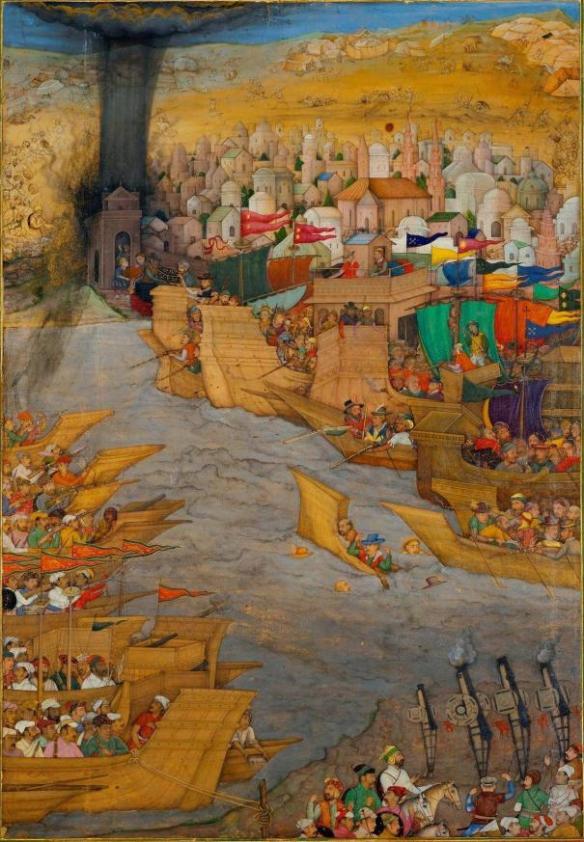

The capture of Fort Hooghly from the Portuguese by the Nawab of Bengal in 1632. 17th century Mughal Miniature Painting

Interestingly, the theatres of riverine war – the Lower Indus Basin, the Lower Ganga Basin and the Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta – saw the use of gunpowder artillery at a far greater scale than what could be deployed elsewhere, the reasons being majorly logistical. Sixteenth-century heavy artillery was extremely difficult to be carried overland and entailed an enormous cost in terms of money, manpower as well as time. The waterways were the most convenient for transporting these heavy pieces. While arguing a case for the centrality of gunpowder artillery in Mughal state formation, it can be suggested that in central India and further south, Mughal centralization was incomplete and shaky precisely due to the absence of waterways to carry the artillery in there. Even if one does not accept the central role assigned to gunpowder artillery in Mughal state formation, it is true that the Mughals found it extremely difficult to carry their heavy artillery into central India and the Deccan from Agra during this time. Consequently, the sieges in this region saw a limited use of gunpowder artillery. In these regions, the Mughals conducted siege warfare with traditional means, like blockade, mining and escalades. Compared to this, amphibious wars saw much greater deployment of artillery because they could be easily mounted on boats and then deployed at will. The position of gunpowder artillery in Mughal military history, hence, is much more complex than the historians arguing in favour of a Gunpowder Empire would suggest. The imagery of cannons blasting away one fort after another, and thereby acting as the vanguard of empire, as the case had been in France or Spain, is alien to the Indian subcontinent, even in the riverine regions which saw heavy deployment of gunpowder artillery. However, not only artillery, but all types of projectile throwing branches of the army – musketeers, rocketeers and archers – were much valued in this mode of warfare.

Command of fortified locations has always been the key to long term success in pre- modern warfare. While a victory in a pitched battle might vanquish the enemy on one day, control over land could not be ensured unless one secured the nearby forts and garrisoned them, so as to repulse any possible return of the enemy. Controlling strong fortresses was hence the key to the control of territory. Since controlling riverine channels was crucial to achieving domination over the enemy in amphibious warfare, fortified locations were extremely important in amphibious warfare as well. Thus, the control of the Indus Basin was entirely about controlling certain key towns, like Bhakkar, Sehwan and Thatta. In the case of the Mughals, the conquest of these cities proved to be coterminous with the dominance over the river basin. On the other hand, on a terrain infested much more with rivers and other water bodies, as in the Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta, rivers were the key to all types of communication, military as well as logistical. As such, even makeshift fortified locations could give a side enormous advantage in controlling riverine spaces. In the Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta, the river bed and its surroundings being abundant in soft mud, temporary forts could be quickly erected at strategic locations in order to control waterways. Although temporary and built within a very short period of time, and that too mostly by the cheap labour of local villagers and boatmen, the mud fort was famous for its strength. Built of riverside mud, its walls would not break when struck by a cannonball unlike stone ram- parts; instead, the force would be absorbed by the mud and the shot rendered quite harmless. Owing to such strength, these mud forts could be defended well even by a small garrison and could be occupied by a besieger only after great exertions. In their initial phase of campaigns, the Mughals could bring more and more river channels under their control only by demolishing the mud forts of their enemy.

