Major General Alan Jones 106th Division

The 106th Infantry Division, Alan Jones’s Golden Lions, had experienced a frustrating first day of combat on 16 December. None of their training back in the USA or England had prepared them for the freezing conditions of the Christmas-card-pretty Schnee Eifel, with its narrow, winding roads, and mist-shrouded, snowy hills, interspersed with dense forests of fir and pine. Neither had they expected a total lack of situational awareness. The hostile bombardment had cleverly hit their artillery positions first, then headquarters, finally infantry units. Confusion reigned because the lines were out; even those who got through did not get any orders: nobody knew anything.

Pete House served the 105mm guns of Battery ‘A’ of the division’s 590th Field Artillery Battalion, based in Oberlascheid, a tiny settlement midway on the Bleialf to Auw ‘Skyline Drive’, high on the Schnee Eifel. In 1994 he told me how his unit was hit hard on the 16th: ‘The German army knew the location of every rock and stream and could drop a shell wherever they wanted with great precision,’ he observed. ‘Each time we moved into position and fired our guns the Germans quickly located us and would fire back. We soon learned when orders for a fire mission came in to have everything packed and our trucks brought right up to the guns. As soon as the firing was over it was “move like hell” because immediate German counter-battery fire would be incoming.’

Sergeant John P. Kline, a former ASTP scholar, had been brought up in Indiana where his best subjects at high school were ‘basketball and girls’. He remembered his first German artillery barrage: ‘It was unbelievable in its magnitude. It seemed that every square yard of ground was being covered. The initial barrage slackened after forty-five minutes or an hour. The woods were raked throughout the day by a constant barrage of small arms and artillery fire. We were pinned down in the edge of the woods and could not move. I found some protection in a small trench, by a tree, as the shelling started. I heard a piece of metal hit the ground. It was a large jagged, hot, smoking piece of shrapnel, about eighteen inches long and four inches wide. It landed a foot or two from my head. After it cooled off I reached out and picked it up.’

‘Incoming mail’, as veterans referred to hostile artillery fire, turns any greenhorn into a veteran. It was – and remains – the first test of a soldier in battle, for the violence is random. Much of a GI’s ability to survive rested on skill and professionalism, but enduring shellfire was a mental test for those who could ‘take it’ and those could not. It was an exam that couldn’t be prepared for in advance: a soldier only knew how he would react when the storm of steel started to land around him. Some prayed; others were wonderstruck, describing the ground reverberating like Jell-O; still others ran around screaming in terror. John A. Swett in Company ‘H’ of the 423rd remembered a German victim of shellfire: ‘He appeared to be very young, perhaps fourteen or fifteen years old. He had a deep vertical slice in his back, perhaps twelve inches long and down to his rib cage. He had been given a cigarette and seemed to be unconcerned about his condition. Probably he was in a state of shock.’ Some GIs shot themselves in the hand or foot, to be swiftly evacuated out of the battle zone. Corporal Hal Richard Taylor in the 423rd Regiment’s Anti-Tank Company saw a fellow GI reacting to fire for the first time ‘crouched near the floor. He had dropped his rifle and had his arms crossed over his head’ – inside a German bunker where he was perfectly safe.

In the nearby 99th Division, William Bray recalled the post-shelling reaction of a pair of GIs ‘who crouched for two days whimpering with their knees drawn up and blankets over their head. They had gone to the toilet in their pants’, but he did not condemn them for the ‘horror of that artillery would cause a breakdown in the best of us’. John A. Swett remembered seeing ‘a tall lean fellow digging himself a foxhole. When he finished his hole he got into it and nothing could prise him loose. He was still digging for more than an hour afterwards.’ Kline’s observations of those first moments under fire continued: ‘At one point, as I looked to the right along the edge of the woods, I saw six or eight ground bursts. They hit in a small area along the tree line where several soldiers were trying to find protection. One of those men was hurled through the air and his body was wrapped around a tree trunk several feet off the ground. There were continuous cries from the wounded screaming for Medics.’

