With the seizure of Crete, Erich Raeder and his naval strategists came to view the Mediterranean, not Russia, as the pivot on which all of Germany’s future aggressions should turn. The lure of Suez and the Middle East now took definite shape. “The appeal of a Mediterranean campaign lay not only in its objectives but in its economy of force.” The critical Battle of the Atlantic could be sustained without interruption, and the continued raiding cruises by German armed merchantmen and battleships would periodically lure Force H away from Gibraltar out into the Atlantic, preventing reinforcement of Cunningham’s meager fleet at Alexandria. German control of the eastern Mediterranean through Greece and Crete provided Hitler the opportunity to pressure Spain’s fascist dictator, Francisco Franco, into allowing German troops and air force units to move through Iberia to seize Gibraltar. Spanish Morocco and the Canary Islands would be taken next, effectively flanking and neutralizing any rebel French forces in North and West Africa. At that point, Admiral Darlan at Algiers, without warships but with an army, might be tempted to throw in his lot with Berlin. “Russia, the timid giant, was to be offered concessions in . . . Iran, Afghanistan, and north-western India as the Germans took the Dardenelles.”

Defense of that vast new area would be based on the Mediterranean— with the unassailable Sahara to the south, fringed by a few heavily fortified ports on the rugged and inhospitable western African shore. To the north an “Atlantic Wall” would be buttressed by mobile forces operating on interior lines in western Europe. Mussolini’s “Mare Nostrum” would become an Axis military and commercial highway, and the lower North Atlantic a baseless and dangerous wasteland for the British.

With Joseph Stalin’s unwillingness to fight except defensively and with all the resources of western Europe concentrated against the British Isles and their supply lines, the chances for forcing British capitulation would have been quite good, especially if Hitler’s demands had been moderate.

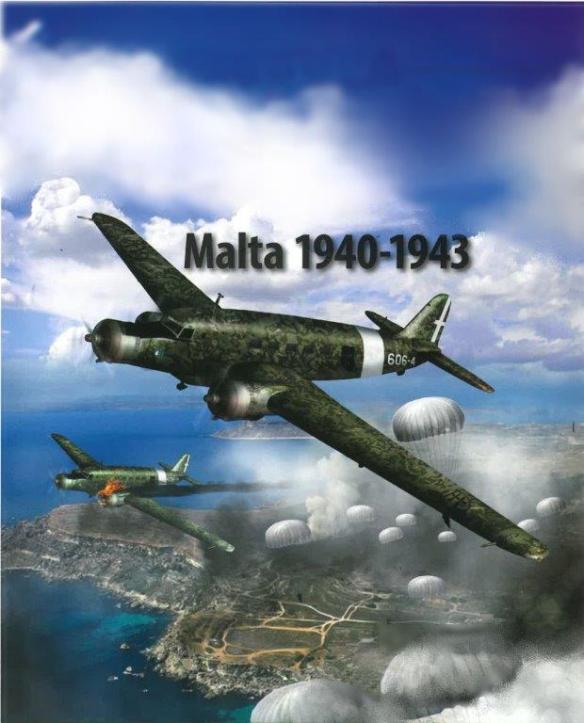

It is clear now as it was to some then that had Hitler “wanted the Middle Sea as badly as he wanted Russia, he could have had it.” By the beginning of 1942, Axis forces occupied not only the entire northern shore but great stretches of the southern shore as well. All that stood between a successful German pincer movement into Palestine and on to the Persian Gulf was the Eighth Army in the Western Desert and Cunningham’s units at Alexandria. For a brief moment Hitler was tempted to grab the prize that was so nearly in his grasp. He and Mussolini together with their respective staffs seriously considered a combined air and sea assault to capture Malta that would have fairly isolated Cunningham at Alexandria from sufficient reinforcement.

By this time the Italian navy had thrown off its cloak of gloom and cowardice. The duce’s sailors bestirred themselves to cooperate closely with the Regia Aeronautica in securing the vital convoy routes to the Italo-German North African front. Daring Italian “frogmen” penetrated Alexandria Harbor in December 1941 to blast and virtually sink the British battleships Queen Elizabeth and Valiant at their moorings, thereby crippling Cunningham’s ability to project power and protect the Malta convoys. They were still run, but by the spring of 1942 Malta was a desperate place to be, as it barely hung on.

Had Operation Herkules been carried out against the island successfully, it would have also precluded the Allied counteroffensive that began in North Africa the following November. American landings inside the Mediterranean would have been impossible given German and Italian air bases on nearby Malta, and the Atlantic beachhead at Casablanca might have been contained. Subsequent Anglo-American assaults on Sicily, Salerno, and Anzio could not have taken place; Italy would doubtless have remained in the war; and the Allies would have never gained the invaluable experiences in mounting combined operations that were an essential prelude to the landings in Normandy. In short, the seizure of Malta might have rendered Germany’s position in the West impregnable.

