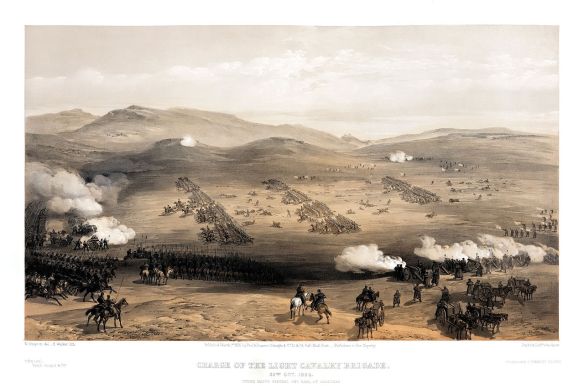

The Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava by William Simpson (1855), illustrating the Light Brigade’s charge into the “Valley of Death” from the Russian perspective.

The Timeline of the Charge taken from Forgotten Heroes: The Charge of the Light Brigade (2007).

To those coolly sitting on their horses with Lord Raglan on the Sapouné Heights, the incident must at first have appeared to be an instance of that insolent indifference to danger which characterized many a British military operation in the nineteenth century. Later, it must have seemed more like culpable inactivity, and indeed it was only comprehensible when the contours of the ground beneath these onlookers were properly appreciated. A substantial body of Russian cavalry advancing to attack the Highlanders had seemed to pass within a few hundred yards of the British cavalry, now stationed where Raglan had ordered them, to the left of the second line of Redoubts. Yet although the Russian cavalry passed so close to Lucan’s division, the two formations could not see each other, were not in fact aware of each other’s proximity, simply because of the high ground between them, screening each from the other’s view. Yet to Raglan and his staff looking down upon them, this mutual unawareness was not apparent. When the Russian cavalry then set about attacking the 93rd Highlanders, ‘the slender red line’ proved more than a match for the enemy squadrons. Three times the Russians came at then; three times they were repulsed by the disciplined steadiness and accurate fire-power of the 93rd. At one point Campbell had to quell his men’s eagerness to charge with some fitting oath, but they had done the trick. The enemy withdrew.

Yet these half-dozen or so squadrons were but the vanguard of a much larger body of Russian cavalry which had followed them across the Causeway Heights. Perceiving this further threat, Raglan had issued his second order – indeed, had done so before the Highlanders’ gallant action had been fought – and this order, ‘Eight squadrons of Heavy Dragoons to be detached towards Balaklava to support the Turks who are wavering,’ arrived too late to be executed in the way that Raglan had intended. In command of these Dragoon squadrons was Brigadier-General Scarlett, whose face was as red as his tunic, a brave and competent cavalryman who had won the respect and affection of his men for his unassuming and good-natured ways. He was now about to bring off ‘one of the great feats of cavalry against cavalry in the history of Europe’. As he led his eight squadrons, two each from 5th Dragoon Guards, Scots Greys, Inniskillings and 4th Dragoon Guards, towards Balaklava, with the Causeway Heights on their left, he observed on the slopes of these heights a huge mass of Russian horsemen. There were three or four thousand of them. Yet Scarlett with his mere 500 or so Dragoons was quite undismayed and coolly ordered his squadrons to wheel into line. It was at this point that Lucan arrived on the scene and ordered Scarlett to do what he was about to do anyway – charge the enemy. It was fortunate that the Russian cavalry came to a halt with the intention of throwing out two wings on their flanks in order to engulf and overwhelm Scarlett’s force. Thereupon Scarlett ordered his trumpeter to sound the charge.

Although the Light Brigade’s action at Balaklava is more renowned, it was the Heavy Brigade’s charge which was truly remarkable as a feat of arms. In spite of the appalling disparity of numbers, the British cavalry enjoyed one great advantage. The Russian hordes were stationary, and it is an absolute maxim that cavalry should never be halted when receiving a charge but should be in motion. By remaining stationary, the Russians would sustain far more devastating a shock. For those surveying from the heights, what now transpired was breathtaking. Scarlett and his first line of three squadrons seemed to be positively swallowed up by the mass of grey-coated Russian cavalry, and although this enemy mass heaved and swayed, it did not break. Indeed, their two wings, in motion again now, began to wheel inwards to enclose and crush the three squadrons. But now Scarlett’s second line took a hand in the game. The second squadrons of the Inniskillings and 5th Dragoon Guards flung themselves wildly into the fray on the left, while the Royals, who had not received orders to do so, but rightly acted with timely initiative, charged in on the right. There was further heaving and swaying by the Russians, but no sign yet of breaking.