Perhaps the fact that the Golden Lions had the youngest average age of any division in the US Army decreased their resilience. Some were so young, green to combat and ill trained, they knew that they didn’t stand a chance. Pete House told me of some new arrivals at his POW camp in fresh-looking uniforms. He asked them for their division and was astonished to find they didn’t know. After basic training in the United States followed by ten weeks of training in one of the dreary redeployment camps (one of the infamous and much-hated ‘repo-depos’), they’d been dropped off at night next to their foxholes by a sergeant they’d never seen before or since, and soon after had been captured. Such a lack of unit cohesion increased a sense of isolation and disinclination to do anything, especially under fire. Some soldiers (British, German, as well as GIs) have admitted to me in interviews that they did not know the names of any towns or villages they passed through (‘all looked the same after shelling’), and barely knew the names of their officers.

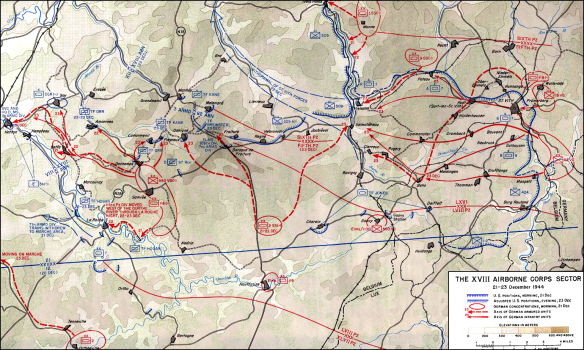

Many of the newly conscripted Volksgrenadiers were as poorly trained, but in the first flush of victory their high morale spurred them on, as one wrote home on 24 December: ‘Yes, you are surprised that we are again in Belgium, but we advance every day. Well, what does father say to that? I had a conversation with him last time about the war and he was not very convinced then that we should be able to do such a thing. Everyone is enthusiastic as never before.’ Late in the night of the 16th, as many of Middleton’s corps artillery units were ordered out of the sector, the Golden Lions hung on, in many cases unaware of the danger their forward units were in. They were determined to retain control of the Roth–Auw road, which would otherwise give the 18th Volksgrenadiers control of the northern sector of the 106th’s front, abutting the Losheim Gap. Equally important was the southern town of Bleialf – which boasted a population of over 1,000 and a railway station – and the route that ran from it to Schönberg, for dominance of that area would determine whether any of the Golden Lions could receive reinforcements – or withdraw.

Defending Roth, a gaggle of two dozen fieldstone houses and barns, Captain Stanley E. Porche’s Troop ‘A’ of the 18th Cavalry fought through the morning but were forced to surrender in the afternoon of the 16th. Bleialf, in the gap south of the Schnee Eifel hills, had, meanwhile, been surrounded and attacked since early on the 16th. It was a more significant town with several large mills and warehouses, for the area had prospered on lead mining for centuries (Blei meaning ‘lead’ and the Alf being the local stream). Corporal Hal Richard Taylor had been stationed there for a few days before the attacks came in, and remembered when the first barrage lifted: ‘The whole damned German army, it seemed, came right at us, yelling and cheering as if it were a football game!’ The ill-disciplined young grenadiers belonged to Oberstleutnant Witte’s 293rd Volksgrenadier Regiment.

During a lull in the struggle for Bleialf, the GIs called to some of the Volksgrenadiers to surrender; two stepped forward to obey, but were ordered back by their sergeant. The grenadiers stood there for a moment, undecided on what to do, eventually heading towards the American lines, whereupon their sergeant shot them dead. In clearing the town, Taylor remembered a driver ‘a big man, about 200 pounds … could lift twice his weight’ who worked his way through buildings in Bleialf, bayoneting Germans. As he did so, ‘he also hoisted them through the windows on his bayonet as if he were spearing hay with a pitchfork. Then he would shake them loose and let them drop to the ground below … As he pitched the freshly-slain Volksgrenadiers, everyone – Germans included – ceased fire and watched, awe-struck.’ Eventually the pitch-forker fell, but Taylor ‘counted more than thirty bayoneted Germans whom he had killed’. Sadly, it seems, medals and recognition escaped this unnamed hero.

In a counter-attack at noon, Taylor’s group in Bleialf had started to repel the Germans and under Captain Warren G. Stutler from the 423rd’s Headquarters Company began to clear the town. They were joined by men from the 81st Combat Engineers, members of the Regiment’s Cannon Company and cooks and clerks from Headquarters and Service Companies, none of whom were trained riflemen. This motley crew ousted the Germans from Bleialf and formed a ‘provisional battalion’ under Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick W. Nagle, executive officer of the 423rd – but at high cost. Of the 176 officers and enlisted men from the 81st Engineers who helped eject the Volksgrenadiers from Bleialf, only forty-six returned to their parent unit.

