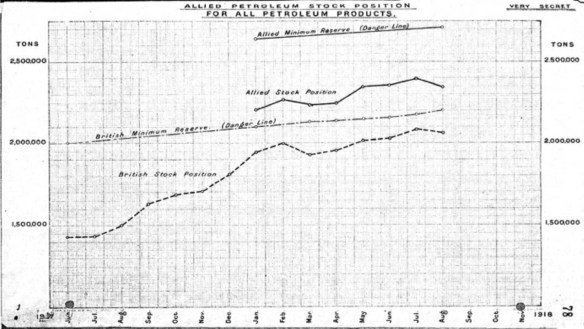

Allied Petroleum stock position for all petroleum products, August 1918

During the second phase of the Middle East in the Great War, from the beginning of 1916 to March 1917, the British and the Russians again launched offensives in Mesopotamia and Persia, and for a second time drove out the Turks, as they had done in April 1915. In February 1916, the War Office replaced the India Office in command of the Mesopotamian enterprise. With the advent of the May 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, the Middle East was partitioned into British, French, and Russian (and later Italian) spheres of influence. This agreement was based upon the recommendations of the earlier de Bunsen Committee of June 1915, which was established to formally study and forward tangible British war aims in the Middle East following the misaligned Constantinople Agreement of March 1915. “Unquestioned control” of oil resources, including related industry and transportation mechanisms, was one of six key interests promoted in its first detailed report. Emphasis was given to Mesopotamia and a future pipeline to the terminus refinery/port at Haifa, in what became the British mandate in Palestine (now Israel) following the war – a British calculation for the 1917 Balfour Declaration. Britain extended her control over the rest of the southern and eastern regions and eventually occupied Baghdad in March 1917. To Curzon, “The capture of the city would ring through the East and would cause such an impression that it would partially discount any failure at the Dardanelles.” The triumph of Baghdad and the final sanction of the principles of the ongoing McMahon-Hussein negotiations were a way of buttressing flagging British prestige in the Middle East following the evacuation of Gallipoli. During the discussions of 1915, the sharif had no intentions of actually rebelling against the Turks until the British position in the Middle East became favourable; the British had merely bought his neutrality for the time being. By 1917, however, British headway in both Mesopotamia and Palestine swayed him to fulfil his prior assurances to provide military support against the Turks. However, the capture of Baghdad, allied to the unfolding unrest in Russia, had unforeseen strategic consequences for the British.

At this time, the war began to exact a toll on civilian populations. In late 1916, widespread famine began to devastate the local populations of Persia, eastern Anatolia, and the southern Caucasus. Local crops withered, and the import of foodstuffs from India, Mesopotamia, and the United States became non-existent, because the few and bucolic local roads and railways were used for war supplies by both sides. In addition, all belligerents, whether Ottoman, British, or Russian, refused to pay for local oil, which greatly aggravated the conditions brought on by the drought and famine. Between 1917 and 1919, it is estimated that nearly half (nine to eleven million people) of the Persian population died of starvation or disease brought on by malnutrition. Those men fit enough to fight, generally took up resistance against the British, who now controlled most of the region. In addition, plagues of locusts on a biblical scale ravaged 75 to 90 per cent of crops in Syria and Lebanon throughout 1915 and 1916, leading to drought and famine, which claimed 350,000 to 500,000 lives in the region by war’s end.

The third phase of the Middle Eastern theatre of war falls in the period of April 1917 to January 1918. The Russian Revolution unfolded, causing the Russian armies in Persia and the Caucasus to disband and evacuate their positions. The agreements of 1907 and 1916 between the Allies and Russia became moot. The United States officially joined the Allied war effort in April. With the potential for more manpower on the Western Front, thanks largely to the United States, Britain afforded more troops to General Sir Archibald Murray’s Egyptian Expeditionary Force. Maude’s successes in Mesopotamia, including the capture of Baghdad in March 1917, drastically changed the situation in the Middle East. If given appropriate troop allocations, Britain could now gain ground in Persia and Mesopotamia. However, in Palestine, Murray delayed any further attacks and subverted the British War Office with spurious reports of his progress. He was replaced by General Sir Edmund Allenby in June 1917. Allenby, as mentioned, proceeded to launch successful attacks on Gaza in November 1917 and on Jerusalem in December of the same year. With these regions safely under British control, the main railway lines from the Mediterranean ports across Syria, through Arabia to the Persian Gulf were in British hands. Also ports on the Mediterranean, Red, and Caspian Seas, the Persian Gulf, and the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers were open for Allied shipping.

