On the Franco-Burgundian frontier, Calais was both a listening post for spies and a halfway house to the courts of the King of France and the Duke of Burgundy. A network of secret agents operated from the port, paid by the indefatigable Lord Hastings. In January 1473 he led yet another embassy to Duke Charles the Bold, who received them at Ghent. The English hoped to persuade him to help them reconquer France, but for the time being little progress was made. The negotiations were to be reopened by Dr Morton.

In March 1472 John Morton had been made Master of the Rolls, the third most important member of the judicature, second only to the Lord Chancellor in the Court of Chancery. He also became a privy counsellor, which in the fifteenth century was not the empty dignity it is today. Normally the royal council met in the Star Chamber at Westminster Palace, its function being not unlike that of a modern cabinet. (It must not be confused with the Great Council, to which every important personality in the realm, including all peers, was summoned.) The King’s ‘secret council’ was the institution which, under King Edward, really governed the country. Here in the Star Chamber, as one of the most powerful men in England, Dr Morton would often have met and worked with Lord Hastings.

He was closely involved in Edward IV’s foreign policy. The King hoped to revive the Hundred Years’ War and recover the lost lands across the Channel. Not only did he call himself King of France, but he had been born in Rouen when it was an English city. He was only too well aware that one of the reasons for the ruin of the House of Lancaster had been losing Normandy and Bordeaux. But a war of reconquest was only possible in alliance with Burgundy and with sufficient funds to pay an army.

Before a firm Anglo-Burgundian pact against France came into being, an extraordinarily complex series of negotiations took place between England, France and Burgundy, with truces and counter-truces. Dr Morton played a crucial role in this diplomatic offensive. He and Lord Duras spent January to June 1474 negotiating with the Duke, finally returning with a treaty of alliance in which Charles agreed that Edward should be crowned King of France at Rheims. In December, together with Sir Thomas Montgomery and William Hatclyf (the King’s physician), he went on a further embassy, dancing attendance on the Duke, who was besieging Neuss in the course of his war with the Swiss. The negotiations were not only about an offensive against France; a staple in Burgundy for Newcastle wool was proposed and there were also discussions about the Anglo-Burgundian exchange rate. They also tried, and failed, to secure a treaty with the Emperor Frederick III against France.

We catch glimpses of the little doctor in the Paston Letters; on 5 February 1475 Sir John Paston ends a missive from Calais with: ‘As for tidings here, my masters th’ambassadors Sir T Montgomery and the Master of the Rolls come straight from the duke [of Burgundy] at his siege of Neuss, which will not yet be won.’ By now, ‘Our well beloved clerk Mr John Morton, Keeper of our Rolls in Chancery’, was once again very much of a figure in English public life.

Raising money to pay for the war was far harder. Early in 1475 Paliament heard how some collectors were not levying taxes properly or else were pocketing them. The King therefore resorted to ‘benevolences’. As many rich men as possible were summoned to audiences, each one being interviewed personally by Edward. A Milanese observer noted with amusement that he welcomed every victim as if he had known him all his life, and then asked just how much he was prepared to pay towards the French war. A notary stood by to write down the amount. However much the wretched man might offer, the King would then mention that someone far poorer had given a great deal more. Few dared resist his scowl. He also kissed the victims’ wives. Edward went on progress through all England on a fund-raising tour of this sort, besides enlisting the help of mayors and sheriffs.

A glib royal spokesman told the House of Commons that war with France would reduce crime by shipping unruly elements abroad. He gave a fascinating glimpse not only of the impact of the Wars of the Roses on his hearers – ‘every man of this land that is of reasonable age hath known what trouble this realm hath suffered . . . none hath escaped’ – but on the country as a whole. Despite King Edward’s happy victory, ‘yet is there many a great sore, many a perilous wound left unhealed, the multitude of riotous people which have at all times kindled the fire of this great division is so spread over all and every coast of this realm, committing extortions, oppressions, robberies and other great mischiefs’. What he tactfully omitted from his speech was the fact that some of the great mischiefs were due to the King’s failure to control his magnates’ affinities.

Margaret Paston gave vent to a taxpayer’s exasperation in a letter to her son Sir John – ‘the king goeth so near us in this country, both to poor and rich, that I wot not how we shall live but if the world amend,’ she writes. She claims that the benevolences have impoverished all East Anglia.

