Tensions between France and England ignited in 1754 when an expedition led by a young George Washington attacked and killed a French diplomat near Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh). Retreating to a nearby meadow, Washington built a palisade fort, Fort Necessity, and awaited the retaliatory force composed of the French and their Indian allies. Ignoring the advice of his Indian ally to ambush them while they were approaching, Washington instead chose to fight in the open and anticipated the French would do the same. Instead the French and Indians remained in the woods and picked off Washington’s Virginians. They fought back the best they could but when ammunition ran low and casualties mounted, Washington had to surrender. Washington unwittingly signed surrender terms that admitted that he had assassinated the French diplomat. In the wake of these incidents, a world war erupted that was fought not only in North America but also in the Caribbean, Europe, and India.

To recapture Fort Duquesne, Britain dispatched General Edward Braddock along with two regiments: the 44th East Essex and 48th Northamptonshire. Totaling 1,440 officers and men, they were supported by Washington’s 450 colonials. Within a short march of Fort Duquesne, Braddock’s column collided with a force half their size composed of French marines, Canadians, and their Indian allies on the Monongahela River. Standing exposed in their linear formations, the British fired off volleys as the Canadians and Indians melted into the woods. Indian fighting tactics were adapted from communal hunts and this enabled them to coordinate their attacks even when multi-tribal groups fought alongside one another.

Applied in warfare, they enjoyed a mobility unsurpassed by any European army. Using their field craft, they seemingly disappeared only to suddenly reappear elsewhere to pick off an opponent. After four hours of fighting and having seen many of their comrades and officers shot, panic spread among the ranks and men began to flee in terror. Those who stood their ground poured un-aimed volleys into their comrades or the air while the Indians hid behind bushes, trees, rocks or in depressions in the ground. The proud little army that had marched confidently into the wilderness suffered 46 percent casualties, with 456 killed and 421 wounded. Braddock was mortally wounded, remarking before dying, “We shall better know how to deal with them another time.”

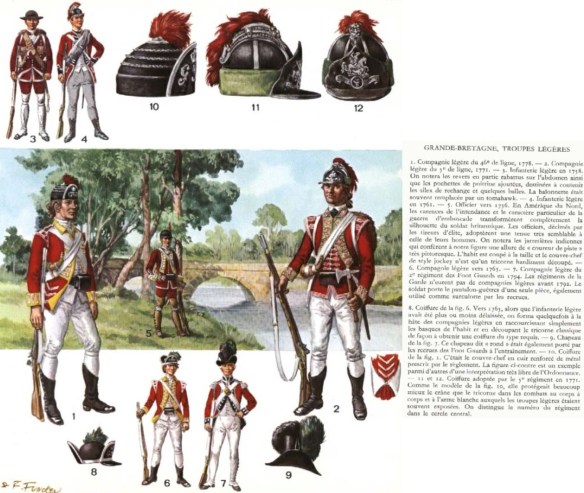

Blame can neither be placed totally on the soldiers nor Braddock since no formal training of the period could prepare them for forest warfare. The lessons were not lost and the British army began adapting itself by raising light infantry and, from among the colonists, rangers who would scout and screen the army better. Men were taught to seek cover (“Tree all”) and to aim at marks. Before the war, linear formations ensured an officer of his command and control over his men and they were loath to depart from the practice. Adopting open formations was quite a novel concept. Finally a limited number of rifles were distributed.

Results were not immediate but during the landing to capture Louisbourg in 1758, the 78th Fraser Highlanders came under fire. Sergeant Thompson recalled the incident:

During the landing at Louisberg there was a rascal of a savage on top of a high rock that kept firing at the Boats as they came within his reach, and he kill’d volunteer Fraser of our Regiment who, in order to get his shilling instead of six pence a day, was acting, like myself as a sergeant, he was a very genteel young man and was to have commison’d the first vacancy. There sat next to Fraser in the boat, a silly fellow of a Highlander, but who was a good marksman for all that, and not withstanding that there was a positive order not to fire a shot during the landing, he couldn’t resist this temptation of having a slap at the Savage. So the silly fellow levels his fuzee at him and in spite of the unsteadiness of the boat, for it was blowing hard at the time, ’afaith he brought him tumbling down like a sack into the water as the matter so turned out, there was not a word said about it, but had it been otherwise he would have had his back scratch’d if not something worse.

