The British set out to capture the Bogue forts on the Bocca Tigris River between Canton and Hong Kong. A Chinaman at Macao told a British army surgeon: ‘Same time you Englishman take that fort, same time that sky make fall down.’ But the forts were taken, the sky did not fall, and the Chinese were forced to sign, on 20 January 1841, an agreement known as the Convention of Chuenpi.

1840–54

IN the preceding century and until the end of the wars with France it had been the Royal Navy which had been the most important arm of Britain. In Queen Victoria’s reign it was the Army which played the key role in building and preserving the Empire. Still, the Royal Navy had its part to play, not only in transporting troops and supplies and sometimes providing naval brigades to fight side by side with the soldiers on land, but occasionally taking a direct active role in the growth of the Empire, as it did in Syria in 1840 when, in conjunction with Austrian and Prussian ships, it thwarted the expansionist tendencies of Mohammed Ali.

A year earlier a smaller but in the long run far more important naval operation took place in southern Arabia. In December 1836 a British ship was wrecked and plundered on the coast of Aden, then an independent sultanate. After prolonged negotiations, the sultan promised compensation, but he died and his son refused to honour the agreement. So on 19 January 1839 a military and naval force under Captain H. Smith in the 28-gun frigate Volage captured Aden, and this small but strategic piece of real estate was added to the Empire. Captain Smith then sailed off to Hong Kong where, on 4 September, he fired the shots which began the Opium War.

The cause of the Opium War has been attributed simply to the greed of the British merchants in China, but the real causes of the war were cultural rather than commercial: British opium smuggling and the vigorous attempts of the Chinese government to suppress it only sparked the war, which would have taken place sooner or later in any event.

The Chinese and the British were alike in that both regarded their own culture, civilization and way of life as infinitely superior to all others. It was only natural, then, that where the two cultures met there was friction: Chinaman and Briton were astonished at the pretensions of each other; to each, the other was a barbarian. Neither made much of an attempt to understand the other, and doubtless it seems surprising to most Englishmen even today that the Chinese regarded them as inscrutable.

The Chinese wanted foreign merchants to obey Chinese laws, submit to Chinese justice, and to conform to stringent Chinese regulations regarding their export-import business, demands that do not seem unreasonable considering that the foreigners were trading with Chinese in China. The foreign merchants, principally British and Americans, did not like Chinese laws, which they flouted; they thought Chinese notions of justice were unjust, preposterous and barbaric; and they felt unduly constrained by the, to them, peculiar restrictions put on their trading methods. But what annoyed them most was that they were treated, every day, in word and deed, as if they were the inferiors of the Chinese. And the British found this hard to bear. They complained, but they did adjust to the situation. All might have gone on peaceably enough had the Chinese government been strong enough to enforce its rules and had the British government not appeared on the scene in the shape of a series of envoys, consuls and trade commissioners, who were followed in due course by soldiers and sailors.

The war might have been called with greater propriety the Kowtow War, for, as John Quincy Adams told the Massachusetts Historical Society, opium was ‘a mere incident to the dispute, but no more the cause of the war than the throwing overboard the tea in Boston harbour was the cause of the North American revolution’. Adams correctly diagnosed the case when he said, ‘the cause of the war is the kowtow’.

When the first British official arrived in Pekin in 1792 he refused to kowtow when presented to the emperor. That is, he refused to make the prostrations, face touching the floor, which protocol required in the presence of the Son of Heaven and Emperor of China. It was an attitude much admired at home and was copied by later official British representatives. The British thought the kowtow humiliating; the Chinese regarded their refusal to perform it as inexplicable and decided that it would be better if they simply avoided seeing the ill-mannered barbarians altogether: British diplomatists were not even permitted to meet provincial governors. Consequently, British officials joined the merchants in complaining of the humiliating treatment they received at the hands of the Chinese, and, as the complaints of officials, being addressed to other officials and to politicians, always carry more weight than the cries of mere merchants, there was a good deal of irresponsible talk by responsible men about teaching the Chinese a lesson and putting them in their place.

When Lord Napier (William, 8th baron, 1786–1834) went to China as Chief Superintendent of Trade in 1833 he was not even allowed to stay in the country, except at the Portuguese colony of Macao, and he indignantly wrote home asking for ‘three or four frigates and brigs, with a few steady British troops, not Sepoys’. The ships and soldiers were not sent, but there was a growing feeling in England that something would have to be done to defend British prestige in China.

Meanwhile, the harvests continued in the poppy fields of Bengal and the opium clippers, in the season, swiftly and efficiently carried their chests to China, off-loading on the coasts, in the rivers or on islands just offshore. Often accused of being hypocritical, Victorian Britons rarely were, although they often succeeded in honestly deceiving themselves. Regarding the shipment of opium to China, however, they were indeed hypocritical. The East India Company, which then ruled most of India, refused to allow opium to be transported in their own ships, but they encouraged the trade, and for a very good reason: export taxes on opium came to provide more than 10 per cent of India’s gross revenue. As to the morality of the business, many Britons tried to justify it by saying that opium smoking in China was really no worse than gin drinking in England (although gin drinking in England had grown out of hand and at best this was a poor excuse).

At Canton, where foreigners were allowed to establish their offices and warehouses (called factories), the opium trade flourished. All the great British trading companies in China indulged in it and the local Chinese officials were easily bribed. Then, in January 1839, the Emperor sent an unbribable mandarin, Lin Tse-hsu, as Imperial High Commissioner to stamp out opium smuggling. Lin gave fair warning, then he struck.

