Award ceremony for the panzermänner from the 503 (schwere) SS-PzAbt near Arnswalde (Pomerania) in February 1945. From right to left are SS-Ustuf. Karl Bromann (future Ritterkreuzträger and panzer ace), SS-Stubaf. Friedrich “Fritz” Herzig (future Ritterkreuzträger and Kdr. of 503 s.SS-PzAbt).

From February to March 1945 the division had rough battles in Danzig, Stettin and Stargard. In March they fought on the Oder front and in Neukölln, where they suffered great losses. On March 20, 1945 the exhausted division was put into reserve, but already on April 16 the Nordland was sent to protect Berlin.

On Stettin’s quayside, Ziegler and his men disembarked, climbed into their vehicles and left the bombed-out city behind them. The Nordland’s grenadiers drove south into the quiet Pomeranian countryside where they married up with their panzer battalion, now reformed and boasting 30 Panthers and 30 assault guns. This would be the last period of calm the division would experience before its extinction in the rubble of Berlin three months later. From this moment until the end, the Scandinavian Waffen-SS would be involved in bitter fighting across the east German landscape, being worn down by battles at Arnswalde, Massow, Vossberg and Altdamm. At each location, now all in modern-day Poland, they would leave yet more comrades behind, lying dead in the mud. For now though, the war seemed a long way off as the men spent more than a week training during the day and then relaxing night in the local Pomeranian hostelries, eating, drinking and dancing with the local farm girls.

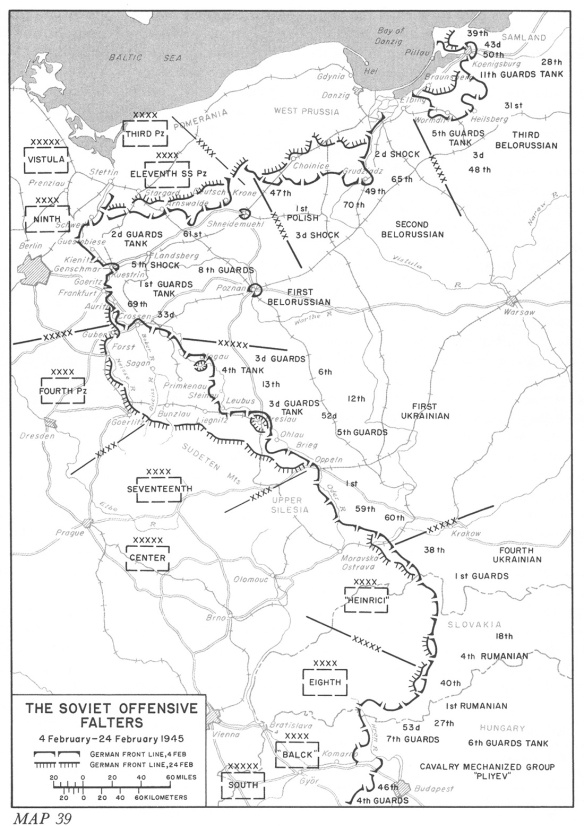

To the east and south the Red Army was equally happy, but for very different reasons. Having surged forward from its bridgeheads on the Vistula, the Red Army had broken into Germany and was approaching the Oder River just to the east of Berlin itself. Successful though the offensive had been, the STAVKA’s plan to defeat Nazi Germany in 45 days had failed, as the troops’ logistics failed to keep pace with their leader’s ambitions. Having splintered Army Group Vistula, under the hapless command of a totally unqualified Heinrich Himmler, the Russians were now short of fuel and ammunition and their attack came to a natural halt. Guderian, probably Hitler’s best remaining general, was the first to see the opportunity for a counter-attack to destroy Zhukov’s overstretched 1st Belorussian Front, and give the Germans much-needed breathing space.

A plan was quickly pulled together that called for a double pincer movement to cut Zhukov’s command in half, a thrust from Stargard in the north meeting up with a southern one from Frankfurt-an-der-Oder. Guderian also proposed that, for the first time in the war, the operation be totally controlled by the Waffen-SS. He called for Dietrich’s Sixth SS Panzer Army to form the southern arm, and a new SS Army, the Eleventh Panzer, to form the northern one. This made sound military sense as it would position Dietrich’s veterans to defend Berlin in the coming battle, but there was now no place at all for sound military thinking on Hitler’s part. The dictator was still obsessed with Budapest and Hungary, never mind that the city had fallen and the country almost lost. He refused to sanction Dietrich’s move north, and insisted the northern thrust alone would be enough.

That blow would be delivered by none other than the man who symbolised more than any other the incorporation of European volunteers into the Waffen-SS – Felix Steiner. Promoted from Corps to Army command, Steiner was now given ten divisions, most of them divisions in name only, and no time to properly organise his staff. Ammunition was low, fuel desperately short and air cover non-existent. Arrayed on a 30-mile front, the attacking force was split into three columns. The Eastern Group was the weakest being made up of the 163rd and 281st Infantry Divisions and the Führer-Grenadier Division, collectively called the Corps Group Munzel after their commander. Their goal was flank protection, and to push out towards Landsberg on the River Warthe. Steiner’s old command, the III Germanic SS Panzer Corps, comprising the Nordland, a Flemish SS battlegroup, the Führer-Begleit Division and the Dutchmen of the Nederland (now upgraded to a division), made up the Central Group under General Martin Unrein. Their mission was to punch south and reach Arnswalde (now Polish Choszno) before advancing further. Completing the counter-attack force was the XXXIX Panzer Corps known as the Western Group. This Corps contained the Army’s Holstein Panzer Division, as well as the 10th SS-Panzer Division Frundsberg, the 4th SS-Panzergrenadier Division SS-Polizei and Degrelle’s Walloons, like the Dutch, recently renamed as a division. Their role was flank protection, as with the Eastern Group, but they were also there to exploit and reinforce any success achieved by the Central Group.

