Henry IV and the war of Savoy

In exchange for retaining Saluzzo (dotted area, lower center), Savoy was compelled to cede most of its territories on the far side of the Rhône (striped area, upper left)

The peace of Vervins was not very well observed on the part of France. The ruling idea which guided the foreign policy of Henry IV was to curb the power of the House of Austria: a plan incompatible with the letter of the treaty. In pursuance of this policy Henry became the supporter of Protestantism; not, perhaps, from any lingering affection for his ancient faith—his indifference in such matters has been already seen—but because the Protestants were the natural enemies of the Austrian House. Hence he was determined to support the independence of Holland. He annually paid the Dutch large sums of money; he connived at the recruiting for them in France; and in spite of a royal prohibition, granted at the instance of the Spanish ambassador in 1599, whole regiments passed into the service of the United Provinces. In aid of these plans Henry fortified himself with alliances. He courted the Protestant Princes of Germany, and incited them to make a diversion in favour of the Dutch; he cultivated the friendship of Venice, reconciled himself with the Grand Duke of Tuscany, and attached the House of Lorraine to his interests by giving his sister, Catharine, in marriage to the Duke of Bar (January 31st, 1599); who, formerly, when Marquis of Pont-à-Mousson, had been his rival for the French Crown, and who in 1608 succeeded his father as Duke of Lorraine. The Porte was propitiated by Savary de Brèves, an able diplomatist; and the vanity of France was gratified by obtaining the protectorate of the Christians in the East. The Pope was gained through his temporal interests as an Italian Prince. Henry had promised, on his absolution, to publish in France the decrees of Trent; and, as he had refrained from doing so out of consideration for the Huguenots, he had, by way of compensation, offered to support Clement VIII in his design of uniting Ferrara to the immediate dominions of the Church; although the House of Este had often been the faithful ally of France. The direct line of the reigning branch of that family becoming extinct on the death of Duke Alfonso II, Clement VIII seized the duchy; and Caesard’Este, first cousin and heir of Alfonso, obtained only the Imperial fiefs of Modena and Reggio (1597). The connivance of Henry gratified the Pope and caused him to overlook the Edict of Nantes.

The friendship of the Pope was also necessary to Henry for his private affairs, as he was meditating a divorce from his wife, Margaret of Valois, from whom he had long been estranged, and who had borne him no children. Flaws were discovered in Gregory XIII’s dispensation for kinship; and as Margaret herself, in consideration of a large pension from the King, agreed to the suit (July, 1599), a divorce was easily obtained. The choice of her successor was more difficult. Mary de’ Medici, the offspring of Francis, Grand-Duke of Tuscany, by a daughter of the Emperor, Ferdinand I, was proposed, and supported by Sully who opposed all idea of a marriage with Gabrielle, now Duchess of Beaufort. The difficulty was solved by the sudden death of Gabrielle, April 10th, 1599. Henry, who was absent from Paris, though he felt and displayed an unfeigned sorrow for the death of his mistress, harbored no suspicions, and the negotiations for the Florentine marriage went on. Mary de’ Medici, however, was nearly supplanted by another rival. Before the end of the summer, Henry had been captivated by a new mistress, Mademoiselle d’Entragues, whom he created Marquise de Verneuil. The Papal commissaries had, in December, 1599, pronounced his marriage with Margaret null; and on the 25th of April following the King signed his marriage contract with the Tuscan Princess, the second descendant of the Florentine bankers, who was destined to give heirs to the Crown of France.

