It was not until 410 BC that Carthage’s seventy-year sabbatical from Sicilian affairs came to an end, when it was decided to lend help to the city of Segesta in a dispute that had flared up with its Greek neighbour Selinus. The reason for this foreign-policy volte-face probably had more to do with increasing concerns over the growing influence of Selinus’ ally Syracuse than it did with solidarity with Segesta. After the death of Gelon in 478, Syracusan power had quickly waned and Sicily had once more become a patchwork of feuding city states and minor warlords. Economic and demographic decline had quickly followed, with many mainly Elymian settlements in western and central Sicily contracting greatly in size or even being completely abandoned. However, by 410, after spectacularly repelling an Athenian invasion, Syracuse began to re-emerge as a major power on the island–one that might potentially take advantage of the continuing turmoil in western Sicily.

Segesta and Selinus were located in the west of the island, close to the Punic cities of Motya, Solus and Panormus, which, although politically independent of Carthage and neither significant markets for Carthaginian goods nor major exporters to the city, were still of great strategic importance to Carthage, being key coordinates on the trade routes that linked the North African metropolis with Italy and Greece. The sense of a renewed Syracusan threat may have been the stimulus for the construction of a new system of fortifications at Panormus. The Greek cities of Sicily were also important trading partners. Diodorus, taking his information from earlier Sicilian Greek historians, explained that the enormous wealth of the city of Acragas in the late fifth century came in part from supplying olives to the Carthaginians. The Carthaginian economic hegemony in the central Mediterranean appears to have been built around the control of foreign trade. Profit was gained not only through Carthage’s own participation in this trade, but also from taxing foreign merchants who wished to operate in markets for which Carthage increasingly provided ‘protection’, such as the Punic cities on Sardinia and Sicily. Moreover, allies could be rewarded by the grant of trading rights in ports over which Carthaginian influence extended. Initially, at least, Carthaginian intervention in Sicily was driven by the desire to protect this system.

For the Magonids, there were other, more personal, considerations. Carthage might have become the richest and most powerful state in the western Mediterranean under their stewardship, but the disaster at Himera remained a blemish on that proud record. Magonid prestige at home would undoubtedly be boosted by a triumphant return to Sicily. Now that major domestic constitutional reforms had been bedded in, the Magonids may have considered this a good time to act abroad. Unsurprisingly, it was Hannibal, the present leader of the Magonids and the grandson of Hamilcar, the defeated commander at Himera, who was the main advocate within the Council of Elders for Carthage lending assistance to Segesta. When that assistance was agreed, in 410, he was put in command of the expeditionary force.

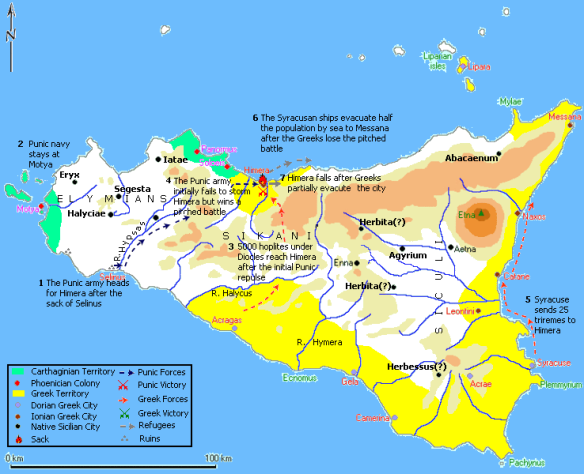

In an attempt to ensure that the Syracusans did not become militarily involved in the dispute, the Carthaginians sent envoys to Syracuse requesting their arbitration. This strategy delivered the desired result when the Selinuntines refused Syracusan intervention. The Syracusans then decided to renew their alliance with Selinus while maintaining their peace treaty with Carthage, thereby staying neutral. The Carthaginians then sent 5,000 Libyan and 800 Campanian mercenaries, supplying them with horses and high salaries, to assist the Segestans.

