EARLY JANUARY 1943

Divisional commanders and officers of the Alpine Corps received little “official” news of the overall progress of the war while on the Don front. German liaison officers attached to the headquarters of each division provided their main sources of information. They could monitor radiograms transmitted from various German units operating in the region. It was only in this manner that commanders of the Alpine Corps heard about the encirclement of German troops in Stalingrad, the fall of the Romanian Third Army, the collapse and withdrawal of the Italian Eighth Army on their right flank, as well as assaults on the Hungarian Second Army to the north of their lines.

Lieutenant Egisto Corradi of the Julia Division wrote about the lack of verifiable news: “We didn’t know Stalingrad was now irreparably encircled and close to falling. We didn’t know 7,000 survivors out of 35,000 or more of the Italian Thirty-Fifth Corps remained encircled in Cerkovo, and Italian divisions, other than the Ravenna and Cosseria, were swept away from the front. We knew nothing about any of this even up to January 15….”

Between January 1 and 17, there was increased Soviet air surveillance and artillery fire across the Don, leading the alpini to believe it was only a matter of time before they would be attacked.

Across the Don on January 9, Revelli and his men could see Russian trucks and armored vehicles heading south with headlights turned on.

Toward January 10, alpini in the Vestone Battalion (Tridentina Division) began to hear ominous news. Two alpini in Sergeant Rigoni Stern’s unit who had gone to the kitchens to draw rations, overheard several mule drivers say the Russians had encircled the Alpine Corps. Reports based on radio scarpa (the rumor mill) created an uneasy atmosphere of anxiety and tension among the men. Several alpini even asked their sergeant to tell them how many kilometers existed between their strongholds and Italy. Rigoni Stern was also feeling uneasy. He had noticed Russians across the river were cutting brush and undergrowth at night to “widen their field of fire.” At night to the south, he could see flashes of light resembling “summer lightening.” At other times, he could hear what sounded like rolling wheels across the river. Nevertheless, rations and mail arrived on schedule.

One evening shortly after January 10, Lieutenant Moscioni, commander of the stronghold, told the sergeant he had received orders in the event the alpini should have to withdraw from the Don. There followed a careful examination of all automatic weapons. The alpini under his command turned their bunker into a virtual “workshop,” dismembering machine guns, mortars, and the heavy machine gun, cleaning them, and “retempering the springs to adapt them more to the cold.” Once tested, soldiers wrapped the “four machine guns, the heavy machine gun and the four 45mm mortars” in blankets and tent tarps to protect them from “the fine sand, which filtered into the dugout and penetrated everywhere.”

On the evening of January 15, units of the Tirano Battalion (Tridentina Division) received orders to “shunt all material to the rear, even weapons and stove emplacements, as if in a normal transfer. Mule drivers were sent back to their bases and [the battalion] went from one alarm to the next. Temperatures dropped below -40°.” To the south, the alpini could hear thunderous firing from the Edolo Battalion of the Tridentina. Revelli writes, “From company headquarters a strange order arrived; every alpino had to build a sled with whatever materials he could find.”

General Reverberi, commander of the Tridentina Division writes, “On January 15, 16, and 17, enemy forces amounting to approximately two regiments supported by numerous batteries of mortars of all caliber, and katyushas, commenced attacking the zone between the Tridentina and Vicenza Division [now deployed in the zone the Julia had previously occupied before moving south].”

Sergeant Rigoni Stern describes several attacks occurring on the lines held by the Vestone Battalion of the Tridentina. Before dawn, the Russians began firing mortars at various strongholds of the battalion. At dawn, the firing ceased as Russian soldiers began crossing the river to the left of Rigone Stern’s stronghold where there was a small island in the middle of the now frozen river. They took cover on the island and subsequently ran toward the riverbank, close to the positions the alpini held. Mortar shells from the alpini hit that section of the riverbank and it seemed that this was the end of their attempt to gain ground.

