The RAF had always been keen to try to modernise their bomber force through the 1920s, despite budget cuts and the more popular view that bombers were a doomsday weapon and should be banned. However, for the purpose of policing the Empire, they did not require a vast array of heavy bombers. The Hawker Hart, first introduced into service in February 1930, was a light bomber with a load of 500-lb that could be carried 430 miles, with a top speed of 185 mph—faster than the Bristol Bulldog, the RAF’s brand-new fighter. The Hart was the pinnacle of biplane bomber design, and was more than adequate for the purpose of subduing rebellions in the mandates and far-flung quarters of the Empire, and even for a limited conflict with one of Britain’s neighbours, but it could not carry out the knockout blow that Douhet had espoused.

As the continental power battles began, there were moves to improve the range and firepower of Britain’s aerial arsenal for national security. It was hoped that owning a large bomber fleet would be enough to perturb any other power from attacking and, as RAF planners were keen to point out to Government paymasters, it was cheaper to maintain than a warship. A bomber fleet had the ability to attack the enemy further than her coastline, bringing, if the theorists were correct, an end to war quickly and cheaply.

The RAF began to put out specifications for newer larger designs, and began to bring in aircraft like the Vickers Wellesley and Bristol Bombay, but there was always a move for a bigger bomber with a longer range. In 1932, the RAF released specification B9/32 calling for a twin-engined medium bomber for daylight operations, which had to be markedly better than its predecessors. It was a specification that attracted a lot of attention with Bristol, Gloster, Handley Page, and Vickers all keen to get the lucrative contract.

The Bristol Type 131 was designed by Frank Barnwell and was a monoplane powered by two Pegasus engines, while the Gloster B9/32, designed by Henry Folland, was powered by two Perseus VI engines with a loaded weight of 12,800 lb and a 70-foot wing span. Neither design was taken forward; instead the RAF chose the Handley Page HP.52, designed by the German Chief engineer Dr Gustav Lachmann. Lachmann drew on several aspects of the previous HP.47 design, including a fuselage that tapered into a thin boom, giving two perfect gunnery positions above and below the tapering edges. To reduce drag, the fuselage width was shortened to three feet wide, which gave enough room for one man to sit in the pilot seat with a great forward view, but meant that there could only be one pilot. Lachmann’s speciality of slotted flaps and wing slots gave the Hampden a versatile speed of 263 mph when fitted with two 820 hp Pegasus XX engines.

The prototype HP.52, painted green with the registration K4240, flew for the first time on 22 June 1936 from Radlett with Major Cordes, Handley Page’s chief test pilot, at the controls. It was powered by the two Pegasus engines, although there was a brief redesign due to the Air Ministry’s dalliance with Rolls-Royce Goshawk engines. The Goshawk had been an evolutionary step from the old Kestrel IV, and used an experimental method of cooling the engine by using heat transference to turn the coolant to steam, and then condensing it in wing-mounted condensers and generating 700 hp. On evaluation, the RAF grew concerned about the condensers taking up a lot of space, with their weight and position causing quite serious drag on the aircraft. More pointedly was their vulnerability to enemy fire in the wings: a small amount of stray fire might cause serious damage to the aircraft. There were other issues such as coolant leaks and pumping issues, which demonstrated that the whole system was far too complicated for a warplane, and the project was quietly shelved in favour of the more conventional Pegasus engines, with the specification changed again to reflect the dropping of the Goshawk.

The Air Ministry was so impressed by the design that they ordered 180 machines and put it on display at the ‘New Types’ Park at Hendon. A further order for 100 Hampden airframes powered by Napier Dagger engines was issued and given to Short and Harland of Belfast. L7271 was the first of the Dagger-powered Hampdens (later rechristened as Herefords), and was first flown on 1 July 1937. It featured several modifications by Handley Page engineer George Volkert, including the rear turrets being rounded off, the pilot tube moving to below the fuselage, and redesigning the nose section. The Dagger proved an unreliable engine and far from effective, producing far too much noise and wearing out, with problems due to cooling and maintenance issues. Ultimately, the Herefords were either converted to Hampdens or assigned to training duties, leaving the Hampden as the combat variant. The L4034 became the base model for the production run, flying for the first time on 24 June 1938, and later became the first to enter service, in 49 Squadron.

The Hampden was found to exceed expectations, with greater speed and better manoeuvrability than its predecessors and higher pilot seating, which gave a greater visibility and allowed pilots to make steep turns. The controls required the pilot to be familiarised with the comprehensive layout and included the bomb release switches, but once one was acclimatised, it was considered a good aircraft to fly. For defence, the Hampden mounted individual Vickers ‘K’ machine guns in the manual turrets, which were comparable to the emplacements on the Heinkel He 111 and Dornier Do 17Z rather than the heavier—and heavier armed—powerful turrets on the Wellington and Whitley. The Hampden could also carry a bombload of 4,000 lb, which was considerable, especially when compared to the 1,720-mile range and its relatively good top speed of 265 mph. The German Junkers Ju 88 flew for the first time on 21 December 1936, and the V5 prototype set a top speed record of 320 mph while carrying 4,410 lb on a course in March 1939, with the top speed dropping to 280 mph after modification with a range of some 1,429 miles. When you compare the two aircraft on paper, they are broadly similar.

