CSS Fredericksburg and CSS Virginia II, under fire from Union shore batteries and the USS Onondaga, in 1865. Tom Freeman

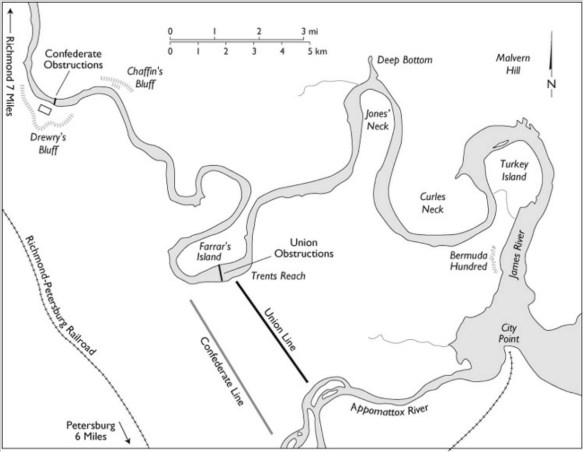

James River Operations, May–June 1864

The James River also became an active theater of operations again in 1864. After the withdrawal of the Army of the Potomac from the Virginia peninsula in August 1862, the James was a relatively quiet sector as the main action moved to northern Virginia and Maryland. For a time in the spring of 1863, however, actions along the Nansemond River, which flowed into the James from the south about fifteen miles west of Norfolk, had seemed to portend major fighting in this theater. Reports that Union troops planned an advance on Petersburg from their base at Suffolk on the Nansemond alarmed General Robert E. Lee. He sent General James Longstreet with two divisions to the south side of the James to counter this anticipated thrust.

When no movement by Union forces materialized, Longstreet converted his operations into a foraging expedition to obtain provisions for the Army of Northern Virginia from this region as yet lightly touched by the war. With 20,000 men, Longstreet also contemplated an attack on Suffolk. Detecting Confederate movements to the Nansemond, Federal commanders feared an effort to recapture Norfolk itself. “If Suffolk falls,” Acting Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee warned Welles on April 14, “Norfolk follows.”

To help the army defend Suffolk, Phillips Lee sent a half dozen shallow-draft gunboats—converted ferryboats and tugs—into the narrow, crooked river. These fragile craft became the Union’s first line of defense, doing more fighting and suffering more damage in artillery duels with Longstreet’s guns than did the Union soldiers. In one brilliant operation led by navy Lieutenant Roswell H. Lamson on April 19, a gunboat landed troops plus boat howitzers manned by sailors and captured five field guns and 130 prisoners. The loss of this battery was “a serious disaster,” Longstreet reported. “The enemy succeeded in making a complete surprise.” Two weeks later, after the battle of Chancellorsville, his divisions were recalled to the Army of Northern Virginia on the Rappahannock. The James River lapsed into quiescence again.

But with the opening of Grant’s Overland Campaign in May 1864, the James became a key focal point of Union operations. For political reasons, President Lincoln had felt it necessary to give General Benjamin Butler another command after his removal from New Orleans. In November 1863 Butler became head of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina, the army counterpart of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Butler formed the Army of the James in April 1864. Grant gave him the assignment of moving up that river against Richmond, while the Army of the Potomac began its campaign against General Robert E. Lee across the Rapidan River. Phillips Lee’s gunboats on the James would have a crucial role in this effort.

On May 5, 1864, Butler’s 30,000-strong army boarded transports and steamed up the James River to a landing at City Point nine miles from Petersburg. Convoyed by five ironclads and seventeen other gunboats, several of which dragged for torpedoes, the meticulously planned movement went off without a hitch. The next day, however, a 2,000-pound torpedo blew the USS Commodore Jones into splinters with the loss of forty men killed. And on the following day, the USS Shawsheen, dragging for torpedoes near Chaffin’s Bluff far up the river, was disabled by a shot through her boiler and captured along with most of her crew.

Confederates had planted hundreds of torpedoes in the river and had prepared torpedo boats to attack Lee’s ships. Lee decided to create what amounted to a minesweeping fleet of three gunboats, which he named the “Torpedo and Picket Division.” He put Lieutenant Lamson in charge of this division. Lamson had been assigned to command of the USS Gettysburg, a captured blockade-runner converted into the fastest blockading ship in the squadron. Lee asked Lamson to give up this plum assignment, at least temporarily, to take up minesweeping duty.