They, in turn, were also quick to learn the strategic and military value of the mud fort and soon adopted the tactic themselves. That the Mughals understood the necessity of controlling waterways in the Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta by commanding river forts is clearly proven by several surviving Mughal riverine forts. These forts, in modern Bangladesh, are built of masonry and clearly represent an evolved form of the mud fort. These were probably built around the mid- seventeenth century by Mir Jumla to command river channels. They are pro- vided with artillery platforms, which the Mughals used to mount artillery pieces and thereby command the transport on the river. River forts like these, equipped with artillery, gave the Mughals strategic and military strength.

While marching along a river, the usual order of the march would be the war fleet sailing along the river with the land army accompanying it on both the banks. During battles, these two wings, the land force and the fleet, would assist and defend each other. The following example of a Mughal amphibious engagement with Udayaditya, the son of Pratapaditya of Jessore, may be cited here to illustrate a few typical features of amphibious warfare in Bengal at this time.

When the Mughal Army under Ghiyas Khan was marching down to Jessore against Pratapaditya, they were first opposed at Salka by his son, Udayaditya, who had built a strongly fortified mud fort for himself. In response to this, the Mughals decided to send their war fleet along the river, accompanied on either sides by a contingent marching along the banks. Mirza Nathan was placed at the head of one of the detachments moving on land, while Ghiyas Khan commanded the other. When Udayaditya’s force did not march out as the Mughals had expected them to, the two Mughal detachments on land started fortifying their own positions with mud forts. When this building process was midway, Udaya- ditya came out of his fort with his war fleet. Khwaja Kamal led the fleet in the van while Udayaditya commanded the centre, with the major contingent. The Baharistan mentions a variety of boats in his fleet, some among them being piara, kusa, balia, ghurabs and jaliya, and probably quite a few among them carried artillery pieces. Jamal Khan remained inside the fort as a back up with the contingent of elephants.

Udayaditya’s boats first met the 20 boats of the Mughal naval vanguard. The ghurabs of Khwaja Kamal’s vanguard and two piaras surrounded ten of the Mughal boats and pushed them back towards the bank where Ghiyas Khan was encamped. Some mansabdars from here dismounted and came down near the bank of the river and showered the enemy boats with arrows, to allow their own boatmen and soldiers to take cover. They succeeded in seizing a piara and a ghurabs in the process. In the face of this Mughal counterattack, the crew of these boats of Udayaditya jumped into the water to save themselves.

While Udayaditya’s fleet was harassing the Mughal naval van, Mirza Nathan and his land force came to their rescue. Finding that the land route for their cavalry was blocked, they started showering arrows on the enemy boats from the shore. In this way, he kept Udayaditya’s naval boats busy, and even pushed them back while his van moved forwards, and thus succeeded in dividing the enemy’s naval forces. In the engagements that followed, Khwaja Kamal was killed by a Mughal bullet. While both parties continued to exchange projectiles, Udayaditya’s men supposedly lost heart at the death of Khwaja Kamal and their boats retreated. As Udayaditya’s fleet headed in the opposite direction, six Mughal kusas chased him. Just when the Mughal kusas seemed to be closing in on Udayaditya, one piara, four ghurabs and one machua slowed down, anchored and engaged the kusas, giving the main fleet of Udayaditya some time to flee. Among these, the machua carried some `Firingis’, probably meaning Portuguese renegades in service of Udayaditya. A combined attack by the Mughal kusas along with a shower of arrows from Nathan’s land force defeated these boats and four of the Mughal boats engaged in looting them. The remaining two kusas renewed their pursuit, shooting arrows. Soon they neared Udayaditya’s fleet as the latter came to a narrow part of the river which compelled him to slow down to facilitate passage of the boats. As Udayaditya’s men fired their guns from their boats, the two Mughal kusas closed in on his Mahalgiri boat. As they touch the rear of the Mahalgiri, Udayaditya was rescued by the boatmen of a faster moving kusa and he successfully escaped with his wives. Nathan says that the Mughal kusas did not pursue him any further because they had already boarded the Mahalgiri leaving their kusas behind when Udayaditya fled and also as they busied themselves looting that boat. Mirza Nathan, having no boat at hand while the enemy escaped, was left despondent.

