Browning’s briefing

On 10 September, immediately after the cancellation of Operation ‘Comet’, the commanders of the three airborne divisions were summoned to Montgomery’s headquarters to be briefed by Lieutenant General Browning, who was both deputy commander of the 1st Allied Airborne Army and commander of the British Airborne Corps, and in the latter capacity in charge of the planning for Operation `Market’.

When given his orders by Montgomery, Browning was told that the 2nd Army would be up to Arnhem in two days. Feeling some reservation about this optimism he made the reply made famous by Cornelius Ryan’s `best seller’: `We can hold the bridge for four days but I think we may be going a bridge too far’ (editor’s italics).

This reply should not be interpreted to mean that Browning favoured an airborne operation which stopped short after crossing the Waal at Nijmegen. That would have been to forgo the prize of ending the war in 1944 at which the whole operation was aimed, and to have turned a potentially decisive strategic stroke into yet another airborne operation for limited tactical ends, a use to which at this juncture the author feels sure airborne forces would never have been put, for if the Rhine was not to be `bounced’ the 2nd Army would surely have been directed to clearing the estuary of the Scheldt, opening up the port of Antwerp.

The concept of ‘a bridge too far’ meant That the Allies were paying the penalty for not having a strong advocate of the strategic use of airborne forces at sufficiently high level of command to ensure that when the opportunity arose, those forces were adequate to seize it. The belated formation of the 1st Allied Airborne Army, a planning organization outside the normal chain of command and planning, was no answer.

Too little airlift

The problem of making a success of ‘Market‑Garden’ was not that there were too many bridges but rather too little airlift. This meant, as will become clear, that the 1st Airborne Division’s plan had of necessity to run counter to the two most important principles of airborne operations: the achievement of surprise and concentration of force. Had it been possible to put the 1st Airborne Division down in one lift success would almost certainly have been assured; had it been possible to use a fourth airborne division success could have been guaranteed, for in the planning it had been recognized that it was unlikely that the US 82nd Airborne Division would be able to take the Nijmegen bridge as well as the bridge at Grave and the vital high ground south of the Waal and east of Nijmegen. This proved correct and when the Guards Armoured Division reached Nijmegen the carpet had yet to be extended beyond the Waal.

American advantages

The shortage of airlift capacity presented the corps planners with a problem. While the 1st Airborne Division was clearly going to be in the most exposed position and would need to hold out the longest, to deprive the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions of the necessary forces to capture the bridges which alone would ensure their timely relief by XXX Corps would be doing them no service.

In the end the allocation of aircraft to divisions was as follows: 481 to the 1st Airborne; 530 to the 82nd Airborne; 494 to the 101st Airborne; and 38 to the Airborne Corps headquarters. All the aircraft allotted to the American divisions were American‑piloted Douglas C‑47s. The British lift was made up of 149 American and 130 RAF C‑47s, and 494 converted RAF bombers, mostly four‑engined. Although the 1st Airborne Division had fewer aircraft, the capacity of their Horsa and Hamilcar gliders gave them a larger lift in men or tons of equipment.

This allocation meant that each division could fly in only about two‑thirds of its strength with the first lift ‑ in the case of the 1st Airborne Division, which had the Polish Parachute Brigade under command, only half. To reduce this handicap as much as possible, the soldiers pressed for two lifts on the first day but this was turned down mainly because there was no moon and the American pilots were not considered to have the capability of carrying out airborne operations at night under these conditions.

As soon as Urquhart had received his orders, planning for ‘Market’ started in the stately club house at Moor Park which was the headquarters of the British Airborne Corps and the tactical headquarters and briefing centre for the 1st Airborne Division when operations were in course of preparation. Units of the 1st Airborne Division and the Polish Parachute Brigade remained at their airfield assembly camps after being stood down from Operation `Comet’. The division’s administrative tail with, among other things, personal kit had already crossed to the continent by sea.

