The Soviet Union was one of the first countries to realize the unique potential of parachute forces. As early as 1927 there were reports of parachute troops being used against bandits in Central Asia. Within the next two to three years Leonid G. Minov began to organize the first military parachute units. He traveled to the United States to study parachute strategy and techniques employed in air rescue missions. He returned to his country with a supply of American-made Irvin parachutes. In April 1930, Soviet industry produced its first run of domestic parachutes, not surprisingly patterned on the Irvin style.

In a parallel development, General Mikhail Tukhachevski, commander of the Leningrad Military District, began theorizing about and earnestly exploring the plausibility of using airborne troops. Tukhachevski was one of a group of farsighted Soviet military officers who developed the concept of deep battle. This military concept seemed ready made for the employment of parachute troops.

The earliest Soviet involvement with parachute operations went through several phases of development. This was especially true with air delivery techniques. As with many novel developments in military planning, airborne troop theory outpaced the practical aspects of plane design and implementation. The first paratroopers exited their transport plane by climbing through a hole in the top of the fuselage. They then had to crawl along the spine before making their way out along a wing. From the wing the paratroopers rolled off and deployed their parachutes using a rip-cord system. Later Soviet plane designers added small compartments that were constructed under each wing. Paratroopers were then transported to the target areas and dropped like bombs over their drop zones. Still later, Minov switched from the ripcord method of opening parachutes to the static line concept. This method consisted of hooking deployment lines attached to the backpack of the parachute to a fixed cable inside the airplane. The act of jumping out of the plane stretched the static line to its maximum length and the falling paratrooper’s body pulled the parachute pack opening tie loose, thus deploying the parachute.

Stalin’s military purges of the late 1930s robbed the Red Army of its top leadership. The parachute force was especially hard hit and lost virtually all of its leadership down to about the rank of major. Included in the first round of purges was Tukhachevski himself. Despite the severe impact of the purges, experimentation with unit size or mission types continued. Parallel studies were conducted as to methods of transport and coordination with other units in the Army. By June 1941 there were five airborne corps in the Red Army, each consisting of about 10,000 troopers. These corps had been built from the cadres of the five Airborne Brigades (the 201st, 204th, 211th, 212th, and 214th). These brigades had been the standard unit until changes were initiated sometime in 1940. The corps consisted of three airborne brigades, each composed of four battalions of 678 men each. The organization of airborne forces looked like this:

1st Airborne Corps(Kiev Military District)

1st, 204th, and 211th Brigades

2nd Airborne Corps(Kharkov Military District)

2nd, 3rd, and 4th Brigades

3rd Airborne Corps(Odessa Military District)

5th, 6th, and 212th Brigades

4th Airborne Corps(Western Special Military District)

7th, 8th, and 214th Brigades

5th Airborne Corps(Baltic Special Military District)

9th, 10th, and 201st Brigades

202nd Brigade(Far Eastern Military District)

The most immediate problem faced by the Soviets, which was problematic to most of the countries that employed parachute forces, was the lack of transport aircraft. Soviet production of transports had to be cut in order to satisfy a more pressing need for fighters and bombers. Among the few transport crews available most had no experience in formation flying, night navigation, or combat operations. To complicate things even more, the Lutfwaffe had maintained complete dominance in the air since the German invasion in June 1941. This air superiority severely restricted the use of Soviet airborne troops in their original capacity.

The Soviets were now confronted with the necessity of employing the deep battle concept. Soviet parachute forces, or “Locust Warriors” as they were called, were now deployed on missions that required them to link up with local partisan units in the areas where they were active. The paratroopers then became responsible for supplying, training, and leading these partisans in combat operations. All these operations were coordinated within the framework of larger army battle strategy or front missions.

Soviet airborne forces were first employed on a major scale during the defense of Moscow. In the early winter of 1941, the German Fourth Army and Fourth Panzer Army ground to a virtual halt just 25 miles from Moscow. Facing the Germans were the Russian Tenth and Thirty-third Armies. German forward advances were thwarted and the battle lines became stabilized just east of the area that included Vyazma and Yukhnov. The supply trucks, on which the Germans relied heavily, had to pass through these towns. To arrive at their forward positions, these German convoys had to pass several pockets of partisan activity. These partisan forces began to grow more active. Soon they were conducting raids to interdict supply routes in the areas west and south of Vyazma and in the area of Yukhnov.

