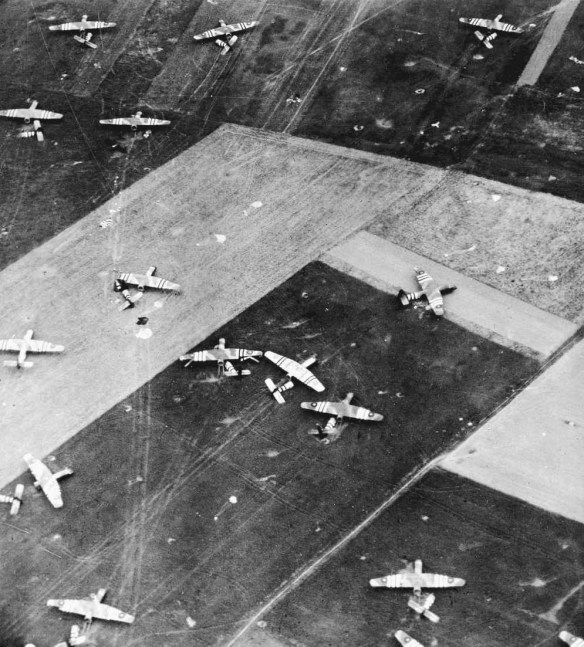

Oblique aerial view of parachutes and Airspeed Horsa gliders on Landing Zone N of the British 6th Airborne Division near Ranville, France, on the morning of June 6, 1944. (Royal Air Force Official Photographer/IWM via Getty Images)

A glider is an aircraft without an engine that is most often released into flight from an aerial tow aircraft. During World War II, both the Axis and Allied militaries developed gliders to transport troops, supplies, and equipment into battle. Although this technique had been discussed prior to the war, it had not been implemented. Gliders were to land behind enemy lines, often at night, and the men carried by them would then become infantrymen once on the ground.

The Germans were first to recognize the potential of gliders in the war, in large part because of extensive pre–World War II scientific research and sporting use. The Germans embraced gliding because it did not violate military prohibitions in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. Gliding clubs, which developed in other countries as well, increased interest in the sport worldwide. Sport gliders used air currents to climb and soar for extended periods, while military gliders simply descended on release from aerial tows.

The Germans employed gliders in their invasion of Belgium and the Netherlands in May 1940, especially in securing Fort Eben Emael (May 10), the key to overrunning Belgium. The Germans also used gliders in the invasion of Crete (May 21–June 1, 1941) and during fighting in the Soviet Union in the Battle of Stalingrad (August 23, 1942–February 2, 1943).

Great Britain was the first Allied nation to deploy gliders. The Air Ministry’s Glider Committee encouraged the use of the Hotspur to transport soldiers in late 1940. The Hotspur had a wingspan of 61 feet 11 inches, a length of 39 feet 4 inches, and a height of 10 feet 10 inches. It weighed 1,661 pounds empty and 3,598 pounds fully loaded. The Hotspur was designed to transport two crewmen and six soldiers. A total of 1,015 were built.

In 1941, the British developed the Airspeed A.S. 51 Horsa. It had a wingspan of 88 feet, a length of 68 feet, and a height of 20 feet 3 inches. It weighed 8,370 pounds empty and 15,750 pounds fully loaded. It had a crew of two men and was capable of carrying 25 passengers or two trucks. In all, some 5,000 Horsas were built. They were employed in Operation OVERLORD east of the British invasion beaches, most noteworthy in the successful effort to seize control of Bénouville Bridge (Pegasus Bridge) spanning the Caen Canbal.

The largest Allied glider was the British General Aircraft Limited GAL 49 Hamilcar. With a wingspan of 110 feet, a length of 68 feet 6 inches, and a height of 20 feet 3 inches, it weighed 18,000 pounds empty and 36,000 pounds fully loaded. It had a crew of 2 and could transport 40 troops, a light tank, or artillery pieces. A total of 412 were built.

By the time of the Normandy invasion, only 50 Hamilcars had been produced. Thirty-four were employed as part of Operation MALLARD in support of the British 6th Airborne Division. They transported Tetrarch light tanks and antitank 17-pounder guns. Several gliders were damaged on landing and their cargo lost.

The U.S. Navy explored the possibility of military applications for gliders as early as the 1930s. In February 1941, chief of the Army Air Corps Major General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold ordered specifications drawn up for military gliders. The Waco Aircraft Company in Troy, Ohio, received the first U.S. government contract to build training gliders, and the army began organizing a glider training program.