Triple tasks

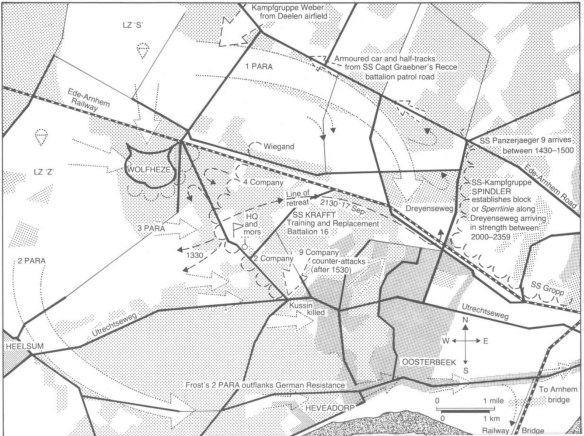

General Urquhart translated the divisional aim into three tasks. The primary task was to capture the Arnhem bridges or a bridge; the secondary task was to establish a sufficient bridgehead to enable the follow‑up formations of XXX Corps to deploy north of the Neder Rijn; lastly, during operations immediately following the landing of the first lift, everything was to be done to ensure the safe passage of subsequent lifts by destroying antiaircraft positions in the vicinity of the dropping and landing zones and of Arnhem.

To accomplish these tasks the battle experienced 1st Parachute Brigade, under Brigadier Gerald Lathbury, was given the job of seizing the rail and road bridges at Arnhem. The 4th Parachute Brigade, under Brigadier ‘Shan’ Hackett, was to occupy the high ground on the northern outskirts of Arnhem with the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade, under Major‑General Stanislaw Sosabowski, holding the eastern perimeter, and the 1st Airlanding Brigade, under Brigadier ‘Pip’ Hicks, the western.

But what of the enemy? Ever since a, fortunately abortive, plan to drop the 1st Airborne Division in the Orleans gap in the path of German armour escaping from the Falaise‑Argentan pocket, the redoubtable and experienced commander of the Polish Parachute Brigade, which first came under command of the 1st Airborne Division for that operation, showed a good deal more concern about enemy strengths and dispositions than did the British. His realism in this has rightly been praised, but it was also coloured by a strong desire not to get his brigade pinned down in western Europe, for he was dedicated to the liberation of Warsaw. The British 1st Airborne Division, on the other number of anti‑tank guns should on no hand, had a natural tendency to play down the enemy in its intense desire to get into battle.

The expectation at the time of ‘Market-Garden’ was that, though German resistance on the Meuse‑Escaut Canal was stiffening, it was expected that once that crust was broken, there would be little to hold up the advance of XXX Corps. The airborne divisional commanders were led to expect no more opposition, pat most, than a brigade of German infantry with a handful of tanks. Reports of German armour re‑forming in the vicinity of Arnhem began to come through from 10 September onwards, but though these were taken seriously by the intelligence staff they were largely discounted by commanders.

Poles in reserve

Intelligence suggesting that the Germans were beginning to recover from their crushing defeat in Normandy and that stronger resistance might be expected was not allowed to influence the operational account be reduced, when the quantity of aircraft allotted to the division’s first lift was cut.

On the other hand, reports that there had been a 30 per cent build‑up in the German anti‑aircraft defences around Arnhem and the Deelen airfield, north of the city, were taken very seriously by the RAF. It ruled out all thought of a coup‑de-main by gliders on the bridges and led to a disagreement between Air Vice‑Marshal Leslie Hollinghurst, air officer commanding No 38 Group RAF and responsible for the 1st Airborne Division’s air movement plan, and Urquhart as to the position of the dropping and landing zones.

Urquhart was prepared to accept the dry heathland some 7 miles (1125km) west of Arnhem for the mass glider landing, but he pressed Hollinghurst hard to drop the 1st Parachute Brigade on both sides of the river and as near to the Arnhem bridges as possible. The RAF, however, believed that to do so would invite unacceptable losses and it was decided that the drop should take place in the same area as the glider landing but with different zones.

This decision seriously prejudiced the tactical success of the division. Short of airlift, members of the division begrudged the 38 glider loads allotted to the Airborne Corps HQ, for this already meant that only half Urquhart’s command would be available to exploit the initial surprise. On top of that the decision to drop and land 7 miles (11~25km) from the objective again divided the remaining forces as one brigade would be needed to hold the DZs and LZs until the second lift came in, leaving only one brigade to go for the Arnhem bridges.