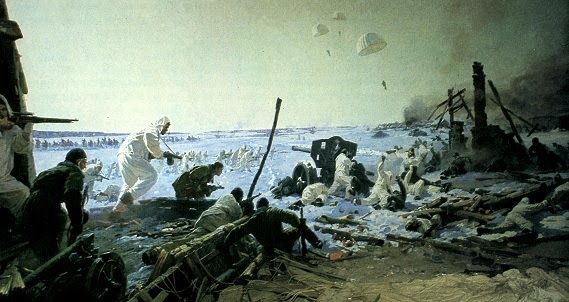

In order to assist a counterattack forming on its left wing, the Red Army’s West Front (Army Group) ordered an airborne assault to seize key air, road, and rail transport facilities. The goal was to block any further movement of German supplies, equipment, and reserves from reaching the front. For the next two months, the Soviets began conducting airborne assaults. These were conducted mostly at night and against targets along both supply routes. Most of the airborne units involved belonged to 4th Airborne Corps. Original plans called for the entire corps to be dropped but combat developments, as they so often do, forced a change in these plans. One of these developments was weather. By early January 1942 the temperature had dropped to minus 44 degrees in the area around Vyazma.

On the evening of 2/3 January 1942, the airborne phase began when 348 men of the 1st Battalion, 201st Airborne Brigade, under the command of Captain I.A. Surzhik jumped in the vicinity of the airfield at Myatlevo. This was east of Yukhnov and along the southern supply route. The airborne unit’s mission was to clear and secure the airfield for the air-landing of the 250th Rifle Regiment. In addition, the battalion was to capture and hold the bridge over the Shanya River. Surzhik’s battalion landed successfully but then the weather quickly worsened. The next two days were spent clearing snow from the airfield while also repulsing several counterattacks by the Germans.

Eventually the Soviet high command decided not to send in the 250th. The parachute battalion was ordered to begin independent activities. For the next two weeks the battalion conducted several guerrilla-style raids, overrunning several German garrisons near Gribovo and Maslovo. Since holding the Shanya River bridge was now implausible, Surzhik and his men blew it before infiltrating back to their lines.

On the night of 3/4 January, the remnants of an improvised airborne detachment under the command of Captain I.G. Starchak was deployed. This unit, originally composed of 415 men plus 50 men from 214th Airborne Brigade, had been used in a combat jump to the northwest of Moscow in December. The current plan called for Starchak’s men to jump near the Bolshoye Fatyanova airfield. The transport, however, dropped the paratroopers over a widely scattered area due mainly to heavy German antiaircraft fire. In fact, six of the planes returned to their airfields without having dropped their paratroopers. On the evening of 7/8 January, Starchak and his unit seized the Myatlevo train station and blew up all the rolling stock to be found in the vicinity. By 20 January, Starchak was wounded and had only 87 men left under his command. Remnants of his unit finally were able to join up with elements of advancing army units near Nikolskoya.

In the early morning hours of 18 January, 1/201st and part of 2/201st Airborne Brigade jumped into a scattered area between Znamenka airfield and the village of Zhelanke. This area was about halfway between Vyazma and Yukhnov. Their mission was to seize and secure this airfield for a follow-on air-land operation that was to bring a rifle regiment into the field. The units were then to move south to Yukhnov and cut off the supply route. This action was designed to support the advance of the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps against Myatlevo. The jump operation was unopposed. Surzhik’s unit formed up first and attacked a German unit at the airfield. The Germans, however, held. Rather than suffer further casualties in an attempt to capture the airfield, Surzhik and his men created an improvised airstrip near the village of Plesnovo and radioed that they were ready to receive the air-land elements. Immediately, the remaining 200 men of 2/201st air-landed, accompanied by the control group for the overall operation. Between 20 and 22 January, the 250th Rifle Regiment also landed in force.

The Germans, noting the volume of nighttime air activity, became concerned about a railroad bridge on the Ugra River, south of Vyazma. Virtually all of their important supply trains, running south, had to use this bridge and to have it captured or destroyed would seriously interrupt this logistical flow. Therefore, four rifle companies were dispatched to secure the bridge. Their movement was essentially lateral traffic behind the German front. However, when the Germans arrived on 1 February they were immediately attacked by Surzhik’s battalion. Although they could not destroy this enemy threat, the Soviets had the Germans surrounded and railroad traffic was effectively stopped.

According to plan, 2/201st and most of the 250th Rifle Regiment units fought their way south toward Yukhnov and the supply route. The rest of the Soviet forces remained at the airfield to block the north-south road between Vyazma and Yukhnov. On 25 January, 1st Guards Cavalry Corps broke through the German lines, crossed the southern supply route, and continued north to link up with the airborne units.

