When Pepys wasn’t being seasick (which he was, rather a lot), he spent his nights watching the sailors dance on deck, and his days producing a paper for Dartmouth to justify the king’s decision. “Arguments for Destroying of Tangier” was a model of clarity, and it reflected governmental thinking pretty accurately. England’s high hopes for Tangier as a naval base and a major trading center had not materialized; without the help of Parliament, which was conspicuously unforthcoming, the king could no longer afford to support it. Sooner or later it would fall either “to some Christian enemy” or to the Moors, who would use the mole and the fortifications which had cost so much in blood and money, and would establish “such a den of thieves and pirates, as would prove of worse consequence to the whole trade of the Levant . . . than all that can arise from the whole united force of corsairs infesting that sea at this day.” It was better for the English to destroy Tangier than to let it fall into the hands of others.

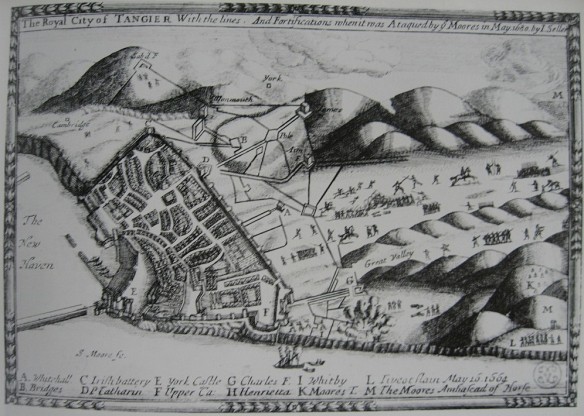

The fleet arrived on September 14, 1683, one month after leaving England, to find a Moorish army camped outside the walls. This was going to make a clandestine demolition rather difficult, and Dartmouth hadn’t bargained on it. It was no secret that Mawlay Isma’il had designs on Tangier; or that the Ottoman emperor, Mehmed IV, was urging him to make holy war on all the Christian enclaves along the coast of Morocco—not only Tangier, but the Spanish and Portuguese outposts of Ceuta, Larache, Melilla, and Mazagan. But the four-year truce that had been brokered in 1680 still had just over a year to run, and Dartmouth’s latest intelligence had been that Umar ben Haddu’s successor as qaid, Ali ben Abd Allah al-Hammami, was eager to see it extended. What had gone wrong?

Lieutenant-General Sir Percy Kirke (The Elder), painting by an unknown Artist, c. 1680.

Before even stepping ashore, he invited the governor, Colonel Percy Kirke, aboard the Grafton and showed him the king’s commission. Kirke was perfectly happy to hand Tangier over to Dartmouth. “He do most seemingly collectedly bear it and very cheerfully,” Dartmouth told Pepys afterward. When the new governor read Kirke’s intelligence report on recent events, he saw why. Relations between the garrison and al-Hammami had begun to deteriorate in May, when the qaid complained that some stained glass which Kirke had promised to get for him from England hadn’t arrived. An escalating tit-for-tat exchange of sanctions followed. The Moors refused to sell the garrison straw for their horses until the glass arrived. The English refused (quite understandably) to hand over a supply of gunpowder, even though this had been agreed as a condition of the truce. The Moors barred the English from walking outside the town walls. The English barred the Moors from entering the town. Now the qaid had gathered an army, with a view to intimidating the garrison; but there was still a chance to avoid war, reckoned Kirke, adding disarmingly that this was “a work that seems to be reserved for your lordship’s prudence and dexterity.” Over to you, in other words.

Dartmouth thought briefly of simply telling al-Hammami his plans, but Pepys and Sheres managed to dissuade him. There was nothing for it but to press ahead in an increasingly uneasy and unreal climate of semi-secrecy. Pepys and Trumbull convened a court to hear claims of title to property, pretending that they were carrying out a general survey and valuation, although everyone in the town now suspected the real reason. Sheres went round declaring that the demolition work would take at least three months, which infuriated Dartmouth, who insisted it could all be done in a fortnight. Colonel Kirke turned into a fawning yes-man, agreeing with every passing whim of Dartmouth’s and prefacing every utterance with the words “God damn me!” His wife dropped heavy hints that she knew all about the imminent evacuation of the colony, while Dartmouth withheld everyone’s letters arriving from England in case they held a clue as to his plans. Anxious to put on a show of force in front of the Moors, he brought a thousand seamen ashore and had them parade in full view of the enemy camp along with his soldiers, as though they were reinforcements for the garrison; but this only made matters worse, since al-Hammami now demanded to know why the English had sent such a powerful army to Tangier. Trumbull grew so depressed at the thought of all the fees he could have been earning back in London that he asked to go home. Dr. Ken kept everyone’s spirits up by delivering sermons in which he denounced the vicious ways of the townspeople and the garrison.

If Pepys is to be believed, those ways were indeed rather vicious. “Nothing but vice in the whole place of all sorts,” he wrote in his private notes, “for swearing, cursing, drinking and whoring.” The hospital was full of syphilitics. Kirke had got his wife’s sister pregnant and packed her off to Spain to have the baby. On one occasion he had sex with a woman in the middle of the marketplace, and he kept a whore in a little bathing-house he had furnished for the purpose; while he was visiting her, his wife entertained the colonel’s young officers in her bedchamber. Admiral Arthur Herbert, the admired commander of the Mediterranean squadron who had managed to secure peace with Algiers, kept a house and a whore in Tangier. His officers proudly recounted stories of his exploits, such as the time when he got his surgeon dead drunk, had him stripped naked, “and one of his legs tied up in his cabin by the toe, and brought in women to see him in that posture.”

