On 23 December 1st Lt. Bruno J. Rolak returned to the 1st Battalion CP from leave in Paris and learned to his horror what had happened to his company and battalion at Cheneux. Although the need for an acting executive officer in C Company was urgent, Rolak did not return to his C Company platoon but transferred to B Company. That morning orders came through for the 2nd Battalion to move out. Captain Campana recalled that “the destination turned out to be the town of Lierneux, where we were attached to the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel Billingslea. The battalion was placed in division reserve on the high ground some 5000 yards southwest of Lierneux. The 325th Glider Infantry CP was located in the town of Verleumont on the high ground southeast of Lierneux. This move was part of the division plan to hold the Lierneux ridge since it dominated the road nests at Regne, Fraiture and Hebronval.

“The [2nd] Battalion of the 325th Glider Regiment, which was originally in reserve, had been returned to its mother unit when division orders had required the regiment to further extend its right flank to include Regne and Fraiture. This extension was necessitated by the failure of the 3rd Armored Division on the right flank to maintain physical contact with the 82nd Airborne Division. It was imperative for all the airborne units, in keeping with orders from XVIII Airborne Corps, that contact be made and maintained with American units in the Vielsalm–St. Vith area and provide an exit for their extrication. […]

“The 2nd Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry immediately prepared and occupied defensive positions astride the Regne–Lierneux road. The battalion CP and aid stations were located in two adjacent houses about 800 yards to the rear. Shortly afterwards, the battalion commander and I went to the CP of the 325th Glider Regiment for instructions. While there, we heard reports over the radio stating that 7th Armored Division tanks were still coming through the road blocks.

“That afternoon, 23 December, the enemy attacked and captured the town of Regne. The division commander immediately ordered the recapture of the town, which was accomplished by the 325th Glider Regiment with the aid of supporting armor. During the recapture of Regne, the regimental adjutant of the 2nd SS-Panzer Division was captured with orders for the advance of the following day. These orders were quickly relayed to higher headquarters. That same afternoon, the important crossroads at Fraiture were taken by the enemy.

“Just before dusk that afternoon, the 2nd Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry was ordered to retake the [Baraque de Fraiture] crossroads at Fraiture [where elements of the 2nd SS-Panzer Division had overwhelmed F Company, 325th, in the afternoon]. An artillery liaison officer from the 320th Glider Field Artillery Battalion came down to the CP but could not promise us any artillery support, except possibly from corps artillery. At this time all division artillery was busily engaged along the 25,000-yard sector which was then being held by the division. Thus, without artillery support and without armor, the battalion moved out at 1930 hours to recapture a terrain being held by an enemy superior in numbers and fire power. The only prior reconnaissance made was from a map. The outlook was very black indeed, and the battalion commander had accordingly designated his succession of command before we moved out.”

First Lieutenant Garrison, 2nd Battalion S-1, recalled Colonel Tucker attended the company commanders’ briefing “that Wellems had called to explain the particulars of the attack. We gathered around a table with a spread-out map that Colonel Tucker poked at vaguely. Logic quickly made us realize that the project was deadly. The battalion was to go down a slope near Trois Ponts to a draw that led to a stream in the woods, where Germans were certain to be entrenched. Discussion failed to make the proposal any more palatable than an inevitable trap.

“After Colonel Tucker left, the gathering tried without success to arrive at a less pessimistic interpretation. Eventually, Wellems made assignments. I was to be in charge of the battalion headquarters in the house, of communications, and of response to emergencies. I would have a phone line to regimental headquarters and radio contact with Wellems. Before closing the meeting, he asked, ‘Any questions?’ I did not have essential information that he had several times delayed in giving me—in emergency, who succeeded whom; so I had to ask, ‘What is the chain of command?’ Wellems gave me a hard stare. Concentrating on the matter, he named two officers.

“At the designated time, the battalion led by Wellems started down the snowy hill. He must almost have reached the danger area when I had a call from regiment to cancel the attack because Montgomery had changed his mind. I yelped to the radio operator to get Wellems. Through disruptive static, the far operator finally responded and quickly put Wellems on. The connection was barely clear enough for him to hear, ‘Turn back!’”