Between 27 January and 4 February 1942, the three brigades of 4th Airborne Corps (7th, 8th, and 214th) were dropped piecemeal in the general vicinity of Vyazma. They landed along the northern supply route with the mission to cut the northern rollbhan that ran from Smolensk through Vyazma. Most of the drops were not very concentrated due to the inexperience of the Soviet transport pilots. During the day Luftwaffe bombers attacked airfields that were being used to drop and resupply the paratroopers. By night, the airfields were repaired and put back into use. Bad weather finally put a stop to all air operations.

On 3 February, the Soviet Thirty-third Army drove a wedge five miles deep between the two German armies. The Germans quickly regrouped, cutting this salient and sealing it off. A five-division corps was then assigned the mission of reducing this pocket and clearing the parachutists who were threatening Vyazma and the northern supply route. Despite horrid weather, some of the pockets had been eliminated and supplies were rolling into Vyazma on a regular basis by mid-month.

From 17 to 23 February, more Soviet paratroopers (2/8th Airborne Brigade, 4/204th Airborne Brigade, and all of 9th and 214th Airborne Brigades) had jumped into the general areas of Staritsa, Monchalova, Okorokova, and Zhelanye. Of the 7,373 dropped, some 5,000 paratroopers managed to quickly assemble and continued on their mission to attack toward Yukhnov. Once the drops had been completed the units moved quickly. The recently arrived airborne units linked up with the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps and the remnants of the airborne units that had parachuted in earlier. Another attack against the southern supply route was launched. The road was cut and held by the Soviets for two days. A strong German counterattack again reopened the road.

The Red Army paratroopers maintained heavy pressure on the Germans and forced them to withdraw from Yukhnov on 3 March. On 6 March, the Russian airborne and cavalry units drove to within four kilometers of the southern supply route before being stopped. At the same time, a parachute battalion of 450 men jumped near Yelnya, farther to the west. A link-up with local partisans was effected. The combined force attacked and seized a supply base in the railroad center at Yelnya. They also succeeded in surrounding the fairly small German garrison in this area.

On 7 March, another German front line corps, the XLIII, was taken off the line and committed against the Soviet cavalry, airborne, and partisan forces operating in their rear. By 19 March, the Soviets were slowly, but steadily, driven into the forests around Lugi. A reinforced German company was also sent to relieve the besieged units at the Ugra River railroad bridge, but this effort failed. Then, beginning 25 March and lasting for one month, the two German armies (the Fourth and Fourth Panzer) coordinated a strong, slugging, give-no-quarter attack against the encircled Soviet units.

On 19 April, 4/23rd Airborne Brigade of the 10th Airborne Corps jumped into the area around Svintsovo. They were to reinforce what was left of the 4th Airborne Corps, which was now down to about 2,000 effectives with perhaps another 2,000 sick or wounded. By 23 May, the corps strength was 1,565 with 470 sick and wounded. A final effort to reinforce the remaining paratroopers was launched between 29 May and 3 June. The remaining battalions of 23rd Airborne Brigade and 211th Airborne Brigade were dropped into the western end of the pocket at Dorogobuzh. But this effort was mostly to no avail.

On 25 April, the Thirty-third Army surrendered. The Germans spent May and June systematically destroying the remaining airborne and cavalry units still operating in the area. It was only during this final drive against the paratroopers in Yelnya and those that had surrounded the Ugra River bridge, that the Germans could boast of finally defeating this enemy.

The German commanders who survived the war tended to minimize the role of the Soviet airborne in this battle. This was not, however, the prevailing opinion at the time of the fighting. The Germans then had admitted that the presence of the Soviet parachute units in their rear area was the chief cause of their withdrawal from Yukhnov in March. One German unit claimed the paratroopers were the very best of the Soviet infantry.

#

As with the Allied Market-Garden operation in 1944, military writers are split on the issue of whether using Soviet airborne units in the Vyazma-Yukhnov battles was successful. The mixed opinion regarding this subject is precisely because this military action was more a campaign than an operation. It was part of a mighty struggle to drive the Germans away from Moscow. From the Soviet perspective, this fighting in the Vyazma-Yukhnov area was an overwhelming victory in the defense of Moscow.

This campaign was justified by a political decision based almost entirely on desperation. It required that the Soviet high command use all of the capabilities at its disposal. Because it was required, the high command then employed conventional infantry, at least two corps of cavalry, and as much of its parachute forces as could be conceivably jammed into the battlefield.