The garrison’s soldiers were often drunk, both on and off duty, and they beat the townspeople and stole from them with impunity. Kirke himself was said to owe the local traders £1,500, but when they asked him to settle his debts all they got was “God damn me, why did you trust me?”

On the afternoon of Thursday, the 4th of October, three weeks after arriving in Tangier, Lord Dartmouth went to the town hall and announced “the great secret.” He had spent days working on his speech, discussing it with Pepys and Trumbull and making endless revisions. He took care to explain that everyone would be compensated for the loss of their property, all debts would be paid, transport home would be arranged at the king’s expense. If he expected a hostile reception, he couldn’t have been more wrong. Bells were rung in the steeples, bonfires were lit all over town in celebration. The mayor and aldermen wrote a letter of thanks to Charles II for his compassion in “rescuing us from our present fears and future calamities, in recalling us from scarcity to plenty, from danger to security, from imprisonment to liberty, and from banishment to our own native country.” The officers of the garrison handed in an address for the king, expressing “all the joy that our hearts are capable of ” and telling him how much “we applaud and admire the wisdom of your Majesty’s counsels on this important affair.” No one was going to miss Tangier.

Dismantling an entire community was a complicated business. Pepys compiled a list of 180 freeholders and leaseholders who needed to be compensated—civilians, army officers, and absentee landlords. (Some were more absent than others: the list included the king of Portugal, legal owner of the Dominican church, and Sir Palmes Fairborne, who had been dead for three years.) There was some wrangling over values, but things were settled within weeks, at a cost to the crown of about £11,300. Debts had to be proved and paid. Goods had to be inventoried—one careful soul catalogued the contents of the public library, which included Fuller’s Worthies of England, the plays of Sir William Davenant, and Pascal’s Mystery of Jesuitism, but not Milton’s Paradise Lost, which was marked “lost.”

And the population, which had more than doubled since the 1660s, had to be shipped out. There were currently 4,000 of the king’s men—soldiers, sailors, and engineers—in Tangier. Many had their wives and children with them (Lord Dartmouth reckoned there were 400 Christian children in the town). The civilian population had taken a dip after the siege of 1680, when a number of merchants and tradesmen moved to the safer shores of Spain, but it stood now at well over a thousand, and everyone must be moved to Christendom and safety.

The first vessel to go was a hospital ship called the Unity, which set sail toward the end of October, carrying sick and crippled veterans and a sprinkling of women and children. A few days later the mayor boarded the St. David and “he and the best families of the citizens sailed away at break of day for England.”20 The lawyer Trumbull, whose grief at his loss of earnings was boring the garrison to death, was given permission to go home at the same time.

Even as the Unity was leaving the Bay of Tangier, Lord Dartmouth’s engineers were excavating a series of experimental mines. On October 19, his master gunner, Captain Richard Leake, set off two explosive devices under the arches at the landward end of the mole, but the earth was so loosely packed that they did no damage. The next day, Sheres, who seems to have taken charge of the demolition of the mole, drilled out a cavity, packed it with powder, and detonated it to more effect. But there was a vast amount of earth and rubble to move. He computed it at 2,843,280 cubic feet, or 167,251 tons, and estimated that it would take a thousand men nearly eight months to clear the site.

The other teams were more efficient. By November 5, Dartmouth could report to London that the mines laid in the town and the citadel were all finished and ready to blow. In the meantime Sheres managed to break up the caissons at the seaward end of the mole, but he was still having huge problems with Sir Hugh Cholmley’s earthworks. Dartmouth deployed 2,000 men at a time to remove the rubble by hand and tip it into the bay: “This good will follow,” he said, “that the harbor will be fully choked up by it.” The sight of 2,000 laborers swarming over the mole from dawn till dusk and hurling it stone by stone into the bay did give the watching Moors a bit of a clue that something was afoot; but by now Dartmouth had acquainted al-Hammami with his intentions. There was no point in secrecy.

On January 21, 1684, Dartmouth’s officers reported that the mole was “so entirely ruined and destroyed, and the harbor so filled with stones and rubbish” that it was “in no capacity to give any kind of refuge or protection to the ships or vessels of any pirates, robbers, or any enemies of the Christian faith.” The withdrawal of the English garrison had begun the previous week, when mines were sprung at Pole Fort and the other outlying defenses, and the ground between them and the town walls were strewn with iron spikes to deter an opportunistic cavalry charge by the Moors. On February 3, Dartmouth gave the order to blow up one of the mines at York Castle, the old Moorish fortress on the shore, and another in the Upper Castle. The senior officers of the garrison gathered to hear Dr. Ken read a prayer of thanks to God at the town hall, the church having been stripped of its furnishings, its seats, even its marble pavement, which Lord Dartmouth sent home to decorate the king’s chapel at Portsmouth. For the next two days soldiers pulled down as much of the remaining buildings as they could, throwing the debris into the common sewer. At nine in the morning of February 6, the troops who were left ashore began to embark in small boats for the fleet at anchor in the bay, as one mine after another was blown. Rubble flew high into the air. Fires were started. Peterborough Tower in the Upper Castle collapsed with a roar, “on which many of the Moors appeared, giving a great shout.”

Lord Dartmouth was the last to leave, springing the final mine himself before being rowed out in his barge to the Grafton, as thousands of Moors rode down from the hills toward the ruined town. He delayed sailing for home for several days, to negotiate the release of Lieutenant Wilson, the commander of Henrietta Fort who had been captured by Umar’s soldiers four years earlier. “I thought it not for your Majesty’s honor to leave a commissioned officer behind that had behaved himself so very well in your service,” he told Charles II. “And I believe [he] will do again upon a little encouragement, though at present his misfortunes and long captivity seem too much to have dejected him.”