Flushed by these recent victories, on 2 November 1917 the British issued the Balfour Declaration demarcating a Jewish homeland in soon-to-be-conquered Palestine. This was a strategic initiative to protect British interests and to help harden American favour. Having a cordial Jewish state in Palestine would ensure British control of the Suez Canal – the pathway to the Middle East, Central Asia, and India – while protecting oil interests and providing ideal locations for the terminus of pipelines at refineries constructed at Mediterranean ports. It would also appeal to the large Jewish diaspora in the United States, who were becoming a swelling electoral bloc in U.S. cities, principally in the highly populated east. Between 1900 and 1914, as Jewish pogroms engulfed Eastern Europe and Russia, 1.5 million Jews immigrated to America. When America entered the war in April 1917, its Jewish population had risen to over 2.2 million. Today, the United States and Israel are home to 80 per cent of the world’s Jews: “The origins of modern Israel – and of the modern Palestinian national movement – date to the years immediately following Balfour’s Declaration.”

In addition, irregular Arab guerrillas, led by T.E. Lawrence, who took command of these forces in 1916, were wreaking havoc on German and Turkish reinforcements and supply depots in Palestine and Western Arabia, distracting sizeable enemy forces from the main fronts. In early 1918, however, the decaying situation in the Middle East, which was spawned by the collapse of the tsarist regime, became even more threatening to local Allied strategy. With the signing of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, Russian forces under General Nikolai Yudenich who had been embattled with both German and Turkish forces in the southern Caucasus since 1915, disintegrated. Until the summer of 1917, the Russian line extended from south Russia, through the Caucasus, across the Caspian Sea, through northwest Persia, until its left flank joined General Maude’s British forces in Mesopotamia, east of Baghdad. By October 1917, this continuous Allied line was melting away. Russian troops were deserting en masse, and the entire Russian Army announced its intention to withdraw from the area completely. With the advent of the Russian Revolution and the final collapse of the southern Russian forces in November 1917, and the unexpected death of General Maude from cholera that same month, the British faced an entirely new strategic situation.

The Turkish Army, inadvertently acting as a vanguard for German follow-on forces, found nothing between itself and the long-coveted possession of the oil-rich region of the southern Caucasus and began to work their way along the Transcaucasian Railway. A gap, some 450 miles wide, was forming on the right flank of the British Mesopotamian Force, through which Turkish and German agents and troops could encircle the Allied forces and pour into Central Asia. Germany was arming tribes in Persia, who were hostile to the British, and by the beginning of 1918, 300,000 rifles had been distributed: “With no Russian Caucasian army left to oppose them, the Turks had reversed three years of Russian gains in less than two months, restoring the 1914 borders (and going slightly past them) while hardly breaking a sweat.” The British were cognizant that these deployments were “to ensure for the Ottoman Government – 1. A powerful military position in the world. 2. Full opportunity to crush and massacre small subject races. 3. Pan-Islamic and pan-Turanian expansion in Central Asia, India and Africa. 4. Facilities for promoting dissention among the Powers.”56 The first comprehensive report detailing pan-Turanian ideology and its religious, geographical, racial, military, and strategic appendages was promulgated on 29 November 1917. The report also contained a section entitled “German Support of Pan-Turanianism,” which detailed the financial, propaganda, and clandestine efforts of German agents in the region to bolster German influence and sway under the guise of pan-Turanian backing.

Clearly the British were concerned with any push by the Turks or Germans, individually or collectively, into the Caucasus or Central Asia, “in so far as they are given opportunities by the course of events in Russia,” thereby fashioning an environment “intensely prejudicial to the position of Great Britain in India.” The newly appointed commander of the MEF, Lieutenant-General William Marshall (who replaced the deceased Maude), did not have sufficient forces to repel the inevitable onslaught. Alterations were desperately needed to safeguard British interests and operational intentions in the Middle East and the Caucasus.

