When the three newly arrived major generals disembarked from Cerberus and came to Province House, they found His Excellency Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage busy with another urgent matter. Courtesy of his secret spy network, Gage had learned that the rebels were planning to sneak onto nearby Noddle’s Island that night and destroy or carry off all the livestock thereon, “for no reason but because the owner having sold them for the Kings Use”. This owner was Henry Howell Williams, and though he was a dedicated Whig whom Admiral Graves called “a notorious Rebel”, he was also a merchant, and the lure of profit habitually enticed him to sell his diverse livestock and poultry to outbound British vessels.

Since the Grape Island affair, Gage had been worried about access to the few remaining friendly farms on the various harbor islands and, on May 25 1775, had successfully raided nearby Long Island for additional hay. The Americans meanwhile had turned their attention to the abundant stocks on Noddle’s Island and adjacent Hog Island, which they feared could feed the British for some time and thus negate their Siege of Boston.

In fact, the Americans had been pondering the removal of those livestock for a month. On May 14, the Committee of Safety had advised the selectmen of the coastal towns to consider removing the stock from those islands. When the towns did nothing even in the wake of the raid on Grape Island, the Committee of Safety resolved on May 24 to press the Provincial Congress to immediately clear those islands. It was this resolution that was transmitted to Gage through his spy network by early May 25, perhaps passed by word of mouth via Dr. Church’s go-between when they delivered Church’s latest intelligence. In response, Gage wrote a hasty letter to Admiral Graves, urging the naval commander to order his “guard boats to be particularly Attentive, and to take such Other Measures as you may think Necessary for this night”.

Graves, meanwhile, was busy sorting through the dispatches just received from HMS Cerberus, including one explaining the almost unenforceable Restraining Act lately passed by Parliament. With it, the burden fell upon the admiral to somehow prevent New England vessels from accessing the Newfoundland fisheries and from trading to any sovereign besides Britain. Also among the dispatches just received, Vice Admiral of the Blue Samuel Graves joyously discovered an official notice of his promotion, dated April 13, giving him the new rank of Vice Admiral of the White. Graves apparently decided to keep his new appointment to himself for a day, but it was with this pleasure that he received Gage’s urgent appeal.

When Graves read Gage’s hasty letter, his first thought was not of the livestock, but of a storehouse there of lumber, boards, and spars intended for repairs of his vessels. “The preservation of all these”, he later wrote, “became of great consequence, not altogether from their intrinsic Value, but from the almost impossibility of replacing them at this Juncture.” It was thus with a different agenda that the admiral promptly replied to the general, affirming, “The Guard boats have orders to keep the strictest look out; and I will direct an additional One to row tonight as high up as possible between Noddles Island and the Main”. Graves suggested that the best course of action, however, was to station a guard on the island. Accordingly, about forty marines, perhaps drafted from those of the warships, were sent to Noddle’s Island and barracked in Henry Williams’s hay barn.

That night, all was quiet. But the next morning, May 26, the American siege lines were startled to attention when they heard a sharp cannonade across the harbor. At eight o’clock, the HMS Preston crew lowered the blue admiral’s flag from the ship’s fore-topmast and raised in its place the flag of St. George’s Cross, the famous English white flag with a red cross, while at her stern the crew replaced her blue ensign with the white equivalent, thus formally signifying Vice Admiral Graves’s promotion from Blue to White. Noting the change aboard their flagship, the squadron throughout the harbor likewise exchanged their stern ensigns and then each fired thirteen cannons in salute, to which Preston returned thirteen.

The rest of the day came and went without incident. It was not until late that evening when Massachusetts Col. John Nixon received his orders and so mustered a detachment of between two hundred and three hundred. Together they marched from their camp in Cambridge through Mystick (now Medford), Malden, and Chelsea, where they waited until dawn, whose radiance began to brighten the sky at nearly four o’clock on May 27.

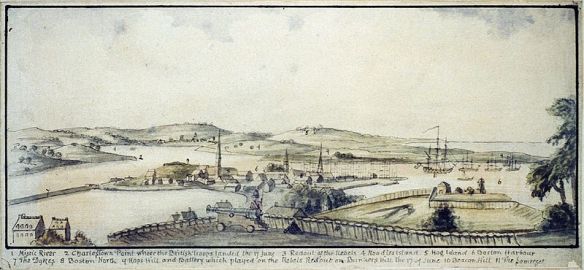

The topography of the islands is difficult to make out today, as most of the old tidal zones and mudflats have been filled in, making both Noddle’s Island and Hog Island now part of the mainland. North of the two islands ran Chelsea Creek, still extant, which separated the islands from the mainland, where the small Chelsea parish of Winnisimmet (now simply Chelsea proper) once stood. To the west and south was Boston Harbor, with Boston itself just across a narrow expanse to the west. To the east, the two islands were further separated from the mainland by narrow Belle Isle Inlet, as it is now called, which at low tide became an easily fordable, knee-high creek with wide mudflat banks. The two islands themselves were separated by an equally thin, shallow inlet, unnamed and since filled in. The mainland just east of the islands was the rolling heights known then as Chelsea Neck, now the south end of Revere before entering Winthrop. It was from there on the eastern heights that the Yankees forded Belle Isle Inlet at near ebb tide and so marched onto Hog Island.

