Finnish troops with Panzerfausts

The Last Phase

On 21 June the Russians occupied Vyborg, which the Finns had evacuated a day earlier. Although there had been no intention to defend the old city, its loss was a blow to Finnish morale. Between Vyborg and the Vuoksi, Russian pressure continued heavy, and on 25 June they threw ten divisions reinforced by assault artillery against the front near Repola, penetrating the line to a distance of some two and one-half miles. In four days of heavy fighting the Finns managed to seal off the penetration but without restoring their former front. The Russians remained in possession of a salient which was the more dangerous in that it brought them close to terrain favorable for armored operations.

On 16 June Mannerheim had issued orders for withdrawal from East Karelia. The intention was to pull back gradually from the Svir and Maaselka lines to the general line Uksa River-Suo Lake-Poros Lake. At the last minute, as the withdrawal was starting, the OKW tried without success to persuade him not to give up East Karelia. In this respect the OKW directly contradicted the advice which Dietl had given. Its decision to do so probably rested on several considerations. In the first place, it had become an obsession with Hitler never to give ground voluntarily. Even more important in this instance was the fact that in giving up East Karelia the Finns would lose their principal war gain, their last lever for bargaining with the Soviet Union, and, consequently, their motivation for remaining in the war. Furthermore, with a major offensive in the offing on the Eastern Front, it could be assumed that the Russians would stop short of an all-out effort at a decision in Finland. The OKW line of reasoning had much to recommend it-from the German point of view but not from the Finnish. The Finns had no taste for desperate gambles and, for that matter, although they seemed to be acting in agreement with Dietl’s recommendations, neither had they any enthusiasm for last stands in the Goetterdaemmerung vein.

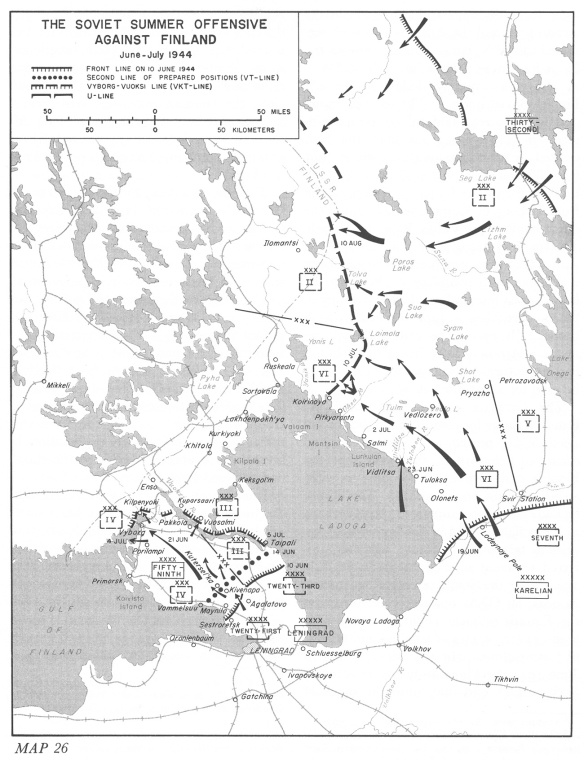

In the Maaselka and Aunus (Svir) Fronts the Finns had a total of four divisions and two brigades. Opposite them stood eleven Russian divisions and six brigades. By evacuating their large bridgehead south of the Svir on 18 June they escaped a Russian attack which began the following day, but thereafter the withdrawal went less smoothly than had been expected. The Russians kept up an aggressive pursuit and, by crossing the Svir on either side of Lodeynoye Pole and staging a landing on the Ladoga shore between Tuloksa and Vidlitsa, threatened to push the Finnish divisions back into the wilderness on the eastern side of the Isthmus of Olonets. On 30 June the Finns evacuated Petrozavodsk, and two days later they pulled out of Salmi. By 10 July the Finnish divisions were in the U-Line. With Russian pressure continuing strong, the Finns were by no means certain that they could hold the front, and they began work on new positions between Yanis Lake and Lake Ladoga. A further withdrawal to the Moscow Line also came under consideration.