That same evening the Russians commenced firing with artillery and mortar rounds. This time, as they attacked they slid down in the snow to the riverbank and began running toward the alpini across the river shouting their battle cry, “Ura! Ura!” The alpini managed to fend them off, killing and wounding a good number. When a few Russians reached the barbed wire, the alpini threw the equivalent of a whole case of handgrenades; they failed to explode.

Shortly after, enemy forces began advancing once more. The alpini fired but Sergeant Rigoni Stern realized the Russians were gathering up their wounded. He shouted: “Don’t shoot! They’re gathering their wounded. Don’t shoot!” Surprised the alpini had ceased firing, the Russians quickly gathered their wounded, placed them on sleds and dragged them back to their side of the river. They even removed their dead, except for the ones who had reached the barbed wire.

Following this latest attack, Lieutenant Moscioni collapsed owing to days and nights of no sleep. He had been monitoring the situation intensely, constantly moving from one position to another, checking weapons and taking care of his men. Rigoni Stern writes, “He fell from sheer exhaustion, like a mule.” Moscioni told Rigoni Stern (once they returned to Italy), “It was like being turned into ice…I couldn’t feel my legs any more. I couldn’t feel anything. It was as if I’d only a head and very little of that. It was terrible.” Rigoni Stern took command of the stronghold until another lieutenant could arrive to replace Moscioni.

The Russians began to attack once more, but this time with a different twist. The alpini could hear someone behind the soldiers, “shouting encouragement in Russian” [probably a political commissar]. The sergeant could make out a few words: “country, Russia, Stalin, workers.” The alpini held their fire as the Russians moved out of the woods and slid down to the riverbank. The moment they reached the bottom Stern ordered the alpini to fire, pinning them down. The same Russian voice began shouting again as Russians at the edge of the woods began to retreat back to their trenches, but then a new wave of soldiers appeared and without hesitation began running across the frozen river. It was broad daylight and few survived the barrage of firing from the alpini. A few Russians lay on the snow playing dead, then rose and dashed toward alpini strongholds. They never succeeded. The alpini lost several men during that attack.

General Reverberi noted that the Russians attacked the Vestone Battalion seven times on January 15, leaving “800 dead enemy soldiers in front of their lines.”

Bianco Assunto, who served with the 1st Alpine Regiment of the Cuneense Division, recorded efforts on the part of General Battisti to press for an early withdrawal of the Alpine Corps from the Don. The source of Assunto’s information comes from a meeting held in Cuneo, Italy after the war was over, between Giuseppe Lamberti, commander of the Monte Cervino Battalion, and Major Lequio, at which time Lequio shared the following information with Lamberti.

“General Battisti sent me away from the front at the end of December, having realized following the defeat of the Italian infantry divisions south of the Kalitva River that the Alpine Corps risked encirclement.” Lequio also noted General Battisti tried to persuade General Nasci (commander of the Alpine Corps) and other superior officers to withdraw the Corps around January 10 (a week earlier than the actual date of the withdrawal, January 17) “because that way at least ninety percent [of the alpini] could be saved.”

Battisti could not convince General Nasci. In a last chance effort, Battisti sent Major Lequio to Italy by private plane in an attempt to persuade Prince Umberto of Piedmont to exert his influence on the military authorities in Rome. This effort failed as well.

It is interesting to note that General Battisti makes no mention of these events in his final report, written when he returned from Russia.

Although a withdrawal of Italian troops from the Don was probable by the end of December, and a certainty by January 1943, “nothing was done to organize it except for the pathetic suggestion to the troops to throw together [with whatever means] some little sleds to transport materiel.” Trucks and mules needed for transport of the troops should have transferred in a timely manner from rear zones to the front. Planning to distribute much needed supplies of warm clothing and provisions from warehouses stuffed with food and winter clothing did not occur. There was no careful preparation for a withdrawal route with planned stops and planned distributions from centers located in rear zones.

