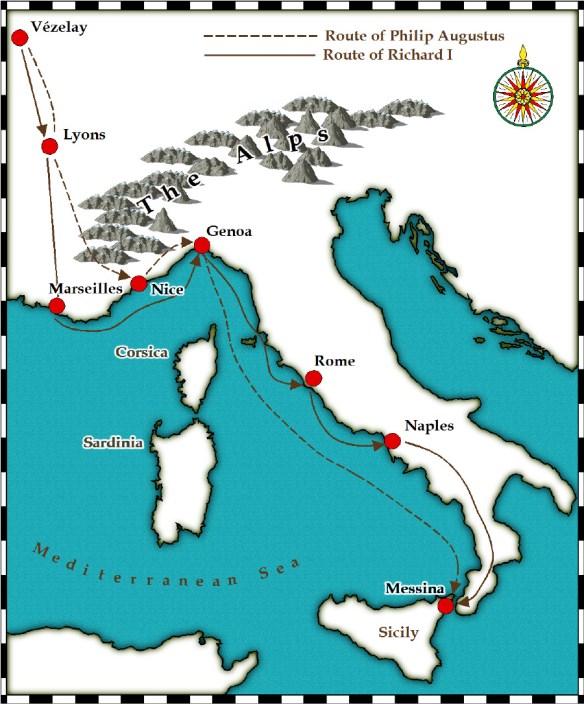

Richard and Philip initially set off with the goal of reaching Lyon. However, their traveling partnership did not fare well for long. Upon reaching Lyon, the kings and their party had to cross the Rhone River, and disaster struck. The flimsy wooden bridge they were using to cross the river collapsed as some of their retinues, with heavy wagons full of supplies, marched over. A few people were killed, some were injured, and others were stuck, unable to cross until they located enough boats to create a temporary bridge. After this misfortune, Richard and Philip decided to journey separately. Philip would travel by sea, departing from Genoa. Richard continued the overland trek, heading toward Marseille. The two kings agreed to meet again in Sicily, at the city of Messina.

Richard’s journey to Marseille was not in itself problematic, but he ran into unexpected difficulties once he arrived there on July 31. He had intended to meet his fleet there, but they had not yet appeared. Richard had no way of knowing that his men had been delayed, sidetracked by helping the king of Portugal fight against the Moors. King Richard waited, but soon a week had gone by with no sign of the fleet. He decided he could wait no longer. The king found ships to lease in Marseille and once again set out on his way. He traveled along the coast of Italy, stopping in Genoa, Portofino, Pisa, and Piombino. At last, in Rome, after making several complaints to the pope, Richard left his ships for horses and rode toward Naples. He arrived there on August 28, after almost two months of travel. From Naples, it was not far to Salerno, where Richard finally heard word of his missing fleet, which was on its way to Messina. The king, pleased with the news, continued his slow journey to rejoin his men.

Richard arrived in Messina at last on September 22. The following day, he made a grand and impressive entrance into the city, complete with blaring trumpets and clanging swords. Richard found Philip already waiting for him in the city. Soon after Richard’s arrival, everyone was impressed by the show of affection between the two kings. The ruler of Sicily, King Tancred, also treated the kings with exceptional deference and courtesy. Richard’s sister Joan had been the wife of William, the previous ruler of Sicily, and King Tancred offered to allow Joan to join Richard on the crusade. Richard, however, wanted a bit more—he asked Tancred to turn over Joan’s dowry as well. Tancred refused. Though Richard let the matter rest for the time being, three kings and their armies could not lodge in the same city for long without the slow increase of tense undercurrents.

The tension broke into violence just a few days later, on October 3. Richard had commandeered a small monastery in which he stored his supplies, and the people of Messina were outraged. He had also left troops at the castle of Bagnara, just across the straight on the mainland of Italy, where his sister Joan was staying. Between these two actions, however, it looked possible to some that Richard intended to conquer Sicily. Fighting broke out in the city between Richard’s men and the Sicilian citizens. Though at first the clashes were small, the violence quickly spread through Messina. Richard, not expecting the sudden turn of events, tried to put an end to the fighting by riding out and commanding his men to move back, away from the walls. His attempts were unsuccessful. He immediately changed tactics, meeting with King Philip and King Tancred to re-establish peace. This peace lasted less than a day before the fighting started once more.