When the call came, Lieutenant Colonel Wellems was already in Fraiture, having preceded his battalion to contact the 325th GIR. Moving out with the battalion column, Captain Campana recalled that “suddenly Major [William] Colville, the executive officer, received a radio message stating that the attack had been called off. I suggested that this message be authenticated before adopting any action whatsoever. This was done. The message was from the battalion commander announcing that the attack had definitely been cancelled. The entire battalion did an about-face and returned to Lierneux much happier.”

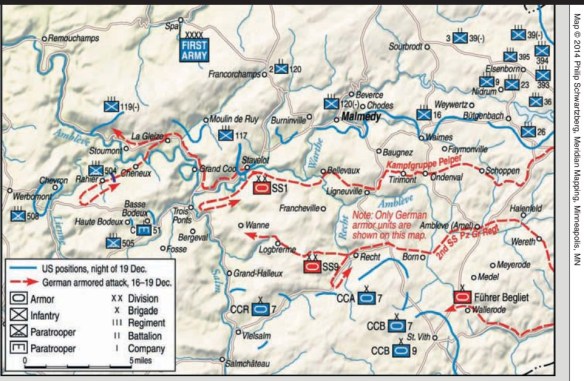

The recall of the attack order for the 2nd Battalion was decided by British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, whose 21st Army Group had temporarily received command responsibility over the U.S. First Army a few days earlier. Montgomery had ordered Major-General Ridgway to withdraw from St. Vith on December 22, and to shorten the defensive lines on the northern side of the German pocket—or bulge—in the Ardennes. As Ridgway’s biographer Clay Blair explains: “Early that evening—December 23—Ridgway took a drastic step of ordering all the forces withdrawing from St. Vith to immediately regroup on his southern front near Manhay. Hasbrouck’s full 7th Armored Division, plus the 424th Infantry Regiment, would block the highway at Manhay. Bill Hoge’s CCB, plus the 112th Infantry Regiment, would be attached directly to Gavin’s 82nd Division at Malempré.”

In the evening another group of replacements was assigned to B Company on the Salm River. One of them, 21-year-old S/Sgt. William L. (“Bill”) Bonning of Hazel Park, Michigan, was among those taken to 2nd Lt. Douglass’ 3rd Platoon. Born in Hazel Park near Detroit, in December 1922, Bonning entered the service in Royal Oak, Michigan, as a 20-year-old draftee in January 1943. Wanting to choose his own branch of the U.S. Army after basic training, he opted for the paratroopers but was turned down twice because he was two inches shorter than the 5 foot 6 inch minimum.

The third time he attempted to get in, luck was with him. Recognizing Bonning, a medic tossed him a handful of matchbooks to put in his socks to lift his feet up. The trick worked: he began jump training at Fort Benning, Georgia, in August 1944, and was shipped to Europe in the fall with the rank of staff sergeant.

Along with a few others, Bonning was brought to the 3rd Platoon CP where “they introduced me to Lieutenant Douglass. He looked a lot younger than me. I said, ‘You have to be kidding.’ I thought they were making a joke. It was night time when we were assigned. Lieutenant Douglass didn’t appreciate my remark and I got admonished.” Surprisingly, no one told Bonning the name of the company commander: “You learned the name of your company commander after a few weeks. Basically you were with your platoon most of the time.” Veterans of the 504th did not like it when high-ranking non-commissioned officers came in with the replacements from parachute school, because they had no combat experience but were required to lead at least a rifle squad. It also meant that promotions that had been in the offing were frozen until new vacancies in the cadre were created. In Bonning’s case, it was only a few weeks before they found some reason to demote him to private, but he eventually earned his stripes back.

The 3rd Battalion found several red-colored parachute equipment bundles on December 23 that later transpired to be from a German resupply drop for Kampfgruppe Peiper. The supplies unfortunately added nothing to the battalion’s meager K-rations, since they consisted of gasoline and 88mm ammunition.

