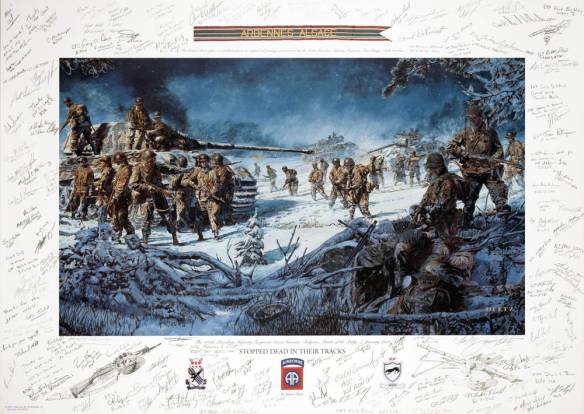

James Dietz prints

CHENEUX AND TROIS PONTS, BELGIUM, DECEMBER 22–24, 1944

During the night of December 21–22, a higher-level G-2 report was telephoned in from 82nd Airborne Division Headquarters stating that the U.S. 7th Armored Division had been heavily attacked late that afternoon and pushed out of the Belgian city of St. Vith to the east. A serious accident occurred later that morning when Lieutenant Colonel Harrison broke his jaw when an American truck crashed into his jeep in Cheneux. The injured battalion commander was sent to an aid post and then evacuated to the rear. His loss was another blow to the remaining 1st Battalion members who had recently lost so many others. It seemed almost unbelievable that the officer who had encouraged his men in the attack on Cheneux from his forward command post, who had crossed the Waal River with them under enemy fire in broad daylight, and who had parachuted into Normandy on D-Day had been put out of commission by a traffic accident.

Major Berry, executive battalion commander, succeeded Lieutenant Colonel Harrison as commanding officer. Captain Milloy of Headquarters Company became acting battalion executive officer, being the most senior officer present. He was not only the youngest company commander, but also the most experienced, having led C Company in all previous campaigns. Major Berry learned at the same time that more replacements were on the way, and would arrive the next day. Milloy was temporarily replaced as company commander by 1st Lieutenant Peyton C. Hartley.

It was difficult for the officers and men of A Company who had moved to Trois Ponts to take in the fact that they had seen no action, whereas many other units in the division had been committed in heavy fighting. Their first casualty was sustained when a sergeant was wounded in a German shelling that morning. “When our house was hit by German cannon fire we ran to a house with a back having open land for about 25 to 30 feet to the river front and settled in there,” recalled Private First Class Bayley. “Our houses were just to the north of the town center on the west bank. This was a very quiet area, nothing happening. A few hundred yards to the north of us and a few hundred yards to the south, some of the most vicious fighting of the war was taking place and would extend over the next several days. We could hear some of it, especially the tank and artillery shells, but nothing was coming into our area and there were no engaged firefights. Germans on the other side of the river were keeping out of sight, as we were on our side.

“It was strangely quiet. It is hard to realize that such quiet could occur on an extremely active battle front. We posted lookouts in the upstairs rooms, being careful to keep away from the windows. During the night the platoon members would take observation turns in a foxhole at the back left-corner of the house. We had our rifles and some very powerful plastic Gammon grenades on the front lip of our foxhole to warn the soldiers if an attack was started. We never had to use them.

“We had our first snow the night of the 22nd. I made my bed in a concrete-constructed coal bin. I don’t know why it seemed safer, but it did. This quiet state of affairs went on through the 24th and was apparently going to last into Christmas Day.”

In the early afternoon, heavy German artillery fire rained down on the 3rd Battalion positions at 1330 hours, appearing to come from the direction of the Château de Froidcour on the other bank of the Amblève River. Fifteen minutes later, 3rd Platoon, I Company, paratroopers sighted a white bed sheet hanging out one of the windows of the château. Captain Burriss sent out a contact patrol to investigate, led by 1st Lt. Harold E. Reeves. According to his Silver Star Citation, Reeves “volunteered to lead a combat patrol with the mission of trying to make contact with friendly troops that had been cut off by the German offensive. First Lieutenant Reeves led his patrol through two miles of enemy-held territory under heavy shelling by the enemy and our own artillery. First Lieutenant Reeves pressed his patrol on through all this until contact was established with friendly troops. As a result of this action, First Lieutenant Reeves’ patrol captured 50 Germans and liberated eight American soldiers that had been captured by the Germans a few days before. Information gained by First Lieutenant Reeves as to the location of Allied Prisoners of War and the enemy troops was invaluable in the attack that was launched shortly on his return.”

As 30th Infantry and 82nd Airborne artillery hammered Kampfgruppe Peiper all day long in La Gleize, some of the shells landed in I Company’s position, but fortunately did not hit anyone. At 1650 hours Lieutenant Reeves’ group reported at back to the 3rd Battalion CP. Reeves informed Lieutenant Colonel Cook that there were both American and German wounded at the Château de Froidcour, and delivered a slightly wounded soldier from the 2nd Armored Division who had returned with them.

“On the afternoon of 22 December,” recalled Captain Campana, “the 2nd Battalion was ordered to relieve the 1st Battalion at Cheneux. On arriving in the town, we saw evidence of the bitter fight which had taken place. German dead and equipment lay strewn on the main road and adjacent fields. A disabled self-propelled gun and tank were on the road. Some of the enemy dead were clad in American olive-drab shirts and wool-knit sweaters beneath their uniforms. The battalion took over the defense of the town and bridge and waited for events to happen. Sounds of brisk fighting on our left flank could be heard, intermingled with tank-gun fire. It was the 119th Infantry attacking the Germans in La Gleize with assistance from the 740th Tank Battalion.”