Lin first tried to show the foreigners in little ways that he was indeed serious in his determination to stop the opium trade: in Macao and Canton some smugglers were publicly strangled in front of the British and American factories. An Imperial edict was issued flatly stating that opium smuggling must cease and that stocks now in store must be surrendered. When the foreigners refused to comply with the edict, they were shut up in their factories without Chinese servants or workers, forcing them to cook their own food and clean their own houses. It was considered a great hardship. This incident in May 1839 became known as the Siege of the Factories. It ended when the British, greatly humiliated, gave up 20,000 chests of illegally imported opium. Obviously the British could not go to war over this issue, even though dignity and prestige were involved; a larger issue was needed.

Six weeks after the Siege of the Factories, some British and American sailors started a brawl in a village near Kowloon and a Chinaman was killed. The Chinese authorities demanded that the murderer be given up; the British refused, maintaining, perhaps correctly, that it was impossible to discover exactly who had done the deed. Commissioner Lin withdrew all supplies and labourers from British homes and factories and ordered the Portuguese governor of Macao to expel all the British from his territory. Men, women and children were loaded on British ships, which sailed over to Hong Kong, then a virtually uninhabited island, and anchored. Here floated the entire British colony, a westernized version of the sampan communities commonly found in Chinese ports. It was at this juncture that Captain Smith arrived in the Volage, fresh from his successful operations against the Arabs at Aden, and he was presently joined by the 20-gun frigate Hyacinth.

Without British officials and the samples of British power on the scene all might have ended peaceably enough, for both the Chinese and the merchants wanted to trade, but now merchants, officials and sailors were delighted by the opportunity to humble the arrogant Chinese and to pay them back for the years of indignity. Chinese were found who were willing to supply the floating British community with food under the protection of the frigates. When the Chinese government sent war junks to stop the trade, Captain Smith drove them off with the fire of the Volage. The Chinese then sent a fleet of twenty-nine war junks against the two frigates, and in the battle that followed four junks were sunk and others were badly damaged at no loss to the British ships. The war had begun.

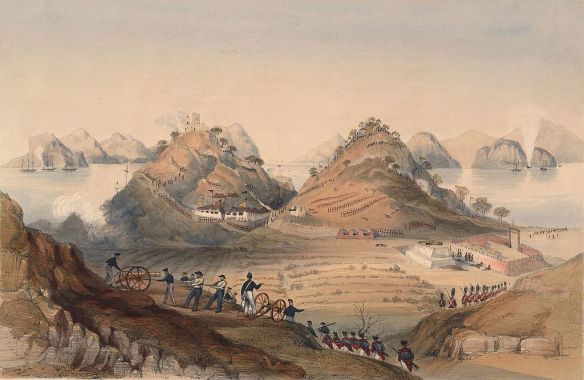

There was the usual debate in the Commons, in which the Palmerston government pointed out that not only had British property been confiscated but British officials had been insulted; Gladstone protested that ‘a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated to cover this country with permanent disgrace, I do not know and I have not read of’; still, the approval was given for the government to prosecute the war. Troops were sent out from India – the Royal Irish, the Cameronians, men from the Hertfordshire regiment, and some sepoys: 4,000 men in all – and more warships were provided. Captain the Honourable Sir George Elliot was in charge of the naval operations, joining his cousin, Charles Elliot, who was the ranking civil official in China; they were shortly to be joined by Major General Sir Hugh Gough, who took charge of the army. Their orders were to occupy Chusan, blockade Canton, deliver a letter of protest to the chief minister of the Emperor, and force the Chinese government to sign a treaty. All this was done. Chusan was occupied without a fight and British troops were left there to die in great numbers of oriental diseases; eventually a Chinese official was forced to accept the letter from England; then the British set out to capture the Bogue forts on the Bocca Tigris River between Canton and Hong Kong.

A Chinaman at Macao told a British army surgeon: ‘Same time you Englishman take that fort, same time that sky make fall down.’ But the forts were taken, the sky did not fall, and the Chinese were forced to sign, on 20 January 1841, an agreement known as the Convention of Chuenpi. In it the Chinese agreed to give Hong Kong to the British, to pay them six million dollars, to reopen trade at Canton and to deal with British officials as equals, but both the Emperor of China and Her Majesty’s government repudiated the treaty: the Emperor because his representative gave too much and Palmerston because his representative had not got enough.

The British government’s policy on China was debated in Parliament and came under attack by Gladstone, ever the champion of the noble savage, who horrified his opponents by maintaining that it was even right for the Chinese to poison wells to keep away the English. But Queen Victoria agreed with her ministers. She took such a keen interest in China that Palmerston sent her a little map of the Canton River area ‘for future reference’.

Palmerston was thoroughly disgusted with Elliot, and as for the barren little island he had acquired Palmerston told him: ‘It seems obvious that Hong Kong will not be a mart of trade.’ But the Royal Family was fascinated by the acquisition of a territory with such a quaint name as Hong Kong, and Queen Victoria wrote to Uncle Leopold to say that ‘Albert is so much amused at my having Hong Kong, and we think Victoria ought to be called Princess of Hong Kong in addition to Princess Royal’. But the Queen, reflecting Palmerston’s views, was not pleased with Charles Elliot, and in the same letter to King Leopold she expressed her displeasure: ‘The Chinese business vexes us very much and Palmerston is deeply mortified at it. All we wanted might have been got, if it had not been for the unaccountably strange conduct of Charles Elliot . . . who completely disobeyed his instructions and tried to get the lowest terms he could.’ Clearly, more war was wanted.