No such initiative as that of the Royals was displayed by Lord Cardigan, who was about to be presented with the chance of a lifetime. He and his Brigade were a mere few hundred yards from the flank of the Russian cavalry, observing the action, most of them consumed with impatience, yet no thought of joining in the fray even occurred to Cardigan. The best he could do was to declare that ‘These damned Heavies will have the laugh of us this day.’ Any commander possessed of the real cavalry spirit would have been longing for the moment to arrive when his intervention would have been decisive. And this moment was about to come. Despite his dislike and contempt for his superior commander, Lord Lucan, Cardigan took refuge in his contention that he had been ordered to remain in position and to defend it against any enemy advance. It would have been far more in keeping with his custom to have ignored Lucan’s order. Indeed, Lucan himself maintained that his instructions had included a positive direction that the Light Brigade was to attack ‘anything and everything that shall come within reach of you’. There could be no gainsaying that the Russian cavalry, already reeling from the Heavy Brigade’s assault, came within this category.

Action by the Light Brigade was about to become even more opportune and necessary, for it now became apparent that the Russian cavalry mass was recoiling, being pushed back, swaying uphill. Now was the moment for the coup de grâce and it was delivered by the 4th Dragoon Guards, who had been held in reserve and were now ordered to charge by Lucan. Crashing into the Russian right and charging head on, the regiment went right through the enemy force. ‘The great Russian mass,’ wrote Cecil Woodham-Smith, ‘swayed, rocked, gave a gigantic heave, broke, and, disintegrating it seemed in a moment, fled.’ If ever there was a moment for pursuit to finish the thing off and write finis to the battle of Balaklava, it was now. If only Cardigan had seized this moment and charged then, the victory would have been complete and the Russian cavalry would not have been allowed to escape. But Cardigan was not a man to act without specific orders. Initiative, except in designing bizarre uniforms or ogling pretty women, was foreign to his nature. What Cardigan could not or would not see, others did, and urged him to act. Captain Morris, commanding the 17th Lancers, urgently pressed his brigade commander: ‘My lord,’ he said, ‘it is our positive duty to follow up this advantage.’ Cardigan insisted that they must remain put. Morris further implored him to allow his own regiment to charge the enemy who were in such disorder. Cardigan was adamant. Furious and frustrated, Morris appealed to his fellow officers: ‘Gentlemen, you are witnesses of my request.’ Cardigan’s refusal to act was even more reprehensible than Grouchy’s inactivity at Waterloo for he could at least see what was going on.

The moment passed, and the Russian cavalry, unmolested further and complete with their artillery, were allowed to establish themselves at the eastern end of the North Valley, guns unlimbered and ready for action. They would not have long to wait. Yet if the Charge of the Light Brigade had been enacted during the Russian disorder and flight, no such controlled movement would have been possible by the enemy. In short, the Russians would have been unable to redeploy at the eastern end of the North Valley, and thus there would have been no such objective for Raglan to concern himself with and about whose capture he was now to issue further wholly confusing orders. We may perhaps conclude this particular speculation by observing that had the Light Brigade charged when it should have done, the two actions of the Heavy and Light Brigades would have become one, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson would have had to confine himself to one poem rather than two.