While Captain Komosa’s D Company occupied positions in Cheneux itself, cameramen filmed their reception by Chaplain Kozak on the western outskirts of the town. As the Catholic chaplain prayed with several troopers clustered around him, a platoon radio operator stood behind him, looking sideways into the camera, smiling feebly. Captain Norman’s E Company took up positions just north of Cheneux; to the south, the battered remnants of C Company were emplaced along the Salm River with B Company to their south, followed by A Company in the northern outskirts of Trois Ponts.

Early in the evening, 1st Lt. Thompson, the 3rd Platoon leader in E Company, was ordered to send out a security patrol to the east to screen the vicinity of La Gleize and find the position of the new German lines. Pvt. George H. Mahon describes the five-man patrol: “I walked down in the middle of a street, two men on either side of me. Our mission was not to get into a skirmish but just to locate [the Germans] and get back. First thing I know, I was looking at a wooded area and I saw a flicker like a cigarette. About the same time I saw a concussion grenade go off in front of me. It blew me down and my helmet was blown off. [No one was hit.] We got up and got back to our lines.”

Around 2045 hours the patrol reported to Lieutenant Thompson that they had heard vehicular movement in the town of La Gleize. During this debriefing, Thompson noticed that Mahon was hobbling: “By the time I got near our lines I couldn’t bend one knee. I told Lieutenant Thompson and he said I should go see the doctors. I said, ‘It’s just swollen from the concussion. It wasn’t a fragmentation grenade. I’ll be all right.’ It was about 2300 hours at night. He told me, ‘Go over and see the doctor anyhow. We aren’t going to hit them until about 0230, so go over there and see what he has to say.’

“I went to the aid station and there weren’t any other wounded in there. They had already been evacuated. The doctor said, ‘Take your pants off.’ I took my boots off, my pants off, and then when I pulled my socks off, he said, ‘Wow!’ He stopped me and said, ‘Put them back on. You are going nowhere. Lay down on that stretcher.’ I said, ‘I came walking in here from my company.’ He said, ‘Damnit, I am not requesting you to do it. I am telling you, it’s an order!’ I went over there, lay down, and fell asleep. Next thing I woke up in France in a warehouse-kind of building and then moved to a hospital in England because of frozen feet. It took another two months before I could return to the unit. I was still in my dress uniform from when we left Camp Sissonne.”

Lieutenant Stark of the 80th AAAB requested permission to test-fire a 57mm shell on an abandoned German Mark VI King Tiger tank: “With the taking of Cheneux and the bridge across the Amblève River, offensive action was temporarily halted. All antitank guns were placed in positions so that they covered all angles and approaches to the bridge across the river. I, desiring to replenish the supplies, principally rations and gasoline, tried to locate these supplies. The 1st Battalion had failed to draw supplies for its attachments, and in turn, the regiment had not made any provisions for the resupply of the attached antitank platoons, as it believed the battalions had included them in their requests. The battery commander and I finally received supplies from our own battalion headquarters. All echelons of the unit to which the platoon was attached were contacted, so that the situation would not recur.

“Near one of the gun positions overlooking the bridge was a knocked-out German Tiger tank. I was curious to know exactly what effect a shell fired from a 57mm gun would have on the front of the tank. Such an opportunity had not previously been afforded. Permission to fire the gun was received from the battalion commander. A special round of super high-velocity armor-piercing shell was fired from a distance of about 200 yards, and the front of the tank was penetrated slightly above the axle.”

Lt. Col. William B. Lovelady of the 33rd Armored Regiment supported the 119th Infantry Regiment between Stoumont and La Gleize, with a CP situated at Roanne, east of La Gleize. He recalled that “on December 22, 1944, about 9:30 PM, a young lieutenant from the 82nd Airborne was brought to my command post. He was wet, cold, and his face was all blackened. He had swum, waded, or whatever across the Amblève River to contact one of our outposts. He told them he had information for the Commanding Officer and asked to be taken there. You can imagine my surprise and gratitude to see him, since we had not been in contact with friendly forces for three days, and to learn that the paratroopers were just across the river cheered us. His message was that we were now attached to the XVIII Airborne Corps. He gave me a sketch of the disposition of forces just across the river, and asked me for a similar sketch or diagram of our forces. (Generally, just strung out across the road with the Amblève River on the right, and a steep wooded hill on our left.)

“Just before he left, he asked if we needed anything. We told him that the Germans were dug-in on the hill to our left and we needed artillery or mortars. He offered help. He said he would shoot a line across the river at dawn and we could call for and direct the fire from their Howitzers. This was done and we soon neutralized the enemy on the hill. This experience was one of the greatest in our five campaigns. We have no record of this incident in our book, Regimental or Combat Command B logs, and most, if not all, of the individuals that knew of this have either passed on, or are out of contact. Perhaps there is a mention of this incident in the Airborne or Regimental Journals.”

That same evening in La Gleize, bad news came through for Obersturm-bannführer Peiper: “The last hope for relief through units of the Division had to be given up. In the last radioed order which was received, Division ordered the encircled forces to fight their way out of the pocket. For unknown reasons the U.S. infantry and tank units [of the 30th Infantry Division] failed to resume their attack against La Gleize on 23 December, but the situation in the pocket nevertheless remained grave. Ammunition and fuel supplies were practically exhausted and no food supplies had arrived since the first day of the attack. Ammunition and fuel supplies by air on 22 December admittedly had arrived, but only about 10 percent of the supplies dropped by the three planes reached the target area, an amount which could have no effect whatever.”