Constructed of plywood and canvas with a skeleton of steel tubing, the Waco CG-4A had a wingspan of 83 feet 6 inches, a length of 48 feet 4 inches, and a height of 12 feet 7 inches. Its empty weight was 3,300 pounds, and its loaded weight was 7,500 pounds. It had a crew of 2 men and could carry 13 troops or 3,800 pounds of cargo, including artillery pieces, a bulldozer, or a jeep. The Ford Motor Company plant at Kingsford, Michigan, manufactured most of the U.S. gliders, although 15 other companies also produced the Waco. In all 13,908 Wacos were built, making it the most heavily produced glider of the entire war by any power.

Towed by the Douglas C-47 transport, the Waco was first employed in the July 1943 Allied invasion of Sicily. A number of Waco gliders were used in Operation OVERLORD to land men and equipment east of the invasion beaches. A number were damaged or lost, and there were heavy casualties.

Because the gliders were so fragile, soldiers dubbed them “canvas coffins.” Men and cargo were loaded through the wide, hinged nose section, which could be quickly opened. Moving at an airspeed of 110–150 miles per hour at an altitude of several thousand feet, C-47s towed the gliders with a 300-foot rope toward a designated landing zone and then descended to release the glider several hundred feet above the ground.

En route to the release point, the glidermen and plane crew communicated with each other either by a telephone wire secured around the towline or via two-way radios. Glider duty was quite hazardous; sometimes the gliders were released prematurely and did not reach the landing zones, and on occasion gliders collided as they approached their destination.

The U.S. 11th, 13th, 17th, 82nd, and 101st Airborne Divisions were organized with two glider infantry regiments, a glider artillery battalion, and glider support units. U.S. gliders were sent to North Africa in 1942 and participated in the July 9–August 22, 1943, Sicily invasion, accompanied by British gliders. High casualties sustained in that operation led General Dwight D. Eisenhower to question the organization of airborne divisions and to threaten to disband glider units. A review board of officers convinced the military authorities to retain them, however. Improvements were also made in structural reinforcement of the glider and in personnel training.

By mid-1944, gliders had become essential elements of Allied invasion forces. Occasionally they were used to transport wounded to hospitals. During the Normandy invasion, U.S. glidermen with the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions flew across the English Channel in 2,100 gliders to participate in the D-Day attack. Many gliders and crews were lost. New gliders were manufactured for Operation MARKET GARDEN, the assault on the Germans in the Netherlands, three months later.

Initially the military did not authorize hazardous-duty pay for glidermen, who also did not qualify for wing insignia worn by parachutists. Some of the men created posters; one read “Join the Glider Troops! No Jump Pay. No Flight Pay. But Never a Dull Moment.” By July 1944 glider wings were authorized for glider soldiers, and they received hazardous-duty pay. Also in 1944, the modified Waco CG-15A appeared, offering improved crash absorption. The Waco CG-18A could carry 30 soldiers and was deployed during the 1945 Rhine campaign. Gliders were gradually phased out of military inventories after the war, although the Soviet Union retained them through the 1950s.

Airborne Forces, British and American

The concept of airborne forces originated in 1918 during World War I, when Colonel William Mitchell, director of U.S. air operations in France, proposed landing part of the U.S. 1st Division behind German lines on the Western Front. Thus was born the idea of parachuting, or air-landing troops behind enemy lines to create a new flank, what would be known as vertical envelopment. The concept was put into action in the 1930s.

The U.S. Army carried out some small-scale experiments at Kelly and Brooks fields in 1928 and 1929, and in 1936 the Soviets demonstrated a full-blown parachute landing, with some 5,000 men taking part. British reaction to the reports of experiments with airborne forces in the Soviet Union was of mild interest only, although the Eastern Command staged some antiparachutist exercises. There the matter rested until the Germans showed how effective parachute and air-landing troops were when they carried out their spectacular air assaults in Norway, Denmark, and the Netherlands in 1940.

Although manpower demands in Britain in 1940 were such that it should have been impossible to raise a parachute force of any significance, at the urging of Prime Minister Winston L. S. Churchill, 500 men were undergoing training as parachutists by August 1940. Fulfillment of Churchill’s order that the number be increased to 5,000 had to await additional equipment and aircraft, however. Inevitably, such a new branch of infantry was beset with problems, mainly of supply, but there was also resistance to the concept within the regular units of the British Army. This often led battalions to post their least effective men to such new units merely to get rid of them.

