On 19 January 1644 the Scots army crossed the River Tweed into Northumberland. It comprised twenty-one regiments of foot and seven regiments of horse, some 18,000 men. Sir Thomas Glemham had only 2,000 men with which to oppose them and all he could do was retreat before the Scots, breaking bridges as he went. By the 25th the Scots had reached Alnwick and arrived at Morpeth two days later. On 1 February the Scots began their final march to Newcastle-upon-Tyne, although due to the weather they did not arrive before the town until the 3rd. The town was immediately summoned to surrender and the Scots’ surprise must have been great when they received a refusal from the Marquess of Newcastle himself – he had been promoted in the peerage for his victory at Adwalton Moor as had his lieutenant general, James King, as Lord Eythin.

On 15 January Newcastle had returned to York. For the next two weeks he gathered his forces to move north against the Scots and put plans for the defence of Yorkshire into place. On the 29th he set off north with 5,000 foot and 3,000 horse. Newcastle’s army arrived at Newcastle-upon-Tyne on 3 February, a few hours before the Scots army approached from the north, having taken only five days to complete the march.

With their summons refused the Scots were in a poor situation. They had intended to seize Newcastle-upon-Tyne and use it as a supply base. At this early part of the year the roads back to Scotland were in very poor condition and could not be used to supply such a large army. The obvious solution was to supply the army by sea but this needed a decent sized port. The coast of Northumberland was sadly deficient in such ports. The Marquess of Newcastle was aware of the precarious Scots position and his main objective became the defence of the line of the River Tyne. The Scots army sidestepped towards the west in an attempt to find an undefended crossing, as well as covering Newcastle-upon-Tyne. As the Scots army spread out, Newcastle was presented with an ideal opportunity to strike at them. On 19 February two Royalist columns crossed the Tyne and attacked the Scots’ quarters at Corbridge. In a hard-fought action the Scots were driven back with loss and their commander, Alexander Leslie, Earl of Leven, concentrated the whole army close to Newcastle to prevent a repetition.

Although Newcastle had successfully held the Tyne his army was exhausted and in need of rest. With this in mind, Newcastle withdrew his army to Durham. This presented Leven with an ideal opportunity, which the canny old soldier did not let pass. On 28 February the Scots crossed the Tyne and marched for Sunderland which was occupied on 4 March. The Scots now had their supply base and spent the next four weeks gathering supplies in preparation for their next move. On several occasions Newcastle tried to draw the Scots out of Sunderland to fight him in open ground. Leven realised that although his army outnumbered Newcastle’s, the veteran Royalist horse could be decisive. Leven refused to be drawn and several inconclusive actions were fought among the enclosures surrounding Sunderland. By the 25th Newcastle had realised that the Scots would not be drawn out on to ground of his choosing and pulled his troops back into Durham. On the 31st the Scots marched in pursuit of Newcastle and by 8 April had occupied Quarrington Hill, to the east of the town, effectively cutting Newcastle off from Hartlepool, his main supply port.

Things began to move rapidly. On the 12 April Newcastle received news that his Yorkshire army had been defeated at Selby and York was in danger of falling. During the early hours of the 13th Newcastle’s army set off for York, with the Scots in close pursuit. The Royalists arrived at York on the 19th, in the nick of time. The Scots and Lord Fairfax’s armies joined at Tadcaster on the 20th. In a matter of days the whole situation in Yorkshire had changed.

#

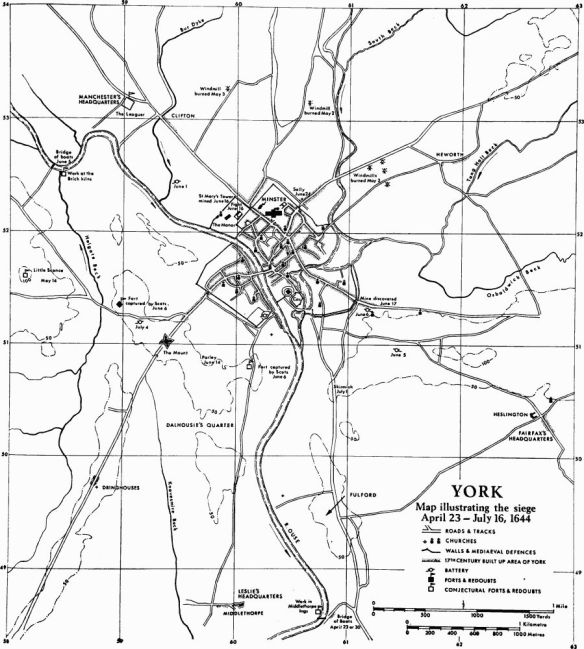

The Allies moved into their assigned zones, with the Scots covering the south and west sides of the town. Lord Fairfax was still short of infantry and several regiments of Scots foot, under Sir James Lumsden, were despatched to reinforce him on the eastern side of York. Although the Allied force heavily outnumbered the Royalist defenders, they were still too few to cover the whole circuit of the town’s defences. The area to the north of the town, between the Ouse and the Fosse, was covered only by cavalry patrols. Until this gap was sealed the Royalists would be able to bring supplies and reinforcements into the town, thus making the Allied task much more difficult.