Lord Raglan now set about the business of making confusion worse confounded. His third order was given when, as a result of the Heavy Brigade’s action, the Russians recrossed the Causeway Heights and were to the north of them. Raglan determined to recapture the Redoubts, the Causeway Heights and the Woronzoff Road. To take and hold ground would, of course, demand infantry. The 1st Division was at hand, but the 4th Division, under command of a disgruntled, almost insubordinate Sir George Cathcart, was taking its time to get forward. Not wishing to lose his chance, Raglan conceived the idea of recovering the Heights with cavalry, who would then hand over to the infantry divisions. But Raglan’s third order was once more a masterpiece of ambiguity. Moreover, the version of it retained by him differed from that which reached Lucan. What Raglan had intended was that the cavalry should advance at once, recapture the Redoubts and control the Heights until the infantry came up. But the order which reached Lucan implied that he should wait until the infantry were there to support him before advancing. In other words Lucan’s reading of the order – not to advance until supported by infantry – was the exact opposite of what Raglan intended. It was therefore with mounting impatience that Raglan gazed down at the action which Lucan did take – to mount the Cavalry Division, positioning the Light Brigade at the western end of the North Valley, while the Heavy Brigade was drawn up behind them on Woronzoff Road. Thus deployed, Lucan waited for the infantry.

Raglan, in his certainty that an advance by the cavalry would oblige the enemy to withdraw from the Redoubts, could not understand why Lucan made no move, and when he saw that parties of Russian artillerymen were preparing to take their guns away from the Redoubts, his agitation knew no bounds. It was then that Raglan sent out the fatally misunderstood fourth and last order to Lucan. It read: ‘Lord Raglan wishes the Cavalry to advance rapidly to the front – follow the enemy and try to prevent the enemy carrying away the guns. Troop Horse Artillery may accompany. French cavalry is on your left. Immediate.’ This order had been written out by General Airey from Raglan’s instructions. We have seen that lack of precision in the third order resulted in its not being carried out. If it had been clear and executed as intended by Lucan, the fourth order would never have been needed. Yet here with this fourth order we see again that a precise word or two substituted for an imprecise phrase would have removed all ambiguity. What ‘to the front’ means to one man is very different from what it means to another. Had Raglan so phrased the order that it clearly complemented his previous one, the one relating specifically to the Causeway Heights, as he meant it to, how differently Lucan would have read it. Had it said, ‘Cavalry to advance to the Causeway Heights to prevent enemy carrying away the guns from the Redoubts,’ Lucan would have been in no doubt as to what his Commander-in-Chief wanted.

This is the first great If which could have prevented the Noble Six Hundred from riding into the Valley of Death. The second is that if only any aide-de-camp other than Captain Nolan of the 15th Hussars had carried the order to Lucan, there might have been some chance of Lucan’s realizing what Raglan actually intended. As it was, Nolan, who had endured agonies of humiliation and frustration at the Light Brigade’s inexplicable inactivity when so splendid and classic an opportunity following the Heavy Brigade’s charge had presented itself, was given the task. Moreover, Raglan aggravated both the imprecision of his order and the furious impetuosity of Captain Nolan by calling out to him as he rode off, ‘Tell Lord Lucan the cavalry is to attack at once.’

To Lord Lucan this new written order, which he regarded as quite unrelated to the previous one, was not merely obscure, it was crazy. The only guns that he could see were those at the eastern end of the North Valley – to his front. For cavalry to attack batteries of guns frontally and alone was to contravene every tactical principle and to invite destruction. As Lucan read and re-read the order with mounting consternation, Nolan, almost beside himself at Lucan’s apparent reluctance to take immediate and decisive action, repeated in tones of arrogant contempt the Commander-in-Chief’s urgent postscript that the Cavalry should attack at once. Small wonder that Lucan should have burst out angrily, ‘Attack, sir? Attack what? What guns, sir? Where and what to do?’ It was then that Nolan threw away the last chance of the operation going according to plan. With a furious gesture but, alas, one fatally lacking in proper direction, he pointed, or appeared to point, at the very guns that Lucan could see, those at the end of the North Valley, accompanying his gesture with words full of insolence and empty of precision: ‘There, my lord, is your enemy, there are your guns!’