Although the official histories suggest that Bleialf was taken on the 16th, Taylor’s evidence is at odds with this. He recorded that his unit of the 423rd Infantry kept its foothold in the key village, supported by US artillery, into the next morning and withdrew only when ordered by radio just before dawn on the 17th. Early that morning, Coleman Estes of the division’s 81st Combat Engineer Battalion remembered the frozen bodies of the dead, German and American, twisted in their final tortured moments of combat, ‘looking like wax sculptures in the snow’. John Kline saw Bleialf after the battle, too: ‘There was much evidence that a large-scale battle had just taken place … a real shoot-out, with hand-to-hand fighting. Dead Americans and Germans lay in doors, ditches and hung out of windows.’ After the GIs departed, Bleialf was overrun, allowing German armour to make its way towards Schönberg virtually unopposed. Accounts of the Bulge suggest little or no activity in the air by either side on 17 December, but Taylor witnessed ‘a roar and saw a P-47 [Thunderbolt] right on the tail of a Focke-Wulf. The P-47 scored a hit and the German plane crashed. A few seconds later another P-47 tailing a Messerschmitt shot it down about half a mile away. Those were the only Allied planes I saw in the battle.’

Apart from General Jones’s surreal conversation with his corps commander of 16 December, when Jones had thought Middleton was directing him to keep his two units on the Schnee Eifel, and Middleton thought he had ordered the opposite, poor communication between the 106th’s regiments and St Vith led to even more confusion over what exactly to do during the night of the 16–17 December. It was becoming clear to all that the Golden Lions’ 422nd (to the north) and 423rd Regiments, between Auw and Bleialf, were in danger of being bypassed. Incredibly, many in the two regiments had yet even to fire a shot, but already their only hope of survival lay in withdrawing from the Schnee Eifel and stopping the Germans at Schönberg, with its heavy stone bridge across the Our river. It did not happen: as we have seen, Jones had erroneously ordered them to stay in place, thinking that was Middleton’s wish. Schönberg was overwhelmed swiftly on 17 December with its vital bridge intact (it had not even been prepared for demolition) and that night both Manteuffel and Model, who liked to be up front with the troops, met in its cobbled streets. ‘I’m sending you the Führer-Begleit-Brigade’, the élite unit of troops who had once guarded Hitler and had their own tanks, the field marshal told the Fifth Army’s commander, amidst the chaos of the newly captured town, clogged with transport, prisoners and wounded. The Golden Lions’ fate had been sealed.

With German armour controlling the Auw–Schönberg–St Vith road, as well as the route to Bleialf, the two US regiments withdrew to the higher ground of the Schnee Eifel to regroup. Their situation was not desperate: they had a day’s supply of K-rations, ammunition, water, their own transport, but the swiftness of the German advance had meant they were unable to evacuate their casualties and were short of surgical supplies. They had the use of logging trails between their positions – which would soon turn to mud with frequent use – but the Germans controlled the road network below, which is what counted. Their biggest problem was that they were inexperienced and lacked dynamic leadership – both the regimental colonels, Cavender of the 423rd and the younger Descheneaux of the 422nd, tended to wait for orders rather than make their own decisions.

One thing was obvious, apart from the fact that the 422nd and 423rd were surrounded: they had to regain the initiative. The last message received from the Divisional HQ in St Vith at 8.00 p.m. on the 18th made it clear that it was imperative Schönberg be retaken. Overnight, the GIs moved out of their positions on the Schnee Eifel under cover of heavy fog, and prepared to seize the town, then move westwards towards St Vith. By this stage, the two regiments had separated, contact between them was lost and every unit had taken a few casualties. Artilleryman Pete House, with Lieutenant-Colonel Vanden Lackey’s 590th Battalion, remembered that as the 18th ended, ‘we were exhausted, hungry and cold. Cooks had not prepared any meals since the morning of the sixteenth. I received no emergency rations. Cold weather clothing and bedding was never issued. That night we moved to an open field. We only had four rounds for our 105 mm howitzers left. We received orders to destroy all the equipment and be prepared to hike back to our lines. It was with great pleasure that I destroyed two 610 FM communications radios with a pick as they had rarely worked.’

