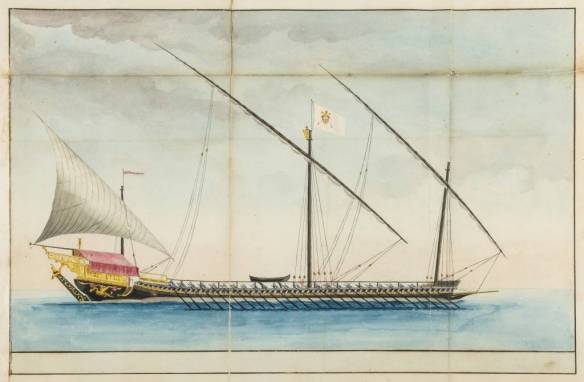

Capitana Pontificia (flagship of the Papal Navy which fought at the Battle of Lepanto, 1571)

An occasional force in the containment of Islam. From the early eighth through the late nineteenth centuries, what can be termed a papal navy existed sporadically. The chief purpose for such a navy was to halt the spread of Islam in the Levant and the Mediterranean. This navy was, more often than not, a collection of men and ships subsidized or authorized by the papacy but operated by other Christian powers to support papal policies.

For centuries the Muslim Saracens raided Christian territories and captured them to use as slaves. Popes and emperors were concerned about such depredations but usually did not maintain any type of standing force to stop them. There were a few exceptions. In 877, for example, Pope John VIII raised a fleet of galley-like ships, known as dromone, to defend Christian interests. This fleet, however, was short-lived and did not solve the problem.

After the popes preached the crusades, a renewed interest in building naval assets to further this effort emerged. In 1201 the Venetians agreed to transport the crusaders of the ill-fated Fourth Crusade to Egypt, whence they would then launch themselves on the road to Jerusalem. This crusade went awry, and the crusaders seized first a portion of the Adriatic coast and then Constantinople itself, but it illustrated how the pope might put naval resources to use.

In 1213 Pope Innocent III authorized King Philip II (Augustus) of France to cross the English Channel and invade England, after he had excommunicated King John and declared him deposed. This invasion did not occur, as John made amends and Innocent lifted the ban; but, again, this was an instance of papal intent to use a naval force.

With the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, papal concern over possible Islamic domination increased. Pope Pius II (1458-1464) wanted to create an actual papal navy that might stem the Islamic tide. This navy did not materialize, but the pope believed a need existed and hoped to lead the charge against Islamic expansion into Europe.

One of Pius II’s successors, Pius V (1566-1572), brought the concept of a papal navy to its highest point. On his election in 1566, Pius V immediately provided funds to Philip II of Spain to strengthen the Spanish Navy in order that it might contain the Turkish fleet, which then threatened to dominate the Mediterranean. Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, and the papacy had a common interest in suppressing the Islamic impulse, but France and England had their own strategic interests vis-a-vis the Spanish and Catholicism respectively. Thus, the leaders of the Christian world were divided. By 1570, however, Pius V had emerged as the dominant voice in anti-Turk negotiations, and he brought the Venetians into the fray. These negotiations resulted in first a temporary alliance with papal subsidies for the Venetian navy and then a formal alliance in early 1571, the Holy League.

Ultimately, the Holy League went to war against the Turks and defeated them in the greatest battle of galleys since Actium, the 7 October 1571 Battle of Lepanto. It was, unquestionably, the high point of the papal navy. The Christian fleet at the battle comprised 207 galleys, 6 galeasses, and 24 cargo vessels. All but a few were from the pope. The Ottoman fleet was made up of about 250 galleys. The Christians had upwards of 44,000 seamen and 28,000 soldiers from Venice, Spain, Genoa, Savoy, Malta, and the Papal States. Turkish seamen numbered some 50,000, along with some 25,000 soldiers. The casualty count, both in men and ships, is widely disputed, but the Turks lost over 200 galleys and 20,000 dead. The Christians put their own losses at 12 ships, with 7,500 dead and 15,000 wounded.

Although the Ottoman fleet was rebuilt, after the Battle of Lepanto the papal navy was essentially involved with curbing the activities of Muslim pirates who haunted the waters of the Mediterranean until 1830. A papal navy, either subsidized or authorized, managed to survive until the late nineteenth century when Pope Leo XIII (1878-1903) dismantled it as a useless vestige of the times when the popes competed stridently for temporal power.

References Braudel, Fernand. The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Vols. 1, 2. Trans. Sian Reynolds. New York: Harper & Row, 1966. Guglielmotti, P. Alberto. Marcantonio Colonna alla battaglia di Lepanto. Firenze: Felice Le Monnier, 1862. —. Storia della Marina Pontificia. Vols. 1-10. Rome: Tipografia Vaticana, 1886-1893.

Papal Naval Flag

https://theflagandanthemguy.deviantart.com/art/Papal-Naval-Flag-496517175