Barry Spicer is a celebrated aviation artist from Adelaide, Australia. Barry considers himself lucky to be able to do something he loves, and his fascination in aviation goes back to his childhood. At the age of 6, his parents took him to see the film “The Battle of Britain” and was so inspired by the sight of the graceful but deadly aeroplanes that he turned his already established pastime of drawing to aircraft. Since then he has been fascinated by flight and just about anything that flies which is evident in his finished works, be they drawings or oil paintings.

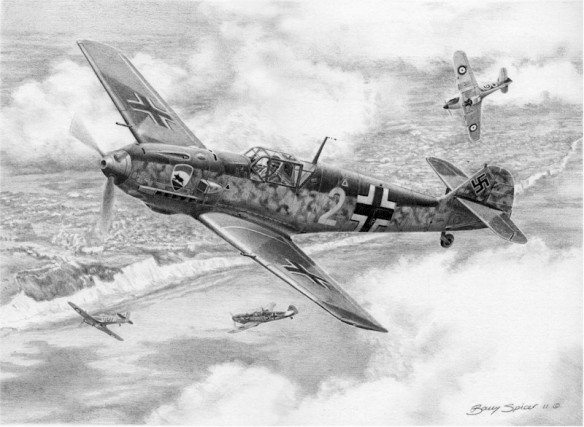

This recent work entitled “Combat Over the Channel” captures a dramatic Battle of Britain dogfight between a pair of Bf 109s and Hurricanes over the Channel coastline.

The largest attack to date was carried out by waves of He111s – 16 of I/KG27, 12 of II/KG27, 12 of III/KG27 and 10 of I/KG4, 11 of II/KG4 and 10 of III/KG4 – on the night of 18/19 June, the Home Office Intelligence Summary revealing the extent of the raids and the damage inflicted during the period 18:00 on 18 June to 06:00 on 19 June:

Coastal districts from Middleborough to Portsmouth were under warning and sirens were sounded in Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Huntingdonshire and Kent during the night. London was under yellow warning during the period, and so was the Barrow-in-Furness district on the South-West Coast. Some bombs dropped in the North-Eastern Region, and, a substantial number in the North Midland Region; the chief damage, however, was done at Cambridge, where houses were demolished and nine people were killed, at Southend, where houses and a boys’ school were damaged, and to oil installations Canvey Island. Incendiary and high explosive bombs were used. Ten civilian deaths [in total] and 26 people injured have been reported.

KG27 headed for the Midlands while East Anglia bore the brunt of KG4’s raids as bombers targeted RAF stations in Suffolk and Norfolk. Warned of the approaching enemy aircraft, Blenheim night fighters of 29 Squadron from RAF Debden were ordered off, while a lone Spitfire of 19 Squadron flown by Flt Sgt Jack Steere was scrambled from RAF Duxford at 23:15. At about the same time more Blenheim night fighters of 23 Squadron were taking-off from RAF Wittering. Heinkel 5J+GA of Stab/KG4 flown by Ltn Erich Simon with Oblt Heinz-Georg Corpus as observer led the way on a pre-attack reconnaissance, and was followed by the main force flying in sections at intervals. The first of these reached Clacton at 23:00, and 15 minutes later another was illuminated by searchlights, at which the crew released their bombs. Three exploded in nearby Holland-on-Sea, damaging houses in King’s Cliff Avenue and Medina Road. Another Heinkel jettisoned its bombs over Southend, where one of the thirteen casualties later died. By now the leading section of three Heinkels was approaching Bury St Edmunds, but east of the Suffolk market town they were intercepted by a Blenheim of 29 Squadron flown by Sqn Ldr John McLean. They proved too fast for the Blenheim, one Heinkel opening fire on its pursuer without effect. This, or another, jettisoned its bombs, which fell at Rougham Rectory and near its churchyard.