Richard was enraged at the townsmen who dared to attack his army, and he quickly came up with a new and surprising plan. He would hold Messina itself for ransom until King Tancred met Richard’s demands. Here Richard showed his tactical strength. His men, drawn up in position to attack the city, held their fire until the defenders’ arrows were spent. They then returned a volley of arrows on the city walls, causing the defenders to dive for cover. Under the hail of arrows, Richard’s men beat down the gates with a battering ram. Richard and his knights charged inside, speedily seizing key locations and taking hostages from prominent families; at the same time, others of Richard’s men were busy setting fire to all of Tancred’s ships. Using the hostages as bargaining chips, Richard maneuvered his way into control of the city, and from there worked out a deal with Tancred. The Sicilian king agreed to give Richard the additional money he wanted for Joan’s dowry, Richard returned the city to the townspeople, and the two kings finally came to an agreement for peace.

Through the winter the armies camped in tents around the city while Richard and other noblemen stayed inside. Despite a brawl between different camps of sailors around Christmas, the established peace held. For Richard, the most significant event around this time was his decision to make a confession to the Church. In private, to important church leaders, Richard presented himself in a position of humility, barefoot and carrying thorns tied as scourges. What exactly he confessed is uncertain. Some historians have speculated that Richard could have been a homosexual—a serious offense in the eyes of the Church and medieval law—and at this time he may have renounced and asked to do penance for these sexual preferences. Whatever Richard revealed, he was declared absolved.

As the new year began, fresh news arrived in Richard’s world. From England came word that John, whom Richard had allowed to return to the country, was causing trouble with the justiciars Richard had left in control. In Richard’s more immediate proximity, his mother was attempting to come by land to meet him. With Eleanor came a young woman named Berengaria, the daughter of the king of Navarre, a province in the north of Spain. King Tancred, however, would not let Eleanor and Berengaria set sail from Naples to Messina. Tancred and Philip were aligned at this point, and Philip’s sister Alice had long been betrothed to Richard as a part of political maneuvering. Philip suspected, correctly, that Richard had no intention of marrying Alice and planned to marry Berengaria instead. The three kings traveled to Taormina to negotiate. Along the way, Tancred, who still wanted Richard’s support in other serious mattered involving his own claim to the Sicilian throne, produced letters to show that Philip was hatching plans against Richard. Whether the evidence was real or not, Richard was convinced. Tensions rose between the three kings, and Richard turned around and headed back to Messina.

At last, at the end of March, Count Philip of Flanders mediated a deal between the kings. Territory and money changed hands. Richard was released from his obligation to marry Alice. The Treaty of Messina also dictated that the French and English kings would share the spoils of the crusade, and it became the document that defined the relationship between their kingdoms during the remainder of Richard’s reign.

On April 10, with conflict and negotiation behind them, the kings were ready for their armies and ships to depart. After stops in Crete and Rhodes, Richard’s fleet approached Cyprus. The island had been taken by an unpopular ruler, Isaac Comnenus. When a few of Richard’s ships were wrecked in a storm, Isaac imprisoned the surviving men from the ships. Richard arrived on the island on May 6, and negotiations soon escalated into conflict. Richard was victorious and demanded Isaac’s support for the crusade.

While in Cyprus, Richard also paused his journey for his wedding to Berengaria and her coronation, a lengthy celebration. Despite this event, Richard’s dealing with Isaac was not quite over. The Cypriot ruler stole out of town shortly before signing his agreement with Richard. Richard took time to hunt him down, despite the arrival of urgent messages encouraging the English king to hurry to the Holy Land. After an unsuccessful battle from which Isaac escaped, Richard captured two of Isaac’s key castles. He then made a discovery: in one of the castles, he had unknowingly trapped Isaac’s daughter. Because of this, finally, at the end of May, the Cypriot ruler surrendered. Richard received abundant funding from the Cypriots and had gained a valuable harbor. At last, he was ready to sail on toward the Holy Land.