At 1130 hours a patrol of I Company was dispatched to contact the 119th Infantry Regiment south of the Château de Froidcour. They returned at 1400 hours to report the exact location of that regiment. At the same time a call came into the 3rd Battalion CP from 1st Lieutenant Megellas of H Company, who had spotted a German crew setting up an 88mm gun. Artillery was called in, but XVIII Airborne Corps vetoed artillery fire on the gun later that afternoon. Nothing remained than to try it with 1st Lt. Allen F. McClain’s 81mm Mortar Platoon. When the gun unfortunately appeared to be out of range, the 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion was called in and fired a few shells, but the forward observer was not sure if they scored a direct hit or not. Another three-man contact patrol sent out to check on the 119th Infantry at dusk returned at 1900 hours with the news that the 119th had been stopped by tanks and infantry and was still in the same position.

Meanwhile Obersturmbannführer Jochen Peiper decided to pull his forces out that night. Leaving approximately 50 of his remaining 850 officers and men as a rear guard to disable his remaining vehicles, he withdrew with the rest of his men and a few unwounded American prisoners. Conditions could not have been better as he withdrew across the La Venn bridges on the Amblève River in a southern direction, searching for a bridge across the Salm River to move east. First, it had begun to snow and frost, creating a perfect natural cover in the dark. Second, by moving the 2nd Battalion to Fraiture in the afternoon, Major General Gavin had seriously thinned 504th defensive lines. These now stretched all the way from Rahier to Cheneux, Monceau, Brume and on to Trois Ponts through heavily wooded terrain, the screening of which called for two battalions at full strength.

Peiper recalled that his “forces started breaking out of the pocket during the night of 24 December at about 0200 hours, after all armored vehicles had been blown up. Without encountering resistance, the Kampfgruppe moved southward from La Gleize via La Gleize railway station, crossed the Amblève valley over a small bridge, and in a long, drawn-out column reached the wooded area west of Trois Ponts under most difficult conditions.”

In the early morning of December 24, the 3rd Battalion was alerted to break up as soon as possible for a truck ride to Jevigné, almost two dozen miles southwest of Cheneux. The 30th was expanding its sector, and the 82nd was pulling back to a shorter defensive line. At 0940 hours the 3rd Battalion cleared Cheneux, arriving in Jevigné at 1030 hours. Second Lieutenant George A. Amos of Weston, Illinois, a recently assigned platoon leader in I Company, earned a Silver Star “while leading his platoon on a reconnaissance for a road block position, [where] two enemy machine guns and several riflemen unexpectedly opened fire on the platoon. With utter disregard for his own safety, Second Lieutenant Amos single-handedly charged the nearest machine-gun nest, killing the four occupants with his submachine gun. From this position he delivered a withering fire, knocking out the other machine gun and forcing the remaining enemy to withdraw from a vital spot, thus enabling the platoon to accomplish its mission.” Despite Amos’bravery, Pvt. Donald W. Johnson was killed and several others were wounded. Cut off from the remainder of the company, Amos’ platoon set up a road block and was on its own for several hours. Only when G Company was sent in with a sweeping move to clear the area, did I Company manage to link up with the platoon and drove the Germans back.

Captain Campana recalled that “late in the afternoon of 24 December, the 2nd [Battalion] was informed that the 82nd Airborne Division had been ordered to withdraw to a new and shorter defensive position eight miles to the rear. Each unit was ordered to leave a covering force equivalent to one third the size of the unit. This covering force would remain in position until 0400 hours on 25 December and would then return by truck to the new defensive positions. Accordingly, one platoon from each rifle company was left behind with Lieutenant Fust, Battalion S-2, designated as covering force commander for our battalion.

“Just after dusk, 24 December, the battalion minus the covering force started its withdrawal. I and the executive officer were not informed of the location of the new defense positions, nor were they informed of the route to be followed to the rear. Christmas Eve was a very cold, bright, moonlit night. Along the route, we saw evidence of prepared demolitions and road obstacles executed by our engineers. For the most part, the withdrawal was accomplished without any difficulty, except in the sector to the north where the 505th and 508th Parachute Regiments were constantly being harassed by a very persistent foe.”