Boats

The Mughal army did not care for boats much before the 1570s. The Baburnama tells us how Babur used to have wild drinking parties in his boats on the Indus in his pre- Panipat days while he was still the lord of Kabul; but the military necessity to build a riverine fleet first arose in the 1570s, when they started campaigning in the Indus and Ganga basins. The first large contingent of boats was prepared when Akbar decided to sail downstream along the Ganga to supervise the siege of Patna in 1574. While the main army would march along the banks, the emperor decided to advance by the river with the ladies of his harem and his select courtiers. A large contingent of boats was procured for the purpose. From the description provided in contemporary sources, these boats were massive, ornate and diverse in shape. There were several types of boats. Some were residential, used for carrying Akbar and his family members, while others carried his political elite and their families and offices. Some boats carried military and logistical equipment, treasury, wardrobes, carpets, animals to be used in battles and hunting. Animals transported by boats included around 500 elephants. It must have required a very large number of boats to carry them, as a single boat could carry three elephants at most. Apart from these, there were large boats, called ghurabs, fitted with cannons and fully equipped for war. A fascinated Abul Fazl describes how the sterns of the boats were built in the shape of animals and some bigger vessels even had gardens on them. The main body of the crew was known as kharwaha, who are described as a social group linked with riverine transportation. While the Mughal Navy had an official Mir Bahr, or commandant of the fleet, these boatmen were recruited on an ad hoc basis.

Eager to expand their resources of boats, the Mughals welcomed any potential ally who could strengthen them in this respect. In the Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta in 1586, the Arakan ruler of northern Burma sent the Mughal governor of Bengal presents, including elephants, which were held in high value both valuable militarily and symbolically in both Bengal and Burma, as a diplomatic gesture. Abul Fazl’s comment, quoted earlier, in the context of the description of this incident betrays the relief at the settlement of peace with a militarily and logistically superior power. This attitude of healthy respect of the Mughals towards another contending political power was not very typical of them. The Gangetic Delta, however, was an entirely different terrain (literally so), as the Mughal cavalry that dominated the plains of the northern parts of the subcontinent were practically crippled here owing to the aquatic body dominated topography. Again, in 1596, Lakshminarayan, the Raja of Kuch Bihar surrendered to the Mughals. Abul Fazl mentions him having 4,000 cavalry, 2,000,000 infantry, 700 elephants and, more importantly, 1,000 war boats. The Mughals found in him an important ally to the north of Ghoraghat and also against the Isa Khan clique. His war fleet provided much needed support to the meagre Mughal resources in this respect. Boats formed a regular and prized form of war- booty and apart from the boats built or hired by the Mughals, boats captured from the enemy or obtained as tribute from a subordinate ally formed an important part of the Mughal fleet.

Mughal resources in terms of boats increased dramatically once they established themselves in the eastern parts of the Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta. It was probably in this period, when the Mughals penetrated the Bengal Delta far beyond their base in Dhaka and engaged and ultimately defeated their enemies following a policy of all out military aggression, that a proper Mughal war fleet was formed for the first time under the initiative of Islam Khan, the then subahdar of Bengal. Baharistan mentions a whole range of indigenous boats used by the Mughal Army during their campaigns of 1608-1612. These include kusa, khelna, katari, maniki, bachila, jaliya, dhura, sundara, bajra, piara, balia, pal, ghurab, machua, pashta etc. Some of these, like ghurab, maniki and katari were used as war boats and fitted with artillery pieces of different range and weights. Others were used for transporting men, animals and supplies. Merchant boats, loaded with supplies, also probably accompanied the Mughal war fleet, keeping the army supplied. The ones among the bara bhuiyan (12 warlords) who were defeated and absorbed into the rubric of Mughal service joined the Mughals with their own war fleets during military expeditions.