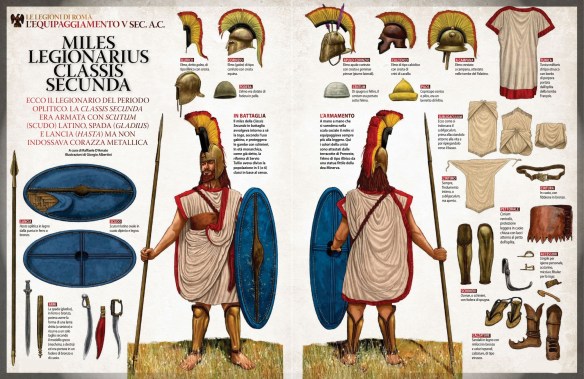

Roman infantry are described by Livy as organised into centuries by class, performing manoeuvres on the battlefield and frequently pressing their officers to provide more aggressive orders rather than charging disobediently. They are therefore classed as regular and the 1st class, equipped as armoured hoplites, as superior. The 2nd and 3rd class had the oval Scutum as their shield instead of the round hoplon or aspis and had only minimal armour. The 4th class are described by Livy as having spear and javelins but no shield, but by Dionyssos as also having shields. Livy describes the 5th class as slingers, Dionysios as slingers and javelinmen.

At the end of the fifth century BC, Rome was still, like the towns around her, emerging from an agricultural society driven by an agrarian economy. Rome was different because she became increasingly larger than her enemies and she was extraordinarily receptive to outside influences – melding the best facets and successful practices from friend and foe alike. Militarily, Rome had a facility for adapting tactically and developing weaponry and armour based on extensive combat experience. Every battle fought, even those she lost, was a lesson in military science for the Romans.

In early summer each year, the army was summoned and trooped out to the latest theatre of war. Every autumn, the army, or what was left of it, was discharged until the call to arms the following year. The armies were usually led by two consuls, or by consular tribunes, or by dictators in times of tumultus, times of dire crisis. These consuls usually operated in concert with each other, not always harmoniously. They often brought no experience in leading an army or prosecuting a campaign. Time spent in the army or navy was simply another rung on the ladder of the cursus honorum, the political career path of the elite Roman. The army, and war, came with the career, and the successful execution of the military element went some way to contributing to longterm glory and success. This, in turn, fostered a belligerent attitude amongst Roman politicians-cum-commanders. Victory in war meant success in politics; success in politics was often dependent on victory on the battlefield.

The lower ranks of the army, the heavily armed infantrymen known as classis, were self-financing and recruited from farmers. Below the classis was the infra classem, skirmishers with less and lighter armour which required a smaller financial outlay. Above the classes were the equites, patricians with some wealth who made up the majority of the cavalry, officers and staff. Their money often came from land ownership. Soldiers were unpaid in the early days, providing their own rations, arms and armour.

War was not kind to the classes. It usually meant that they were away from their lands, forced to neglect their very livelihood for increasingly long stretches of military service. Moreover, they suffered virtual ruin when their farms were depradated by enemy action. The longer they served, the greater the chance of being killed or badly wounded and disabled, rendering them unfit to work on their lands. A ready supply of slaves to work on the lands of the wealthy was fuelled by prisoners of war, reducing the Roman or Italian agricultural worker’s value in the job market to little better than slaves themselves. Military duty plunged some classes into debt and led to virtual bondage to patricians – an ignominious semi-servile arrangement, nexum, which forced a farmer or farm worker to provide labour on the security of his person. Defaulting led to enslavement. Richer landowners could bear losses better as they were the beneficiaries of this bond-debt process, which allowed them to procure yet more land and cheap labour at the expense of the classes and infra classes. In short, the rich just got richer, a process helped also by their favourable share of increasing amounts of booty. Once Rome had conquered the Italian peninsula, the poorer workers could not even be helped out by land distribution; after 170 BC, land distribution stopped altogether. This, of course, led to resentment, which was only assuaged by personal allocations from tribunes and generals. Land allocations overseas were not considered an option until the time of Julius Caesar.

Oakley has tabulated the number of prisoners of war captured and subsequently enslaved by Rome in the nineteen battles between 297 and 293 BC, and recorded in Livy: approximately 70,000. Even allowing for some exaggeration, this clearly illustrates the impact conquest had on the careers and employment prospects of many agricultural workers. It did not stop there, of course: when Agrigentum was captured in 262 BC, no less than 25,000 prisoners were reportedly taken, all swelling the already competitive job market.

Roman warfare was then inseparable from Roman politics and from Roman economics; land questions and the Conflict of the Orders provided a constant soundtrack to the early wars.

The soldier depended on the value of and income from his land for financial clout, the ability to qualify for service and pay for his armour and weapons. The Conflict of the Orders ran from 494 BC to 287 BC and was a 200-year battle fought by the plebeians to win political equality. The secessio plebis was the powerful bargaining tool with which the plebeians effectively brought Rome grinding to a halt and left the patricians and aristocrats to get on with running the city and the economy themselves – the Roman equivalent to a general strike. The first secessio, in 494 BC, saw the plebeians down weapons and withdraw military support during the wars with the Aequi, Sabines and Volsci. That year marked the first real breakthrough between the people and the patricians, when some plebeian debts were cancelled. The patricians yielded more power when the office of Tribune of the Plebeians was created. This was the first government position to be held by the plebeians, and plebeian tribunes were sacrosanct during their time in office.

Servius Tullius, Rome’s sixth king, may have gone some way to militarizing Rome when he divided the population into wealth groups – their rank in the army determined by what weapons and armour they could afford to buy, with the wealthiest serving in the cavalry due in part to the cost of horses. Servius was certainly responsible for changes in the organization of the Roman army: he shifted the emphasis from cavalry to infantry and with it the inevitable modification in battlefield tactics. Before Servius, the army comprised 600 or so horse reinforced by heavily-armed infantry and lightly-armed skirmishers; it was little more than a militia of landowning infantry wielding pilum, shield and sword (gladius), operating like Greek hoplites in phalanx formation. The rest were composed of eighteen centuries of equites and thirty-two centuries of slingers. (A century was made up of ten conturbenia, amounting to eighty or so men.) The Etruscans, and then the Romans, absorbed Greek influences when they adopted full body armour, the hoplite shield and a thrusting spear – essential for phalanx-style close combat warfare.

Men without property, assessed by headcount, capite censi, were not welcome in the army, in much the same way that debtors, convicted criminals, women and slaves were excluded. However, slaves were recruited in exceptional circumstances, notably after the calamitous battle of Cannae and the manpower shortage it caused. Servius also reorganized the army into centuries and formed the parallel political assemblies, reinforcing the inextricable connection between Roman politics and Roman military. His ground-breaking census established who was fit – physically and financially – to serve in the Roman army. Recruitment extended from between age 17 and 46 (iuniores), and between 47 and 60 (seniores), the more elderly constituting a kind of home guard. The lower classes were not required to report with full body armour; this led to the use of the long body shield, the scutum, for protection, instead of the circular hoplite shield.