The three key players on Eisenhower’s staff who would have a pivotal role in planning SHAEF’s response to the Ardennes were its ubiquitous chief of staff, Walter Bedell Smith (known as ‘Beetle’ because of his nervous energy), and the British officers Kenneth Strong and Major-General J.F.M. ‘Jock’ Whiteley, its Deputy G-3. The latter had worked for Eisenhower since late 1942 at Allied Forces HQ in the Mediterranean and was one of the few British officers Ike positively insisted on taking with him to SHAEF in 1943. Although he was officially Deputy G-3, Whiteley’s ability, trustworthiness and general likeability was such that ‘the Beetle’ also employed him as an unofficial deputy chief of staff. Whiteley was particularly valuable because of his close personal bond with Monty’s chief of staff, the affable Major-General Francis ‘Freddie’ de Guingand, although the relationship between the two headquarters was tempestuous. Noel Annan, a British intelligence officer at SHAEF, noted how ‘it became the mark of a good British SHAEF officer to express dismay at the behaviour of Montgomery. Had he not challenged Eisenhower’s broad-front across France? Had he not then intrigued to be reinstated as Commander in Chief of land forces and usurp Eisenhower’s position? Did he not treat Eisenhower with contempt, refusing to visit him at his headquarters?’ To prevail against this new threat, the Allies would need to put aside such personal differences – if they could.

That first evening, with maps spread out on the floor, Bedell Smith, Strong and Jock Whiteley reasoned the road network of the Ardennes led the eyes of even a casual observer straight to the two transportation hubs of St Vith and Bastogne. Control of both these towns would regulate the speed and extent of any German advance. Apparently using an ancient German sword (of all portentous items), tracing routes and pointing to towns, they went on to deduce correctly that the German attack was aimed at splitting the British and US army groups. It was equally clear to them that, to manage the German penetration, its flanks needed to be contained, preferably at the northern and southern shoulders; the corridor in between could then be controlled and eventually choked, like slowly sealing a breach in a dam. After Bedell Smith was assured that reinforcements could reach Bastogne in time by road, they recommended this course of action to Ike.

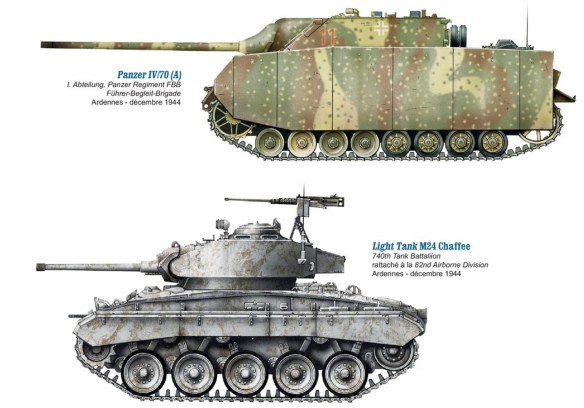

Thus, Eisenhower alerted his only strategic reserve available – the 17th, 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions – for emergency deployment to the Ardennes. That was his function as the strategic commander. The 82nd and 101st were already in France and could move immediately; the 17th would have to fly from England when weather permitted. There are, however, certain rules in the management of a military command chain that make for smooth running; one of these is that the man at the top should never bypass several levels of command to issue direct orders to those at the bottom – principles that Montgomery and Patton often forgot, or ignored. In terms of operations, Eisenhower had no wish to bypass or overrule his friend Bradley in the latter’s command of Twelfth US Army Group. Ike would advise, but not order.

While Ike had alerted his strategic reserves, with the 82nd Airborne eventually destined for Werbomont, on the northern flank, and the 101st for Bastogne, it was up to Bradley to deploy his operational reserves. Eisenhower felt he needed a nudge: ‘I think you’d better send Middleton some help,’ he advised. Fortunately, there were two newly arrived US armoured divisions, William H. Morris’s Tenth, nicknamed ‘the Tigers’, with Patton’s Third Army, and Robert W. Hasbrouck’s 7th Armored in Simpson’s Ninth Army sector, north of the Ardennes. Bradley was openly reluctant to order the effervescent Patton to surrender his newest armoured division which would, he knew, trigger howls of profane outrage and protest. ‘Tell him that Ike is running this damn war,’ Eisenhower told his friend.