Facing Steiner’s new army were no less than five Soviet ones, including the experienced 1st and 2nd Guards Tank Armies, the 3rd Shock and the infantrymen of the 47th and 61st. With each Soviet Army being roughly equivalent to a German corps in size, it was clear that even if the attacking divisions had been up to strength they would have been badly outnumbered by the Soviets. As it was, their only hope of achieving the three to one ratio all military manuals lay down as necessary for an attacker to ensure success against a defender, was to concentrate all of their combat power into one overwhelming punch. This, Steiner’s inexperienced staff failed to achieve. Confusion reigned in the troops assembly areas, men and vehicles clogged up the few roads, and a thaw made the ground boggy and restricted movement. As a result when H-hour came on 15 February, only the Nordland was ready to cross the start line. They attacked into the northern flank of Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front, but right from the off Soviet resistance was bitter, and the going heavy, as the rain poured down and the ground turned to slush. It wasn’t exactly blitzkrieg. Nevertheless the Scandinavians, Germans and volksdeutsche pushed on, and reached the beleaguered town of Arnswalde on 17 February. Just as with so many towns and villages across the east, the local Nazi Party hierarchy had not prepared the people for the invasion and evacuation was left far too late. Needless to say the ‘golden pheasants’ themselves, as Nazi Party functionaries were disparagingly called on account of their penchant for flashy baubles of rank, managed to escape in time, but for the majority of the populace the swift Soviet advance left them high and dry and at the mercy of a vengeful Red Army.

More than 2000 German soldiers, many of them wounded, had taken refuge in the town and beaten off several determined Soviet attacks while the civilian population cowered in their cellars praying for deliverance. For once that early spring, their prayers would be answered with the arrival of the Nordland’s grenadiers. As the camouflaged and heavily-armed young troopers stormed into town there was a surge of relief as thousands of people poured out into the streets to greet them. Ziegler’s men consolidated for the day and then surged south again, only to hit a veritable wall of Russian steel, as artillery, armour and aircraft fire deluged them. As the SS troopers struggled on, behind them the civilians of Arnswalde packed as many of their belongings as they could onto carts and their own backs and headed north to safety, saved by the Nordland’s advance.

Further gains were impossible, and in a matter of days the now-deserted Arnswalde was again the frontline as the Nordland was pushed back by ever-greater Soviet attacks. On 23 February the town was abandoned. Summer Solstice had failed and the Nordland withdrew back to the line of the Ihna River. So ended the Nordland’s last offensive of the war.

Ultimately unsuccessful as the operation was, Ziegler and the Nordland were commended for their part in the battle. The official report formed part of Ziegler’s citation for the Oakleaves to his Knight’s Cross:

On February 15 1945 the 11th SS-Panzergrenadier Division Nordland, in spite of the severe shortage of fuel and ammunition, began the planned attack to free encircled Arnswalde. Knowing that with the quickly replenished panzer grenadier regiments, the attack’s objective could only be achieved by achieving surprise and leading it personally, SS-Brigadeführer Ziegler and the regimental commanders supervised the deployment for the attack in detail. At the beginning of the attack Ziegler placed himself at the head of the foremost battalion. After breaking the first resistance of the enemy, SS-Brigadeführer Ziegler ordered his armoured group to undertake a violent breakthrough towards Arnswalde.

With further attacks of the panzer grenadier regiments, the enemy [a large part of the 7th Guards Cavalry Corps] was annihilated. Booty included 26 anti-tank guns, 18 heavy grenade-launchers and two batteries of heavy artillery destroyed.

The enemy was defeated by surprise with minimal casualties [one regiment had just seven dead and two wounded] and for the first time an encircled fortress [1,000 wounded, 1,100 troops and 7,000 civilians] was liberated.

Praise indeed, but though casualties were relatively few overall the Scandinavian volunteers were fast becoming a rarity in the Nordland. By the time of the retreat into Courland the division still counted 534 Norwegians in its ranks, this had dropped to just 64 in the Norge by the end of Summer Solstice, and barely a hundred in total throughout the formation. Their places in the ranks were taken by recently-drafted German conscripts and redundant Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine men. Hastily kitted out, these poor unfortunates became so much cannon-fodder, with the Nordland’s remaining veterans providing it with its real combat power.

Solstice had indeed failed, however the Arnswalde relief had unintended consequences for the Germans. Despite all the evidence to the contrary, Stalin and the rest of the STAVKA still feared what the once-mighty Ostheer could achieve, and they were now worried about a more general German assault from the north. They were determined to avoid this by driving to the Baltic Sea on a wide front and crushing all of north-eastern Germany. This would clear their flank, and leave the way open to take Hitler’s hated capital and end the war. While this operation was being hastily planned and executed, the chastened Red Army also pushed west seeking to establish bridgeheads across the last natural barrier between itself and Berlin – the River Oder.