Another Staffel crossed the coast at Sheringham, near where Sgt Alan Close in a 23 Squadron Blenheim (L1458/S) engaged a Heinkel held in searchlights, only to be shot down by return fire. Close was killed but his gunner LAC Laurence Karasek managed to bale out. The Blenheim crashed in flames at Terrington St Clement. A second Blenheim (YP-L), flown by Flt Lt Myles Duke-Woolley (with AC Derek Bell as gunner) was soon in the area and engaged the same Heinkel – 5J+DM of Stab II/KG4:

00:45. Observed a ball of fire, which took to be a Blenheim fighter in flames, break away from behind the tail of the E/A. I climbed to engage this E/A and attacked from below the tail after the searchlights were extinguished. I close to a range of 50 yards and opened fire. E/A returned fire and appeared to throttle back suddenly. My own speed was 130-140mph and I estimate the E/A slowed to 110mph. I delivered five attacks with front guns and during these my air gunner fired seven bursts at various ranges. After the last front gun attack my gunner reported that the E/A’s port engine was on fire. As my starboard engine was now u/s I broke off the engagement and returned to base, where several bullet holes were found in the wings and fuselage, including cannon strikes in the starboard wing and rear fuselage.

One bullet had lodged in Derek Bell’s parachute pack, fortunately without harming him. The Heinkel finally ditched in shallow water in Blakeney Creek on the north Norfolk coast. Coastguards captured the crew, Major Dietrich Fr von Massenbach (the Gruppenkommandeur), Oblt Ulrich Jordan, Obfw Max Leimer and Fw Karl Amberger, who was severely wounded. A subsequent news report revealed:

Two local auxiliary coastguard patrols saw an aircraft in obvious difficulties, off the coast. Flames were issuing from one of its engines, and it crashed in shallow water close to the beach. They gave the alarm and ran to the beach. They intercepted the crew of the aircraft, a Heinkel bomber, as they swam and waded ashore with the help of their rubber dinghy. It seemed at first that the crew, consisting of four men, would show fight. The auxiliary coastguard men thereupon covered the Germans with their firearms. The Germans shouted and surrendered. They were searched and disarmed and detained until the arrival of the military.

By now, other bombers had reached RAF Stradishall, home of Wellingtons, bombs falling around the village of Hargrave, six miles south-west of Bury St Edmunds. The rectory was hit and the vicar’s daughter injured by flying glass. More bombs fell on Lodge Farm, Rede and in Fersfield Street, Bressingham, without causing further casualties. RAF Marham in Norfolk was attacked by a lone bomber, the bombs missing the airfield and exploding near King’s Lynn, while RAF Mildenhall also escaped damage when the intended bombs fell near the village of Culford, four miles north-west of Bury St Edmunds. Bombs also fell near the sugar beet factory – one of the largest in Europe – on the outskirts of the town, slightly injuring two residents of Westfield Cottages in Hollow Road.

In addition to the Blenheims searching for the intruders, which now included aircraft from 604 Squadron, more Spitfires had been scrambled by 19 Squadron. Moments before midnight, a Heinkel released its bombs over Cambridge, where two bombs demolished eight houses in Vicarage Terrace, killing nine persons while another ten were admitted to hospital, three of whom were seriously injured. Among the dead were five children. Bombs also fell at West Fen, Ely, killing one civilian and 30 cattle, and elsewhere in the area. AA guns at RAF Feltwell engaged the raiders but claimed no successes.

Three Heinkels were credited to 29 Squadron’s Blenheims, Plt Off John Barnwell (L6636) engaging one illuminated by searchlights over Debden, which reportedly crashed with its starboard engine on fire. However, Barnwell’s aircraft was hit by return fire and crashed in the sea off the Stour Estuary. He and his gunner Sgt Long were killed. Plt Off Lionel Kells in L1508 fired at another Heinkel and believed that he had shot this down off Felixstowe. This was possibly a 4.Staffel machine that returned damaged by fighters during a sortie to attack Mildenhall airfield. One of Fw Heinz Schäfer’s crew was badly wounded in the stomach and on return was admitted to hospital in Lille. Shortly thereafter, Plt Off Jack Humphries in L1375 damaged another Heinkel near Debden, but his own aircraft was hit by return fire and crash-landed at Debden. His opponent was possibly Fw Erich Gregor’s Stab I machine that belly-landed, badly damaged, on a beach east of Calais on return. Gregor and his crew, Oblt Falk Willis (observer), Fw Karl Brucker and Uffz Josef Jochmann all survived unhurt although their aircraft was written off.

