: “It is very strange that our men cannot get used to tanks.” Major (now General) J.F.C. Fuller summed up the result: “The battle of Amiens was the strategic end of the war, a second Waterloo; the rest was minor tactics.”