To highlight this sense of desperation, there have been stories recounting the fact that the Soviets dropped paratroopers into the snow without parachutes. This is in fact known to have happened on at least two occasions. The first was in Finland. The second was during the Vyazma operation. In both cases the planes were flying low and slow, and the drops were made into deep snow drifts. In the Vyazma operation, discussed here, there is even a mention that some of the paratroopers were wrapped in burlap sacks before they were dropped. The mere existence of these stories should point out the utter desperation in which the Soviet high command found itself while defending Moscow. In a desperate situation such as this the necessity of using special operations forces, regardless of the outcome, should not be second guessed.

Employing Vandenbroucke’s criteria, there are negative observations to be made in two areas of the campaign. There was a good deal of wishful thinking on the part of the Soviet high command that the airborne portion would have great success.

The planners, however, seem to have overlooked or disregarded several things. First and foremost, was the general lack of transport aircraft available to bring in airborne forces in strength. Additionally, the pilots of what transports were available had not flown jump operations before. This prevailing negative also applied to many countries in the course of the war. Departure airfields, to be used by the paratroopers, were constantly being changed due to tactical considerations. Granted, not much could be done about this. However, moving the paratroopers from one place to another, on short notice, just delayed their arrival at their targets. Many of the transports that were available in early 1942 were also used to evacuate the wounded, thus causing scheduling nightmares. In the final analysis, wishful thinking or not, the supply routes were bona-fide military targets and the paratroopers were available.

There is at least one indication of inappropriate intervention. Once the operation started the paratroopers were virtually committed to suffer for long periods of time without hope of reinforcement or replacement. Again, however, the desperate nature of this struggle certainly justified this.

Employing the McRaven criteria, only a few problems were to be found and they were in the execution phase. These were problems with the twin issues of security and repetition. These issues only became problems once the operation began. Security was very good until the Germans discovered the presence of the paratroopers. There were only so many places for the paratroopers to be dropped, leading to the repetitious use of the same drop zone. The problem of using the same drop zones, on succeeding nights, was just inviting German initiatives and the paratroopers were hit hard once on the ground. Furthermore, German anti-aircraft units were now on the alert and positioned themselves to score several major victories. The element of speed was lost when the units and/or their drop zones were discovered. Although the fighting was tenacious and prolonged, the Germans usually destroyed the Soviet units in detail—and not just the airborne units.

One negative assessment of this campaign took issue with the fact that while the organization and planning of the parachute assaults were conducted by the staff of the airborne forces, once on the ground the paratroopers fell under the operational control of the army group, which had taken no part in the original planning. This is really petty criticism. Even though the airborne staff planned the operation the Soviet high command could and did change it to meet operational needs. To be truly effective special operations forces must fill a role in the overall theater operations plan. This means that the ground commander, who may indeed not have helped shape the original planning, must still maneuver all the forces available to him to achieve victory. That is, after all, why he is in command—to achieve victory.

In the long run, this campaign was successful. There were local victories in the German rear areas and a German plan to resume the offensive in March had to be discarded because of the imminent threat to their rear area supply routes. The final assessment as to its success lies with the fact that the Germans never again threatened Moscow.

SOURCES

Books:

Beaumont, Roger Α.; Military Elites—special Fighting Units in the Modern World; New York; Bobbs-Merrill; 1974

Galvin, John R.; Air Assault—The Development of Airmobile Warfare; New York; Hawthorn Books; 1969

Glantz, David M.; The Soviet Airborne Experience; Fort Leavenworth; U.S. Army Command and General Staff College; 1984

Gregory, Howard; Parachuting’s Unforgettable Jumps; La Mirada, CA; Howard Gregory Associates; 1974

MacDonald, Charles; Airborne; New York; Ballantine Books; 1970

Reinhardt, Hellmuth et al; Russian Airborne Operations; Historical Division, HQ US-AREUR;1952

Thompson, Leroy; Unfulfilled Promise—The Soviet Airborne Forces 1928—1945; Bennington, VT; Merriam Press; 1988

Tugwell, Maurice; Airborne to Battle—A History of Airborne Warfare 1918-1971; London; William Kimber; 1971

Zaloga, Steven J.; Inside the Blue Berets—A Combat History of Soviet and Russian Airborne Forces, 1930—1995; Novato, CA; Presidio Press; 1995

Articles:

Dontsov, I. and P. Livotov; “Soviet Airborne Tactics”; in Military Review, October 1964

Gately, Matthew J.; “Soviet Airborne Operations in World War II”; in Military Review, January 1967

Reinhardt, Hellmuth; “Encirclement at Yukhnov: A Soviet Airborne Operation in World War II”; in Military Review, May 1963

Turbiville, Graham H.; “Soviet Airborne Troops”; in Military Review, April 1943

————; “Soviet Airborne Forces: Increasingly Powerful Factor in the Equation”; in Army, April 1976