Thus Patton was summoned to a secure telephone link in his ‘Lucky Forward’ headquarters at Nancy and ordered by Bradley’s chief of staff, Major-General Leven C. Allen, to commit the 10th Armored straightaway, sending one of its Combat Commands immediately to join the 101st Airborne, also just directed to Bastogne. There was, as predicted, a heated debate. ‘As the loss of this division would seriously affect the chances of my breaking through at Saarlautern, I protested strongly,’ wrote Patton later, ‘saying that we had paid a high price for that sector so far, and that to move the Tenth Armored to the north would be playing into the hands of the Germans.’

Bradley then had to make a personal telephone call after Allen to nudge Patton into compliance. ‘General Bradley admitted my logic, but said that the situation was such that it could not be discussed over the telephone.’ The armoured division was to report to Troy Middleton at his VIII Corps headquarters in Bastogne, which both readily identified as a key intermediate objective for any force in transit through the Ardennes. Although from his command post at the Caserne Molifor Patton may have protested vigorously, he was also aware of the intelligence concerns of his own G-2, Colonel Oscar Koch, a man he trusted, and who had been part of his intimate command group since Tunisia, over eighteen months earlier. Koch had predicted a German attack, and there it was. Eventually, Patton fell into line because he saw the opportunities for an offensive, if different from the one he had planned.

The US Ninth Army commander, William Hood Simpson, was (in Bradley’s words) ‘big, bald and enthusiastic’. From his headquarters in Maastricht, code-named ‘Conquer’, he was altogether more gracious than Patton in surrendering his 7th Armored Division on 16 December and sending it to St Vith. This was the ‘Workshop’ formation that Middleton had told the beleaguered General Jones, of the Golden Lions, was on its way to help him. The professionalism of Simpson’s Ninth Army was demonstrated by the speed with which the 7th Armored Division reacted to the order to move to St Vith. They were first warned on 16 December at 5.45 p.m. to move south as soon as possible, with an advance party leaving 105 minutes later: an impressive achievement even by the standards of today. Simpson was a West Point classmate of Patton’s, and regarded as extremely capable; his headquarters ‘was in some respects superior to any in my command’ thought Bradley, while possessing none of the defects of First Army’s. Eisenhower observed of his dependable and professional Ninth Army commander, ‘If Simpson ever made a mistake as an Army commander, it never came to my attention. Alert, intelligent, and professionally capable, he was the type of leader that American soldiers deserve.’

Simpson had served in France in 1918, latterly as a divisional chief of staff, and progressed through Leavenworth and War College to reach three-star rank by 1943. Simpson’s own chief of staff was General James E. Moore and the two forged an unusually close relationship, where, in the words of Simpson’s biographer, ‘they understood, trusted and admired each other … Often while Simpson was in the field, Moore would issue orders in the Commander’s name, then tell Simpson later. So closely did the two work together that in many instances it is impossible to sort out actions taken or ideas conceived.’ This in so many ways reflected the synergy needed for a successful campaign headquarters.

After D-Day, when Simpson sent his staff officers to study how First and Third Armies worked, the differences between the two were analysed thus: ‘First Army, probably reflecting its Chief of Staff Kean’s suspicion and resentment of outsiders, would allow only Simpson and his chief of staff to visit his headquarters and staff sections. On the other hand, Simpson’s West Point classmate, Patton, allowed anyone from Simpson’s staff to visit his army – all were welcome at Third Army headquarters.’ The amenable Simpson and his Ninth Army had also already served under Montgomery for a while, a development which Bradley felt would not have worked so well with Hodges, and certainly not Patton. As the winter set in, there are records that Simpson, with more foresight than his fellow army commanders, ‘directed the initiation of a massive supply effort designed to issue winter clothing’ to his troops. Eisenhower found an echo in Simpson, who was one of the most diplomatic of American commanders, having charmed Montgomery and hosted the important 7 December conference at his Maastricht headquarters.