It was obvious that the Allies needed more troops but where were they to come from? As it happened another force was within easy reach of York. In East Anglia the Earl of Manchester’s Army of the Eastern Association had captured Lincoln on 5 May, finally clearing the Royalists from his assigned area of responsibility. A deputation, including the Scots Earl of Crawford-Lindsey and Sir Thomas Fairfax, was despatched to talk to Manchester, who readily agreed to bring his troops to York. Manchester’s army began its march on the 24th and moved into position to the north of York on 3 June. The city was now fully surrounded and the siege began.

West of the Pennines, Prince Rupert was beginning his move to relieve York. To try to prevent this Sir John Meldrum had been sent to Manchester with two regiments of foot, including one Scots regiment. The bulk of the Allied horse had been sent to cover the passes through the Pennines – Cromwell is mentioned as visiting Penistone to cover the Woodhead Pass and Otley to defend the road from Skipton.

On 5 June Lord Fairfax put a plan into action to raise a battery against Walmgate Bar. To mask this move the Scots and Eastern Association troops formed up as though they were going to attack. While the defenders’ attention was drawn to the other side of the town, Fairfax made his move, capturing the suburbs outside the gate and raising a five-gun battery within 200 yards of the gate. Newcastle had made a mistake by not destroying the suburbs outside the town as these covered the enemy advances against the town’s weak points: its gates. It also gave the Allies defensible positions should the Royalists sally out of the town. Realising his mistake, Newcastle tried to rectify the situation on 8 June by burning down the buildings outside Bootham Bar. The attempt was unsuccessful and the fire raisers captured. In return, Manchester’s men tried to set fire to Bootham Bar’s wooden gates but this attempt was also unsuccessful.

Newcastle had received news of Prince Rupert’s advance into Lancashire. It is thought that this communication was carried out by signal fires from Pontefract Castle. At this stage of the war Prince Rupert had a reputation for invincibility and his northward march had put fear into the hearts of the Committee of Both Kingdoms. Several letters from the Committee to the commanders at York prompted them to divide their armies and send a substantial force over the Pennines. Leven, Fairfax and Manchester stuck to their task, telling the Committee that a division of their force would lead to disaster.

On 8 June Newcastle decided to open communications with the Allied commanders, more in an effort to waste time rather than a desire to come to an agreement. For one week the two sides exchanged messages and held discussions until, on the 15th, Newcastle peremptorily refused to accept the Allies’ surrender terms. It now became obvious that the previous week’s parleys had been a time wasting measure and Newcastle had no intention of surrendering the town. On the 16th the first attempt to storm the town took place.

Sir Henry Vane, a representative of the Committee of Both Kingdoms with the army at York, was sitting in his room writing a letter to the Committee, reporting the completion of two mines and the repair of a massive siege gun. Mines were a method of breeching defensive walls that had been used from ancient times. A tunnel was dug until it reached the walls and then a chamber was dug. Originally, a fire had been set in the chamber which burnt through the tunnel’s supports, causing the ground above to collapse, bringing the walls down with it. By the time of the Civil War the chamber was filled with gunpowder which was then exploded, blowing the wall above, and any defenders standing on it, into the air. Sir Henry was disturbed part way through writing his letter by a loud explosion. When he returned to his correspondence he added some important news:

Since my writing thus much Manchester played his mine with very good success, made a fair breach, and entered with his men and possessed the manor house [King’s Manor], but Leven and Fairfax not being acquainted therewith, that they might have diverted the enemy at other places, the enemy drew all their strength against our men, and beat them off again, but with no great loss, as I hear.

A mine had been exploded under St Mary’s Tower. Much of the tower and its adjacent walls had collapsed – the damage can still be seen today.

With the wall breached, Lawrence Crawford, Manchester’s Sergeant-Major-General of foot and a professional Scots soldier, ordered his assault force to attack. The attack by Manchester’s men seems to have caught the other commanders by surprise and the Royalists were able to concentrate on repulsing the attack. Newcastle took part in the defence, leading a party from his own regiment. The Parliamentarian force was repulsed with considerable loss – Manchester mentions, in a letter to the Committee of Both Kingdoms, losing 300 men in the assault, including 200 prisoners.

