Napoleon and the Consular Guard at Marengo, 14 June 1800, by Alphonse Lalauze.

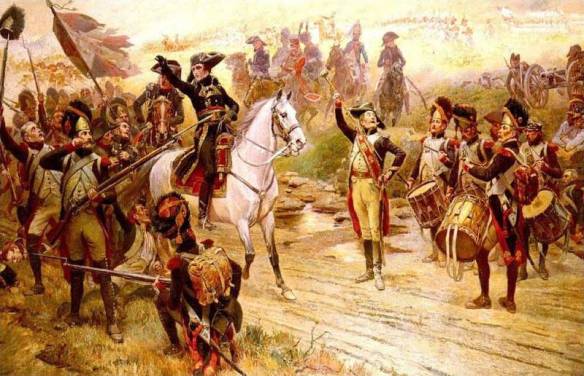

Napoleon Conferring with Desaix in Marengo, 14 June 1800 by Keith Rocco.

On the afternoon of 13 June 1800 the French advance guard, Gardanne’s augmented division (5,300 infantry, 685 cavalry, and 2 guns) drove the Austrian covering force, 4,000 strong, back towards Alessandria. By 6 pm the Austrians were back to the village of Marengo, only 4 kilometres from the place where the Bormida river protects the eastern approach to Alessandria. Gardanne decided to attack the village in strength and his opponent General O’Reilly, one of the many officers of Irish descent in the Hapsburg service, decided not to stand against him as he had in his rear the Fontanove stream, a drainage ditch with steep banks and a marshy bottom. The French therefore followed their opponents until they came under fire from the fourteen guns which Melas had established in a tête de pont on the east bank of the Bormida.

Gardanne, a mediocre general, then considered his work done and settled down with his outposts between the river, on the left, and the Alessandria–Marengo road on his right. He reported, falsely, that he had driven O’Reilly across the Bormida. He also gave Bonaparte to understand that he had destroyed the bridge across that river. Marmont, now a general, realized that both bridge and tête-de-pont were still intact and brought forward eight guns in an attempt to overcome the fire of the Austrian battery. He was unsuccessful and went back to Gardanne, whom he found sitting in a ditch, to propose that the infantry should storm the fortification. When Gardanne refused, Marmont started to ride back 11 kilometres to Bonaparte’s headquarters. Being overtaken by a heavy storm and the road being abominable, he decided to spend the night in a wayside farmhouse and was not able to report to the First Consul until the morning.

Bonaparte was still convinced that Melas would either make for Genoa or try to break north, crossing the Po at Valenza. To guard against the first move he had, at noon, ordered Desaix with Boudet’s division (5,316 men) to march south-west through Rivalta so as to cut the Alessandria–Genoa road at Serravilla. During the evening a story from an Austrian deserter was brought in to the effect that Melas had made a detachment to Acqui, 32 kilometres to his right rear. This story was true and reinforced Bonaparte’s conviction that Melas was intending to move to a flank. In fact the Austrian detachment consisted of only a single squadron of dragoons, 115 men, but Bonaparte ordered Lapoype to take his division (3,462 strong) towards Valenza. Further confirmation of Bonaparte’s delusion came with Gardanne’s report that O’Reilly was on the west bank of the Bormida behind a broken bridge. The destruction of the bridge was also, according to Bonaparte, reported by his ADC, Lauriston, though that officer always denied that he made such a report.

Convinced that he had nothing to fear from a frontal attack, Bonaparte went to bed 10 kilometres behind Marengo with his army widely dispersed. Gardanne’s 5,900 men were at and in front of Marengo with Chambarlhac’s division (3,400) in close support. These two divisions with two cavalry regiments and 6 or 8 guns were supervised by General Victor and there was no reinforcement nearer than General Lannes with Wattrin’s division (5,000) and 12 guns (5 of them Austrian pieces captured at Montebello), bivouacked 7 kilometres behind Marengo near San Giuliano Vecchio. In succession behind them were the main body of the cavalry (2,500), Monnier’s division (3,600 with 2 guns) and, close to headquarters, the Consular Guard (1,000 infantry, 250 cavalry, and 8 guns).

Meanwhile Melas in Alessandria had allowed himself to be haunted by the fear that he would be crushed between the Armée d’Italie and the Armée de Réserve. He believed that the former force had pushed 12,000 men forward towards Savona and Voltri and that it would soon be reinforced by Massena with the former garrison of Genoa so as to make the total corps in his rear, according to his calculations, 22,000. In fact there were scarcely 11,000 men in all facing him on the west and the garrison of Genoa was in no state to undertake any exertions. Believing however that he was threatened by 22,000 men to the west and 35,000 to the east, Melas decided that:

So situated and with the destiny of Italy at stake, our only course was to attack the enemy with the aim of cutting our way through to the Hereditary Lands [Milan and Mantua] on the south bank of the Po, thus bringing help to the threatened fortresses of Mantua, Legnano and Verona while covering the west Tyrol [Trentino].