In the first days of July the Finns were given a short respite, at least on the Isthmus of Karelia. On the 4th the Russians occupied the islands in Vyborg Bay and attempted a landing on the north shore. There they ran into the 122d Infantry Division, which was moving up, and were thrown back. At the same time they attacked the Finnish bridgehead south of Vuosalmi, but otherwise they confined themselves to local attacks and regrouping, giving the Finns an opportunity to strengthen their defenses.

In the Finnish High Command concern for the future was growing, particularly with respect to manpower. At the end of June casualties had reached 18,000, of which only 12,000 could be replaced. On 1 July Mannerheim asked for a second German division and additional self-propelled assault gun units. When Hitler countered with nothing more than a promise to build the assault gun battalion of the 122d Infantry Division up to brigade strength Mannerheim protested that in advising his Government to accept the German proposals during the June negotiations he had assumed a heavy responsibility; if the German units were not forthcoming, not only would the military situation deteriorate, but his political prestige would be destroyed. Hitler, in reply, offered one self-propelled assault gun brigade before 10 July, another to be sent later, and tanks, assault guns, antitank guns, and artillery.

In the second week of July the Finns were forced to give up their positions on the right bank of the Vuoksi south of Vuosalmi. The Russians, in turn, gained a bridgehead of their own on the north bank. Lacking the strength to eliminate the bridgehead, the Finns had to undertake to contain it. Despite this dangerous development and continued heavy fighting which brought the number of Finnish casualties up to 32,000 by the 11th, the fronts on both sides of Lake Ladoga were beginning to stabilize. By 15 July the Finns had detected signs-confirmed several days later-that, although the Russian strength on the Isthmus had risen to 26 rifle divisions and 12 to 14 tank brigades, the first-rate guard units were being pulled out and replaced with garrison troops. It could be expected that the tempo of the offensive would be reduced.

While the Finns achieved a degree of equilibrium in the second-half of the month, the Army Groups North and Center were experiencing a full-scale disaster. In three weeks the Russian offensive had driven the Army Group Center back into Poland and nearly to the border of East Prussia. By mid-July the time had come to pull the Army Group North back behind the Dvina or see it cut off and isolated in the Baltic States. Hitler’s solution was to place Schoerner, then a Generaloberst, in command of the army group with orders to hold the old PANTHER Line between Narva and Pskov at all costs.

On 17 July Hitler dispatched one of the self-propelled assault gun brigades promised the Finns to the Eastern Front instead and sent the second one east also on the following day. These decisions were not communicated to Mannerheim until several days later-after the Soviet troop withdrawals from the front in Finland had been confirmed.

To the Finns the fate of the Army Group North was nearly as momentous as that of their own Army. Once the Baltic coast was in Russian hands their supply lines to Germany, on which they depended for much of their food and almost all of their military supplies, could be cut. The loss of Pskov on 23 July and of Narva on the 27th were staggering blows for them. The shock was intensified when, two days after the fall of Narva, Hitler ordered the 122d Infantry Division back to the Army Group North. Mannerheim asked that the division leave via Hanko rather than Helsinki in order to avoid alarming the people. The OKW explained that the deciding factor had been the relative quiet on the Finnish front and assured him that he could count on German help in any new crisis, but under the circumstances these explanations must have had a decidedly empty ring.

Armistice

In a secret meeting on 28 July in Mannerheim’s country house at Sairala, Ryti announced his intention to resign and urged Mannerheim to accept the presidency of Finland. Three days later the resignation was submitted, and Parliament drafted a law, passed unanimously on 4 August, elevating Mannerheim to the presidency without the formality of an election. With that, the stage was set for a repudiation of the Ryti-Ribbentrop agreement and a new approach to the Soviet Union.

To the Germans Ryti’s resignation came as a surprise. – They assumed that the shift would not be advantageous to Germany. Although they saw a possibility that Mannerheim might intend to rally the national will to resist, it appeared more likely that he would assume the role of a peacemaker. Apprehensive, but powerless to exercise any real influence over the course of Finnish policy, the Germans in near-panic hastened to reassure Mannerheim. On 3 August, in response to a Finnish inquiry concerning the situation in the Baltic area, the OKW ordered the Commanding General, Army Group North, Schoerner, to report to Mannerheim in person immediately. Keitel was to follow in a few days. The Schoerner visit surprised nearly everyone, including Schoerner himself who asked Erfurth why he had been rushed off to Helsinki in such head-over-heels fashion. The Finns took Schoerner’s sudden appearance as a sign of nervousness and as a too obvious attempt to court Mannerheim.

