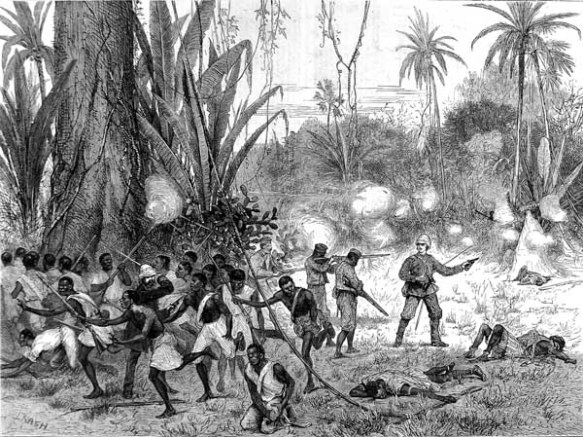

A bush fight, third Anglo-Ashanti war. The Graphic 1874.

The 1900 Ashanti Rebellion was the culminating war between the British and the Ashanti over land and control of Ghana’s coastal region. This rebellion, which was led by Yaa Asantewa, the queen mother of Edweso, had a long and sustained history whose roots can be traced back to the early nineteenth century. At that time, most of the Gold Coast’s fortresses were under British control. British territorial reign included the area where the Ashanti (who form part of the Twi-speaking people of the Akan in present-day Ghana) lived and enjoyed relatively peaceful relations with the Dutch in the central part of the country, some 186 miles (300 kilometers) from the coast.

The Ashanti Confederacy, which was a major state from 1570 to 1900, was ruled under paramount chiefs called Asanthenes. These chiefs supervised an area abundantly rich in gold deposits. Besides the trade in gold, the Ashanti participated in slave trafficking. The Ashanti captured human chattel, whom they obtained from neighboring nations either through raids or through bartering and then sold to European slave traders. Because the Ashanti focused principally on the selling of slaves, they neglected other enterprises such as agricultural production and cloth manufacturing. Then, with the banning of slave trading in the 1850s, which the Ashanti did independently of the British and other European powers, the Ashanti further weakened their economy because they no longer had their main revenue generator, slaves, to sustain their state’s economic growth. The Ashanti’s prominence and stature in the region similarly declined. The Ashanti’s weakened state captured the attention of their former European allies, the British, who viewed the Ashanti’s vulnerability as an opportunity to further their own geopolitical aims. These aims included controlling the land that the Ashanti inhabited and creating a European colony over the entire coastal region.

The Ashanti were one of the few African nations that offered the British serious and recalcitrant resistance. British presence presented a geopolitical problem for the Ashanti, who viewed the intrusion of colonial forces as an infringement upon their sovereign rights and therefore wanted to expel the British from their territory. In 1826 the Ashanti Army launched an offensive attack against the British along the coast. During this encounter the Ashanti suffered major casualties and had to retreat from the coastal plains near Accra because the superior firepower of the British and the Danish had militarily overwhelmed them. With the Ashanti defeated and the Europeans having a tactical advantage, the two warring factions signed a peace treaty in 1831. That treaty did not end the Ashanti’s woes.

The British were relentless in their pursuit of pacifying the entire central area as they signed a political agreement, referred to as the Bond of 1844, with a confederation of Fante states. That agreement not only extended protection to the signatory states but also allowed the British to have authority over them. With Britain purchasing all the territory once owned by Denmark and the Netherlands, it became the sole European country exercising influence over the indigenous people. The Ashanti, who felt further threatened by Britain’s systematic consolidation of power and territorial ownership, launched an invasion in 1873. The British responded by dispatching an expeditionary force to the Ashanti territory, where they captured the capital, Kumasi, and then razed the villages and administrative center. Fearing further retribution, the Ashanti retreated.

That short-lived invasion led to the Ashanti signing yet another treaty with the British. The treaty’s stipulations were as follows. The Ashanti agreed to recognize British sovereignty over the entire coastal region, to pay war reparation costs, and to renounce authority over all territories that resided under British protection. In return, the Ashanti received Britain’s pledge about the coastal area. Following this treaty, the British immediately proclaimed the coastal territories as the Gold Coast Colony and then moved their administrative headquarters from the Cape Coast to Accra.