He gave orders to launch an attack to the east at dawn on 14 June. He divided his field force, 23,000 infantry, 7,600 cavalry and 100 guns, into three unequal columns.

The main column of 20,238 men, including 37 squadrons of cavalry, was to attack straight down the road through Marengo and San Giuliano making for Tortona and Piacenza. Its right would be covered by O’Reilly with only 3,000 men. On the left Lieutenant-General Ott with 7,500 men, including only 4 squadrons, was to move on Sale but Melas anticipated that it would find the French holding Castel Ceriola. If Ott could not force his way through at this point he was to fall back towards the Bormida, drawing the French after him. He would then detach some of the powerful cavalry force from the centre column to the left and cut the French off.

To make the debouchment from the fortress as quick as possible, the Austrian engineers had put up a pontoon bridge within the tête de pont but, although there were now two bridges across the Bormida, there was only one gate to that earthwork and none of the columns could emerge until O’Reilly, whose detachment had spent the night on the east bank, had driven in Gardanne’s outposts. This done, the leading division of the centre column, 6 battalions and 9 squadrons under Lieutenant-General Haddick, marched out and, covered by the fire of 16 guns, formed three-deep line with each flank resting on the Bormida.

This covering bombardment was clearly heard at French headquarters at Toro de Garofoli, 12½ kilometres to the east, where Bonaparte had just confirmed the order for Lapoype’s division to march on Valenza. Even when, at about 9.30 am, a message from Victor told him that the enemy were massing for a major attack he refused to believe it, asserting that it could only be a diversion to conceal the flank march that he expected. It took Marmont’s report to convince him of the truth:

The First Consul, astonished by the news, said that an Austrian attack seemed impossible and added ‘General Gardanne told me that he had reached the river and destroyed the bridge’. I replied, ‘General Gardanne made a false report. Last night I was closer to the tête de pont than he ever went. It is neither taken nor blockaded by our posts and the enemy has been able to debouch from it in his own time.’

Realizing the danger at last, orders were sent for all the available troops – the divisions of Wattrin and Monnier, the cavalry, and the Consular Guard – to march westward while ADC’s were sent to recall Desaix and Lapoype. Until they arrived there would be only 22,000 French against 31,000 Austrians.

THE AUSTRIANS ATTACK

Fortunately for the French the enemy were making slow progress. Melas’ detailed orders called for extreme deliberation. He had ordered the centre column to form in four lines, the first consisting of Haddick’s division and the second of Kaim’s (7 battalions) also in line. Behind them would come the 1,800 horsemen of Elsnitz’ cavalry division and in rear, marching in column, Morzin’s 11 battalions of grenadiers. With only one narrow gateway from which they could emerge, the deployment of this column was certain to be slow and it was made much slower when, at 9 am a message arrived from the squadron of dragoons detached to Acqui reporting that they were being attacked by ‘a heavy column of cavalry followed by infantry’. Since there were no substantial French forces near Acqui on that morning, it can only be supposed that the squadron leader had met a patrol probing forward from the Armée d’Italie and had magnified it in his imagination into a force of all arms.

False though this information was, it confirmed Melas’ worst fears of being crushed between two French armies and he reacted by ordering Nimptsch’s cavalry brigade, half his cavalry division, to march immediately on Acqui. The confusion caused by turning six strong squadrons in the confined space inside the tête de pont, already packed with infantry and guns waiting to get forward, greatly delayed the deployment while Ott’s left-hand column had to wait on the west bank of the Bormida until the cavalry had filed back across the bridges.

Impatient of the delay, Haddick sent his division against Marengo without waiting for the whole column to be formed. His six battalions made a brave show in their white coats, advancing in line with their bands playing and their colours flying. They were halted at the Fontanove ditch, deep, marshy, and edged with a dense thicket while Gardanne’s division on the other side poured volleys into the Austrians as they struggled to cross. A few men gained the far side only to be shot down and Haddick, recognizing that his task was impossible, ordered a retreat. Hardly had he done so than he was mortally wounded before he could consult Kaim who, as soon as Haddick’s men had passed through his own division, threw his own seven battalions at the obstacle only to be repulsed in the same way. It was now recognized that the Fontanove could not be crossed without footbridges and the only pioneers available were with the grenadier division in the rear.

While the bridges were being brought forward, Melas ordered some cavalry to search for a crossing place on the right and to charge in on the flank of the defenders. Three squadrons of the Emperor’s Dragoons did succeed in getting across at a point where the horses could pass in single file but, while they were still forming to charge, they were charged in their turn by French cavalry and driven over the steep banks into the stream, an experience few of them survived.

On the right O’Reilly’s men were held up by the farmhouse of Stortigliano, in the narrow gap between the Bormida and the Fontanove. Held by 400 men of the 44me and 101re demi-brigades the garrison was weakened when the hundred men of the 101re decided that their proper place was with their own unit. The remainder, although they were surrounded and suffered 194 casualties, held out until evening, although they could not entirely block the Austrian advance against the French left.