The final course open to McClellan to counter Lee’s attack on his communications, and the one he chose to take, was to change his base to the James and, because he lacked a secure line for bringing forward supplies or heavy artillery to the Chickahominy, withdraw the Army of the Potomac to the James. The drawbacks of this option were that it would move the army from a position six miles from Richmond to one thirty miles from the Confederate capital. It also meant the abandonment and destruction of considerable amounts of supplies and disengaging in the face of an active enemy in order to make a difficult and risky march across White Oak Swamp.

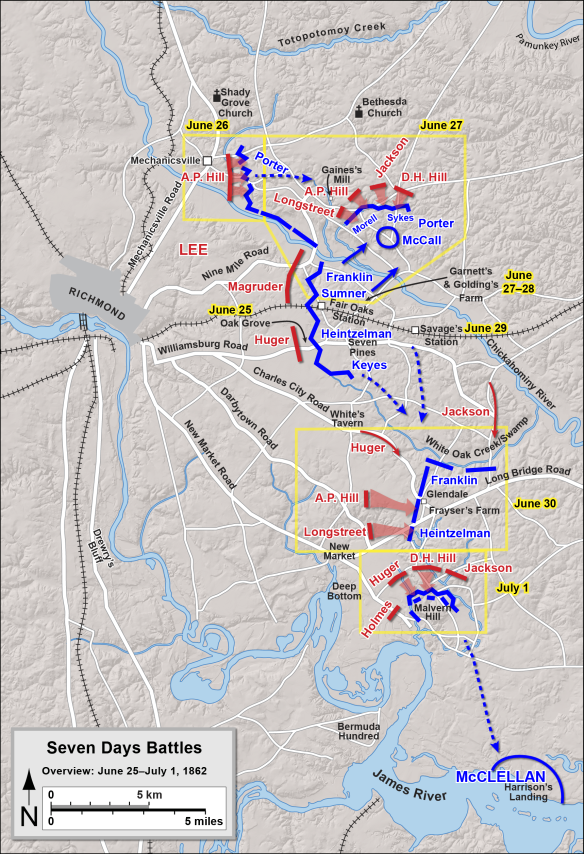

Nonetheless, on the night of June 27-28 McClellan issued orders for the retreat to the James. Keyes and Porter would immediately march south, cross White Oak Swamp, and establish a position from which they could cover the army’s supply trains and artillery reserve as they moved toward the James. To cover Keyes’s and Porter’s movements, Franklin, Heintzelman, and Sumner would remain between the Chickahominy and White Oak Swamp until the evening of June 29-30, when they were to cross the swamp and follow Keyes and Porter to the James.

For his part, Lee incorrectly anticipated that McClellan would fight for his supply line to the York River and intended to follow up his success at Gaines’ Mill by sending the bulk of his army to Dispatch Station to cut the Federals off from their supply base at White House. McClellan’s decision to withdraw to the James foiled this plan and it took Lee an entire day to figure out what McClellan was doing and revise his plans. Still hoping to destroy McClellan’s army, late on June 28 Lee set his sights on the Glendale crossroads through which the Federals would have to pass after crossing White Oak Swamp in order to reach the James. He ordered James Longstreet’s and A. P. Hill’s divisions to recross the Chickahominy, march south to the Darbytown Road, and push east toward Glendale, while to their left Benjamin Huger’s division advanced to Glendale on the Charles City Road. Meanwhile, Magruder’s division was to push east along the railroad and the Williamsburg Road, while Jackson, with his and D. H. Hill’s divisions, crossed to the south side of the Chickahominy at Grapevine Bridge. Together, Jackson and Magruder were to strike a strong blow against McClellan’s rearguard elements as they fell back toward the crossings of White Oak Swamp or, failing that, prevent them from reaching Glendale before Long- street, Hill, and Huger.

Thanks to Lee’s miscalculation of his intentions, by the night of June 28-29, McClellan had managed to get Keyes, Porter, and most of the army’s supply trains safely across White Oak Swamp, although in order to do so millions of dollars’ worth of supplies had to be destroyed and a field hospital of over two thousand men was abandoned to the enemy. Shortly before dawn on June 29, McClellan relocated his headquarters south of White Oak Swamp, leaving Sumner, Heintzelman, and Franklin to execute their orders without supervision to pull back toward White Oak Swamp and be able to cross it that night. As they were doing this, Magruder advanced his division eastward along the rail- road. After a sharp engagement with Magruder at Allen’s Farm, Sumner pulled his command back to Savage’s Station and together with elements of Franklin’s corps easily beat off a series of poorly conceived attacks by Magruder.