In the subsequent years, tension between the Ashanti and the British mounted. The Ashanti soon lost their autonomy when the British attacked and occupied their territory and then proclaimed it a protectorate. British officials captured several Ashanti elders, including King Premph, and imprisoned and exiled them to the Seychelles, a small island nation situated in the Indian Ocean. The British were not satisfied with this military gain; they wanted to possess the Golden Stool, the supreme symbol of Ashanti prominence and nationhood, and demanded its surrender on March 28, 1900. British officials dispatched Captain C. H. Armitage to find the Golden Stool, bring it back, and place the symbolic artifact under British custody. Visits to several villages produced no results, and when Armitage found the homesteads populated only by children, as the parents were hiding, he bound and beat them. Armitage meted out the same reprisal to the parents when they surfaced from their hideaways. All of these occurrences instigated the 1900 Ashanti rebellion known as the Yaa Asantewaa War for Independence.

Under the leadership of Yaa Asantewaa, who served as the military tactician and spiritual guide, the Ashanti held a meeting to galvanize the army and prepare for war. Yaa Asantewaa motivated the army with these inspiring and provocative words: “Is it true that the bravery of the Ashanti is no more? If you men of Ashanti will not go forward, then we will. We the women will. I shall call upon my fellow women. We will fight the white men. We will fight till the last of us falls in the battle fields.”

With this call to arms, the Ashanti, who used musketeers, bowmen, and spearmen, laid siege to the British mission at the fort of Kumasi, where the British governor and his entourage took refuge. The Ashanti occupied the fort for three months. The British responded by sending 1,400 troops and additional artillery to quell the rebellion. When the revolt ended in 1901, the British captured and exiled Yaa Asantewaa and 15 of her closest advisers. The last Ashanti rebellion resulted in the formal annexation of the Ashanti empire as a British possession on January 1, 1902.

Ashanti Wars

The brief conflicts known as the Ashanti Wars (1873-1874, 1895, 1900) were the result of British commercial involvement in the tribal affairs of the Gold Coast in West Africa. The wars resulted in the subjugation of the Ashanti Kingdom to the British Empire.

The British were primarily interested in maintaining open trade routes, a goal complicated by the rivalry that existed between the coastal Fante and the more powerful Ashanti inland. The basic British policy involved dealing with the Fante directly and signing a series of (rapidly ignored) treaties with the Ashanti. In 1871 the Fante tried to form a coastal confederation to unite their clans against the Ashanti. Despite a quick and decisive British rejection of the idea, as the effort was seen as an attack on British control of the area, the move provoked an Ashanti offensive on the coast to smash Fante pretensions to power in 1873. If the British had been unwilling to allow the Fante to govern themselves, they certainly were not going to allow the Ashanti to do so.

A British force of 2,500 men under the command of Major General Sir Garnet Wolseley was dispatched to the Gold Coast. His British regulars formed the core of a column that marched inland to the Ashanti capital of Kumasi. Early in April 1874, Wolseley sacked and burned Kumasi and forced the Ashanti to accept a treaty renouncing all claims of coastal authority. They were also forced to pay a large fine in gold dust, pledge to keep the roads to the interior open, and promise to give up the practice of human sacrifice.

Despite the decisive defeat, the Ashanti remained troublesome to the British. During the 1880s and 1890s, the Ashanti showed signs of planning a move against the coastal clans again, prompting a British accusation that they had broken the provisions of the treaty imposed in 1874. British authorities demanded that the kingdom accept status as a British protectorate in 1895; when the demand was ignored, British forces again marched on Kumasi, installing a resident at bayonet point and exiling the royal family to the Seychelles. Five years later the governor demanded that the Ashanti surrender the Golden Stool, the symbol of their sovereignty, provoking a final Anglo-Ashanti war. The kingdom was annexed in the aftermath as a Crown colony.

Bibliography Allman, Jean. I Will Not Eat Stone: A Women’s History of Colonial Asante. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2000. Bleeker, Sonia. The Ashanti of Ghana. New York: William Morrow, 1966. James, Lawrence. The Savage Wars: British Campaigns in Africa, 1870-1920. New York: St. Martin’s, 1985. Chandler, David, and Ian Beckett, eds. The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994. Hatch, John. The History of Britain in Africa. New York: Praeger, 1969. Smith, Melvin C. “Ashanti Wars.” In Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia, edited by Melvin E. Page. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2003