If American soldiers in Vietnam found little meaning from the ongoing war, Hanoi’s general secretary of the Central Committee did not share their views. True, Le Duan faced a host of challenges in mid-1970. The Sino-Soviet split had damaged Hanoi’s relationship with Beijing. Morale of the North Vietnamese population seemed to be slipping, requiring a police crackdown against any antiwar sentiment. Within the Politburo, Le Duan met with increased criticisms of his military policies. At the Central Committee’s Eighteenth Plenum, held in January, delegates pushed through a final decree pronouncing that North Vietnam “must answer enemy attacks not only with war and political activity but also with diplomacy.” In a rebuff to Le Duan’s aim of achieving a decisive battlefield victory, the declaration argued that terminating the American presence and support to the Saigon regime would come from more than just military action. The stalemated war had convinced Le Duan’s opponents that diplomacy, backed by the use of force, offered the surest path to resolving the question of Vietnamese independence.

Yet the war still mattered and thus still held meaning. Similar to Nixon’s White House, the conflict had become for Hanoi a question of balancing the demands of the political and military struggle with the wrangling of high-level diplomacy. Le Duan might have his critics, but all senior North Vietnamese leaders agreed on the ultimate aim of national sovereignty and freedom from external influence.

Of course, the American war had exacted a heavy price. Two years after its launch, the failed 1968 Tet offensive still cast a long shadow over the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and, especially, the National Liberation Front (NLF). Le Duan poured resources and manpower into the military recovery effort, prompting opponents to charge he was setting back the DRV’s own social revolution. Americans, for their part, claimed the 1970 Cambodian incursion had derailed Hanoi’s plans for a summer offensive that year. Captured documents, however, indicated that North Vietnamese leaders held no such designs. In fact, at the opening of 1971, Kissinger forwarded a report to the president highlighting “a major U.S. intelligence failure” in evaluating the value of Cambodian ports to the communist war effort. The enemy’s logistics network had proved more extensive than previously assessed, a miscalculation resulting “from deficiencies in both intelligence collection and analysis.” If the war had taken a toll on Hanoi, US analysts remained uncertain by how much.

This ambiguity resulted, in part, from the changing nature of the communist threat after more than a decade of war. While Nixon and his advisors maintained watchful eyes on an enemy buildup in Laos at the end of 1970, US leaders in South Vietnam perceived a slackening of communist influence in the countryside, most notably in the Mekong River Delta region. Military correspondent William Beecher, though, questioned whether “this gain is real or illusory,” and even optimists pointed out that the “current calm and unparalleled prosperity” did not “end the problem.” While the revolution waned in some areas of South Vietnam, NLF cadre remained committed to defeating the “American aggressors.”

Moreover, intelligence analysts still struggled to accurately assess the amount of political dissension within the local population, the damage being done by partisan bickering in Saigon, and the potential impacts of a negotiated cease-fire. Hanoi’s decision to elevate the diplomatic struggle seemed only to further complicate an already convoluted political-military struggle.

The ongoing US troop withdrawals undergirding Nixon’s Vietnamization policy added yet another element to the dizzying array of factors swaying the course of the war. Creighton Abrams, for one, doubted whether the Saigon government could compensate for the diminishing American support. Near the end of 1970, the MACV commander expressed his private concerns over the loss of “adequate intelligence support” for the South Vietnamese armed forces. More importantly, the “acceleration of [the US] redeployment,” Abrams cautioned Pacific Command’s Admiral John S. McCain Jr., “provides the enemy increased freedom of movement and enhances his capabilities and opportunities to significantly interfere with and disrupt pacification and Vietnamization programs.”

Thus, with the United States committed—for most observers, irrevocably—to a withdrawal from Indochina, a major question arose. At what point would American military and civilian leaders fully lose their leverage over the course of events inside South Vietnam? The US nation-building effort had always been a bargaining process, a compromise between the Saigon policy elite and American advisors. By late 1970, however, it appeared as if Abrams and Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker were reacting to events more than commanding them. Even the early 1971 ARVN incursion into Laos suggested an uncomfortable loss of control on the military battlefield. Furthermore, as US ground troops continued their departure from the war-torn country, the threat of coercive airpower seemed, at best, a weak substitute for the prospects of nation building.