By noon, the Yankees began herding off the 6 horses, 27 horned cattle, and 411 sheep from the Hog Island farms of Whigs Oliver Wendell of Boston and Jonathan Jackson of Newburyport. They did not immediately cross to Noddle’s Island, presumably waiting both for a lower ebb tide and for the mission to make headway on the present island before stirring up the British encamped on the other. It was not until around one o’clock that afternoon that the Americans finally forded the unnamed creek over to Noddle’s Island.

Maybe just thirty Americans crossed, including Amos Farnsworth. The gentle hill centered on Noddle’s Island afforded them some semblance of cover from the British marines situated on the opposite side of the island. Well aware of the marines, Farnsworth and his fellow Yankees crept along the pastures. They spotted the large herd of grazing sheep and lambs, intermingled with handfuls of horses and horned cattle, amounting to nearly a thousand livestock. With such a large herd and with the marines so close, the Yankees knew they could not expect to remove many of the beasts.

Since their raid could do nothing more than harass the British, they decided to kill what animals they could and steal away still others. Yet once they fired that first shot, the marines would be on them in moments. They agreed they had but one chance to make the most of their raid. Daringly, they crept farther into the outlying pastures of the Williams farmstead until they reached a large barn “full of salt hay” (salt meadow hay or marsh grass), which stood next to an old and abandoned farmhouse. As the afternoon approached two o’clock, the Americans prepared makeshift torches, likely using their musket flints and some of the dry salt hay to do so. They then looked at one another, each with a lit torch in one hand and a musket in the other. Finally, perhaps with a nod, they threw their torches into and onto the barn and house, then quickly turned and fled. As the two wooden structures instantly took fire, billowing dark, gray smoke into the air and so drawing the attention of the marines across the field, the Americans fired their muskets at nearby horses and cattle, killing many before grabbing others to steal away.

The marines may have hesitated for a moment, unsure what was happening, but the smoke and the musketry immediately made the situation clear. Their response was quick. They gathered their guns and charged toward the fleeing Americans, giving a scattered volley of musket shot as they did so. The Americans managed to slaughter some fifteen horses, two colts, and three cows, and even with the marines in hot pursuit, they now wrangled two fine English stallions, two colts, and three cows away. The remainder of the stocks would have to wait for some future raid. The Americans rushed their herd of seven beasts eastward toward adjacent Hog Island, the marines hot on their trail.

With the skirmish afoot, the crew aboard HMS Preston in Boston Harbor took notice of both the conflagration and the billowing white smoke from the scattered musketry. Admiral Graves ordered the signal for the landing of marines, to which a sailor gathered a prearranged signal flag and promptly hoisted it up one of the masts of the flagship. As the signal flag was raised, Preston fired a cannon, alerting the other warships of their new orders. It only took moments, but soon all of the men-of-war were floating their longboats full of marines.

Graves next issued orders for the newly purchased and outfitted schooner Diana, under the command of his nephew Lt. Thomas Graves. The vessel was anchored near the path of Winnisimmet Ferry, between Winnisimmet and the north side of Noddle’s Island, an ideal position to aid in the skirmish, but far enough from Preston that a midshipman courier must have been sent by rowboat to Diana to convey the orders. Once they were received, Diana’s crew of thirty began to scurry across the top deck, some weighing her two bower anchors as others unfurled and trimmed her sails. Within moments of receiving her orders, the two-masted schooner was sailing swiftly along Chelsea Creek to the northeast side of the island.

With the British reinforcement on its way and the marines on Noddle’s Island in pursuit, the Yankee raiders soon reached the inlet separating them from Hog Island. But no sooner had they reached it, near three o’clock, than Diana bore down on them, unleashing a hailstorm of cannon shot from its four 4-pounders and twelve swivel guns. “But we Crost the river and about fifteen of us Squated Down in a Ditch on the ma[r]sh and Stood our ground”, according to Amos Farnsworth.78 Perhaps the other fifteen Yankees led their seven stolen livestock farther onto Hog Island, leaving Farnsworth and his fellows to cover their retreat. With the schooner bearing down on them, keeping the Americans pinned in their marsh ditch, the marines from Williams Farm caught up to the fight.

The marines took up position across the narrow and shallow inlet from the Americans and their first platoon fired before falling back to reload, leaving the next platoon in the front position to then fire. While the marines continued to fire in platoons, Farnsworth and his fifteen fellow Americans popped out of their cover and gave a volley, killing or wounding a marine or two. The marines continued to fire back with ferocity. As Farnsworth put it, “we had A hot fiar… But notwithstanding the Bulets flue very thitch [thick] yet thare was not A Man of us kild.” No American died perhaps, but just as one Yankee near Farnsworth popped up to shoot, a marine took aim and fired, the lead ball smacking through one end of the Yankee’s fleshy cheek and out the other, missing the bone, but instantly drawing blood that spurted down his chin and onto his collar.

As these few Americans found themselves pinned down, both sides expected reinforcements. The several British longboats from HMS Somerset, HMS Glasgow, and HMS Cerberus had all streamed toward the island and were now disembarking a combined total of nearly a hundred additional marines. The Glasgow also sent her pinnace and Somerset sent her small sloop tender Britannia, each armed with swivel guns. On the American side, maybe half of the more than two hundred Americans still on Hog Island began to descend toward the battle, while the remainder continued to remove the herds to Chelsea Neck.