Intelligence ignored

It was decided that the 1st Parachute Brigade would on landing go for the final objective, the bridges, leaving the 1st Airlanding Brigade to guard the landing area until the fly-in of the 4th Polish Brigade on D+1. The Polish brigade would be held in reserve with the expected role of being dropped immediately south of the Arnhem road bridge on D+2, provided that the anti-aircraft fire covering the area around the bridge had been eliminated. A landing zone east of the main divisional landing zone had been selected for the gliderborne portion of the Polish brigade due to land on D+2.

This plan, forced on the 1st Airborne Division’s commander by circumstances, ran counter to the principles of war of greatest importance in airborne operations surprise and concentration of force. These required that the force be landed on or as near as possible to their objective, taking into account enemy strength and dispositions. The plan as it stood was a perfect receipt for defeat in detail.

The author has heard General Jim Gavin, the dynamic commander of the American 82nd Airborne Division, say that the British should have been prepared to accept a 10 per cent increase in casualties in order to land nearer their objectives. He was, however, unaware that the RAF had at the briefing at Moor Park, predicted up to 40 per cent casualties on the fly‑in according to the adopted plan. Urquhart can hardly be expected to have suggested making it 50 per; cent.

Divided command

In any case there was no way in which Urquhart could have influenced the RAF plan except by persuasion, the War Office and the Air Ministry having formally agreed that ‘Airborne operations are air operations and should he entirely controlled by the Air Commander‑in‑Chief.’ Why then, ask some critics, did Urquhart not refuse to go’.?

The author believes there were two fundamental reasons. Firstly, given the correctness of higher commands’ estimate of the strength and condition of the enemy, and given that all went according to plan, then despite the plan’s very serious weaknesses there was still a reasonable chance of success, and success held out the best hope of ending the war in 1944. In these circumstances it would not seem reasonable to expect the 1st Airborne Division’s commander to refuse to carry out his superiors’ orders.

There was, however, a second reason which those who were not directly involved may find difficult to comprehend. The morale of the 1st Airborne Division was high, but it had become increasingly brittle as a result of the frustration felt from planning and getting ready for 16 abortive operations. Officers and men had joined airborne forces to see action in novel and exciting circumstances, but instead they had been held back on the side lines, spectators while others fought.

Limited experience

There were units in the division that had seen hard fighting in North Africa and Sicily but a considerable part of the division had only seen limited action in Italy and some none at all. In September it looked as if the war would be over without their having heard a shot fired in anger, let alone demonstrated the élan which had come to be associated with the Red Beret. It is significant that when the RAF predicted up to 40 per cent casualties on the fly‑in, no one appeared to be listening. In these circumstances another cancellation would most probably have destroyed the division’s morale, it would certainly have destroyed the acceptance of Urquhart’s leadership.

As we now know, things did not go according to plan, nor was luck on the side of the 1st Airborne Division. Before turning to a broad consideration of the `Market Garden’ operation as events unfolded, attention should be drawn to one more serious weakness from which the 1st Airhorne Division suffered and which, like others, stemmed largely from the failure at the highest levels of command to appreciate the strategic potential of airborne forces and the organization and equipment required to exploit it.

Light artillery only

The organic artillery of an airborne division was strictly limited by the airlift required for carrying guns and ammunition, particularly the latter. The 1st Airborne Division’s field artillery consisted of only 24 75mm pack howitzers, firing 151b (6‑8kg) shells, and organized into three batteries, each affiliated to one of the brigades. For the 1st Parachute Brigade’s operation in Sicily, ad hoc arrangements were made to enable an airborne gunner officer to control the fire of the artillery of the link‑up forces as they came within range, so no field artillery accompanied the brigade.

Between Sicily and the Normandy invasion the Royal Artillery paid great attention to this problem, and the two British airborne divisions were each supplied with a FOURA (Forward Observation Unit, Royal Artillery) made up of officers with signallers and wireless sets designed to control the fire of the link‑up artillery and supplement the limited number of OP parties the divisional artillery ‑regiment could provide.

When airborne forces were used tactically in close support of the ground forces, these arrangements were adequate as the airborne forces either landed within range of the longer‑ranged link‑up artillery or would become so very soon after landing. In a strategic role, such as that of the 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem, it must be expected that a considerable time would elapse before the fire of the divisional artillery regiment could be supplemented by that of artillery from outside the division. Daring this time tit, division would be heavily dependent for close fire‑support on the air forces. One of the unanswered questions about the Arnhem operations is why the arrangements for close air support were so inadequate.