Lamson threw himself into this dangerous task and in his first day fished up and disarmed ten torpedoes, one of them containing almost a ton of gunpowder. Within three weeks his minesweeping fleet had expanded to eight gunboats, ten armed launches, and 400 men. Lamson explained how he turned the Confederates’ weapons against them. “I have had some of the large torpedoes we seized on our way up refitted and put down in the channel above the fleet” as protection from Confederate ironclads at Richmond if they came down. “I have [also] made some torpedoes out of the best materials at hand here, and have each one of my vessels armed with one containing 120 pounds of powder. . . . The Admiral expressed himself very much pleased with them and is having some made for the other vessels.”

Butler had advanced up the James as far as Drewry’s Bluff only eight miles from Richmond. But the Confederates under General Beauregard attacked and drove him back to the neck of land between the James and Appomattox Rivers. Meanwhile, Grant had been fighting and flanking Robert E. Lee’s army down to Cold Harbor east of Richmond. Rumors and reports abounded that the Confederate James River Fleet of three Virginia-class ironclads and seven gunboats would sortie down the river to attack the Union fleet. Phillips Lee reported “reliable” intelligence that the “enemy meditate an immediate attack upon this fleet with fire rafts, torpedo vessels, gunboats, and ironclads, all of which carry torpedoes, and that they are confident of being able to destroy the vessels here.” The Confederates did indeed “meditate” such an attack, but they were delayed by difficulties in getting the ironclads through their own obstructions at Drewry’s Bluff. They found the Union fleet on alert and called off the sortie, instead exchanging long-range fire with Union ironclads across a narrow neck where the James made a large loop creating a peninsula known as Farrar’s Island.

The possibility of such a sortie caused Union officials to consider sinking hulks at Trent’s Reach to create obstructions to prevent it. Phillips Lee was opposed; he wanted to fight enemy ironclads, not block them. “The Navy is not accustomed to putting down obstructions before it,” he declared. “The act might be construed as implying an admission of superiority of resources on the part of the enemy”—in other words, Lee might be accused of cowardice. Instead, he and his officers “desire the opportunity of encountering the enemy, and feel reluctant to discourage his approach.” Lee also hoped that a successful fight with enemy ironclads would get him promoted to rear admiral.

General Butler urged the sinking of obstructions; Phillips Lee told him bluntly that if they were to be placed, “it must be your operation, not mine.” Butler responded that he was “aware of the delicacy naval gentlemen feel in depending on anything but their own ships in a contest with the enemy,” but “in a contest against such unchristian modes of warfare as fire rafts and torpedo boats I think all questions of delicacy should be waived.” Exasperated, Lee countered that he would only sink the hulks “if a controlling military authority [that is, Grant] requires that it be done.”

Grant did so order it when he decided to cross the army over the James and attack Petersburg. Phillips Lee reluctantly ordered Lieutenant Lamson to do it, which he did on June 15. And sure enough, the Northern press accused Lee of being afraid to fight the rebels. Lee was especially outraged by an article in the New York Herald, his chief tormentor, which declared that the placing of obstructions “has called an honorable blush to the cheek of every officer in his fleet. . . . [Lee] has ironclad vessels enough to blow every ram in the Confederacy to atoms; but he is afraid of the trial.” The Herald subsequently backed down and admitted that Grant had ordered the obstructions, but in a parting shot the newspaper stated that he did so because “he has no confidence” in Lee.

By late June 1864, Grant had troops in place in front of both Petersburg and Richmond and settled in for a partial siege. Affairs on the James River also settled into a stalemate in which the two fleets remained behind their respective obstructions. The Union warships continued to convoy the steady stream of supply steamers up the river to Grant’s base at City Point. Welles ordered Lee to turn over the James River Fleet to Captain Melancton Smith and to move his own headquarters to Beaufort, North Carolina, where he could give more attention to the blockade.