The strategic guidance imparted by Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird highlighted the inherent problems with maintaining leverage as the American withdrawal progressed. Laird emphasized four goals for MACV in 1970: successful Vietnamization, reduction of US casualties, continued troop withdrawals, and stimulation of meaningful negotiations. Logically, Vietnamization meant strengthening the ARVN, thus accelerating progress in the war effort. In reality, none of these objectives facilitated the larger aims of defeating “externally directed and supported Communist subversion and aggression.” Nor did they aid the South Vietnamese people in determining their future “without outside interference.” Moreover, the 1971 Combined Campaign Plan changed the basic role of US forces. Instead of conducting operations, they would now “support and assist” their South Vietnamese counterparts.

It seems plausible to argue, then, that by late 1970, Creighton Abrams no longer shaped the strategy of the war he was still waging in South Vietnam. His influence, both in Washington, DC, and in Saigon, was clearly waning. Increasingly over the next two years, the president and senior White House advisors would become “particularly critical” of Abrams, Nixon even complaining that the general did not “think creatively.” On two occasions, MACV’s commander nearly lost his job. Meanwhile, South Vietnam’s president sought to distance himself from the departing Americans even as he hoped to secure promises of continued aid for a struggle likely to endure after the last US troops went home.

If Abrams failed to command events on the ground in the war’s final years, he should not bear sole responsibility for the allies’ ultimate lack of success. Surely, the White House had given its principal military commander in Vietnam an unrealistic mission. As a staff study published by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1970 illustratively concluded, “The assumptions on which American policy are based are ambiguous, confusing, and contradictory.” Additionally, Abrams came to realize a hard lesson discerned by previous US military leaders in Vietnam. There quite simply were limits to what American power could achieve in a war that preceded US intervention and would continue long after foreign troops withdrew.

Thus, it seems wrong to assume that Abrams truly fought a war any better than those commanders who came before him. It is even harder to conclude that a war already won in mid-1970 would now be lost by weak politicians at home with no stomach to see the conflict through to its rightful conclusion.

An Expanding War Once More

A resurgent Congress disquieted senior military leaders just as much as, if not more so than, the president. At MACV headquarters, Creighton Abrams watched the unfolding political drama with visible unease. Back in 1968, not long after assuming command, the general had thundered to his staff that it was “really shocking how these politicos in the United States go charging around like a bull in a china shop saying what ought to be done out here politically. God Almighty!” The ongoing debates on Capitol Hill did little to soothe Abrams’s temper. While the House considered the second Cooper-Church amendment, MACV’s commander proposed expanding the war once more, this time with military action against suspected NVA anti-aircraft sites in Laos. The recommendation would prove a harbinger of the civil-military friction endemic in the final two years of the American war.

To at least some observers, the stalemated conflict had also battered, if not nearly broken, the MACV commander. At fifty-six, Abrams had been in South Vietnam for more than four years by late 1970. His health had suffered. Hospitalized three times that year, once to remove his gall bladder, the general had lost weight and a supportive Laird quietly began lobbying for Abrams to replace Westmoreland upon his retirement as the army’s chief of staff. When Frederick C. Weyand pinned on his fourth star in early November, speculation rose that MACV’s deputy commander might take over the war as early as spring.

Abrams, however, had his hands full and left such conjecturing to the press. As 1970 drew to a close, the MACV staff convened special meetings to discuss intelligence reports of a new North Vietnamese buildup in Laos. Though large-scale operations had decreased inside South Vietnam, MACV analysts noted “an increase in terrorism and small-unit harassing actions.” More troubling, however, infiltration of major NVA units appeared along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, forcing Abrams to request a delay—leaked by “Pentagon sources”—in further troop withdrawals. The leak failed to impress the secretary of defense. Upon his return from Saigon in early 1971, Laird declared, according to the New York Times, that “South Vietnamese forces were improving so rapidly that ‘additional thousands’ of American troops could be withdrawn this year.”

The apparent contradictions between MACV estimates and Laird’s optimism stemmed from the continuing inability of American analysts to accurately predict Hanoi’s next strategic move. It made sense for North Vietnamese leaders to avoid expending scarce resources with approximately 50,000 US troops departing every six months. Some Politburo members even suggested that persistent military pressure might slow down rather than hasten American withdrawal timelines. Still, Abrams’s staff watched nervously as regiments from the North Vietnamese 312th Division returned to southern Laos after an apparent six-month absence. If Hanoi leaders had decided 1971 to be a year of transition rather than military offensives, the Laotian buildup, coupled with diplomatic intransigence in Paris, persuaded Abrams and his key subordinates of the need for preemptive action.