Late on 16 December, as soon as Simpson’s headquarters received the order to despatch the 7th Armored, its Combat Command ‘B’ under Brigadier-General Bruce C. Clarke went on ahead to liaise with Middleton in Bastogne, before moving on to St Vith, where Clarke arrived towards midday on 17 December. The rest of Clarke’s formation battled against the flow of retreating traffic to arrive soon afterwards and deployed from their line of march straight into combat. Clarke’s early arrival ensured that St Vith would be held until 23 December, and bought a valuable week for the Americans to stymie the Germans and reorganise themselves. In due course, Clarke would take over command of St Vith from the traumatised General Jones of the Golden Lions. While it may have been Clarke’s personal drive that brought him to St Vith in time, it was Simpson’s tutelage that prepared him for his starring role in the drama unfolding. From the beginning, it was Simpson, far more certainly than Bradley or Hodges, and less grudgingly than Patton, who identified the German attacks as a major offensive and offered what help he could, sending not only 7th Armored, but the 30th Infantry and 2nd Armored Divisions as well. Within ten days, Simpson’s Ninth Army had committed seven of its divisions to battle in the Ardennes.

The way these decisions came about challenges the view that the Ardennes was all ‘prearranged’, from the American perspective; that Middleton’s front was deliberately weak in order to lure the Germans out from the safety of their Westwall and attack with their remaining panzers; that two US armoured divisions had been stationed north and south for just such an eventuality; and that Eisenhower and Bradley were prepared to sacrifice the lives of tens of thousands of GIs to bring about an early end to the war. In The Last Assault, Charles Whiting had looked at the end result, then worked back to spin his speculative conspiracy. The circumstances of the two armoured divisions’ arrivals in theatre, the timing of the German attack and Patton’s protests serve to undermine his argument.

With the decisions to alert the airborne forces and move their armour finalised for the moment, there was little else the pair could do, so Eisenhower and Bradley returned to their five rubbers of bridge, accompanied by the Scotch whisky to celebrate Ike’s promotion, an honour Bradley would one day receive himself.

On the morning of 17 December, Eisenhower, in a demonstration of his true self-confidence, sent a letter to Marshall, his boss, shouldering the blame for the surprise, but concluding, ‘If things go well, we should not only stop the thrust, but be able to profit from it’. One might have thought Bradley sufficiently concerned to have raced back to his own headquarters in Luxembourg first thing on 17 December, as ‘Monk’ Dickson had done, but he lingered at the Trianon Palace, perhaps to get more of the picture. It was remarkably fortunate that Bradley was in Paris with Eisenhower when the news first broke. Had the two commanders been in their own separate headquarters, Ike may well have deferred to Bradley’s more sanguine views of the situation – being much closer to the Ardennes – and Hitler might have gained at least another day. Bradley, too, demonstrated that he needed a nudge from Ike to deploy the two armoured divisions, as well as some moral back-up from his boss to confront an angry George Patton, sore at having to surrender his 10th Armored Division.

Meanwhile, Eisenhower and his SHAEF staff, now energised by having a ‘real’ campaign to fight, rather than pursuing endless turf wars over logistics and civil affairs, developed a response to the Ardennes attack. In some ways, SHAEF could be its own worst enemy. Noel Annan, working on its intelligence staff, described the set-up:

Supreme headquarters was gigantic. The forward echelon [at Versailles] to which I belonged was equivalent in numbers to a division; how large the rear echelon was I never discovered. Strong’s [intelligence] staff alone numbered over a thousand men and women. It was not as if the vast staff helped Eisenhower to make strategic decisions: they had already been taken at meetings between Eisenhower, his army group commanders and General Patton … as a result the plans SHAEF produced were rarely clear or convincing, since they were a series of compromises; and the staff spent more of their time producing papers to justify these decisions to the Combined Chiefs of Staff than in producing the data on which plans could be made … intelligence at SHAEF had been governed by what one might call the ‘Happy Hypothesis’, that the German Army had now been so shattered in Normandy and battered in Russia that it was only a matter of two or three months before the war would end.

Big modern military operations, such as those seen in Bosnia, Iraq and Afghanistan (in all of which I worked), are baffling assemblies of very senior staff officers of many nations writing reports and advancing national agendas; they can best be summed up by the term ‘warehouse generalship’, where colonels are more in abundance than corporals. Noel Annan’s diaries prove that today’s coalition headquarters are merely slimmed-down versions of SHAEF in 1944–5. The tens of thousands of personnel comprising SHAEF rear echelon had remained in London. SHAEF Forward (code-named ‘Shellburst’) moved twice in September 1944, first to Granville on the Cherbourg peninsula, thence to Paris. ‘No one can compute the cost of that move in lost truck tonnage to the front,’ Bradley lamented privately, at the height of the logistics squeeze.