Here we may pause for an instant and insert another If. If only, at that very last moment, Nolan had curbed his frantic impatience and calmly explained to Lucan that the guns in question were those on the Redoubts and that therefore the Light Brigade must advance to the Causeway Heights, all might yet have gone well. But after this ill-tempered exchange, Nolan rode over to Captain Morris, 17th Lancers, and asked if he might ride with the Regiment. Morris agreed. Meanwhile, Lucan had passed on the order to Lord Cardigan. Even Cardigan felt obliged to point out that the valley was commanded by guns not only to the front, but to the right and left as well. Lucan acknowledged his objection, but insisted that it was the Commander-in-Chief’s wish and that there was no choice but to obey.

Thus the position when Cardigan deployed his brigade in readiness to advance was that the Russians occupied the Fedioukine Heights with horse, foot and guns, and the Causeway Heights including the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Redoubts with infantry and guns. At the head, that is, the eastern end, of North Valley were twelve Russian guns and behind them their main body of cavalry. About a mile and a half away, at the western end of the valley, was the Light Brigade. By this time the British infantry had come up, the 1st Division occupying ground held by the 93rd Highlanders, while the 4th Division was in the area of the 4th Redoubt. After receiving his orders from Lucan, Cardigan rode over to speak to Colonel Lord George Paget, commanding the 4th Light Dragoons, who was to command the second line of the brigade. Cardigan told Paget that he would expect his best support. Paget had been enjoying a ‘remarkably good’ cigar while Nolan and Lucan had their angry exchange, and when he heard Colonel Shewell of the 8th Hussars reprimanding his men for smoking their pipes – in Shewell’s words, ‘disgracing the Regiment by smoking in the presence of the enemy’ – he could not but wonder whether he was disgracing his regiment with his cigar. ‘Am I to set this bad example?’ he asked himself. A good cigar, however, was no ‘common article in those days’ and he determined to keep it. The 4th Light Dragoons had a reputation to maintain. They were known as ‘Paget’s Irregular Horse’, and the cigar lasted until the charge was over.

It might be supposed that Lucan had already contributed enough to the day’s work, but even now he interfered further. Cardigan had placed three regiments, the 13th Light Dragoons, 17th Lancers and 11th Hussars, in the front line, while the second line had the 8th Hussars and 4th Light Dragoons. Lucan ordered Colonel Douglas, commanding 11th Hussars, Cardigan’s own regiment, to drop back to a position supporting the front line. As the charge proceeded Paget, conscious of Cardigan’s insistence on his best support, had brought the 4th Light Dragoons up to the left of the 11th Hussars, thus forming a new second line, with the 8th Hussars to the right rear. ‘Walk march. Trot:’ Cardigan gave the order. His trumpeter sounded ‘March’. The charge was on. Captain Portal, 4th Light Dragoons, recalled later that they had ridden only a quarter of a mile, galloping now, when the most fearful fire opened on them from both sides, dealing death and destruction in the ranks. They kept going, did their work among the enemy guns, which with support – of which there was none – they could have brought back with them, and then retired in good order, still at the gallop and again through murderous crossfire. Neither Portal nor anyone else seeing what had to be done thought that those still alive after the charge would ever get back.

One of the 8th Hussars, Lieutenant Calthorpe, who was serving on the staff and did not take part in the charge, observed it all, his own regiment and the others thundering along the valley at an awful pace, unchecked by the fearful slaughter, disregarding all but their objective, rendering havoc amongst the enemy’s artillery. This was the time, Calthorpe recorded, when the brigade commander should have rallied his men, gripped the situation and given the necessary orders. But according to Calthorpe, Cardigan’s horse took fright, wheeled round and galloped back down the valley. Calthorpe was mistaken here. Neither Cardigan nor his charger had taken fright. Indeed, perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the whole affair was Cardigan’s absolute indifference to the hazards of the charge or the fate of his brigade once it had charged. He evaded some threatening Cossacks by galloping back through the enemy guns, and judging his duty now done, calmly rode back down the valley.