An English invasion force of 11,500 men assembled in June 1475, much larger than any army commanded by Henry V. Yet though it included twenty-five peers, their troops were not of the highest quality. There were too many archers (even if a large number were mounted) and too few men-at-arms – where the ratio should have been one man-at-arms to every three bowmen, it was one to every seven. The ratio was still worse in Lord Hastings’ contingent, though he brought forty men-at-arms and 300 archers, more than any other peer save the Duke of Clarence and the Earl of Northumberland. He was supported by John Donne and two other knights with 104 archers. Very few of these troops had had experience of warfare overseas. However, there was an impressive artillery train, said to be larger than the Duke of Burgundy’s, while the King had brought a wagon-train of food in case the French should adopt scorched-earth tactics.

The army began embarking in June. As Captain of Calais, Hastings – assisted by his lieutenant, Lord Howard – was responsible for problems of billeting, besides having to liaise with the Burgundians. King Edward crossed from Dover on 4 July, Dr Morton accompanying him. They found a good deal to dishearten them. The weather was atrocious, with heavy rain, and already it was almost too late in the year to begin a campaign. Moreover, a commander as experienced as Edward realized that his troops were not entirely satisfactory.

Commynes, who watched them, comments, ‘I don’t exaggerate when I say that Edward’s men seemed very inexperienced and unused to active service, since they rode in such ragged order.’ No doubt at home they were accustomed to dismounting and fighting on foot rather than on horseback. Even so, however fiercely they may have fought each other, the armies of late-fifteenth-century England were always amateurish and unprofessional. They must have been very difficult to command, not least the haughty, quarrelsome gentlemen who officered them.

Their leader had by now grown a little too fond of his comforts, while he was scarcely encouraged by the Duke of Burgundy’s arrival at Calais without an army – the Burgundian troops were busy campaigning elsewhere.

Nevertheless, King Louis was terrified out of his wits, as though Henry V had risen from the grave. If possible, he was determined to buy off the English. He had sent flattering letters to Lord Hastings at Calais, together with what Commynes calls ‘a very big and handsome present’ (presumably money), though in reply he had received only a polite letter of acknowledgement. But soon it became obvious that the campaign was not going very well for the English – at St Quentin their advance guard was routed by cannon-fire from the town walls, some men being killed or taken prisoner. Louis sent a message into Edward’s camp. If the King of England wanted peace, then he would do his best to satisfy him. He apologized for having helped the Earl of Warwick, and emphasized how bad the weather was for July ‘when winter was already approaching’.

King Edward held a council, attended by both Lord Hastings and Dr Morton. It decided to offer Louis terms; basically these would amount to an indemnity. On 13 August Lord Howard, Thomas St Leger, William Dudley and John Morton went to negotiate with the French at a village near Amiens – a few days later they saw Louis himself.

The terms were agreed. In return for leaving France, Edward was to receive a down payment of 75,000 crowns, together with a pension of 50,000 crowns to be paid yearly. In addition, the Dauphin was to marry one of the English King’s daughters and there would be advantageous commercial clauses.

However, an agreement had not yet been signed, and Louis was anxious that the English should not change their minds. To make the settlement popular with everyone, he invited the entire English army to be his guests in the city of Amiens. If Philippe de Commynes is to be believed, what followed was the funniest episode in the whole history of Anglo–French relations.

The French King ordered two long tables to be placed on each side of the street that led into the city from its main gate. These were laden with all sorts of good dishes to accompany the wine, of which there was a very great deal and the best that France could produce. ‘At both tables the king had sat five or six boon companions, fat and sleek noblemen, to welcome any Englishman who felt like having a cheerful glass . . . nine or ten taverns were generously supplied with anything they wanted, where they could have whatever they ordered without paying for it, by command of the king of France who paid the entire cost of the entertainment which went on for three or four days.’ At one tavern that Commynes entered, 111 bills had already been run up, though it was not yet nine o’clock in the morning. The house was crowded with Englishmen, ‘some of whom were singing, others asleep and all of them very drunk’. King Edward was ashamed of his troops’ behaviour, and had large numbers of them thrown out of the city.

Louis XI had thought of everything. He even seems to have provided whores, who took their own special revenge on the invaders. ‘Many a man was lost that fell to the lust of women, who were burnt by them; and their members rotted away and they died,’ claims one doleful English chronicler.