Corporal Taylor noted that his Anti-Tank Company, usually numbering over a hundred men, had dwindled to about thirty. On the evening of the 18th, Technical Sergeant Willard F. Nelson, with the 422nd Regiment, remembered having to shoot his way through a mob of advancing Germans, using the .30-inch calibre machine gun mounted on his jeep. He was the company clerk and had never fired the gun before; the vibrations broke the windshield. Loaded with all the company records, Nelson and his driver careered away to safety. ‘About two miles later, we went around a corner too goddamned fast, tipped the Jeep over. It was upside down and I got thrown into a ditch. I remember spending the night in that ditch.’

The battalions were moved into assembly areas before daylight on the 19th, and at 08.30 a.m. battalion commanders were given orders for their attack on Schönberg to begin at 10.00 a.m. However, caught between German positions in Auw and Bleialf, from 09.30 a.m. the 423rd Regiment started being subjected to heavy artillery concentrations, which killed one battalion CO and several company commanders. John Kline of Company ‘M’, the 423rd’s Heavy Weapons outfit, remembered the move towards his destination, ‘a heavily wooded area (Linscheid Hill, marked as Hill 546 on the map) southeast of the town … I was with a .30-inch calibre machine-gun high on a hill, overlooking a slope leading into a valley. I could see, about 1,000 yards to the northwest, the house tops of Schönberg.’ Kline assessed that the hostile artillery barrage came from German anti-aircraft units firing uphill from Schönberg. ‘Those guns were a decisive factor in the outcome of the battle,’ he felt. ‘We had very little artillery support. I learned after the war that the 423rd’s artillery support was overrun by the Germans troops.’

The attacks went in, but the 1st and 3rd Battalions lost heavy casualties and became pinned down by artillery fire from the Flak guns. The Volksgrenadiers had massed these around Schönberg to protect the Our bridge and vehicle convoys on the main road to St Vith, but turned them instead on the GIs rushing down the tree-studded slopes above. The result was devastating: many of the companies were scattered and overwhelmed, or destroyed, piecemeal. The 2nd Battalion moved to the right and attached themselves to the 422nd Infantry Regiment. Gunner Pete House recalled to me: ‘When it became daylight on the nineteenth we moved up a steep field to the left and went into firing position along the edge of the woods – with only four 105mm rounds left. I opened a can of pork and gravy that we had “borrowed” from the navy while on the LST crossing the English Channel and was heating it when the Germans hit us with everything. Of course I should have dug a foxhole. One of the guys had borrowed my shovel so I ran into the woods looking for a stream bed for protection.’

Corporal Taylor watched these attacks ‘from a grandstand seat’, thinking the sight ‘a scene of pure hell. As hundreds of men surged down the hill, the German artillery fired on them and shells exploded in the pine trees overhead. With that the men panicked and ran back up the hill,’ he remembered. ‘Officers yelled and swore at the men to form into an organised body, again and again. Three times, maybe seven times, this happened until finally the exhausted men simply sat down to rest, despite the urgings of officers who obviously were also exhausted and frustrated at the turn of events.’ The attempt to retake Schönberg had been a disaster. The men were now scattered in small groups in the hills above the town, low on food and ammunition.

At 3.45 p.m., Colonel Cavender called a conference and several witnesses recalled his comments. ‘“There’s no ammunition left”, he began, “I was a GI in World War One and I try to see things from their standpoint. No man in this outfit has eaten all day and we haven’t had water since early morning. Now, what’s your attitude to surrendering?”’ The answer was stupefied silence. Then hostility. Cavender, with uncharacteristic decisiveness, settled the matter: ‘Gentlemen, we’re surrendering at 4.00 p.m’. Corporal Taylor was flabbergasted at what happened next. ‘Then small bodies of men began to hold up their hands. They were starting to surrender. We couldn’t believe what we were seeing.’