It is difficult to understand why Manchester carried out this attack without support from the other Allied commanders. Sir Thomas Fairfax gives one possible reason:

Till, in Lord Manchester’s quarters, approaches were made to St Mary’s Tower; and soon came to mine it; which Colonel Crawford, a Scotchman, who commanded that quarter, (being ambitious to have the honour, alone, of springing the mine) undertook, without acquainting the other Generals with it, for their advice and concurrence, which proved very prejudicial.

Another interesting point is the location of the attack. St Mary’s Tower forms one corner of the defences of the King’s Manor, which is outside York’s main defensive walls. Even if Manchester’s men had captured the Manor they would still not have breached the main defences, although their approach to Bootham Bar would have become much easier – any approach could be flanked by musket fire from the manor. What had happened to the second mine? Lord Fairfax had attempted to mine Walmgate Bar and Sir Henry Vane had reported its completion. Why had this mine not been exploded? Sir Henry Slingsby, one of the Royalist defenders, gives the reason: the mine had flooded. Simeon Ashe, the Earl of Manchester’s chaplain, gives this as the reason for Crawford blowing the mine when he did, rather than his ambition, as Sir Thomas Fairfax asserts.

The attack on the King’s Manor was the only attempt by the Allied commanders to assault the town. For two weeks after the failed assault things quietened. Both sides were holding their breath and waiting for Prince Rupert’s next move. On 30 June news reached the Allied commanders that the Prince had arrived at Knaresborough, within a day’s march of the town. They had no choice but to leave their siege lines and gather the army to oppose the Prince’s advance. Early on 1 July the Allies marched west from York and formed line of battle on Hessay Moor. This position blocked the Prince’s direct route from Knaresborough, via Wetherby.

It is now time to go back several weeks and briefly look at Prince Rupert’s advance into Lancashire and his approach march to York. On 16 May Rupert began his march to the north. His first move would be into Lancashire which, early in the war, had been a fertile recruiting ground for the Royalist cause. After the Battle of Sabden Brook, in May 1643, the county had come under Parliamentarian control, although many of its inhabitants still had Royalist leanings. Only one position still held out for the King, Lathom House, and one of Rupert’s objectives was to relieve it.

By 23 May Rupert’s growing force had reached Knutsford. He had been joined on the march by Sir John Byron’s Cheshire forces. The Royalists were confronted by the River Mersey which had only three crossing points between Manchester and the sea: Hale Ford, Warrington and Stockport. Hale Ford was covered by the defences of Liverpool and Warrington had been garrisoned. This left Stockport as Rupert’s choice of crossing point and he successfully brushed aside the locally raised garrison and continued into Lancashire on the 25th.

The immediate effect of Rupert’s entry into Lancashire was the raising of the siege of Lathom House. The besiegers withdrew into Bolton and this was Rupert’s next target. On 28 May Rupert’s army stormed the town in, if Parliamentarian news sheets are to be believed, one of the bloodiest episodes in the Civil War. That said, there is little evidence beyond Parliamentary propaganda to support the wholesale slaughter reported.

On the 30th the Royalists moved on to Bury, where they were joined by Newcastle’s cavalry, the Northern Horse, commanded once again by George Goring after his exchange, and several other small forces from Derbyshire. With the arrival of these reinforcements Rupert’s force had grown to 7,000 horse and 7,000 foot.

Rupert’s next target was Liverpool which would provide the Royalists with a good arrival port for Irish reinforcements. Leaving Bury on 4 June, the Royalists arrived before Liverpool on the 7th, having marched via Bolton and Wigan. Rupert summoned the town to surrender but its commander, Colonel Moore, refused. Between the 7th and 9th the town was bombarded and by the morning of the 10th a large enough breach had been made in the town’s defences to allow an assault. Although the attack was repulsed, Colonel Moore realised that his men could not hold out for much longer. During the night the defenders were evacuated onto the ships in the harbour and the Royalists occupied the town on the 11th.

While he was at Liverpool Rupert received a letter from his uncle, the King. This letter is one of the most controversial documents to have come out of the Civil War and historians are still disputing its correct interpretation. Rupert believed it was a direct order to fight the Allied forces besieging York and, after his defeat at Marston Moor, carried it with him for the rest of his life as proof of why he fought the battle.

On 20 June the Royalist army left Liverpool and began its approach march to York. By the 23rd they had reached Preston and then crossed the Pennines to Skipton by the 26th. After resting for several days the Royalists continued their march, arriving at Knaresborough on the 30th. On 1 July Rupert caught the waiting Allied commanders by surprise by not taking the direct line from Knaresborough to York but taking the longer route along the north bank of the River Ouse. By nightfall the Prince’s army was encamped in the Forest of Galtres, north-west of the city, and York had been relieved.