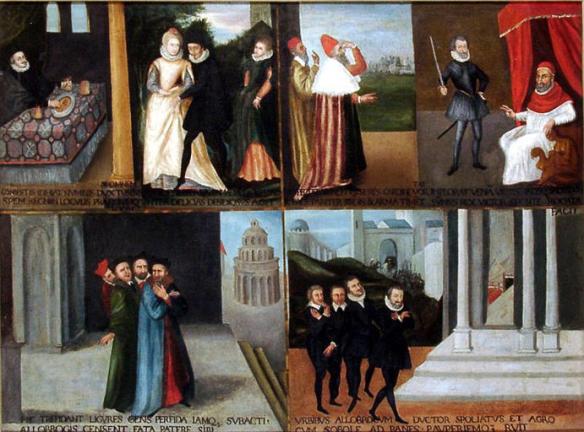

A domestic rebellion, fomented by Spain and Savoy, diverted awhile the attention of Henry from his plans of foreign policy. Sully’s economy and love of order had excited much discontent among the powerful nobles of France; the materials of sedition were accumulated and ready to burst into a flame; and a point that had been left undecided in the treaty of Vervins afforded the means of applying the torch. By that treaty the question between France and Savoy respecting the Marquisate of Saluzzo had been referred to the decision of the Pope; but Clement VIII, unwilling to offend either party, had declined to interfere. In order, if possible, to settle this question, and also to engage Henry to support his pretensions to Geneva, Charles Emmanuel, who then reigned in Savoy, paid a visit to the French King at Fontainebleau; where, alarmed apparently at the idea of being seized and detained, he agreed to decide whether he would give up Bresse in exchange for Henry’s claims on Saluzzo. He had, however, no intention of surrendering either the one or the other; and he employed his visit to France in ingratiating himself with the French nobles, many of whom he gained by large gifts and still larger promises. It had been predicted by an astrologer that in the year 1600 there should be no King in France; and Charles Emmanuel made use of a prediction which, in that age, earned no slight weight, not only to rouse the ambition of the French nobility, but also, it is said, to stimulate a renewal of the odious enterprises against Henry’s life. A plan was formed to convert France into an elective monarchy, like the Empire, and to establish each great lord as an hereditary Prince in his government. It was thought that many towns as well as nobles might be drawn into the plot, nay, even that some princes of the blood might be induced to engage in it. Among the leading conspirators were the Dukes of Epernon and Bouillon (Turenne), and the Count of Auvergne, a natural son of Charles IX and uterine brother of the King’s mistress, Henriette d’Entragues. But Marshal Biron was the soul of the plot: whose chief motive was wounded pride, the source of so many rash actions in men of his egregious vanity. Biron pretended that the King owed to him the Crown, and complained of his ingratitude, although Henry had made him a Duke and Peer, as well as a Marshal of France and Governor of Burgundy. Henry had mortified him by remarking that the Birons had served him well, but that he had had a great deal of trouble with the drunkenness of the father and the freaks and pranks of the son.Biron’s complaints were so loud that the Court of Spain made him secret advances; while an intriguer named La Fin proposed to him, on the part of the Duke of Savoy, one of the Duke’s daughters in marriage, and held out the hope that Spain would guarantee to him the sovereignty of both Burgundies. After many pretexts and delays, Charles Emmanuel having refused to give up Bresse for Saluzzo, or Saluzzo for Bresse, Henry IV declared war against him in August, 1600, and promptly followed up the declaration by invading Savoy. Biron carefully concealed his designs, nor does the King appear to have been aware of them; for he gave the Marshal a command, who conquered for him the little county of Bresse, though still secretly corresponding with the Duke of Savoy. Henry’s refusal to give Biron the command of Bourg, the capital of Bresse, still further exasperated him.