Sergeant Mitchell E. Rech of A Company spent Christmas Eve singing Christmas Carols in Trois Ponts: “My buddies [Pfc.] Roger (“Frenchy”) Lambert and [T/5] Les Lucas and I were singing Christmas carols aided by a bottle of wine. New snow on the ground, moonlit night. The Germans did not appreciate good singing and gave us a few rounds of mortars. They missed, but we got the hint.”

A Company was still holding its position at Trois Ponts along the Amblève River, unaware of the plan to withdraw the entire division. The 1st Battalion was defending a front from Trois Ponts in the south to D Company in Cheneux with the order to hold their ground against any new German attack. But there would be no other attack—the 1st SS-Panzer Division was unable to reach the encircled remnants of Kampfgruppe Peiper at La Gleize.

Peiper led his 800 men behind B Company that night and moved on to Bergeval, where in the confusion of a firefight, his foremost prisoner, Maj. Hal McCown, 119th Infantry Regiment, managed to escape. At Rochelinval Peiper’s depleted force swam “across the icy and turbulent Salm River, [and] broke through the American front. Contact with German advance elements was established only in Wanne, six kilometers east of the American positions in the Salm Valley.” The remaining covering detachment at La Gleize had meanwhile been overwhelmed: Kampfgruppe Peiper was disbanded, its mission a failure. Only 770 officers and men came through the American lines.

First Lieutenant Breard, the 1st Platoon, B Company commander, describes the action on the “freezing cold” night when Peiper’s men passed his sector near Trois Ponts. “At Christmas Eve our mortars behind the CP were infiltrated and a firefight started. They had 800 men and went down in several positions and came through us. We didn’t know who it was. […] No casualties occurred. […] B Company left that position after midnight and marched through Trois Ponts passing Basse-Bodeaux, where we were finally shuttled to Bra by truck. We went into position just south on the road to Manhay. First Battalion was in reserve near Hill 463. It had started snowing when we left our position on the Salm.”

At 2000 hours 3rd Battalion company commanders gathered in the CP, where Lieutenant Colonel Cook informed them of the decision to withdraw to a new defensive position in the small village of Bra-sur-Lienne, several miles to the northwest. The 2nd Battalion would be on their left flank as far as the next hamlet of Bergifaz with an outpost at Floret, and the battered 1st Battalion would be in regimental reserve. Colonel Billingslea’s 325th GIR would tie in on their right flank. One rifle platoon was to act as a shell while G Company rejoined the battalion. By 0045 hours on December 25 the move had been successfully carried out and the new CP was set up in Bra.

Relieved during the night from its positions along the Amblève River, Major Berry’s unit also made its way to Bra. “Finally, just after dawn on Christmas Day we came to a little village with a church and a few farmhouses,” Private First Class Bayley recalled. “The villagers had awakened to find paratroopers swarming through their village. They feared for the worst and were gathering belongings together and fleeing the area with wagons, carts and bicycles, but no powered vehicles. We saw no sign of their owning any cars or trucks. We never knew where they went, but in a few minutes the village was completely evacuated of civilians. It was sad to see this, but they did this for their own safety, as they did not know what was going to happen.”

The villagers, however, did not depart of their own free will, but on orders to evacuate because their town was now on the front line. Division headquarters had been established in the Chateau Naveau de Bra-sur-Lienne in the center of the village, but had moved out to the northwest during the night. Colonel Tucker in turn made the chateau his regimental headquarters. “I well remember the spooky Christmas Eve at the 504th headquarters when the regiment was withdrawing on Montgomery’s orders from the salient we occupied,” recalled Capt. Frank D. Boyd, an attached officer of the 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion. “The 307th Engineers were blowing bridges behind us and left us only one over which to withdraw. We had orders to retire to Bra and Colonel Tucker asked a Belgian civilian if there was a landmark building in Bra that was easy to identify and find. The man told him there was a big, well-known chateau on the east edge of town and Colonel Tucker said, ‘That is my CP.’”

It was clear to the paratroopers of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, and C Company of the 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion that they were to hold their defensive positions at all costs. They had given ground on orders—but not in battle.