During this period of rapid escalation of fighting, historian Giorgio Rochat characterizes the leadership of generals Gariboldi and Nasci as “disastrous.” There was a complete “collapse of professionalism and attention to the troops that has never been sufficiently underlined, and it was the myth of the alpini that covered up the failure of their commands.”

On January 10, 1943, orders from central headquarters of German Army Group B arrived, directing the Alpine Corps and the Second Hungarian Army to “hold the lines on the Don up to the last man and the last bullet. No withdrawal from the front was permissible…without orders from the [German] command.” Although these orders were clearcut, General Battisti and his officers remained greatly concerned. Obviously enemy forces could attack the Alpine Corps frontally, but now a possible attack could come from the rear as well. On January 14, Battisti received a call from the headquarters of the Alpine Corps instructing him to prepare for a move of his entire division to another zone. Written orders to this effect would follow shortly.

Lieutenant Egisto Corradi recalled that the alpini didn’t realize the Hungarians deployed to the north of the Alpine Corps were withdrawing from their lines, even though German Army Group B had expressly forbidden a withdrawal. The Hungarians began withdrawing January 16, assuming sole responsibility for their action, following another negative response from the Germans stating that orders from Hitler were not up for discussion. In actuality, even before their official decision to withdraw occurred, various Hungarian formations had pulled back twenty-four hours earlier. Hungarian units directly deployed to the north of the Tridentina Division failed to notify head-quarters of the Tridentina of their intentions. “The confused and disorderly Hungarian withdrawal quickly became a chaotic rout. In the following days, Soviet mobile forces would attack the alpine divisions as they marched west by taking full advantage of the dissolution of the Hungarian sector.”

OPERATION “OSTROGOZHSK-ROSSOSH”

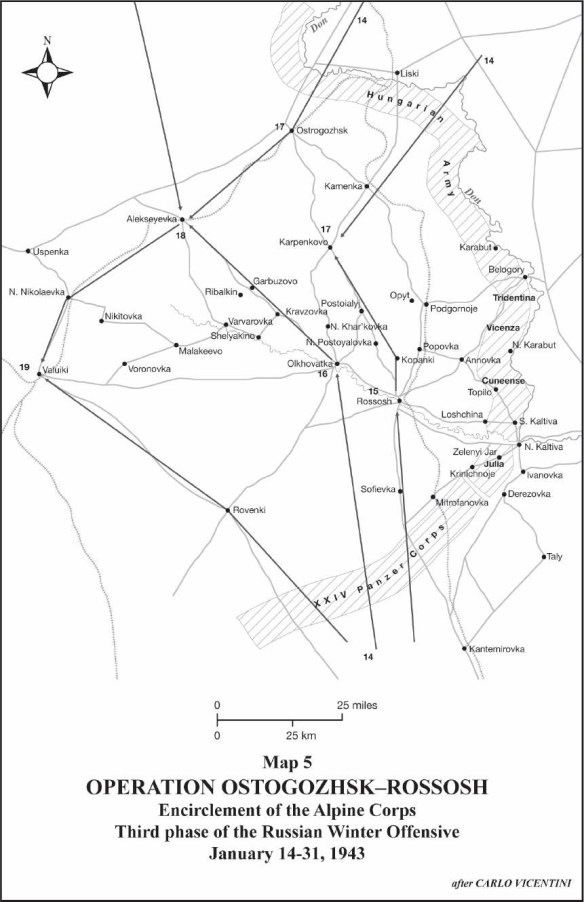

As early as December 20, 1942, the Soviets were mapping plans for their third offensive. The goal was to encircle and destroy the Hungarian, and remaining Italian and German forces on the Don front, and liberate the major railroad lines Liski-Valuiki, and Liski-Kantemirovka, in order to advance toward Kharkov and the Donets Basin.

Operation “Ostrogozhsk-Rossosh” consisted of two main and four secondary attacks. The two main attacks included strikes in the north against the Hungarian Second Army, followed by an advance south toward Alekseevka. From the south, strikes southwest of Kantemirovka, followed by a north and northwest advance toward Alekseevka, would achieve a pincer-like encirclement behind the lines of the Alpine Corps and the Hungarians. Of the four secondary attacks, two were to occur within the pincer formation while two were to take place outside of it.