After landing, 550 of the best marksmen were drawn from the available units and organized into a provisional light infantry battalion. As sharpshooters, they suppressed the defenders during the construction of the siege works. After the siege guns were mounted in the third parallel, Louisbourg surrendered.

Sergeant Thompson survived and became part of the garrison of Quebec after its capture by General James Wolfe. In the spring of 1760, when a French force arrived to retake it, the reduced British army marched out to meet it. They were defeated and began to retreat to the safety of Quebec’s walls. One French column threatened to cut off the retreat and Thompson recalls the shot that prevented it:

On the way I fell in with a Captain Moses Hazen, a Jew, who commanded a company of Rangers, and who was so badly wounded, that his servant who had to carry him away was obliged to rest him on the ground at every twenty or thirty yards, owing to the great pain he endured. This intrepid fellow observing that there was a solid column of the French coming on over the high ground and headed by an officer who was some distance in advance of the column, he ask’d his servant if his fuzee was still loaded (the Servant opens the pans, and finds that it was still prim’d). “Do you see,” says Captain Hazen, “that rascal there, waving his sword to encourage those fellows to come forward?” “yes,” says the Servant, “I do Sir.” “Then,” says the Captain again, “just place your back against mine for one moment, till I see if I can bring him down.” He accordingly stretch’d himself on the ground, and resting the muzzle of his fuzee on his toes he let drive at the French officer. I was standing close behind him, and I thought it perfect madness in his attempt. However, away went the charge after him, and ’afaith down he was flat in an instant! Both the Captain and myself were watching for some minutes under an idea that “altho” he had laid down, he might take it into his head to get up again, but no, the de’il a get up and did he get, it was the best shot I ever saw, and the moment he fell, the whole column he was leading on, turn’d about and decamp’d off, leaving him to follow as well as he might! I couldn’t help telling the Captain that he had made a capital shot, and I related to him the affair of the foolish fellow of our Grenadiers who shot the Savage at the landing at Louisberg, altho’ the distance was great and the rolling of the boat so much against his taking a steady aim. “Oh,” says Captain Hazen, “you know that a chance shot will kill the devil himself!”

Captain Hazen survived and rose to brigadier general in the Continental Army during the Revolution.

The French were obligated to form one regiment, in their line, directly facing this wood, where the jägers were stationed. The jägers made such havoc amongst this French regiment, that the colours were at last forced to be held by serjeants, and even corporals. There were but very few of their officers who were not killed or wounded. The jägers were not above two hundred yards from them, and were flanked, both on their right and left, by strong battalions of the line. The French were at last compelled to bring up six pieces of cannon, loaded with grape, to clear the woods of jägers. I had a man in my company, in the Hessian jägers, in America, who was the son of a jäger, supposed to be one of the very best shots among those engaged at Minden. His comrades had such an opinion of his shooting, that six or seven men handed their rifles to him, as he stood behind a large tree, continually keeping them loaded for him to fire, so that he could fire several shots in one minute. When the cannon were brought up, his comrades desired him to come away; but he said he would stay, and have one shot more; a grape-shot struck him, and killed him. The French were so incensed that day against the jägers, that a few of them which they took, wounded, in the retreat, for the German forces were beaten, they buried up to their chins in the ground, and left them to die.

While the rifle was slowly gaining acceptance as a specialized weapon to be used by light troops, the war’s conclusion did not see its universal adoption. The British Army returned its rifles to storage at the war’s conclusion and for the most part, forgot the lessons learned.