Meanwhile, Flt Lt Sailor Malan in a Spitfire of 74 Squadron encountered a Heinkel, a machine of 4./KG4 in which the Staffelkapitän Hptm Hermann Prochnow was flying. This was probably the aircraft previously engaged by Plt Off Barnwell. Malan pursued it to the coast and finally shot it down to crash into the sea near the Cork Light Vessel moored off Felixstowe. The captain and crew (Obfw Hermann Wojis, Uffz Franz Heyeres and Fw Richard Bunk) were killed and only the Staffelkapitän’s body was recovered. Malan’s subsequent combat report revealed:

During an air raid in the locality of Southend, various E/A were observed and held by searchlights for prolonged periods. On request of [74] Squadron I was allowed to take off with one Spitfire. I climbed towards E/A, which was making for the coast and held in searchlight beams at 8,000 feet. I positioned myself astern and opened fire at 200 yards and closed to 50 yards with one burst. Observed bullets entering E/A and had my windscreen covered in oil. Broke off to the left and immediately below as E/A spiralled out of beam.

The reconnaissance Heinkel – 5J+GA – was then engaged by Flt Lt Malan and crashed at Springfield Road in Chelmsford, ending up in the Bishop of Chelmsford’s garden at 00:30. Oblt Corpus, Obfw Walter Gross and Fw Walter Vick died in the crash, while Ltn Simon had managed to bale out. He was quickly captured. Malan’s report continued:

Climbed to 12,000 feet towards another E/A held by the searchlights on northerly course. Opened fire at 250 yards, taking good care not to overshoot his time. Gave five 2-second bursts and observed bullets entering all over E/A with slight deflection as he was turning to port. E/A emitted heavy smoke and I observed one parachute open very close. E/A went down in spiral dive. Searchlights and I followed him right down until he crashed in flames near Chelmsford.

As I approached target in each case, I flashed succession of dots on downward recognition light before moving into attack. I did not notice AA fire after I had done this. When following second E/A down, I switched on navigation lights for short time to help establish identity. Gave letter of period only once when returning at 3,000 feet from Chelmsford, when one searchlight searched for me. Cine-camera gun in action.

Raiders were reported in the Mildenhall and Honington areas, a salvo exploding a mile from the latter airfield, and, at 01:20, AA guns at RAF Wattisham opened fire while searchlights at Honington illuminated one Heinkel, whose gunner fired down the beams. At about the same time Flg Off John Petre, flying Spitfire L1032 of 19 Squadron, located a bomber near Newmarket. This was 5J+AM of 4./KG4, which then turned and headed towards RAF Honington. Petre opened fire, seeing smoke issue from a damaged engine, but had to sheer off hard to one side to avoid colliding with another aircraft that appeared alongside – a Blenheim – also firing at the Heinkel. At that moment, searchlights illuminated Petre’s Spitfire, allowing the Heinkel’s gunners to return accurate fire. The Spitfire, hit in the fuel tank, burst into flames. Petre was able to bale out but his face and hands were badly burned. On landing he was rushed to hospital in Bury St Edmunds. Meanwhile, his burning Spitfire hit the roof of Thurston House before crashing in its garden.

The Blenheim (K8687/X) was flown by Sqn Ldr Spike O’Brien of 23 Squadron. He opened fire, seeing smoke gushing from the Heinkel’s starboard engine, but had then lost control and went into a spin. The navigator Plt Off Cuthbert King-Clark – actually a qualified pilot flying to gain operational experience – baled out but was killed instantly when hit by a propeller. O’Brien baled out, landing safely, but the gunner Cpl David Little was killed in the crash. O’Brien reported:

Opened fire on E/A with our rear turret gun from below and in front as it was held by searchlights. The E/A turned to port and dived. I gave him several long bursts with the front guns from 50 to 100 yards range and saw clouds of smoke from the target’s starboard engine and a lesser amount from the port engine. I overshot the E/A and passed very close below and in front of him. My rear gunner put a burst into the cockpit at close range and the E/A disappeared in a diving turn, apparently out of control. I suddenly lost control of my own aircraft, which spun violently to the left. Failing to recover from the spin I ordered my crew to abandon the aircraft and I followed the navigator out of the hatch.