The situation in the southern Caucasus and in neighbouring northwest Persia – east of the Turkish border – was extremely important to the Allies, specifically the British. Throughout the war, India was threatened from the Northwest Frontier, aggravated by the hostility of a considerable portion of the Afghan population, lured by German agents and bribes. As part of the kaiser’s plan to ignite jihad in India against the British Raj, a secret emissary was sent to Afghanistan to convince Emir Habibullah to instigate a holy war in India. This 1915–16 mission operated at the “vortex of four clashing empires – the German, Ottoman, Russian, and British.” Led by diplomat Werner-Otto von Hentig, the mission “wound its way from Berlin to Vienna to Constantinople to Baghdad … to Herat and Kabul.”

In central Persia, Hentig was joined by the resourceful and wily Oskar Niedermayer, often referred to as the “German Lawrence.” This picaresque enterprise, however, was plagued by complications from the outset, and as early as November 1914, British spies had full knowledge of the German-Afghan initiative. More importantly, in March 1915, British agents seized a diplomatic codebook in western Persia abandoned by Wilhelm Wassmuss, an elusive German agent, allowing them to intercept messages from German consuls in the Ottoman Empire and also those sent by Hentig and Niedermayer. The greatest difficulty for these German emissaries, however, was to convince the emir to abandon his bonds with the British, which had been validated through a 1905 Treaty of Friendship.

Knowing German intentions, the British began to flood Kabul with propaganda and sent the emir personal messages regarding the progress of the German party, spotted with disinformation. King George V wrote a personal letter to his Afghan peer on 24 September 1915, “My Dear Friend, I have been much gratified to learn … how scrupulously and honourably Your Majesty has maintained the attitude of strict neutrality which you guaranteed at the beginning of the war, not only because it is in accordance with Your Majesty’s engagements to me, but also because by it you are serving the best interests of Afghanistan and the Islamic religion [and] still further strengthen the friendship which I so greatly value, which has united our people since the days of your father, of illustrious memory, and of my revered forebear, the great Queen Victoria.” In an accompanying letter from Charles Hardinge, the viceroy of India, the emir was informed that his annual subsidy would be increased by £25,000 (from £400,000 to £425,000). In reality, Habibullah still had £800,000 of unspent credit in Delhi, in addition to sizeable investments in London.

In the meantime, Niedermayer and his motley crew of twenty-five “dried up skeletons” evaded British and Russian pursuers, and after seven perilous weeks in the Persian desert (marching some 30–40 miles per day in temperatures upwards of 50°C), crossed the Afghan frontier on 19 August 1915. Kabul, although in sight, still lay some four hundred miles east, with the gates to India only two hundred miles beyond. On 2 October, one year after Niedermayer had left Constantinople, the Germans entered the Afghan capital. Habibullah, however, was intelligent, cautious, and a savvy veteran of Great Game politics. Having just received the entreaty from King George and a raise in pay, he was in no hurry to hold audience with the German envoys, who spent the next twenty-four days in cordial, albeit guarded, house arrest: “Habibullah’s caution was wholly in character. He had not survived as sovereign of his realm for fourteen years in between the British and Russian empires without learning how to play the powers off against one another. Far from the provincial tribal Islamic headman the Germans had imagined him to be, the Emir was European in both his dress and his manners, and evidently well informed about the world war.” The emir was obviously well aware of his opportunity to play the game with a new set of pawns: Britain and Germany.

At last on 26 October, Habibullah’s Rolls-Royce (the only car in Afghanistan) collected Hentig and Niedermayer and shuttled them down the paved road (again the only one in Afghanistan) to his palace. Over the course of the next two months, the emir held daily meetings with his guests, listening to their propositions. He maintained his poker face, however, refusing to play his hand by rarely saying a word in response. Although his manners were beyond reproach, Habibullah treated the Germans as if “we were businessmen with various goods [to sell], from which he wished to determine which would be good or useful to him.” The emir was receiving intelligence from the British, who were generally pleased with his policy of “masterly inactivity.”