After the Segestans with their hired military help had routed a Selinuntine army, both sides turned to their respective allies, Carthage and Syracuse, for help, which was granted, thereby putting the two great powers on a collision course. Preparing himself for war, Hannibal mustered a formidable army made up of Libyan levies and Iberian mercenaries, and started to prepare the necessary sea transportation to carry his army across to Sicily. After these troops, siege engines, missiles and all the other equipment and supplies that were needed had been loaded into 60 ships and 1,500 transports, in 409 the armada set off.

Once it had safely landed, the army was joined by Carthage’s Greek and Segestan allies, before marching directly to Selinus, where Hannibal, aware that the Selinuntines were holding out for the arrival of Syracusan allies, did everything in his power to capture the city as quickly as possible. Giant siege towers were dragged up to the walls, and battering rams were taken to the gates. Archers and slingers were also employed to keep up a constant stream of missiles. (Unfortunately we are almost completely reliant on the extremely hostile (and much later) testimony of the Sicilian Greek historian Timaeus for information on this, and later, Carthaginian military campaigns in Sicily. Though he provides a considerable amount of information on Carthaginian troop movements, much of his analysis needs to be treated with extreme caution.)

The Selinuntines had recently spent so much effort and expense on the construction of a series of magnificent temples that they had neglected the repair of their city walls. The Carthaginian siege engines soon punched holes in these fragile defences, and battalion after battalion of fresh troops were thrown at the breaches. However, knowing how catastrophic the consequences of defeat would be for them, the citizens of Selinus mounted a desperate defence that held the Carthaginians at bay for another nine days. Indeed, it was only when, in a moment of confusion, the defenders withdrew from the walls that the Carthaginians gained access to the city. Despite this piece of good fortune, progress was still painfully slow, as each street had to be taken by fierce hand-to-hand fighting while women, children and old men rained stones and missiles down upon the heads of the Carthaginian troops. The end arrived when the Selinuntines, who had at last run out of options, made a futile last stand in the marketplace. After a fierce fight, they were all cut down. Diodorus (once more following Timaeus’ hostile testimony) then provides a vivid, but one suspects highly partisan, account of the supposed outrages inflicted on the city and its surviving inhabitants by the Carthaginian troops, which he contends left the streets of the city choked with 16,000 corpses and many buildings burnt to the ground.

Hannibal’s next target was surely no surprise to its inhabitants. Using the same tactics that had been so successful at Selinus, the Carthaginian army hit Himera with a sustained, high-tempo assault. However, the Himerans, deciding that attack was the best form of defence, marched out of the city and, as their families cheered them from the walls, attacked the Carthaginian army. Although initially startled by this unexpected tactic, the numerically superior Carthaginian forces eventually managed to drive the Himerans back into their city. There the decision was now taken to evacuate as many of the citizenry as possible on Syracusan ships. Those left behind were instructed to hold out as best they could and wait for the Syracusan fleet to return for them. It never did, and on the third day the city fell. Once more Diodorus provides a lurid account of the outrages committed, on the orders of Hannibal himself, by the Carthaginian troops. Unlike Selinus, which had only its walls destroyed, Himera was to be razed to the ground and its famous temples pillaged. Hannibal then supposedly rounded up the 3,000 men who had been taken prisoner and, in a bloody memorial to his grandsire, slaughtered them at the very spot where it was said that Hamilcar had fallen. After that, rather than pressing on and taking full advantage of the Sicilian Greeks’ disarray, the Magonid general paid off his army and returned to Africa.

Despite the strictly limited nature of Hannibal’s Sicilian operation, there is little doubt that it had set an important precedent for future Carthaginian intervention. Carthage’s extensive use of mercenary troops resulted in the production of the city’s first coinage to pay them. Previously Carthage had resisted the introduction of coinage, which had first appeared in the Greek world at the beginning of the sixth century. However, the Punic cities of Sicily, clearly influenced by their Greek counterparts on the island, had started minting their own coinage much earlier, in the last three decades of the sixth century.