This shatterproof, semi-transparent balloon, of the sort in which modern politicians tend to live, is what Eisenhower had overcome with his clear thinking, unattended by distracting minions, on that December night with Bradley when the crisis was first apparent. Everyone realised that their most powerful weapon – the Allied air forces – would remain grounded for the foreseeable future as the bad weather made any aerial response impossible; they were going to have to learn how to craft a land campaign for the first time without the assumption of lavish aerial support. Initially their stratagem would be to contain the German counter-offensive east of the River Meuse, allowing the First and Third Armies breathing space to devise a coordinated plan to destroy it.

Having ordered the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions to the Ardennes by truck in great haste, Ike also called over the 17th Airborne Division from England, and summoned Major-General Matthew B. Ridgway’s XVIII Airborne Corps headquarters to command the three divisions. Days earlier, Ridgway had accompanied senior commanders of the 101st (the ‘Screaming Eagles’, after their shoulder insignia) back to England to lecture on their experiences during Market Garden. He had already sent its commander, Major-General Maxwell D. Taylor, back to the US on 5 December for staff conferences in Washington, DC. Thus the commanding generals of both the XVIII Airborne Corps and 101st were out of country when the storm broke in the Ardennes. Major-General James M. Gavin and Brigadier-General Anthony C. McAuliffe, the latter normally in charge of 101st’s artillery, were in temporary command of the corps and division, respectively. With so many of the senior leaders out of theatre, their airborne troopers reasoned, they were unlikely to be deployed in combat operations in the near future.

A West Pointer, class of 1917, Ridgway had taken over the 82nd Infantry Division from Omar Bradley in 1942 and converted it into an airborne force. In mid-training the 82nd lost a cadre, taken away to form the nascent 101st Airborne, and thereafter a fierce rivalry developed between the two divisions. At that time, Ridgway commanded the former, with Max Taylor leading the division’s artillery and Gavin a regiment of its parachute infantry, and in due course they became arch-competitors. After Major-General Bill Lee, the 101st’s commander, was incapacitated by a heart attack in 1943, Taylor left to lead it, and the rising star, Gavin, moved up to become Ridgway’s number two and chief planner for airborne aspects of Normandy. Afterwards, when Ridgway rose to command the XVII Airborne Corps, Gavin replaced him as commander of the 82nd (known as the ‘All American’, as the original formation contained men from every state), mirroring Taylor’s position at the 101st. Ridgway earned his spurs commanding a corps in Market Garden, and – reasoned Ike – a spare, battle-tested, higher-formation headquarters led by a reliable commander was always a handy asset to have in a fluid campaign.

In December 1944, Jim Gavin was the US Army’s most experienced airborne soldier and its youngest divisional commander. Illegitimate and adopted, he had joined the army underage, was largely self-educated, and fought hard to win a place at West Point, graduating in 1929. He worked his way up through sheer ability to command a regiment of the 82nd in Sicily, where he won a Distinguished Service Cross and promotion to brigadier-general. After Normandy he was the natural successor to command the 82nd when Ridgway was promoted to command the Airborne Corps. The rivalry between Taylor of the 101st and Gavin grew more intense as each rose to higher responsibilities, both vying to be ‘Mister Airborne’ in the public mind, with the youthful Gavin normally capturing – and conquering – an admiring female fan club.

After the liberation of Paris, Gavin had joined a distinguished table at the Ritz for lunch, where the other guests were Ernest Hemingway, Collier’s war correspondent Martha Gellhorn (then Hemingway’s wife), Hemingway’s mistress Mary Welsh and Marlene Dietrich. Gavin’s drive and youth were irresistible to Gellhorn, and the two swiftly embarked on an affair. Gellhorn would be reporting in Italy when the Bulge broke, but managed to reach Belgium to cover the closing stages in January. In the meantime, Gavin had become ensnared by the charms of the other unattached lunchtime guest, Marlene Dietrich, who was ‘crazy about him’ during her pre-Ardennes tour of France and Belgium. In between, he indulged with his pretty English WAC driver.