The War Office, representing the British Army, and the Air Ministry, representing the Royal Air Force (RAF), had to agree on aircraft. Because the Bomber Command was becoming aggressively conservative of aircraft, the only plane initially available for training and operations was the Whitley bomber. Aircraft for the airborne forces were thus severely limited until a supply of Douglas C-47 Dakota (Skytrain, in U.S. service) aircraft was established, whereupon the parachute troops found their perfect drop aircraft. The British were also the first Allied nation to develop gliders as troop-carrying aircraft.

Progress in developing British airborne forces was slow; RAF objections were constant, in view of the pressure to carry the continental war to Germany via the strategic bombing campaign. Once the United States entered the war, however, the situation eased enormously, and equipment that Britain was unable to manufacture became readily available.

To provide more men for the airborne forces, the War Office decided in 1941 that whole battalions were to be transferred, even though extra training would be needed to bring many men up to the standards of fitness required of airborne troops. At the same time, the Central Landing Establishment became the main training center for airborne forces. The 1st Parachute Brigade, consisting of four parachute battalions, was established under Brigadier Richard N. “Windy” Gale. Initially three battalions were formed, which exist to this day in the British Army as the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Battalions, Parachute Regiment.

The Glider Pilot Regiment was also formed in 1941. Pilots were selected from army and RAF volunteers, but they were part of the army once trained. Airborne forces are infantry, but they had to be fitter than the average soldier, and training was rigorous. Troops were trained to endure in the cold, in wet weather, and in heat. They also had to be fit to withstand the impact of the landing, to fight alone with light weapons, and to fight without support for some days.

The airborne concept at that time was twofold: to raid, in which case troops would be extracted by land or sea after the operation (such as the attack on the German radar station at Bruneval in northern France on February 27–28, 1944), or to land at the rear of the enemy to capture a strategic target. Two examples of the latter are the Orne bridge landing on D-Day, June 6, 1944, and Operation MARKET GARDEN (MARKET was the airborne portion) on September 17–26, 1944, when the 1st Airborne Division tried to secure the bridges across the Rhine at Arnhem in Holland.

U.S. Army chief of staff General George C. Marshall was an enthusiastic advocate of airborne forces. The first U.S. airborne division was the 82nd, a conversion of the 82nd Infantry (all-America) Division, formed in March 1942. Major General Omar N. Bradley commanded the division, with Brigadier General Matthew B. Ridgway as his assistant. Ridgway was appointed divisional commander as a major general in June 1942, and the division became the 82nd Airborne Division that August.

The 82nd went to North Africa in April 1943, just as German resistance in that theater was ending. The division took part in operations in Sicily and Normandy and, under the command of Major General James M. Gavin, participated in Operation MARKET GARDEN in the Nijmegen-Arnhem area and also in the Ardennes Offensive (December 16, 1944–January 16, 1945).

The 101st Airborne Division was activated in August 1942 with a nucleus of officers and men from the 82nd Airborne Division. The 101st was commanded by Major General William C. Lee, one of the originators of U.S. airborne forces, and left for England in September 1943. Lee had a heart attack in the spring of 1944, and Major General Maxwell D. Taylor took over, leading the division through D-Day and Operation MARKET GARDEN, when it secured the bridge at Eindhoven. The division distinguished itself in the defense of Bastogne during the German Ardennes Offensive.

Three other U.S. airborne divisions were established: the 11th, which served in the Pacific, jumped onto Corregidor Island, and fought in the February 3–March 4, 1945, Battle of Manila; the 17th, which was rapidly moved to Europe for the German Ardennes Offensive and then jumped into the Rhine crossing with the British 6th Airborne Division; and the 13th, which, although it arrived in France in January 1945, never saw action. British airborne forces also saw limited service in the Pacific theater.

There was close cooperation between British and U.S. airborne forces. When the U.S. 101st Airborne arrived in England, it was installed in a camp close to the training area for the British 6th Airborne Division. Training and operational techniques were almost identical, and there were common exercises and shoots to create close bonds among troops. There were also frequent personnel exchanges to cement friendship. Similar arrangements were made between the U.S. 82nd Airborne and the British 1st Airborne Division.

