For thousands of years, sailors found their way over vast seas by using a sextant to measure the angle between the horizon and heavenly bodies like the sun and the moon. Such measures told longitude and latitude, invaluable for determining the position of a ship. In the late twentieth century, these methods changed. Modern sailors use a navigation system that relies on satellites — artificial celestial bodies — to find their way. Navigation satellites launched by the U.S. Air Force circle the globe, sending radio signals that are “translated” by a Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver. GPS receivers are now standard in many handheld devices, like smartphones and tablets, and are included in many car dashboards to help drivers navigate highways and city streets.

Beyond its everyday use, GPS has become the U.S. military’s “backbone for its battlefield communications system.” Operation DESERT STORM, the second phase of the Gulf War, was the first conflict in which GPS was widely used. During the Gulf War, there was a “maximum of one receiver per company of 180 men.” Ten years later, in the Iraq War, there were “more than 100,000 Precision Lightweight GPS Receivers . . . for the land forces and at least one per nine-man squad.”

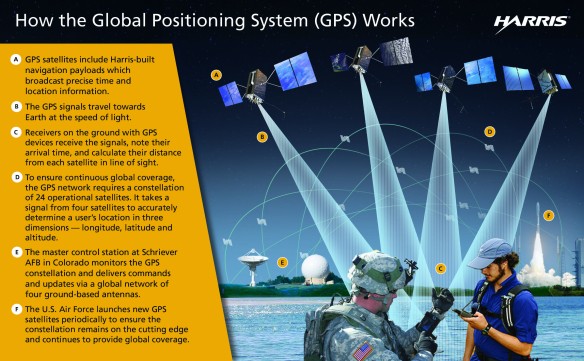

At the time of DESERT STORM, GPS relied on a “constellation” of twenty-seven satellites (twenty-four in operation and three spares) that circled the earth at an elevation of about twelve thousand miles in four evenly spaced orbits, making two complete orbits every day. There are now thirty-two satellites, allowing for even better reception, with six visible at any one time. Each satellite weighs between three thousand and four thousand pounds and orbits the earth at about nine thousand miles per hour, broadcasting a signal with two bits of information: the precise time on its atomic clock and the satellite’s exact location. A GPS receiver then uses simultaneous readings from three different satellites to determine its longitude and latitude, or its exact location on the earth. GPS needs to be equipped with mapping software that can read the information from the satellite and plot location and movement.

It was this GPS mapping ability that allowed the troops and equipment of the Coalition forces to move so confidentially without regard to road signs or physical markers. The Iraqis were amazed that the enemy could “own the night” and move through adverse weather conditions, such as sandstorms. The U.S. military found GPS to be a “godsend for ground troops traversing the desert, especially in the frequent sandstorms. . . . Tank crews and drivers of all sorts of vehicles swore by the system.” But the usefulness of GPS extended beyond actual combat. Even trucks carrying meals to the troops were GPS-equipped, allowing drivers to “find and feed soldiers of frontline units widely dispersed among the dunes.”

#

While the wars in Korea and Vietnam were fought, as the U.S. military believed, to block the spread of Communism and “win the hearts and minds” of the people in countries the U.S. thought it was helping, the Gulf War of 1990–1991 was about something more tangible — essential, in fact, for the world to function: oil. It began after an attempt by Iraq’s president, Saddam Hussein, to control a large share of the oil flowing from the Middle East.

Unlike the wars in Korea and Vietnam, deception played a significant part in the war against Iraq. However, the use of overwhelming firepower as the cornerstone of overall strategy did not change. The war began with a prolonged period of aerial bombardment. Nevertheless, the ground war hinged on the use of deception.

There were a number of factors that led the U.S. military to use deception in the Gulf War. First of all, the war involved a relatively small geographic area. Kuwait covers about seven thousand square miles, roughly the size of New Jersey. While the entire war wasn’t fought in Kuwait, it was limited to an area around this small country. A related consideration was the fact that the war was fought in a flat and open desert, a far cry from the mountains of Korea or the jungles of Vietnam.

Further, the U.S. had a firm conviction that, if Coalition troops could neutralize the Iraqi air force and pull off a battlefield deception, they would then have the upper hand in a ground war. The war, the U.S. military reasoned, could conclude in relatively short order, certainly nothing like the three years in Korea or the roughly twenty years in Vietnam. A short war would mean limited casualties. As General Barry McCaffrey said, “The whole notion is to bypass the enemy’s strengths and reduce the amount of bloodshed to us and to them.”

Finally, advanced technology made it easier for U.S. soldiers to deliver a knockout punch to the Iraqi army. The Global Positioning System (GPS) proved especially critical in pulling off deception in the desert.

When the Iraqis invaded Kuwait in 1990, the U.S. and other world powers were worried that if Saddam Hussein controlled the oil in Kuwait, he might next invade Saudi Arabia, a longtime friend of the U.S. If Saudi Arabia then fell, Iraq would control 20 percent of the world’s oil supply. U.S. president George H. W. Bush would not let that stand. In the five years prior to the war, U.S. oil consumption had crept steadily higher, from 15.7 thousand barrels per day to 17.3 thousand barrels per day. The Gulf War began with rhetoric and accusations, and ended with a remarkable one hundred hours of ground combat.