As their chief purpose was to pay mercenaries, who wished to have high-value Greek-looking coinage, the new Carthaginian coins borrowed heavily from western Greek designs and weight standards. They were decorated with two motifs that became increasingly associated with Carthage: the horse and the palm tree. They carried one of two superscriptions: Qrthdst (‘Carthage’) or Qrthdst/mhnt (‘Carthage/ the camp’). The latter term, which basically meant ‘Carthaginian military administration’, is surely confirmation that the coins were only for a specific purpose. Carthage’s lack of a permanent presence in Sicily at this time is highlighted by the fact that the troops were recruited and drilled in Africa, and it appears that the supplies and coinage were also shipped from Carthage.

There were now clear signs that Hannibal’s actions had further destabilized the island. Within two years, in 407, Carthaginian troops were back on Sicily after Hermocrates, a renegade Syracusan general, had attacked the Punic cities of the south-west. Despite Diodorus’ assertion that their aim was the conquest of the whole island, the Carthaginians were wary of taking further unilateral action. The discovery of a partial inscription in Athens shows that the Carthaginians sent envoys there to seek an alliance. The Carthaginian heralds received a warm welcome, and were invited to participate in civic entertainment. The inscription appears to have been a positive recommendation from the Athenian council that steps should be taken to cement such an alliance if the wider citizen assembly ratified it. The council also recommended the dispatch of a diplomatic mission to Sicily to meet with the Carthaginian generals and assess the situation. However, even if this alliance was sanctioned, the Athenians, stretched by long years of conflict with Sparta, provided no practical assistance to Carthage.

After collecting together another sizeable army, made up of Carthaginian citizens, North African allies and levies, Hannibal and a younger colleague, Himilcar, set out for Sicily.66 However, the campaign got off to an inauspicious start. First the fleet was attacked by the Syracusans, with the resulting loss of a number of ships and the remainder of the flotilla having to flee into the open sea.67 Then, after the army had managed to land on Sicily and had started to besiege the exceptionally wealthy Greek city of Acragas, it was struck by an outbreak of plague that killed many men, including Hannibal. Diodorus, taking his cue from Timaeus, records the questionable detail that Hannibal’s fellow general, Himilcar, in order to appease the god’s anger, sacrificed a young boy to Baal Hammon. Subsequently, after suffering a defeat at the hands of the Syracusan army, the Carthaginians managed to retrieve the situation sufficiently that they forced the citizens of Acragas hurriedly to evacuate their city. Diodorus/Timaeus describes how Himilcar and the Carthaginian army then went on a looting session, seizing all manner of works of art and other precious objects from the abandoned temples and mansions. However, this is one of the few occasions when we possess a document–a Punic inscription from the tophet at Carthage–which, although incomplete, provides a Carthaginian view of these events:

And this mtnt at the new moon [of the month] [P] ‘It. year of Ešmunamos son of Adnibaal the i [Great?] and Hanno son of Bodaštart son of Hanno the rb. And the rbm [general] Adnibaal son of Gescon the rb and Himilco son of Hanno the rb went to [H]alaisa. And they seized Agragant [Acragas]. And they established peace with the citizens of Naxos.

Despite the limited nature of the information that it imparts, the inscription stands as an important reminder of how one-sided and partial our usual historical view of these events actually is.

Eventually, in 405, the Carthaginian generals, having lost over half their army to plague but having gained a strategic advantage, offered Syracuse a treaty of peace, which was accepted by their hard-pressed foes. Understandably, the terms were very favourable to the Carthaginians. Their authority over the indigenous and Punic areas of west and central Sicily was recognized, and the payment of an annual tribute to Carthage by a number of cities on the island was ratified.