Parachute training in the United States was centered at Fort Benning, Georgia, and in 1943 some 48,000 volunteers commenced training, with 30,000 qualifying as paratroopers. Of those rejected, some were kept for training as air-landing troops.

One great contribution made by the United States to the common good was the formation and transfer to England of the U.S. Troop Carrier Command. As noted, transport aircraft shortages bedeviled airborne forces’ training and operations from the outset. The arrival of large numbers of C-47 aircraft was a major assist. The RAF in 1944 had nine squadrons of aircraft, or a total of 180 planes, dedicated to airborne forces.

Polish troops were also trained in Britain as parachutists to form the Polish 1st Parachute Brigade, which fought at Arnhem in MARKET GARDEN. Contingents from France, Norway, Holland, and Belgium were also trained, many of whom served operationally in the Special Air Service Brigade. The British Commonwealth also raised parachute units. The 1st Australian Parachute Battalion served in the Far East, and the Canadian 1st Parachute Battalion served in Europe.

Several small-scale operations had been carried out before 1943 with mixed success, but the big date for airborne forces was June 6, 1944. Plans for D-Day required the flanks of the invasion beaches to be secured in advance, and only airborne forces could guarantee this. Available in Britain for the invasion were two British airborne divisions (the 1st and 6th) and two American airborne divisions (the 82nd and 101st). The plan was to use all the available airborne and glider-borne troops in the initial stages of the operation. Unfortunately, even in June 1944 transport aircraft available were insufficient for all troops to be dropped at once. All aircraft were organized in a common pool so that either British or American troops could be moved by mainly American aircraft. This was another fine example of the cooperation that existed at all levels within the Allied airborne forces.

Operation OVERLORD (D-Day) began for the paratroopers and gliders in the dark early on June 6. To the west, American paratroopers dropped at the base of the Cotentin Peninsula to secure the forward areas of what were to be Omaha and Utah Beaches. Despite many dispersal problems, most of the troops managed to link up and were soon in action, denying the Germans the ability to move against the beachheads. The troops fought with great gallantry despite their weakened strength (caused by air transport problems), and by the end of the day contact had been established with the invasion forces from the beachheads. In the east, Britain’s 6th Airborne Division was charged with controlling the left flank of the British invasion beaches.

Perhaps the most startling operation (for the Germans) was the coup de main attack by glider-borne air-landing troops of 11th Battalion, Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, who landed so close to their target that they were able to capture bridges over the Caen Canal and the Orne River. On a larger scale, the 3rd Parachute Brigade was ordered to take out the Merville Battery, which posed a threat to the invasion beaches. The 9th Parachute Battalion, which planned to attack with 700 men, was so spread out on landing that only 150 men were available. With virtually no support, the men attacked the battery and captured it. The battalion lost 65 men and captured 22 Germans; the remainder of the German force of 200 were either killed or wounded.

All Allied parachute and glider troops in the war were of a high standard, and their fighting record bears this out. Even when things went wrong, as often happened when troops were dropped from aircraft, the men made every effort to link up and carry out the task they had been given.

Further Reading

Devlin, Gerard M. Silent Wings: The Saga of the U.S. Army and Marine Combat Glider Pilots during World War II. New York: St. Martin’s, 1985.

Lowden, John L. Silent Wings at War: Combat Gliders in World War II. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992.

Masters, Charles J. Glidermen of Neptune: The American D-Day Glider Attack. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1995.

Mrazek, James E. Fighting Gliders of World War II. New York: St. Martin’s, 1977.

Mrazek, James E. The Glider War. New York: St. Martin’s, 1975.

Seth, Ronald. Lion with Blue Wings: The Story of the Glider Regiment, 1942–1945. London: Gollancz, 1955.

Smith, Claude. The History of the Glider Pilot Regiment. London: Leo Cooper, 1992.

Gale, Sir Richard Nelson. With the 6th Airborne Division in Normandy. London: Smason Law, Marston, 1948.

Harclerode, Peter. Para. London: Arms and Armour, 1992.

Imperial General Staff. Airborne Operations. London: War Office, 1943.

Otway, T. B. H. Official Account of Airborne Forces. London: War Office, 1951.

Rottman, Gordon. World War II Airborne Forces Tactics. Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2006.

Wright, Robert K., and John T. Greenwood. Airborne Forces at War. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2007.