The need had long been recognized and shortly after the Normandy landings a staff officer from divisional headquarters was sent over to study the problem at first hand but no ASSU (Air Support Signal Unit) was developed. In consequence the arrangements for ground to air communications for the support of the 1st Airborne Division had to be improvised. The normal British wireless set used by an ASSU for ground‑to‑air communications was not airportable. The Americans had a set that could be carried in a British General Aircraft Hamilcar or American Waco CG‑4A glider. Unfortunately one of the two sets allotted to the 1st Airborne Division was damaged on landing and no more than one contact was made with the other. The American signallers who accompanied the sets were unfamiliar with them and untrained in operating ground-to‑air communications.

No air support

No 83 Group RAF was responsible for providing the 1st Airborne Division with close air support. In this, apart from the failure of the ground to air communications, the group was severely handicapped by fog over its airfields most mornings and by their aircraft being kept out of the area whenever aircraft of the US 8th Air Force were providing fighter cover for the air transport force bringing in troops or supplies. In consequence, not only were the airborne forces largely deprived of close air support, but also of the salutary effect which the continual presence of Allied aircraft overhead would have had on enemy morale. It was an admitted serious error that all aircraft flying in the battle area had not been placed under the control of the local air. commander, the air officer commanding No 83 Group, with a senior liaison officer having direct communications with the 8th USAAF at his headquarters.

Having cleared out of the way some of the structural weaknesses and inadequacies which militated against the effective use of airborne forces in a strategic role, let us turn our attention to the development of events.

It was decided that Operation ‘Market Garden’ would start on Sunday 17 September, and that the airborne drop and glider landings would take place at about the same time for all three airborne divisions: the 1st Airborne Division at 1250, with the Independent Parachute Company responsible for marking the dropping and landing zones dropped 20 minutes ahead of the main body; and the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions at 1230.

RAF fears

A second lift was to go in on 18 September, with the first arrivals at 1000. This lift was held up by bad weather, and finally came in four hours late. For the 1st and 82nd Airborne Divisions there was to be an important third lift on D + 2, bringing in the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade and 325th Glider Infantry Regimental Combat Team for the British and Americans respectively. In all, some 34,000 troops were flown in, 20,190 being dropped by parachute and 13,781 landed by glider: of the paratroopers 16,500 dropped on 1 7 September.

As noted already, the RAF believed that the build‑up of German anti‑aircraft defences on barges as well as on land presented a serious threat to the vulnerable air transport trains. To reduce this to a minimum 821 Boeing B‑17s of the 8th UBAAF dropped 3,139 tons of bombs on 117 sites, Bomber Command attacked German fighter airfields during the night of 16-17 September, and in daylight raids against coastal batteries in the Walcheren area 85 Avro Lancasters and 15 de Havilland Mosquitoes dropped 535 tons of bombs.

The air trains were provided with escort and anti‑flak patrols by 550 8th USAAF Lockheed P‑38 Lightnings, Republic P‑47 Thunderbolts and North American P‑51 Mustangs, and by 371 Hawker Tempests, Supermarine Spitfires and de Havilland Mosquitoes of the Air Defence of Great Britain command, while 166 fighters of the US 9th Air Force gave umbrella cover over the dropping and landing zones.

No concentration

Early on 17 September 84 Mosquitoes, Douglas Bostons and North American Mitchells of the 2nd TAF attacked barracks in Nijmegen, Cleve, Arnhem and Ede. That evening dummy parachute drops were made west of Utrecht, and east of Nijmegen and Emmerich.

Splitting the airborne forces into two or more lifts not only ran counter to the principle of concentration but made the whole operation hostage to the weather, forecast as good for the whole period of the operations. The weather over Holland on 17 September was excellent, though low cloud over England caused some gliders of the 1st Airborne Division to run into slip‑stream trouble and mainly for this reason 24 of those in the first lift parted company with their tug aircraft over England.

The aerial armada of transport and tug aircraft took off from two groups of airfields. The southern group, mainly in Wiltshire and Oxfordshire, comprised eight British and six American airfields; the eastern group, in Lincolnshire, eight American airfields. The armada crossed the channel in two streams, each stream being divided into three sub‑streams 1‑25 miles (2km) apart.

Brigadier W.F.K Thompson CO of the 1st Airlanding Light Regiment, Royal Artillery with 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem.