With the outbreak of the CIVIL WAR (1861-65), many of the frontier regulars were transferred east to fight the Confederates. In the absence of the regulars, states and territories turned to volunteer and militia units to deal with the Indians. Thus, many of the major engagements against the Indians during the Civil War years-including the battles of WOOD LAKE (1862), BEAVER RIVER (1863), WHITESTONE HILL (1863), and SAND CREEK (1864), and the concluding phases of the NAVAJO WAR-were dominated by volunteer rather than regular units.

Around 20,000 Native American soldiers enlisted and mustered into the Union and Confederate armies. Why did they fight, and how did they fare? Here, again, scholars make the argument that Indian experiences both reflected and diverged from those of white soldiers on both sides. Like white soldiers, Indians had many reasons for enlisting. Some did feel a fealty toward the Union or the Confederacy, a shared identity with their white neighbors that brought them into the fight. others wanted to seek out adventures, to prove their manhood and “follow their ancestors’ footsteps into battle” during a time and in a place that did not offer traditional opportunities to do so (Evans 2010: 188-189; Hauptman 1995: xi-xii, 131; Bailey 2006: 39). others did it for the money. A group of Pequots, for example, watched as the Union Navy diverted their whaling boats to use in blockades and naval battles; as the whaling industry ground to a halt, they turned to the Army of the Potomac (where they served in the 31st Colored Infantry) for a steadier paycheck (Hauptman 1995: 145). Most scholars argue that ultimately, Native soldiers enlisted as a way to pursue their own personal or tribal interests, and not out of a sense of duty. They sought to protect their homes and families from marauders of all stripes but most of all – and here is where they diverge from their white counterparts – their service seemed imperative for “their Indian community’s survival.” Laurence Hauptman and Clarissa Confer have been the most aggressive in arguing that Indian soldiers believed that through their enlistment and their bravery in battle, they would gain trust and leverage, which might help them in future negotiations with either the Union or the Confederacy, or both. They fought for the future of their own nations, not for the future of the United States (Hauptman 1995: xii, 37, 133; Confer 2007: 11).

Civil War (1861-1865) bloodiest war in U. S. history, in which Indians participated on both sides For the Indians of the Plains, in the Southwest, and in the Far West, the Civil War’s most noticeable impact was the withdrawal of the regular troops who had formerly garrisoned the army’s frontier posts. The resulting power vacuum pitted Indian groups, anxious to reassert their dominance, against non-Indian state and local volunteer units, just as determined that the Indians should not. Ominously, many of these volunteers had little respect for the niceties of what was then recognized as civilized warfare.

The war years were particularly violent for the Native American peoples of Minnesota and the Dakotas, Colorado and Utah, and New Mexico and Arizona. On the northern plains and prairies, the MINNESOTA UPRISING (1862) resulted in the decimation of the military power of the Santee Dakota (Eastern) SIOUX. To the south, intermittent raiding by Indians and non-Indians also led to several bitter conflicts, including the SHOSHONE WAR (1862-63) and the massacre at SAND CREEK (1864). In the far Southwest, JAMES HENRY CARLETON and CHRISTOPHER “KIT” CARSON conducted cruelly effective campaigns against the APACHE and the NAVAJO (Dineh). But in a very real sense, these conflicts between 1861 and 1865 are indicative, not of the special circumstances of the bitter war between the Union and the Confederacy, but as part of the ongoing struggle between Indians and non-Indians for domination of the American West.

More directly related to the Civil War was the brutal con test for control of the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), home to the nearly 100,000 members of the so-called Five Civilized tribes-the CHEROKEE, CHOCTAW, CHICKA SAW, CREEK, and SEMINOLE. Loyalties cut across ethnic, cultural, and tribal lines. Those who had become more acculturated into non-Indian society, including the majority of mixed-bloods and almost all the slaveowners, tended to support the Confederacy, while traditionalists most often sympathized with the Union. The Chickasaw and Choctaw generally favored the Confederacy, and they supplied the FIRST CHICKASAW AND CHOCTAW REGIMENT to the Southern cause. The Cherokee were bitterly divided. Factions supportive of JOHN ROSS, principal chief of the Cherokee, were sympathetic to the North. Ross’s chief rival, STAND WATIE, led those who supported the Confederacy. The Creek were, if anything, even more deeply divided. Opothleyahola’s faction was strongly pro-Union, but half-brothers Daniel N. and Chilly McIntosh backed the South and would raise a regiment of Creek fighters. Most Seminole attempted to remain neutral, although John Jumper, an ordained minister, would help enlist a number of his people into the McIntosh’s Creek regiment.

In summer 1861, the Confederate government dispatched Brigadier General Albert Pike, a lawyer who had recently won a $140,000 suit for the Creek, to drum up support for the Southern cause in the Indian Territory. Fearing a Confederate victory, the careful Ross agreed to a treaty of alliance with the Richmond government and even agreed to raise another Cherokee regiment. Unionist Creek and Seminole refugees headed north with Opothleyahola, fighting past pro-Confederate forces near the present-day town of Yale on November 19 and again near present-day Tulsa on December 9. On the 26, however, pro-Confederate Indian forces, led by Watie and supplemented by three regiments of Texans, routed the Unionists and drove them in disarray into Kansas.