Flt Lt Duke-Woolley later related the story as told to him:

In the gunfight the Heinkel went down, then Spike’s Blenheim went out of control in a spin. At that time, popular opinion among pilots was that no pilot had ever got out of a spinning Blenheim alive, because the only way out was through the top sliding hatch and you then fell through one or other of the airscrews! The new boy (King-Clarke) probably didn’t know that but nevertheless he froze and Spike had to get him out. He undid his seat belt, unplugged his oxygen and pushed him up out of the top hatch while holding his parachute ripcord. He told me afterwards that he felt sick when the lad fell through the airscrew. Spike then had to get out himself. He grasped the wireless aerial behind the hatch, pulled himself up by it and then turned round so that his feet were on the side of the fuselage. Then he kicked outwards as hard as he could. He felt what he thought was the tip of an airscrew blade tap him on his helmet earpiece but luck was with him that night.

The damaged Heinkel crashed at Fleam Dyke near Six Mile Bottom in Cambridgeshire at 01:15. Oblt Joachim von Armin, Fw Wilhelm Maier and Fw Karl Hauck were captured, but Uffz Paul Görsch was killed. Flt Lt Duke-Woolley added an amusing sequel to the account:

Spike parachuted down safely to the outskirts of a village and went to the nearest pub to ring Wittering and ask for transport to fetch him home. He bought a pint and sat down to await transport and began chatting idly to another chap in uniform who was in the room when he arrived. After a while, thinking that the chap’s uniform was a bit unusual, Spike asked him if he was a Pole or a Czech. “Oh no” replied his companion in impeccable English, “I’m a German pilot actually. Just been shot down by one of your chaps.” At this point – so the story goes – Spike sprang to his feet and said. “I arrest you in the name of the King. Anyway, where did you learn English?” To which the German [presumably Oblt von Armin] replied, “That’s all right. I won’t try to get away. In fact, I studied for three years at Cambridge, just down the road. My shout, what’s yours?” So that’s just what they did, sat and had a drink.

Flg Off George Ball of 19 Squadron, in Spitfire K9807, was vectored to the Newmarket area to investigate another intruder, finding 5J+FP of 6./KG4 illuminated by searchlights. He pursued this, closing in to 50 yards, seeing his fire entering the Heinkel as it flew southwards, jettisoning its bombs on the way. The Heinkel, flown by Ltn Hans-Jürgen Bachaus, eventually ditched off Sacketts Gap, Margate, at 02:15. Bachaus and two members of his crew Uffz Theodor Kühn and Uffz Fritz Böck were rescued, but Fw Alfred Reitzig had attempted to bale out but his parachute snagged in the tailplane and he was killed.

One of the last claims on this dramatic night was made by AA gunners at Harwich, who believed they shot down into the sea a departing Heinkel at 01:13. This was probably an aircraft from I Gruppe that returned badly damaged by AA fire. There were no crew casualties. The last of the raiders was recorded crossing the coast at 02.50, releasing its bombs in the Clacton area. An empty house in Salisbury Road received a direct hit. Claims were submitted for 10 Heinkels but this was reduced to five and two probables. In fact, six were lost including the one that belly-landed near Calais. Two others returned damaged. Three Blenheims were also lost to return fire, as was one Spitfire. The commander of 5J+AM, Oblt Joachim von Armin, later reflected:

Until the night of our operation no British night fighter operations were reported. There we did not camouflage our aircraft, flew in at 4,500 metres [15,000 feet], and did not anticipate anything but anti-aircraft gunfire from the ground.