To draw even mildly encouraging conclusions from the situation of the Army Group North required a man of Schoerner’s zeal and determination. Although Narva and Pskov had fallen, most of the NarvaPeipus line was still in German hands; but, at the turn of the month, the Russians had thrust through to the Baltic near Mitau cutting off and isolating the army group. The ominous nature of this development was underscored when the Lufthansa suspended air traffic between Germany and Finland. Direct telephone communications had been broken several days earlier. Undaunted, Schoerner promised that the Baltic area would absolutely be held; the Army Group North would be supplied by air and by sea; and armored forces from East Prussia would restore the land contact. Remarkably enough, largely as a result of the combined wills of Schoerner and Hitler pitted against the logic of events, the promise was kept; but, even though Schoerner left Mannerheim with the impression that his report had had a positive effect, it appears that his success, if any, was transitory. Still, the German determination-more specifically, that of Hitler and Schoerner with an assist from the Navy in the interest of submarine warfare-to hold the Baltic shore at all costs was of very material benefit to Finland, not in encouraging the nation to remain in the war but in affording it an opportunity to make peace before it was completely isolated.

With the Army Group North making its stand on the shores of the Narva River and Lake Peipus and with the Soviet summer offensive degenerating into local attacks on the Isthmus of Karelia, the military position of Finland in August was, if only for the time being, as favorable as even a confirmed optimist would have dared predict a month or so earlier. Between mid-July and mid-August the Russians reduced their forces on the Isthmus by 10 rifle divisions and 5 tank brigades. On 10 August in East Karelia the Finnish Army ended its last major operation in World War II with a victory when the 14th Division, the 21st Brigade, and the Cavalry Brigade trapped and nearly destroyed Russian divisions in a pocket east of Ilomantsi. It appeared that as in the Winter War, although the Soviet Union could claim a victory, its offensive had failed, largely for the same reasons-underestimation of the Finnish capacity to resist and rigid, unimaginative Soviet tactical leadership.

Mannerheim believed that in their eagerness to destroy Finland the Russians betrayed their promise to the Western Powers to assist the Normandy landings and weakened their own offensives against the Army Groups Center and North. In the absence of reliable Soviet sources no definite conclusions concerning their intentions can be drawn. It is unlikely that the offensive against Finland was undertaken with deliberate disregard for a promise to aid the landings in Normandy with an offensive in the east. The offensive in Finland was a secondary effort and was probably staged to fill in time while Stalin waited, first, to see whether the Allies would actually invade the Continent and, then, to make certain that the invasion was in earnest and had prospects of success. Probably, the success of the invasion influenced Stalin to give up his excursion into Finland and to devote all of his efforts to the race for Berlin.

By the time Keitel went to Helsinki (17 August), carrying an oak leaf cluster for Mannerheim and a Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross for Heinrichs, the German situation offered little to sustain even his indomitable optimism. The Allied breakout in Normandy had succeeded, and the liberation of Paris was only days away. In southern France the Allies were rapidly developing a secondary offensive. In Italy the Germans were driven back to the Gothic Line; in the East the Russians stood on the outskirts of Warsaw. The end for Germany suddenly seemed very close, much closer than it actually was.

Mannerheim, for his part, took the Keitel visit as an opportunity to clear the air, possibly not so much for the Germans’ benefit as to open the way for a new approach to Moscow. The 60,000 casualties incurred during the summer, he said, had been replaced, but Finland could not endure a second bloodletting on that scale. Turning to what was probably also uppermost in Keitel’s mind, the status of the Ryti-Ribbentrop agreement, he stated that Ryti, in a desperate situation, had made a contract which proved highly unpopular. Finland believed that Ryti’s resignation nullified that contract. Keitel, taken aback by that blunt statement, in order to protect Germany’s legal interests, rejected it stating that he was not empowered to receive political communications.

In Finland, after the middle of the month, signs of the approaching end mushroomed on all sides. Peace sentiment increased with every passing day, and rumors of all sorts gained currency. In this atmosphere the report that Rumania had sued for peace struck like a bombshell. On 25 August, through its legation in Stockholm, Finland asked whether the Soviet Government would receive a Finnish peace delegation. An accompanying verbal note informed the Soviet Government that Mannerheim had told Keitel he did not consider himself bound by the Ryti-Ribbentrop agreement. Official notice that Finland had repudiated the agreement was not sent to Germany until the following day.