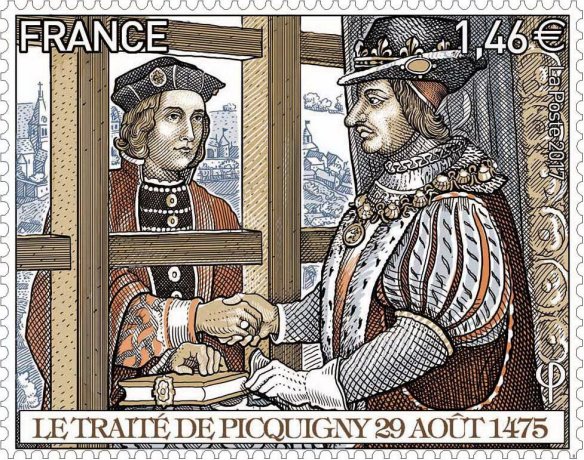

The two kings met on a bridge at Picquigny on 29 August 1475. Among those who accompanied Edward was William Hastings. ‘The king of England wore a black velvet cap on his head, decorated with a large fleur-de-lys of precious stones,’ Commynes recalls. ‘He was a prince of noble and majestic appearance but somewhat running to fat.’ Commynes adds that Edward did not look so handsome as when he had last seen him, during his flight from Warwick in 1471, but that he spoke to Louis in good French.

They had no hesitation in signing the treaty. To make certain that Edward’s councellors would support it, Louis bribed them. Hastings got most, an annual pension of 2,000 gold crowns – to be supplemented over the next two years by 24,000 more in money and plate, including two dozen silver gilt bowls worth over £600. The French King was fully aware of the power and influence of the chamberlain, whom Commynes summed up as ‘a man of sound sense, courage and authority’.

Commynes says it was not easy to persuade Hastings to accept the pension, as a loyal friend of the Burgundians who were already paying him a thousand crowns a year. King Louis sent an agent, Pierre Clairet, to England with the pensions and orders to obtain receipts so that the King could prove that Hastings and all the others were being paid by him. However, ‘at a private conversation alone with the chamberlain in his room in London’, William refused to sign for the money.

‘I didn’t ask for it,’ he told Clairet. ‘If you wish me to take it, then you can slip it in my pocket, but you’re never going to get a letter of thanks or a receipt out of me. I don’t want everybody saying “The lord chamberlain of England is in the king of France’s pay.” ’

Commynes adds that Louis was so impressed by Lord Hastings’ shrewdness that he went on paying the pension without asking for receipts, and felt more respect for him than for all the rest of Edward’s counsellors put together.

Dr Morton was also recognized by King Louis as a man of power and influence. He received a pension of 600 crowns, though we do not know if he signed receipts for it.

Some people in England grumbled at the Treaty of Picquigny. After being told for three years that they were in honour bound to pay for waging war on ‘our ancient enemies of France’, besides suffering from ‘benevolences’, their king had returned ingloriously without conquering a foot of French soil; all the bright hopes of recovering Normandy and Bordeaux had vanished into thin air. Yet for Edward IV the settlement was a triumph of realism. He had seen that his brother-in-law of Burgundy could not be relied on, while he recognized that he himself was in no condition to undertake those exhausting campaigns of conquest that had destroyed Henry V’s health. France was no longer the divided land of fifty years ago but ruled by one of her greatest kings. Instead of fighting a risky and ruinously expensive war, Edward had come home with a new source of income.

The King took the opportunity to attend to minor nuisances. Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter, did not come home. After the Lancastrian defeat at Barnet, Exeter had spent some time in sanctuary at Westminster Abbey before being moved to the Tower, where he had stayed until he either volunteered or was ordered to join the expedition. His wife Anne, King Edward’s sister, had secured an annulment so that she could marry her lover, Sir Thomas St Leger – one of her brother’s squires of the Body – with whom she was living on the Duke’s former revenues. There was no place for the haughty Exeter in a Yorkist world. On the return voyage he drowned between Calais and Dover, ‘but how he drowned, the certainty is not known’, says Fabyan. However, Giovanni Pannicharola, the Milanese envoy to the Burgundian court, was told by Duke Charles that the King of England had given specific orders for the sailors to throw his former brother-in-law overboard. It would not be the last of King Edward’s convenient drownings.

According to the same Milanese source, Duke Charles was so enraged when he heard the news of Picquigny that he ate his Garter, or at least tore it with his teeth. He had every reason to be angry, even though his lack of co-operation was partly responsible for the treaty. It weakened Burgundy enormously against France, in both military and diplomatic terms. There was no more hope of armed assistance on a really large scale from across the sea. Indeed, although English sovereigns might continue to call themselves ‘Kings of France’ until the nineteenth century, it was the end of the Hundred Years’ War. Louis had won a great, bloodless victory. He boasted to Commynes: ‘I kicked the English out of France much more easily than my father did – he had to do it by force of arms but I used venison pies and good wine.’