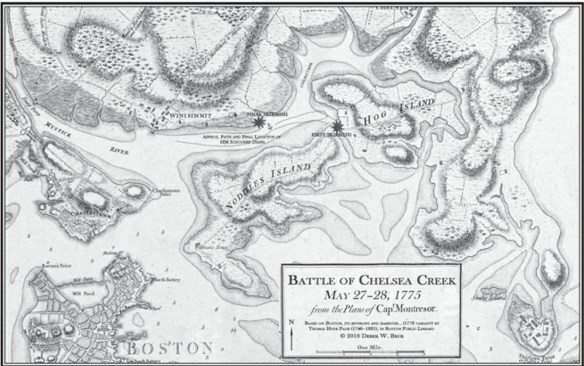

Both adversaries’ reinforcements stormed toward the small inlet that separated Hog Island from Noddle’s, with the Americans on the former and the British on the latter. The odds were now about even, with nearly 150 ground forces on each side, and at last a general fusillade ensued. The British and Americans both ducked for cover in the ruts and ditches of their respective sides of the inlet, while at the same time Diana tried to vie for a better position, coming up to the inlet “as far as there was water” and laying anchor, even as she continued her salvo of 4-pounders and swivels. Behind her, the sloop Britannia hauled in and fired its swivels at the entrenched Americans, adding to the hailstorm that poured onto the marsh.

The marines may have suffered an additional man or two wounded, while the Americans kept safe enough below their cover. Still, one American had a ball fly through his little finger, shearing it off. Another Yankee’s gun backfired, the barrel bursting open and dusting him with burning black powder, melting his skin. But these two and maybe one more were the only Americans wounded, and none of their number was killed.

In this position, with both sides entrenched and firing inherently inaccurate muskets, they found themselves at a stalemate with neither side giving up nor attempting to gain ground. With the sun falling low in the western sky, Captain Chads aboard Cerberus thought he would try to break the stalemate by sending ashore two of his light 3-pounder cannon with a party of seamen. The seamen soon landed and mounted their guns atop a knoll on Noddle’s Hill and began their cannonade, but with little effect.

By six o’clock that evening, the Britannia sloop had broken away from the fight. Lieutenant Graves was determined to back Diana away as well, partly in response to the American onslaught now mostly directed toward his schooner, and partly because of his orders from his uncle the admiral, which explicitly instructed him “not to remain in the River upon the Turn of the Tide”. The flooding tide up Chelsea Creek was sure to hinder Diana’s escape, so Lieutenant Graves complied with his orders and brought her about, hoping to move her back toward Winnisimmet.

But Lieutenant Graves found the winds calm. So he ordered Diana’s one longboat floated, which took aboard it the kedge anchor, and by warping (dropping an anchor ahead and then pulling the boat forward, repeatedly), the crew of Diana fought against the slowly flooding tide and moved her away from Hog Island. Yet the incessant musketry from the Americans, coupled with the flooding tide, made the warping a struggle. At length, as many as seven longboats from the other warships, those that had been used to disembark the fresh marines, rounded Noddle’s Island and joined the effort to haul off Diana, taking lines from the struggling schooner and attempting to tow her by rowing.

The Yankees, meanwhile, seeing the schooner in dire circumstances, turned their entire musketry in that direction, completely ignoring the marines across the inlet. Diana was now turned so that her stern and port side faced Hog Island, her bow aimed northwestward. The perhaps eight longboats were thus ahead of the bow, the schooner herself partially protecting them from the rebel musketry. Nevertheless, the ferocity of the American attack was daunting, and even as the seamen desperately labored to row Diana out from harm’s way, others mounted swivels aboard each boat and fired their half-pound balls back toward shore. At the same time, the marines on Noddle’s Island, seeing the colonial attack had shifted to the vulnerable Diana, moved into a better position, trying to draw away the rebel musketry.

In spite of all the musketry and cannonading, it was mostly just noise, and few on either side were wounded, leaving Diana to slowly make headway westward. By sunset, just after seven o’clock, Diana was well out of range of the Americans on Hog Island. Colonel Nixon then ordered his men to fall back. Nearly out of ammunition, suffering from exhaustion from lack of both sleep and food, and fatigued too from their long fight that had now run nearly five hours, Amos Farnsworth and his fellow New Englanders were only happy to comply. As they left the island, they found that the other half of their force had succeeded in driving all the horses and livestock from Hog Island across to the mainland of Chelsea Neck. If only they had had the means to strip Noddle’s Island of its considerable livestock too, their mission would have been a complete success.

Meanwhile, Diana had moved away from Hog Island, but she was not yet out of danger. As she continued to be warped and towed against the flood of Chelsea Creek, Connecticut Brig. Gen. Israel Putnam appeared on the mainland at the head of nearly three hundred men, perhaps proudly wearing a blue Connecticut militia uniform with red facings, white waistcoat, and breeches.88 Beside him stood Dr. Joseph Warren, the able volunteer who always sought to be at the center of the action, be it political or military. Together they marched the Americans to the marshy shores and lined the riverbank somewhere east of Winnisimmet, drawing near the toiling schooner with their muskets at the ready. Just behind them was the newly formed Massachusetts artillery company under Capt. Thomas Wait Foster, maybe near forty strong. They brought with them two horse-drawn 4-pounders, which they began unlimbering atop the overlooking hills.