On January 13/14, the Russians attacked the Hungarian Second Army, to the north of the Alpine Corps, penetrating deep into zones behind their lines. On January 14, the Russians attacked and destroyed units on the German lines held by the XXIV Panzer Corps in and around Mitrofanovka. Russian tanks quickly pushed through those lines, and that same evening they struck the headquarters of the German XXIV Panzer Corps where the commander, General Wendel, lost his life in the ensuing battle.

On January 15, masses of Soviet tanks continued to attack the weakened Hungarian positions in the north, as well as residual units of the XXIV Panzer Corps to the south and southwest of the Alpine Corps. They decimated the German 27th Panzer Division, and the 387th Infantry Division suffered significant losses. The Russians managed to open a large breach in the area held by the Germans and were now able to push north, toward Rossosh, site of the headquarters of the Alpine Corps. In Rossosh, alpini of the Monte Cervino Battalion engaged in a desperate battle against attacking Soviet armored units. All available military personnel in the area, including those with no combat experience, fought in this battle. Approximately twenty Russian tanks roamed the streets of Rossosh, demolishing warehouses, storehouses, and any truck in sight. Using any available means—mines, incendiary bottles, and hand grenades—alpini of the Monte Cervino and auxiliary personnel managed to put five tanks out of commission. German ground-attack aircraft took out another seven or eight. The remaining tanks moved into Italian rear guard zones. That same afternoon, the head-quarters of the Alpine Corps transferred from Rossosh to Podgornoje. Military hospitals were evacuated, as well as personnel from various auxiliary services. By noon of January 16, the Russians had occupied Rossosh.

On the morning of January 16, a Russian plane dropped leaflets near the lines where the Julia Division was still fighting. On one side of a very small leaflet of yellow paper (written in Italian) it read, “Italian soldiers! You are surrounded.” On the other side, written in Italian at the top and Russian at the bottom it read, “Lasciapassare” (pass or permit); “To all officers and soldiers who surrender we guarantee life, good treatment and your return to your homeland as soon as the war is over.” The leaflet was signed, “Command of the Red Army of the Don.”

A second leaflet, written in Italian on light blue paper with more text, guaranteed the same rights to prisoners as that written on the yellow paper. In addition, the text advised Italian soldiers to “agree with your trusted companions to act together so you can avoid surveillance by [your] officers and their spies.” It also advised soldiers to distance themselves from their commanders during a withdrawal, to fake a limp, and remain hidden in an izba until Russian soldiers arrived. “During a Russian attack, raise your hands. If there is a traitor in your midst, tie him up or better yet, kill him. Don’t in any case take off your uniform. The international directive requests this. For Russians the rules of war are sacred. Every pass is valid for as many who surrender. If you don’t have a pass, learn to shout these words loudly, ‘Russ sdaius!’ (‘I surrender’).”

On January 15, the ARMIR command requested permission from German Army Group B to withdraw the Alpine Corps along with the Hungarian Second Army, which was already withdrawing at that point. Hitler refused to allow the Alpine Corps to withdraw, but he permitted some troops of the German XXIV Panzer Corps to withdraw north of the Kalitva River.

General Karl Eibl, who had assumed command of the XXIV Panzer Corps, ordered all remaining German troops operating with the Julia Division to withdraw. Vicentini writes, “The design of the German command was evident, namely to forge ahead of the Julia Division in the by now inevitable withdrawal, leaving the Julia Division to form their rearguard, and at the same time having a clear road ahead in order to move rapidly ahead of the Italians. This action weakened the already gravely tested Julia, but most of all it left its flank, south of Krinichoje, completely exposed.”