With the Indian Territory seemingly cleared of the Union threat, in early 1862 Pike led the two Cherokee regiments (totaling about a thousand men) to link up with a Confederate army under EARL VAN DORN. Pike’s men participated in the Confederate defeat at PEA RIDGE (1862); demoralized by their loss and by the South’s failure to supply them, they then withdrew back to Indian Territory. Pike would soon resign, disgusted with the government’s lack of support.

A federal counteroffensive came that summer. Some 6,000 Union troops, including two Indian regiments (one composed of Creek and Seminole and the second recruited from the refugees who had fled to Kansas), pushed into Indian Territory. The Creek distinguished themselves in the Union victory at Locust Grove (July 3); that same day, Stand Watie’s Cherokees were also routed by federal troops. The other Cherokee Confederate regiment soon defected to the Union, and John Ross effectively renounced his alliance with the Richmond government. But campaign momentum shifted with the withdrawal of several federal regiments back to Missouri, and by the end of September the pro-Confederate Indian forces once again controlled the territory.

Early 1863 was marked by raids and counter-raids by the Indians of one side against those of the other. This civil war within the Civil War left much of the once-prosperous Indian Territory destitute. On July 17, Indian regiments on both sides participated in the battle of HONEY SPRINGS a Union victory. The fall of Little Rock to federal forces that September placed even more pressure on the Confederate forces in Indian Territory. In December 1863, a 1,500-man strong Union Indian Brigade, composed of the three loyalist Indian regiments struck deep into Choctaw and Chickasaw lands, inflicting serious property damage and leaving some 250 pro-Confederate Indians dead Watie’s raids into the lands of his pro-Northern Cherokee rivals and against Union supply lines continued nonetheless, earning him a promotion to brigadier general in May 1864. And on September 19, Watie’s new brigade of about 800 Cherokee, Seminole, and Creek, cooperating with a brigade of Texans, captured a 300-wagon enemy train loaded with more than $1.5 million in supplies near Cabin Creek. The spectacular affair was the biggest Confederate victory in the Indian Territory.

Guerrilla warfare along the Arkansas River valley would continue, but affairs elsewhere marked the Confederacy’s death knell. On June 23, 1865, Watie finally surrendered, the last Confederate general of the war to do so. The United States, which held that the prewar treaties had been abrogated, dealt harshly with the tribes that had supported the Confederacy. New treaties agreed to in 1866 required the Five Civilized tribes to make room for several other Indian groups, who were to be removed from Kansas and other areas and relocated to Indian Territory.

Further Reading Josephy, Alvin M., Jr. The Civil War in the American West. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991

Apache Pass (1862)

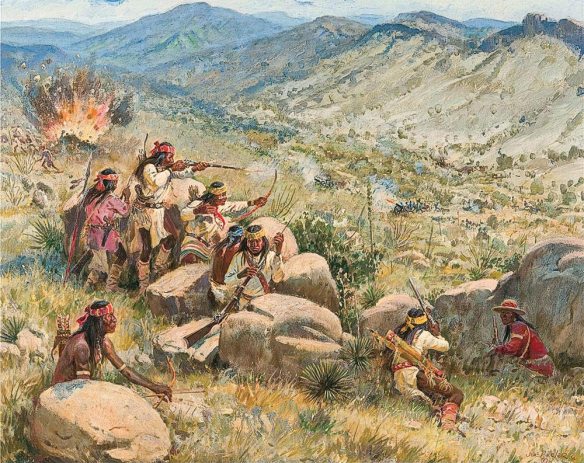

Battle of Apache Pass by Joe Beeler

Apache ambush in southeastern Arizona of the First California Infantry, a state volunteer regiment When the CIVIL WAR (1861-65) erupted, Union soldiers had been manning various posts and forts throughout the Southwest. Soon, many of the soldiers were ordered east to fight, and various posts were abandoned. The APACHE, probably unaware of the Civil War and believing that they were driving the white men out of their territory, stepped up their raids into Mexico and their attacks on white settlements in Arizona and New Mexico. Meanwhile, Confederate troops moved into the Southwest and soon declared a war of extermination against the Indians.

In response to the presence of Confederates in Arizona and New Mexico, and in order to keep the Union transportation lines open to California, a column of Union soldiers led by Colonel JAMES HENRY CARLETON set out westward across southern Arizona. Lieutenant Colonel Edward E. Eyre and 140 men of the First California Cavalry went ahead to reconnoiter. On June 25, 1862, the Union forces encountered Apache near Apache Pass. The Apache, under the protection of a white flag, expressed a desire for friendly relationships. Carleton, hoping to form an alliance with the Apache against the Confederates, sent 122 men from the First California Infantry east from Tucson. Four days later, on July 14, 1862, the soldiers entered Apache Pass. There they were ambushed by the Apache, who attacked the rear of the column and fired from the rocks high above the route. The soldiers, who had marched 40 miles that day without water and were only a half mile from a spring, fought back. The soldiers raised their howitzers and fired into the rocks. The fighting continued for several hours. Before the Indians withdrew, two soldiers were killed and two wounded. Most accounts estimate that the Apache lost about 10 warriors.

The Battle at Apache Pass had a dual significance. First, it brought together various Apache leaders in an alliance against the white soldiers. Present at the battle were COCHISE and MANGAS COLORADAS, who mastermined the affair, as well as VICTORIO and the young GERONIMO. Second, as a result of the battle, Carleton argued that a post had to be built to guard the Apache Pass and to protect the spring. Fort Bowie was built, and it became one of the most important forts during the APACHE WARS (1861-86).