The fact that the regiment was ordered to surrender, against the better judgement of many, only made it worse, and created a deep rancour that endured for decades. Some GIs begged their officers and NCOs to be able to continue the fight. PFC Kurt Vonnegut, a regimental scout, wanted to slink off and carry on fighting, but instead raged at his own powerlessness, having no food and only a few rounds of ammunition. He found somewhere to lie down and wait. Several others collapsed in exhaustion beside him; someone suggested they fix bayonets and die fighting. From the forest surrounding them a German-accented voice, amplified by a loudspeaker, echoed through the late afternoon gloom. ‘Come out!’ ordered the voice. Vonnegut got to his feet, raised his hands and joined what he later termed ‘the river of humiliation’. A historian of the Golden Lions recorded that from about 4.00 p.m. on the 19th and throughout 20 December, a German loudspeaker van played ‘American jazz intermingled with hearty invitations to come in for hot showers, warm beds and hot cakes for breakfast’. However, a few volunteers led by Staff Sergeant Richard A. Thomas eventually put an end to ‘Berlin Betty’s playful reference to the joys of playing baseball in a POW camp’ with a ‘well-directed hand grenade’.

This sort of runaway success inspired one Landser to write home: ‘We shall probably not have another Christmas here at the front, since it is absolutely certain that the American is going to get something he did not under any circumstances reckon with. For the “Ami”, as we call him, expected he would celebrate Christmas in Berlin, as I gather from his letters. Even I, as a poor private, can easily tell that it won’t take much longer until the Ami will throw away his weapons. For if he sees that everybody else is retreating, he runs away and cannot be stopped any more. He is also war-weary, as I myself learned from prisoners.’

Colonel Descheneaux’s 422nd Regiment to the north of Cavender’s 423rd suffered similar setbacks. When tanks appeared on the Roth, Auw and Schönberg roads, they were initially misidentified as being from the US 7th Armored coming to their rescue. The let-down was cruel when the force, actually belonging to Otto Remer’s Führer-Begleit-Brigade, raked the GIs with fire. Descheneaux sensed he was surrounded and powerless to resist further. Corporal Stanley Wojtusik of the 422nd hadn’t eaten for three days and remembered his regiment ‘was short of bazookas. I don’t know if they would have really stopped those tanks unless you hit them right in the bogey wheels – we surely couldn’t stop them with our M-1 rifles. We were able to shoot most of the ground troops, but we had no defence against the tanks.’ From his ditch near the overturned jeep, Willard F. Nelson recalled ‘someone shouted “the tanks are coming, we got help”. See, [the caterpillar tracks of] tanks sound like a million mice screaming, they squeak. So, they came up over the hill and “Jesus Christ, that’s good, here’s the tanks” but they was German tanks. We surrendered.’

Some troops, like PFC Leon Setter of Headquarters Company in the 422nd had no idea of the situation. He spent 16 and 17 December guarding the 2nd Battalion’s HQ in a pillbox two miles east of Schlausenbach. Setter was in complete ignorance of the coming catastrophe, merely on a ‘class-one alert because of enemy activity in the area’. His squad moved out through a fire-fight on the 19th and that afternoon to his amazement, ‘My squad leader called us together and told us our situation looked bad. We were surrounded. He concluded by telling us to dig foxholes to protect ourselves from the shelling.’

Aware of Cavender’s mood, Colonel Descheneaux called a conference of his own officers at his headquarters, which was situated next door to the regimental aid post. ‘I don’t believe in fighting for glory if it doesn’t accomplish anything. It looks as if we’ll have to pack it in.’ His friend, Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas P. Kelly of the 589th Artillery, objected, ‘Jesus, Desh, you can’t surrender’. Descheneaux looked at the mounting pile of dead and wounded. ‘As far as I’m concerned, I’m going to save the lives of as many as I can. And I don’t give a damn if I am court-martialled!’ Medical Sergeant Bud Santoro remembered the tree bursts from the German Flak guns – ‘a tinkling rustling as the deadly shrapnel rained down’. After tending over twenty casualties, he climbed the hill to the regimental aid post. He saw Colonel Descheneaux and told him they needed to evacuate the casualties for better medical attention. Santoro remembered the tears in his colonel’s eyes as he was told ‘It’s OK, there’ll be evacuation, Sergeant. We are surrendering’. Leon Setter was perplexed. ‘As I finished digging my hole, the squad leader returned to tell me that Colonel Descheneaux had ordered the entire 422nd Regiment to surrender and destroy our weapons. Needless to say, I was confused. This had been my first day in actual combat. What was going to happen next?’

“The 106th Infantry Division” Website

“Snow and Steel: the Battle of the Bulge 1944-45” by Peter Caddick-Adams