Finally, on 24 January 1916, Habibullah signed a treaty with the Germans; the crowning moment of his brilliant self-serving scheme. To replace his British subsidies, which would be forfeit if his forces invaded India, he secured a sum of £10 million (£5 billion today), in addition to the promise of 100,000 modern rifles, 300 artillery pieces, and other contemporary military equipment. Lastly, he assured Hentig and Niedermayer that the invasion would begin when a force of 20,000 well-armed Turkish and German soldiers arrived to cover the rear against an inevitable Russian attack – which both parties knew was logistically impossible. Niedermayer was rightly “convinced that any attempt to induce Afghanistan to go to war against India is futile as long as it is based only on diplomatic activities.” The following day, Habibullah summoned the British agent and declared his continued loyalty and neutrality and belatedly replied to King George reaffirming this position. By playing both nations, Habibullah ensured that he would be on the winning side, regardless of who actually won the war. The treaty with the Germans was merely an insurance policy, for if the untenable terms, calculatingly imposed by the emir, were ever met, the Central Powers would have to be categorically winning the war.

Habibullah continued to delay until the Germans had finally given up hope of cooperation and of an Afghan invasion of India. With the sweeping 1916 Russian gains in Anatolia and Persia, the Arab revolt in Mesopotamia, and the failure of the German offensive at Verdun on the Western Front, both Germany and the Ottomans had more immediate concerns. On 15 February 1916, the Russians seized the impregnable fortress of Erzurum, sending the Turkish Third Army into a hasty retreat towards Ankara: “It was a bitter blow to Turco-German prestige. Any chance Niedermayer still had of inducing Emir Habibullah to launch an Afghani holy war against British India most likely perished in the snows of Erzurum.” As a result, Niedermayer and Hentig left Kabul towards the end of May 1916, and with them the kaiser’s hopes of igniting rebellion in India via Afghanistan.

Hentig escaped east with stops in Shanghai, Honolulu, San Francisco, Halifax (Canada), and Bergen (Norway) before reaching Berlin. Niedermayer also eventually made it back to Tehran, having been beaten, robbed, and left for dead in the Persian desert by his Turkish escorts. He reported to the German Embassy, “Our next and most important objectives are the Caucasus and northern Persia.” He would reappear in Mesopotamia in early 1917, coming face-to-face with his British counterpart, Lawrence of Arabia, as part of the German-reinforced Turkish Yildirim Army (Lightning Army) or Heeresgruppe F, initially commanded by General Erich von Falkenhayn and later by General Liman von Sanders. This unit attempted without success to crush the Arab revolt and deny British advances in Palestine and Mesopotamia. Nevertheless, during 1915–16, the danger posed by their mission to Afghanistan was viewed as a great threat in British circles. According to Brigadier-General Sir Percy Sykes, commander of the South Persian Rifles, “The German Mission to the Emir created a crisis of the first magnitude in Afghanistan and was a source of the gravest anxiety in India.” Any advance on India by Turkey would influence the fortunes of not only India, but the entire British Empire. India was the source of considerable wealth in raw war materials vital to the Allied war effort.

To avoid such a catastrophy, the strategic solution was to limit Turkey’s access to the transportation routes leading south to India, the majority of which were in the Middle East. The main cities on both the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, including Mosul, Baghdad, Fallujah, and Basra, and the northern Caspian ports of Enzeli and Baku, were vital ground in halting any southeast Turkish or German advance. The British also needed to protect the road from Baghdad to the port of Enzeli. The road, 630 miles long, climbed through a succession of mountain ranges and desolate regions and was frequently raided by Turkish or hostile Persian forces being encouraged by German/Turkish agents. In addition, hostile Jangali tribesmen under Kuchik Khan controlled all approaches to Enzeli. The protection of this route was under Marshall’s mandate, but he could not devote any resources to its security, given his obligations in Mesopotamia and his already overextended forces.

With the Russian departure and Marshall’s MEF and Allenby’s EEF lacking the capacity to expand operations beyond their current area of operations, it was necessary to insert secondary forces to meet strategic objectives in the Middle East. The Russian force that had long held the Caucasus-Persian front fluctuated between 125,000 and 225,000 soldiers. The Allies could not spare reinforcements from any theatre, including those in Palestine or Mesopotamia, to replace these numbers. Highly mobile and highly trained special forces seemed to be the only alternative. As mentioned, there were a number of other relatively obscure Allied “sideshow” campaigns within volatile, post-revolution Russia.70 The necessity for Allied intervention into both northern and southern Russia was a reaction to the overall strategic situation, which had been significantly transformed during 1917. Within this paradigm Dunsterforce was deployed to northern Persia and the Caucasus in 1918 to safeguard British oil interests.