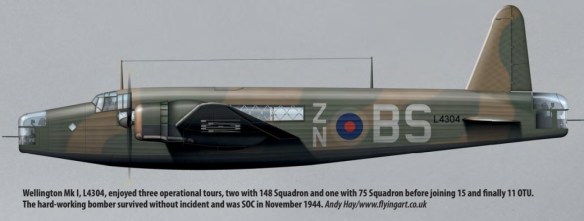

The Vickers submission to B9/32 was what would become the reliable Wellington with Vickers initial internal manufacturing specification being for an airframe that could carry 1,000 lb of bombs 720 miles and possess a range of 1,500 miles. Initial designs were for a high-wing, fixed undercarriage aircraft with Goshawk engines—as per the RAF’s original specification—or Mercury VIS2s. By October 1933, the whole layout was altered, with the wings situated in the mid-wing position and a retractable undercarriage, and the fuselage reinforced by Barnes Wallace’s geodetic system and powered by two Goshawk engines. The geodetic skeleton was ready for implementation into airframes from the autumn of 1933 and was a great step forward in airframe design. The skeleton was fashioned from spirally crossing load-bearing members made from the light alloy duralumin in a similar shape that the R-100 airship had had, as well as Vickers’ other aircraft, the Wellesley. The biggest asset was that the airframe could take a massive amount of damage, with the beams on the opposite side of the fuselage being able to take the load if a hole was blown in the opposite side—this ultimately saved many lives in wartime, with aircraft that otherwise would have crashed in enemy territory bringing their crews home and alive. The aircraft’s doped linen skin was held to the frame by wooden batons.

The new proposal was accepted by the RAF, who requested a prototype for further evaluation, and the type 271 went into production in 1934, only to suffer a major revision when the Goshawks fell through as a practical engine design. K4049 was refitted with a pair of Pegasus X engines and made her maiden flight on 15 June 1936, flown by Captain Joseph Summers, the chief test pilot, and Barnes Wallace.

The RAF were exceptionally pleased with the Vickers design with its range of 2,000 miles and bombload of 4,500 lb. Specification 29/36 was issued on 29 January 1937, formally ordering 180 of the provisionally named ‘Crecies’— the name was changed to Wellington after a protestation from the Air Ministry. K4049 was lost that April when the elevator’s horn balance failure caused it to lose altitude and crash, killing one aboard and causing the production variant to have the horn balance removed.

The first production model, L4212, flew on 23 December 1937. It demonstrated several redesigns, including a deepening of the rear of the fuselage, a new retractable tail wheel, and a fuselage revision that doubled the bombload. The crew was increased by one and the elongated hull was lit by side windows. The production variant was found to be nose-heavy when diving due to the redesigned elevators, and so the engineers modified the flaps and elevator trim tabs. Vickers’ turrets were mounted on the nose and tail, with a pair of guns mounted in the latter while a retractable Nash and Thompson turret was fitted to the ventral position; the Mk I engines were also changed to the 1,000-hp Pegasus XVIII. The first Wellington Mk I was issued to 9 Squadron in February 1939.

The Mk IA saw the crew brought up to six and armament increased to six 303 machine guns (two to each turret), while the Mk IC was a variant that saw the ventral turret supplanted by a pair of Vickers ‘K’ guns that fired out of either side of the fuselage.

The Wellington bomber was seen as the best choice for an unescorted long-range bomber, with the ability to absorb fire from enemy ground emplacements while maintaining a good rate of defensive fire that could deter enemy fighters from getting close to them.

The Bristol Blenheim was to come to be the most ubiquitous British bomber across all of the theatres in the early stages of the Second World War. It was born out of a challenge by the newspaper baron Lord Rothermere, who wanted to see if the aviation industry could create a new fast transport that could carry six passengers, in answer to German designers working on aircraft like the Heinkel He 70.

Bristol had been working on a twin-engined monoplane designed around the Bristol Aquila engine since July 1933, under the designation 135. When Rothermere enquired after the design, the chief engineer, Frank Barnwell, quoted that the proposed top speed was 240 mph at 6,500 feet, prompting the Daily Mail’s owner to order one of the aircraft from the drawing board. Significant changes were made, including switching the engines to Bristol’s Mercury engines, and the new plane was designated as Type 142. The first model, named Britain First, was test flown on 12 April 1935 at Filton in South Gloucestershire—to everyone’s surprise, the aircraft was found to be faster than the biplane fighters of the RAF, with a staggering top speed of 307 mph. Within two months, the Air Ministry had taken a keen interest in the airframe as a potential bomber, with the hope that it could outrun any enemy fighter aircraft, deliver its payload, and then leave the enemy behind on its return leg. On 9 July, talks were convened with Bristol to discuss the suitability of converting the design to make the more militarily suitable 145M, which would require the moving of the low wing to a mid-wing position to create more crew and payload space within the fuselage. The discussion turned to armament, including the obvious provision of a bomb aimer and the need for a Browning machine gun in the nose and a retractable turret in the rear of the fuselage. Specification B.28/35 was released specifically for it and the Blenheim was born. Within three months, the RAF placed a contract for 150 aircraft straight from the drawing board due to the need for rapid expansion and more modern equipment.

The aircraft’s Mercury engines were air-cooled and generated 860 hp; they were also equipped with manual and modern electric starting motors with the labour-saving split-segment engine mounts. This meant that maintenance crews could replace the engine quickly without damaging or moving the carburettors.