The time was approaching eight o’clock, and dusk was quickly dissolving into a dark and moonless night. All was quiet now except for the rhythmic splashing of the oars into the water, the pulling of the hemp lines that stretched from Diana’s bow, and the sounds of the struggling seamen. Neither side had yet fired, but both adversaries sized up one another. Lieutenant Graves, aboard Diana, privately admitted that his towboats had gained him little ground. Toiling as they were against a contrary flood tide, failed as they were by the wind, and seeing too a fresh colonial force on the nearby shore, the hapless young naval officer knew his chances for escape were slim. On shore, Putnam knew it too, so he decided to offer Lieutenant Graves a way out. He stormed down to the creek’s edge and sloshed into the muddy water, yelling to the schooner’s crew and to the rowboats: if they would submit, they should have quarters. Diana’s crew looked to Lieutenant Graves for the reply. All was quiet for a moment.

The fresh colonial troops waited along the north side of the riverbank in anticipation. Suddenly, two of Diana’s starboard cannon erupted with thunder, belching forth white smoke and flame, spitting two cannon shot that whizzed by Putnam and dispersed the Americans. Lieutenant Graves had given his reply, and the American cannon immediately fired two return shots into Diana. All along Diana’s starboard gunwales and stern, the swivels came alive once more.

Putnam put his men “up to their waists in water, and covered by the bank to their necks.” There they immediately joined the chorus of cannon, giving a scattered bombardment across Diana and her towboats. Perhaps the 150 marines still on Noddle’s Island also fired a few useless volleys from that long range across Chelsea Creek. Certainly, the two 3-pounders from Cerberus, still mounted on Noddle’s Island, joined with their own cannonade.

Seeing the battle again renewed, General Gage in Boston sent over some of his own artillerymen with two heavy 12-pounders, along with a fresh body of one hundred to two hundred of his marines. The artillerymen soon mounted their 12s alongside the naval 3-pounders on Noddle’s Island, but with twilight nearly faded to utter darkness, they could provide only harassing fire. The new marines there could do nothing.

Aboard the longboats, a few seamen again manned the swivels, firing at an unseen enemy obscured by the dim shoreline. The rest ducked low to avoid the whizzing balls overhead, even as they continued to row helplessly against the tide. Here it seems the British took the most casualties, with several wounded both in the schooner and the boats. On the American side of the fight, Putnam encouraged his men, urging them not to fear the wayward cannon balls and musketry, all of which failed to hit their mark.

As the two sides continued with renewed ferocity, the last glimmers of light finally faded from the sky. The cannonade and musketry soon became sporadic, for all one could do was shoot in the direction of the orange, fiery blasts spewing from the opposing guns. The darkness forced Putnam and his men to leave their tide-pool ditches and wade deeper into the creek itself, striving to draw near enough to make out the dark vessel and her boats. So the battle continued even in the darkness, though with far less intensity. Yet under such fire, the valiant seamen persevered until, at last, nature intervened. At about half past ten o’clock on that moonless night, the flood tide having crested, the waters of Chelsea Creek slowly began to ebb once more.

Now Lieutenant Graves had his opportunity, because the gently ebbing tide was advantageous to his escape. He ordered the boats to cast off, and once they had, Diana began to drift away from the battle westward toward Winnisimmet. No sooner had she begun to ride the current away than a contrary fresh breeze sprung up from the southwest, and with the fresh ebb tide not strong enough to counter it, Diana lurched sideways toward the rebels pursuing along the riverbank. Before Diana’s crew could regain control, “five or 6 Minutes would have secured her”, she drifted into the shallow banks of the mainland near the Winnisimmet Ferry Way, running aground about 180 feet from the shore at around eleven o’clock.

The sailors in the nearby longboats quickly rowed near and again took the towlines to try to free Diana, but the Americans concentrated all their firepower on them, enfilading the vessel and her boats. The provincial cannon meanwhile homed in on the schooner in the darkness, until it at last found its mark and began blasting holes into her starboard side. The sailors struggled hard to break Diana free, but soon the creek was fast ebbing away, forcing many sailors to hop from their boats and wade in the waters abeam her, braving the sporadic musket fire to push on Diana’s hull by hand and floundering in the mud as they tried desperately to float her.

For the British sailors, the Battle of Chelsea Creek became not one of defeating the Americans but of saving the schooner. Some aid came from the sloop Britannia, which again drew near, courtesy of the fresh breeze, and so provided cover fire with her complement of swivels. For hours, the sailors struggled beside Diana even as the Americans continued to harry them with sporadic musketry despite the darkness, all while both sides blindly cannonaded one another. Yet there was little more the British could do. With the creek continuing to ebb, the water soon fell below the seamen’s knees as they floundered and pressed against the hull. At near three o’clock in the morning, Diana began to lurch once more, then totter, and at last fell on her beam-ends, her obstinate but valiant crew jumping or falling off her deck as she keeled over.

On her side, Diana could no longer be manned, nor her guns fired. All the sailors could do was use the hulk as one giant shield from the American musketry while they awaited rescue. There in the shallow, ebbing, muddy water behind Diana, the officers and seamen took cover before wading over to the nearby Britannia and the longboats, at last abandoning their schooner. Once they climbed aboard, the British boats rode the ebb tide away to safety, even as the water around Diana drained entirely away, leaving her beached on the expansive mudflats.