Duxford’s station commander Wg Cdr A. B. Woody Woodhall witnessed the action in which 5J+AM was shot down – and shot down its first assailant, the Spitfire of 19 Squadron:

John Petre’s Spitfire burst into flames and he had baled out. I was an eye witness to all this because it occurred over the aerodrome. My immediate concern was for John and after giving instructions for civil police to be alerted to round up the enemy, I sent search parties out. I next learned that John had been picked up suffering from nasty burns and taken to the nearest hospital. After giving orders that the prisoners when captured were to be placed in the guardroom if unhurt, in the sick quarters if injured, I set off in my car to see how John was faring in hospital.

Dawn was just breaking when I returned to Duxford and I was informed that the civil police had collected the prisoners and were bringing them to the guardroom. I left strict orders that there was to be no fraternizing. When the prisoners they were to be given a meal and cigarettes and left in cells until collected by the security people. I was told that there were two German NCOs in the cells, but that the pilot, an officer, had been taken over to the Officers Mess. I found the German pilot taking his ease in the guest room with a cocktail in hand, chatting to Philip Hunter [CO of 264 Squadron] and several of our pilots. Our boys immediately stood up as I came into the room and said ‘Good morning, sir’ but the Hun, an arrogant young Nazi of about 20, remained lounging in his armchair and insolently eyed me up and down, but not for long. I got him to his feet smartly. Needless to say, I had him transferred to the guardroom cell. The boys thought me very hard-hearted and strict. When I told the boys about how badly John Petre was burnt, I think they understood my anger.

The Manchester Guardian reported:

Three German airmen who lost their lives when their bomber was brought down in an Essex town during Tuesday night’s raid were buried in the town’s cemetery yesterday. Full military honours were paid by officers and men of the RAF and a firing party fired three volleys over the one large grave in which the three coffins covered with Nazi flags were interred. The Bishop of Chelmsford officiated. The Bishop’s wife was one of the mourners. There was a wreath from the RAF and another from girl telephonists of the AFS stationed in the town inscribed ‘When duty calls all must obey.’

At the end of the month Marshall Göring issued a general order regarding the air war against Great Britain. In it he stated:

The Luftwaffe War Command in the fight against England makes it necessary to co-ordinate as closely as possible, with respect to time and targets, the attacks of Luftflotten 2, 3 and 5. Distribution of the duties to the Luftflotten will, therefore, in general be tied to firm targets and firm dates of attack so that not only can the most effective results on important targets be achieved but the well-developed defence forces of the enemy can be split and be faced with the maximum forms of attack.

After the original disposition of the forces has been carried out in its new operational areas, that is after making sure of adequate anti-aircraft and fighter defence, adequate provisioning and an absolutely trouble-free chain of command, then a planned offensive against selected targets can be put in motion to fit in with the overall requirements of the commanders-in-chief of the Luftwaffe.

To save us time as well as ensuring that the forces concerned are ready:

(A) The war against England is to be restricted to destructive attacks against industry and air force targets which have weak defensive forces. These attacks under suitable weather conditions, which should allow for surprise, can be carried out individually or in groups by day. The most thorough study of the target and its surrounding area from the map and the parts of the target concerned, that is the vital parts of the target, is a pre-requisite for success. It is also stressed that every effort should be made to avoid unnecessary loss of life amongst the civil population.

(B) By means of reconnaissance and the engagement of units of smaller size it should be possible to draw out smaller enemy formations and by this means to ascertain the strength and grouping of the enemy defences. The engagement of the Luftwaffe after the initial attacks have been carried out and after all forces are completely battle-worthy has for its objectives:

(C) By attacking the enemy air force, its ground organisations, and its own industry to provide the necessary conditions for a satisfactory overall war against enemy imports, provisions and defence economy, and at the same time provide necessary protection for those territories occupied by ourselves.

(D) By attacking importing harbours and their installations, importing transports and warships to destroy the English system of replenishment. Both tasks must be carried out separately, but must be carried out in co-ordination one with another.

As long as the enemy air force is not defeated the prime requirement for the air force on every possible opportunity by day or by night, in the air or on the ground, without consideration of other tasks.