Thus, while American warplanes continued their assault against the Ho Chi Minh Trail, MACV began advocating for a cross-border military operation into Laos. Abrams had long been promoting such ideas. Westmoreland, responding to his West Point classmate’s proposal for an assault into the Laotian panhandle back in 1965, had explained that an incursion “was not in the cards for the foreseeable future because of complex political and other considerations.” No doubt, both senior officers resented these political restrictions but Westmoreland knew his place. Moreover, Americans had been quietly operating inside Laos since the early 1960s, conducting “shallow penetration raids,” probing operations, and air strikes. By 1968, US special operations teams were working inside the “neutral” country, hoping to develop a “native intelligence net” in the southern panhandle of Laos that had become “dominated by North Vietnamese forces.”

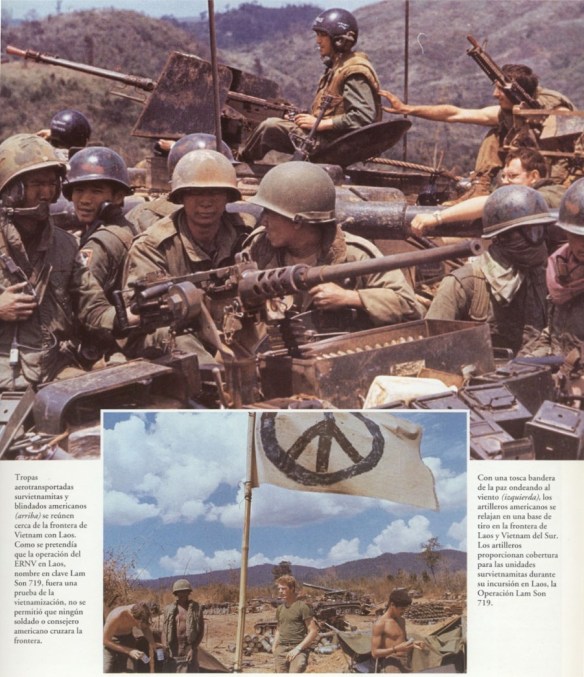

These initial forays into Laos only whetted the appetites of military brass who believed the success of Vietnamization depended on a “preemptive defensive raid” against NVA enclaves just outside of South Vietnam’s borders. At the White House, Alexander Haig endorsed Abrams’s proposal to employ two ARVN divisions to sever enemy lines of communication inside Laos, a “potentially decisive” operation according to MACV’s chief. Abrams also worked on winning over the Joint Chiefs. Not surprisingly, the service chiefs were an amenable crowd. At the Pentagon, Haig advocated on the MACV commander’s behalf, recommending “authority to use the full range of US air support, to include tactical and strategic bombing, airlift and gunships.” Congress may have prohibited the use of ground troops outside Vietnam, but Abrams still had a deadly arsenal to which he could turn.

Thus, military leaders once more viewed an offensive outside South Vietnam’s borders as a way to bolster Vietnamization. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Thomas H. Moorer argued in late January 1971 that disruption of the NVA logistics hub at Tchepone in Laos would do more than simply increase the Lon Nol regime’s chances of survival. The admiral claimed the operation would also “drastically delay the infiltration timetable for [enemy] personnel, facilitate Vietnamization in South Vietnam, and insure our ability to continue with a rapid rate of withdrawal of U.S. forces.” Though Abrams confessed the South Vietnamese did not have the capacity to support themselves in Laos, Moorer believed US command of the air would more than compensate for the ARVN’s deficiencies. “If the enemy fights, and it is likely that he will,” the chairman declared, “U.S. air power and fire power should inflict heavy casualties which will be difficult to replace. The enemy’s lack of mobility should enable us to isolate the battlefield and insure a South Vietnamese victory.” The coming weeks would prove Moorer an unreliable soothsayer.

The decision to support a Laotian operation, however, rested on more than proving the tenability of Vietnamization. For Nixon, a military offensive could demonstrate, in dramatic fashion, his continuing control over events. By giving “the NVN a bang,” the president could advance his objective of “an enduring Vietnam, namely, one that can stand up in the future.” Moreover, the operation “provided insurance for next year when our force levels would be down.” Critics worried about “slipping into a wide-ranging air war that could last almost indefinitely,” but Nixon thought the benefits far outweighed the risks. His cabinet even pointed to the Nixon Doctrine as a justification for widening the war once more. To the Senate Armed Services Committee in early February, Secretary of Defense Laird defended the use of “sea and air resources to supplement the efforts and the armed forces of our friends and allies who are determined to resist aggression, as the Cambodians are valiantly trying to do.”