With the concentration of so many vessels on the James River in May and June, the blockade off North Carolina had suffered some relapse. More and more runners were getting through. One of the most egregious violations of the blockade was accomplished by the CSS Tallahassee. Built in England as a fast cross-channel steamer named Atalanta, it became a blockade-runner in 1864 and made several successful runs to and from Wilmington. Because of its speed and strong construction, the Confederate navy purchased it in July 1864 and converted it into a commerce raider armed with rifled guns. Renamed the Tallahassee, she slipped out of New Inlet on the night of August 6, avoided two blockaders that fired on her in the dark, and cruised north along the Atlantic coast on the most destructive single raid by any Confederate ship. In the next nineteen days, she captured thirty-three fishing boats and merchant ships, burning twenty-six, bonding five, and releasing two. Naval ships hunted her from New York to Halifax and back to the Cape Fear River, which she reentered August 25 just ahead of pursuing blockaders.

The Tallahassee’s exploits intensified Northern criticism of Phillips Lee and the Navy Department. Lee issued a flurry of new orders to tighten the cordon of ships off the two inlets of the Cape Fear River. By September these measures were paying off. Major General William H. C. Whiting, Confederate commander of the District of North Carolina and Southern Virginia, lamented “the loss of seven of the very finest and fastest of the trading fleet” in September. “The difficulty of running the blockade has been lately very great. The receipt of our supplies is very precarious.” One reason for the navy’s success in catching these runners was that the Tallahassee had taken all the anthracite coal available in Wilmington for her cruise. Left with only bituminous coal, the runners spewed clouds of black smoke that revealed them to the blockade fleet.

Postscript 1865

The capture of Fort Fisher closed the last blockade-running port except faraway Galveston. (A few runners had been getting into Charleston in recent months by using Maffitt’s Channel close to Sullivan’s Island. The last one got in just before the evacuation of Charleston on the night of February 17–18, 1865.) Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens considered the loss of Fort Fisher “one of the greatest disasters which has befallen our Cause from the beginning of the war.” The advance up the river by Porter’s gunboats and army troops to capture Wilmington on February 22 was something of an anticlimax. The same was true of the occupation of Charleston when the Confederates evacuated it on February 18 after Sherman’s army cut the city’s communications with the interior on their march through South Carolina. Clearly, the end of the Confederacy was in sight. But action continued on several fronts during the winter and spring of 1864–65.

While part of the James River Fleet was absent on the Fort Fisher campaign, Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory ordered Flag Officer John K. Mitchell, commander of the South’s own James River Fleet, to attack Grant’s supply base at City Point. Heavy rains in the James River’s watershed raised the river level enough that Confederate ironclads had a chance to get over the Union obstructions at Trent’s Reach twenty river miles above City Point. “I regard an attack upon the enemy . . . at City Point to cut off Grant’s supplies, as a movement of the first importance,” Mallory told Mitchell. “You have an opportunity . . . rarely presented to a naval officer and one which may lead to the most glorious results to your country.”

With three ironclads carrying four guns each—the Virginia II, the Fredericksburg, and the Richmond—and eight smaller consorts, including two torpedo boats, Mitchell came down on the night of January 23–24. The Union fleet of ten gunboats, including the double-turreted monitor USS Onondaga with its two 15-inch Dahlgrens and two 150-pound rifles, dropped several miles downriver to a spot where they had maneuvering room against the enemy—or so their commander, Captain William A. Parker, later explained. But to General Grant, it looked like a panicked retreat. Grant himself untypically pushed the panic button. He fired off telegrams to Welles and ordered naval vessels back up to the obstructions on his own authority, complaining that “Captain Parker . . . seems helpless.” Two of the three Confederate ironclads ran aground at the obstructions; army artillery blasted them and the Fredericksburg, which had gotten through but was forced to return; the Onondaga came back upriver and added its big guns to the heavy fire that sank two Confederate gunboats and compelled the rest to retreat.

In the end, this affair seemed like much ado about very little. But it resulted in the replacement of both fleet commanders. Lieutenant Commander Homer C. Black replaced Parker despite the latter’s pleas for a second chance. He was later tried by court-martial and found guilty of “keeping out of danger to which he should have exposed himself.” But the court recommended clemency in view of his thirty-three years of honorable service, “believing that he acted in this case from an error of judgment.” Welles accepted the clemency recommendation, but Parker’s career was essentially over. On the Confederate side, Mallory replaced Mitchell with Raphael Semmes, recently promoted to admiral and without a command.30 Semmes’s principal accomplishment as chief of the James River Squadron was to order its ships blown up when the Confederates evacuated Richmond on the night of April 2–3, 1865.