One of the most interesting incidents of this little war is the care displayed by Henry for the safety of Geneva. The Duke of Savoy had long hankered after the possession of that city, and had erected, at the distance of two leagues from it, the fort of St. Catherine, which proved a great annoyance to the Genevese. The fort was captured by the royal forces; and the now aged Beza, at the head of a deputation of the citizens, went out to meet the King, who, in spite of the displeasure of the Papal Legate, gave him a friendly reception, presented him with a sum of money, and granted his request for the demolition of the fortress. This war presents little else of interest except its results, embodied in the treaty of peace signed January 17th, 1601. The rapidity of Henry’s conquests had quite dispirited Charles Emmanuel; and although Fuentes, the Spanish Governor of the Milanese, ardently desired the prolongation of the war, the Duke of Lerma, the all-powerful minister of Philip III, was against it; for the anxiety of the Spanish cabinet had been excited by the appearance of a Turkish fleet in the western waters of the Mediterranean, effected through the influence of the French ambassador at Constantinople. Under these circumstances negotiations were begun. In order to retain the Marquisate of Saluzzo, which would have given the French too firm a footing in Piedmont, the Duke was compelled to make large territorial concessions on the other side of the Alps. Bresse, Bugei, Valromei, the Pays de Gex, in short, all the country between the Saone, the Rhone, and the southern extremity of the Jura mountains, except the little principality of Dombes and its capital Trevoux, belonging to the Duke of Montpensier, were now ceded to the French in exchange for their claims of the territories of Saluzzo, Perosa, Pinerolo, and the Val di Stura. The Duke also ceded Chateaux-Dauphin, reserving a right of passage into Franche-Comte, for which he had to pay 100,000 crowns. This hasty peace ruined all Biron s hopes, and struck him with such alarm, that he came to Henry and confessed his treasonable plans. Henry not only pardoned him, but even employed him in embassies to England and Switzerland; but Biron was incorrigible. He soon afterwards renewed his intrigues with the French malcontent nobles, and being apprehended and condemned for high treason by the Parliament of Paris, was beheaded in the Court of the Bastille, July 29th, 1602. The execution of so powerful a nobleman created both at home and abroad a strong impression of the power of the French King.

While the war with Savoy was going on, Mary de’ Medici arrived in France, and Henry solemnized his marriage with her at Lyons, December 9th, 1600. The union was not destined to be a happy one. Mary was neither amiable nor attractive; she possessed but little of the grace or intellect of her family; and was withal ill-tempered, bigoted, obstinate, and jealous. On September 27th, 1601, the Dauphin, afterwards Louis XIII, was born.

Although the aims of Henry IV were as a rule noble and worthy of his character, the means which he employed to attain them will not always admit of the same praise. His excuse must be sought in the necessities and difficulties of his political situation. At home, where he was suspected both by Catholics and Huguenots, he was frequently obliged to resort to finesse, nor did he hesitate himself to acknowledge that his word was not always to be depended on. Abroad, where his policy led him to contend with both branches of the House of Austria, he was compelled, in that unequal struggle, to supply with artifice the deficiencies of force; and he did not scruple to assist underhand the malcontent vassals and subjects of the Emperor and the King of Spain. France is the land of political “ideas”, and Henry, or rather his Minister, Sully, had formed a magnificent scheme for the reconstruction of Europe. Against the plan of Charles V and Philip II, of a universal THEOCRATIC MONARCHY, Sully formed the antagonistic one of a CHRISTIAN REPUBLIC, in which, for the bigotry and intolerance supported by physical force, that formed the foundation of the Spanish scheme, were to be substituted a mutual toleration between Papists and Protestants and the suppression of all persecution. Foreign wars and domestic revolutions, as well as all religious disputes, were to be settled by European congresses, and a system of free trade was to prevail throughout Europe. This confederated Christian State was to consist of fifteen powers, or dominations, divided according to their constitutions into three different groups. The first group was to consist of States having an elective Sovereign, which would include the Papacy, the Empire, Venice, and the three elective Kingdoms of Hungary, Poland, and Bohemia. The second group would comprehend the hereditary Kingdoms of France, Spain, Great Britain, Denmark, Sweden, and the new Kingdom of Lombardy which was to be founded; while the Republics or federate States, as the Swiss League, the contemplated Belgian commonwealth, and the confederacy of the Italian States would form the third. The Tsar of Muscovy, or as Henry used to call him, the “Scythian Knès”, was at present to be excluded from the Christian Republic, as being an Asiatic rather than a European potentate, as well as on account of the savage and half barbarous nature of his subjects, and the doubtful character of their religious faith; though he might one day be admitted into this community of nations, when he should think proper himself to make the application.