As German troops to the south and southwest of the Julia Division began to withdraw, alpini of the Julia had to quickly extend and rearrange their defensive positions. ARMIR headquarters informed the command of German Army Group B that it was imperative to authorize the withdrawal of the Julia Division, as well as the other alpine divisions still positioned on the Don, so as to prevent their encirclement.

Despite tight German control of the Alpine Corps, General Nasci and his officers had actually mapped out a plan for a possible with-drawal. It included a specific itinerary the divisions were to follow once a retreat commenced. On January 15, General Battisti received written orders for the withdrawal of the Alpine Corps from the Don. These orders opened with the following statement: “Unfavorable events in other parts of the front constrain the Alpine Corps to withdraw in order to prevent encirclement.” The three Alpine divisions (including the Vicenza Division, incorporated into the Alpine Corps since November 20), the German XXIV Panzer Corps, and all troops and service units posted in the Rossosh zone were to move toward the “alignment Valuiki–Rovenki as quickly and efficiently as possible.” Furthermore, the orders stated that once the troops so deployed, a new defensive line would be drawn, fortified by German troops arriving in that zone.

The orders included specific routes for the divisions to follow. However, as General Battisti notes, operational orders for the withdrawal were developed during the night of January 15, before columns of Russian tanks and troops had reached and occupied Rossosh, and two days before the Russians captured the strongpoints of the proposed line of defense: Valuiki–Rovenki.

In actuality, the overall situation on the ground had changed radically even before the withdrawal was to begin. In order to realize necessary deviations and to change course from the original plans for the withdrawal, there should have been close and constant communication between the Alpine divisions and their corps headquarters, as well as communication with the superior commands, namely the Germans. In fact, in the case of the Cuneense Division, communication between that division and the headquarters of the Alpine Corps ceased on the morning of January 15 (on January 20 a very brief radio connection was reestablished for only a short period).

Already on January 15, General Nasci had ordered alpine units on the front lines to transport heavy equipment from supply depots and camp hospitals to Popovka and Podgornoje. Soldiers in charge of horses and mules located behind the lines received orders to move the animals to the front in order to transport these heavy loads. Some units failed to reach the front with quadrupeds because of Russian attacks. Consequently many alpine units, especially those of the 2nd Regiment of the Cuneense Division, began their withdrawal with approximately twenty mules per company. This of course had grave consequences for the mobility and survival of men in those units.

The following order, received by General Nasci at 0600 on January 17, clearly demonstrates the control the Germans had over the destiny of the Alpine Corps: “TO LEAVE THE DON LINE WITHOUT ORDERS FROM ARMY [Group B] IS ABSOLUTELY FORBIDDEN. I WILL MAKE YOU PERSONALLY RESPONSIBLE TO EXECUTE THIS [ORDER].”

Although enemy forces had encircled the Alpine Corps, General Nasci reported that the Corps was still in good shape, even though it remained under strict control by the Germans.

At 1000 of the same day, Nasci received orders from ARMIR head-quarters to withdraw from the Don, and to maintain close contact with the Hungarian Second Army deployed to the north. The General was also informed that Russian tanks had reached Postoialyj, which confirmed the fact that the Corps was completely encircled. In addition, German Army Group B placed the XXIV Panzer Corps under Nasci’s command. It was now equipped with only four tanks, two self-pro-pelled guns, and scant artillery including a battery of rocket launchers. Nasci noted that the 385th and 387th divisions of the Panzer Corps were “reduced to shreds,” and their fighting ability could be considered “negligible.”

At 1100, General Nasci received another message from the head quarters of the ARMIR, authorizing the withdrawal of the Alpine Corps from the Don. The message ended with the following: “God be with you.” The message also stated that the withdrawing Alpine Corps should maintain close contact with the Hungarian Second Army. Of course, that was impossible. By now, Russian forces had overrun the Hungarians and already there were reports of disorganized units of Hungarians near Opyt, northwest of Podgornoje. That same day, General Nasci received news that the Russians had occupied Pos-toialyj and Karpenkovo. The encirclement of the Alpine Corps was now complete.