In its reply on 29 August the Soviet Government made its willingness to receive a delegation contingent upon the prior fulfillment of two conditions: that Finland immediately break off relations with Germany and that Finland order all German troops to leave its territory within two weeks, at the latest by 15 September, and, in case of the Germans’ failure to comply, take steps to intern them. The Finnish Parliament accepted the conditions on 2 September, and on the same day approved a government motion to break off relations with Germany.

The Finnish decision came as somewhat of a surprise to the Germans. Although the German Minister in Helsinki had been informed on 31 August that negotiations were in progress, it was expected that the Soviet terms would prove unacceptable. Several times in the past a glance at the Soviet terms had proved the best means of inhibiting the Finnish sentiment for peace. On 2 September, in a last minute, heavy-handed effort to give impetus to a repetition of that pattern, Rendulic called on Mannerheim and emphasized in particular that the Russian demands might bring about a conflict between German and Finnish troops which, he maintained, would result in 90 percent losses on both sides since the best soldiers in Europe would be opposing each other.

Two problems which worried the Finnish leadership as the end approached proved less serious than they might have been. The first of these was the danger of an economic collapse when German assistance stopped. It was solved in August when Sweden agreed to cover the requirements of grain and some other foodstuffs for a six-month period. The second, the possibility that some elements of the population, particularly in the Army, would refuse to accept the peace and would create internal dissension or throw their lot in with the Germans, although it occasioned some apprehension, never actually arose. During the last months, the Germans had toyed with a number of ideas for keeping Finnish resistance alive by extralegal means. In June, when he went to Helsinki, Ribbentrop had proposed, somewhat wildly, that the German Minister find a thousand reliable men to take over the government. At the same time, Hitler had instructed Dietl to draw Finnish troops into the Twentieth Mountain Army in the event of a separate peace. Later Rendulic suggested that the German infantry division and assault gun brigade in southern Finland be used as a nucleus around which a resistance movement could be built and in August proposed General Talvela as a man who might be persuaded to lead the resistance. None of these projects passed beyond the talking stage, and one that was later tried, reactivation of the traditional Finnish 27th Jaeger Battalion (in the German Army), attracted only a scattering of volunteers. The overwhelming majority of the Finnish population was willing to follow its government, and the Finnish Government had been careful throughout the war to prevent the emergence of possible Quislings.

Having met the Soviet conditions, the Finns appointed an armistice delegation-which, as it developed, would have to negotiate the terms of peace as well-headed by Minister President Antti Hackzell. Mannerheim undertook to explain the Finnish action in a personal letter to Hitler in which he expressed gratitude for the German help and loyal brotherhood-in-arms and stated that, while Germany could never be completely destroyed, the Finns could, both as a people and a nation; therefore, Finland had to make peace in order to preserve its existence. Next, he turned to Stalin, proposing a cease fire to prevent further bloodshed while the negotiations were in progress. Both sides accepted 0700 on 4 September as the time; but, although the Finns stopped their operations on time, the Russians, either through a mistake or to underscore their victory, let theirs run another 24 hours.

The delegation reached Moscow on 7 September, but the Soviet Government delayed a week before presenting its terms. Restoration of the 1940 border was a foregone conclusion. In addition, the Russians demanded the entire Pechenga region and, in place of Hanko, a fifty-year lease on Porkkala, which would give them a base astride the main rail and road routes to southwestern Finland within artillery range of Helsinki. The reparations were set at $300,000,000 to be paid in goods over a five-year period. The Finnish Army was to withdraw to the 1940 border within five days and be reduced to peacetime strength within two and one-half months. The Soviet Union was to be granted the right to use Finnish ports, airfields, and merchant shipping for the duration of the war against Germany; and a Soviet commission would supervise execution of the armistice, which was to become effective on the day it was signed.

On 18 September the Finnish Cabinet took the terms under consideration but could not reach an agreement. The Russians, meanwhile, demanded that the signing be completed by noon of the following day. Early on the morning of the 19th, after the Army informed the Cabinet that under the most favorable circumstances Finland could not continue the war for more than another three months, the Parliament gave its approval. In Moscow the Finnish delegation signed the armistice shortly before noon, before it had received the official authorization.