But the perspective from Berlin between the late springs of 1941 and 1942 did not appear as promising as hindsight would suggest. Despite the marked improvement in his naval and air forces, Mussolini was at best an uncertain and increasingly costly partner. Above all, the British were getting just enough supplies through to Malta to keep the island free and functioning. Through much of its siege, the island remained home to the submarine Tenth Flotilla; its air defenses and bomber forces were never completely destroyed. In November 1941 the Admiralty dispatched to the island Force K—light cruisers Arethusa and Penelope and two destroyers—under the command of Captain W. G. Agnew. The small task force was soon reinforced by other light units and functioned effectively for nearly two months before blundering into the enemy minefield off the North African coast.

Thus, although Malta approached collapse on several occasions—the last as late as the summer of 1942 when outright starvation faced the islanders due to the enemy’s near suppression of convoys from Gibraltar and Alexandria—it never went under. As the crisis approached its climax that May, the Tenth Flotilla was withdrawn to Alexandria. But when the garrison had been strong in previous months, its handful of Wellingtons, Beauforts, Blenheims, Hurricanes, Swordfish, cruisers, destroyers, and submarines were able to massacre several enemy convoys supplying Rommel. In November 1941, “77 per cent of all Rommel’s supplies had been sunk,” and the Eighth Army promptly launched an offensive along the North African shore that drove the Germans back five hundred miles in six weeks. The German General Staff had already concluded after one slaughter the previous September that the situation in the western Mediterranean was “untenable. Italian naval and air forces are incapable of providing adequate cover for the convoys. . . . The Naval Staff considers radical changes and immediate measures to remedy the situation imperative, otherwise . . . the entire Italo-German position in North Africa will be lost.” It was this conclusion that prompted Hitler’s disastrous decision to strip his still small but deadly Atlantic U-boat force of half its active strength in order to destroy the Malta supply convoys. But as desperate as was its eventual plight, Malta would undoubtedly have put up a very stiff and costly fight for survival should Axis forces have ever attempted to seize it.

Hitler’s fatal adventure in Russia precluded such a step. To win the Mediterranean and thereby absolutely secure his southern flank, the führer would have had to postpone Operation Barbarossa indefinitely or, had the Russian campaign already begun, suspend virtually all operations on the vast arc from Leningrad to the Volga. This Hitler was never willing to do. Compared to the lure of the Ukraine and the distant Caucasian oil fields, the Mediterranean held little interest once the great Romanian oil fields at Ploieşti had been protected from British air attacks from Greece. The führer’s essential uninterest and the always growing demands of the Russian front forced Rommel to operate on a shoestring. The Afrika Korps was always weaker and its supplies far less than Allied calculations supposed.

Even if the Russian front had not existed, it is doubtful that the führer would have moved against Malta in the winter or summer of 1942—or against the Canaries and Spanish Morocco the year before. The costly campaign in Crete (General Student’s badly battered German paratroops never again played a major role in the war) reconfirmed Hitler’s long-standing and profound fear of the sea, and Crete had been immediately preceded by the shattering loss of Bismarck. In some way the sea induced in Hitler a feeling he could not abide— the loss of control. Enterprises on and over water apparently possessed for him an inherent uncertainty and instability that did not accrue to land combat. He did make several “feeble” tries at securing his southern flank: strengthening the Luftwaffe in Italy and the Dodecanese in the autumn of 1941 when he believed Russia was on the ropes, ordering Dönitz to virtually close down the Battle of the Atlantic at roughly the same time in order to send German U-boats against both Force H and Cunningham’s fleet, and occasionally devoting attention to getting convoys through to Rommel. But such fitful efforts proved a “no go. Signals inside hemmed him, made him uneasy, unsure,” and he was thus instinctively receptive to Dönitz’s complaints that the Mediterranean was not a decisive theater in which the U-boats could win the war for Germany.

ATTACK PLAN FOR MALTA

It was the spring of 1942 before General der Flieger Student could tackle the task of rebuilding his decimated airborne forces. The first formations were returning from the East, where they had been badly battered. Von der Heydte’s battalion was sent to the Döberitz-Elsgrund Training Area, where it was redesignated as an instructional battalion. Experiments were conducted with night jumps and descents on wooded areas. Efforts were also undertaken to allow the paratroopers to jump with their main small arm instead of having to retrieve one from a weapons container. Trials were also conducted starting in May of that year with a new generation of gliders such as the Gotha Go 242.

There was a purpose to all of those efforts. Von der Heydte’s battalion was earmarked for the initial assault on Malta, where it would jump into the British antiaircraft defenses six hours before the main body arrived and take them out of commission.

The attack plan for Malta and several other operations had recently been discussed in Rome. Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring had summoned Student to Italy’s capital. Student saw Generalmajor Ramcke there as well, as the latter had been sent to Italy to help train that country’s fledgling airborne corps. The airborne division “Folgore” and the air-landed division “Superba” were being formed and trained in accordance with German doctrinal principles.