Despite an effort by Sumner to dissuade Franklin from carrying out McClellan’s orders to pull back from Savage’s Station, by midmorning on June 30 the entire Army of the Potomac was south of White Oak Swamp. At that time, in line with Lee’s hopes to execute a double envelopment of the Union army, Huger’s, Longstreet’s, and A. P. Hill’s divisions were approaching the Glendale crossroads from the west and Jackson’s and D. H. Hill’s were advancing on the White Oak Bridge crossing from the north. Aware of Lee’s intentions and the critical importance of the Glendale crossroads, McClellan spent the morning thoroughly surveying the area between the James and Glendale and personally directed the deployment of Heintzelman’s, Sumner’s, and Franklin’s corps. Three divisions under Franklin’s command were posted at White Oak Bridge to protect the army’s rear, while four divisions were positioned around Glendale to guard the intersection and the Willis Church (or Quaker) Road that connected it with Malvern Hill, where Porter’s and Keyes’s corps were establishing a defensive position covering Haxall’s Landing on the James.

At approximately 11 a. m., Jackson’s command reached White Oak Swamp but instead of vigorously attacking Franklin, Jackson decided merely to fire on his position with artillery. No doubt encouraged by the evident lack of any threat to his rear, McClellan decided to leave Glendale and rode south to Malvern Hill shortly after noon. After inspecting the defensive positions Porter and Keyes were preparing on Malvern Hill, McClellan pushed on to Haxall’s Landing to meet with John Rodgers and discuss how to best coordinate their operations. Rodgers told McClellan that because the rebels controlled City Point on the south side of the James, he did not believe the navy could support the Army of the Potomac at Haxall’s Landing, which was above City Point. McClellan then proposed Harrison’s Landing, a few miles downstream from Malvern Hill, for the army’s new base, which was the first good location below City Point. Although Rodgers would have preferred a point much lower on the James, McClellan persuaded him to accept Harrison’s Landing. Although the task of working out the final destination of the navy might have been delegated to a staff officer, there was nothing inappropriate about McClellan taking care of this himself.

What McClellan did next, however, almost defies belief. Even though his men were at the time engaged in a fierce battle near Glendale, the sounds of which were clearly audible at Haxall’s Landing, McClellan decided not to return to Glendale after resolving the question of the army’s final destination with Rodgers. Instead, he spent the afternoon on board the Galena, dining with Rodgers and traveling briefly upriver to watch the gunboat shelling of a Confederate division that had been spotted marching east along the River Road to- ward Malvern Hill.

McClellan’s failure to return to the scene of the fighting on the afternoon of June 30, without a doubt the critical moment in the retreat to the James, was unforgivable, and Stephen W. Sears is unquestionably correct to describe his actions as “dereliction of duty.” They were not, however, inexplicable. It is clear that McClellan’s behavior was attributable to a combination of demoralization rooted in a sense that events had turned against him for reasons beyond his control-indeed his preoccupation with the situation on the James may have been motivated by a desire to find some aspect of the situation he could control-and physical and mental exhaustion. His demoralization and exhaustion were evident in messages he wrote that evening. “I am well but worn out-no sleep for many days,” he advised his wife. “We have been fighting for many days & are still at it. I still hope to save the army.” To Stanton, he wrote: “We are hard pressed by superior numbers. . . . My Army has behaved superbly and have done all that men could do. If none of us escape we shall at least have done honor to the country. I shall do my best to save the Army.”

McClellan’s pessimism regarding the fate of his army reflected just how out of touch he was with the situation at Glendale. By the end of the day it was clear that the Battle of Glendale (or Frayser’s Farm) had ensured the Army of the Potomac would be able to reach the James safely. Good leadership at all levels of command, hard fighting by the rank and file, and problems on the Confederate side enabled the Federals to overcome McClellan’s absence from the field and equally inexcusable failure to appoint a single overall commander to oversee the battle. Although Lee was able to briefly penetrate the Union line west of Glendale, McClellan’s men were quickly able to contain the damage and preserve their line of retreat southward.