It was left to the combined efforts of Paget and Shewell to take control and salvage what was left of the Light Brigade. As the Brigade charged home, the leading lines of the 13th Light Dragoons and 17th Lancers suffered terrible casualties as the guns in front of them opened fire. Those surviving, about fifty, galloped through the guns, sabres and lances at work, and on to rout some Russian Hussars, until they were checked by numerous Cossacks. Then the 11th Hussars came right through the guns in pursuit of fleeing enemy Lancers. Paget was leading the 4th Light Dragoons at full gallop on to the enemy gunners, and to their right the 8th Hussars under the iron hand of Colonel Shewell went through the battery and pulled up on the far side. Now the survivors faced a double threat, from a huge body of enemy cavalry in front and from six squadrons of Russian Lancers who had descended from the Fedioukine Heights, endangering their withdrawal. In the absence of Cardigan, Paget rallied the 4th Light Dragoons and 11th Hussars, charged towards the enemy Lancers and brushed past them. Shewell did the same with seventy troopers, and the retreat, worse by far than the charge itself, began. Mrs Duberley, wife of the 8th Hussar paymaster, observing pitiful groups of men making their way back down the valley and realizing who they were, exclaimed: ‘Good God! It is the Light Brigade.’

One of Paget’s comments on the bearing of riderless horses during the charge itself is revealing and shows what terror these noble creatures could feel without the reassuring presence of their riders:

They made dashes at me, some advancing with me a considerable distance . . . cringing in on me, and positively squeezing me, as the round shot came bounding by them, tearing up the earth under their noses . . . I remarked their eyes, betokening as keen a sense of the perils around them as we human beings experienced . . . The bearing of the horse I was riding, in contrast to these, was remarkable. He had been struck, but showed no signs of fear . . . And so, on we went through this scene of carnage, wondering each moment which would be our last.

‘Then they rode back, but not Not the six hundred’, wrote Tennyson. Someone had blundered all right, but who was it? Was Lord Raglan justified in accusing Lord Lucan, ‘You have lost the Light Brigade’? When things go right in a battle, there is no shortage of those claiming credit for it. When things go awry, the number who step forward as candiates for recognition tends to be smaller. We may recall that during the battle of Balaklava, Raglan issued four orders. None of them was precise. None of them was properly understood. None of them was executed in the way that had been intended. The whole affair may be regarded as a series of unfortunate chances, preceded, however, by one golden chance, one unique opportunity, one classic moment for decision, which if taken, seized and exploited would have ended the battle on a note of triumph for the British cavalry in particular and the British army in general. This moment was, of course, when the Russian cavalry was fleeing from the Heavy Brigade’s charge, and the Light Brigade failed to turn the dismayed enemy flight into absolute rout. Then, with the aid of the advancing infantry divisions, Raglan could have inflicted such a defeat on the Russian forces at Balaklava that they might have lost stomach for a continued campaign there and then. Sebastopol would have fallen and the Crimean War would have been over.

But given that this chance was lost, we must remember the other less welcome chances – the chance position of Raglan from which he and his staff were quite unable to appreciate what Lucan could or could not see; the chance of his totally inadequate orders, which did not define either line of advance or object of attack; the further chance of Raglan’s not making it clear that the cavalry was to move at once, not to wait for the infantry to arrive; and the chance of choosing Nolan of all men to deliver both the written order and the further urging of Lucan to attack at once. If all or any of these blunders had not been committed, the Light Brigade would have prevented the guns from being removed from the Redoubts and the battle could have proceeded with the infantry’s arrival. It was not only Lucan who had lost the Light Brigade, although he must bear heavy responsibility. Between them all – Raglan, Airey, Lucan, Cardigan, Nolan – they saw to it that chance governed all and that chaos umpired the whole sorry business.

It is to the Noble Six Hundred that we must give the accolade. Riding back down the valley at the rear of what was left of the 4th Light Dragoons and the 11th Hussars, Paget noted the last mile strewn with dead and dying, all of them friends, some of them limping or crawling back, horses in agony, struggling to rise, only to flounder again on their mutilated riders. It had been, in Cardigan’s words, ‘a mad-brained trick’, but all the regiments of the Light Brigade had covered themselves with glory. Even in ‘the jaws of death’ discipline had been superb in completing the business of ‘sabring the gunners there’. Some of those who rode back even told Cardigan that they were ready to go again.

Honour the Light Brigade! Magnificent, but not war. This was a French observer’s judgement. The French were reliable and competent Allies in 1854.