Together with Ramcke, Student worked out the first draft for an assault on the island fortress. In theory, command and control of the operation was under the Commander-in-Chief of the Italian forces, Colonel General Cavallero. By involving the Italians in this way, the Germans hoped to secure access to all of the Italian fleet to support the operation.

Ramcke and Student came up with an operation that was broken down into four parts:

Part One: After a surprise landing by gliderborne forces from von der Heydte’s battalion on the antiaircraft batteries of Malta and the subsequent elimination of them, the main body of the paratroopers and air-landed forces will arrive as the advance guard under the personal command and control of General Student to the south of La Valetta on the high ground there. It will establish a broad landing zone on the island and attack the airfields and city of La Valetta in rapid, decisive action.

Part Two: Seaborne landings of the main body of the attack forces south of La Valetta, which will advance in conjunction with the airborne forces from that area.

Part Three: In order to deceive the enemy and divert his attention, there will be a deception operation against Marsa Scirocco Bay.

Part Four: The safety of the seaborne transports is the responsibility of the Italian fleet. The securing of the air space is the responsibility of Luftflotte 2. The formations of that tactical air force will conduct massed attacks on the airfields and antiaircraft positions on Malta prior to the airborne landings, defeat the enemy’s air forces and paralyze the enemy’s antiaircraft defenses.

For the operation, 12 of the Gigant transporters were available for planning purposes. The Me 323 had six engines and were able to take a complete Flak platoon or 130 fully loaded soldiers in one lift.

The operations received the codename Unternehmen “Herkules” and lived up to its name, both in size and ambition. The chances for success were good, better than those on Crete had been. The point of debarkation for the identified forces was Sicily. The II. Flieger-Korps of General der Flieger was earmarked to support the airborne forces. In addition, the entire Italian Air Force was designated to support the operations. Mussolini also promised the use of all of the Italian Navy, including its capital ships.

The Italian airborne division “Folgore” was based in Viterbo and Tarquinia and under the command of General Frattini. Thanks to the help received from Ramcke, he was able to imbue the fledging Italian airborne force with true airborne spirit. The air-landed division “Superba” was also a formidable combat formation. In addition, there were four well-equipped Italian infantry divisions to be added to the mix. That was a force that outnumbered the one used to take Crete by many fold.

In the middle of these preparations, a telegram summoned Student to the Führer Headquarters in Rastenburg. Student had just arrived, when Generaloberst Jeschonnek, the new Chief-of-Staff of the Luftwaffe, greeted him with these words: “Listen to me, Student. Tomorrow morning you’ll have a hard audience with the Führer. General der Panzertruppe Crüwell from the Afrika-Korps was just here. With regard to the esprit de corps of the Italian forces, he had delivered a shattering verdict. As a result, the Malta Operation is in danger, since Hitler doubts the resoluteness and devotion of the Italians more than ever.”

Despite that, Student hoped to be able to convince Hitler. In front of a large audience, Student presented the final plans for “Herkules” the next day. Hitler listened attentively and asked a number of questions. When Student finished his presentation, Hitler aired his opinion.

After the war, Student said the following:

A torrent of words flowed from Hitler: “The establishment of one of the bridgeheads with the airborne forces has been assured. But I guarantee you the following: When the attack starts, the British ships at Alexandria will sail out and also those from the British fleet at Gibraltar. Then see what the Italians do: When the first radio messages arrive about the approach of the British naval forces, the Italian fleet will run back to its harbors. The warship and the transporters with the forces to be landed will both head back. And then you’ll be sitting alone with your paratroopers on the island.”

Student was prepared for just such an objection.

He stated: Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring has taken that eventuality into consideration. Then the English will experience what happened to them a year before on Crete when Richthofen came in and sank a portion of the Alexandria squadron. It will probably be even worse for the enemy, since Malta is within the effective range of the Luftwaffe. The air routes to Malta from Sicily are considerably shorter than those from Greece to Crete were. On the other side, the distances for the British naval groups are twice as far as those to Crete. Malta, mein Führer, can thus become the grave of the British Mediterranean Fleet.

Hitler could not make up his mind. With the specter of Crete still haunting him, he vacillated. Malta most certainly should have been a priority in the larger sense, since the British 10th Submarine Fleet operated from the island, which was responsible for sinking so much Axis shipping bound for Africa.

But, in the end, he decided against it, and even Student’s assurances that even in the worst case the airborne forces could take the island all by themselves, because Malta had already been badly battered by the German aerial attacks. In the end, Hitler decided: “The attack against Malta will not take place in 1942.”

As a result of this decision, Hitler cancelled an operation that would have lent an entirely new face to the overall conduct of the war in the Mediterranean and would have decisively influenced the war in Africa in favor of the Germans.